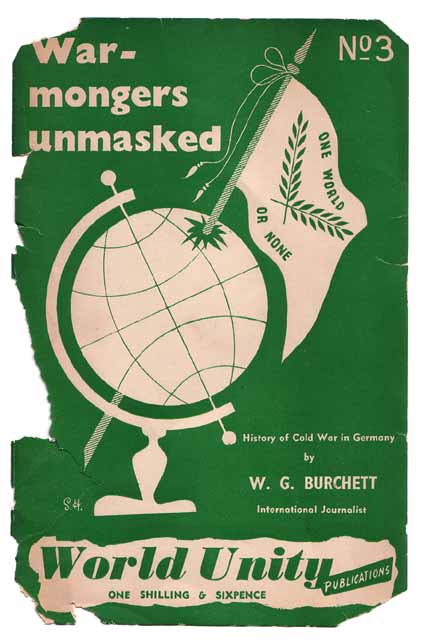

Warmongers Unmasked: History of Cold War in Germany, Wilfred Burchett. 1950

In early June, 1947, in the company of Denis Weaver of the News-Chronicle and Eric Bourne of Reuters, I paid a visit to Mecklenberg and Pomerania. The prime object of our trip was to see Peenemunde, the research station for German secret weapons and the testing ground for the V1s and V2s. For me, however, the greatest attraction of the trip was to study again Soviet agricultural methods at close hand.

The Peenemunde story itself, however, is worth recounting again. There were almost daily references at that time in the British and American press to Peenemunde, references that were, of course, splashed in the western, German press. There were stories from Sweden of streaks of fire searing the sky at night, of mysterious explosions, rockets skimming across the skies and coasts of Sweden. Science correspondents from several London papers even went to Stockholm to investigate reports of parts of rockets landing in Sweden.

The Berlin Social-Democrat press filled in the local details. Dull explosions from Peenemunde, flashes of fire, pillars of smoke. The Russians had certainly rebuilt Peenemunde and were building and testing out even more deadly types of V weapons than those used by the Nazis. We asked the Russians if we could have a look at Peenemunde and they said, “Sure, come along.” On our way to the tiny Baltic isle, we called in at Karinhall, the famous roistering place of Goering where he entertained his guests to deer-stalking and pig-stabbing parties, followed by gargantuan, mediaeval banquets with oxen, roasted whole in front of the guests.

Lord Halifax, former British Foreign Minister, who signed for a pact with Hitler, and Sir Nevile Henderson, British Ambassador in Berlin, were entertained by Goering at Karinhall. According to the Berlin Social-Democrat press, Karinhall had been given to the veteran Communist leader, Wilhelm Pieck, and he used it for entertaining Russians and German Communists on the same scale as the former Grand Master of the Hunt, Goering.

We were the first western visitors to Karinhall since the war. This castle, which was supposed to resound at night to the red revels of Wilhelm Pieck and his colleagues, was actually a shamble of tumbled ruins. It had been completely destroyed, blown up at Goering’s orders by special S.S. troops as the Soviet armies drew near. It was impossible even to force one’s way through the rubble to the underground air shelter where it is said Goering had a riding-ring established for his children.

The only intact part of Karinhall was a Goering cemetery at the edge of a lovely emerald-green lake. In the centre was a crypt of Goering’s first wife, Karin, a Swede, from whom Karinhall takes its name. Dominating all other tombstones in the little cemetery was an enormous rough granite slab inscribed with the single word “Goering.” It was to have marked the spot where the most cynical and bloodthirsty of all the Nazi gang was to be buried. Goering’s preparations for Valhalla were upset however by the Soviet Army’s rapid advance through Germany. There was nothing left to bury in the Karinhall cemetery.

Goering’s ashes were scattered in anonymity after he cheated the Nuremburg gallows by swallowing poison.

Before we visited Peenemunde I fell ill – of stomach poisoning. My colleagues assured me it was due to an overdose of Soviet hospitality of too much cucumber salad with fresh cream, and washed down by vodka. Whatever the course of the illness, I really experienced Soviet hospitality afterwards.

The Russian woman doctor who was called to examine me decided I must be removed immediately to the Russian military hospital. I did not want to go. My experience of hospitals was that they detain you much longer than necessary, and I was anxious to finish my tour. She was insistent, and so was I. I wanted to remain in my comfortable hotel room at Schwerin, capital of Land Mecklenburg. I won the battle, but half an hour later, the hospital moved into my hotel room – the doctor, a sister and two nurses with an array of ominous-looking rubber tubes, bowls and jugs. The rubber tube was thrust down my throat and deep into my stomach and jugs of warm water poured down the tube.

After the same procedure had been applied to other portions of my anatomy, I was transported to bed by my female echelon, as flat as a gutted eel. The lady doctor examined me and proclaimed that with rest, and a careful diet, I would be saved to write again another day.

There was a lively debate a couple of days later between the doctor and our conducting officer, a handsome young Muscovite, George Krotkoff, from the Soviet Information Bureau. Krotkoff, with my earnest backing, said we must push on with our tour.

The doctor said: “What about his diet?” The solution was a triumph of Soviet organisation.

I was considered too weak to drive my car so a driver was provided. We left the hotel, the doctor and nurses shaking their heads at such lunacy. At each Russian Kommandatura or Intourist hotel at which we stopped to eat, there would be a whispered conversation as to which of the four of us was the invalid – and my precise diet for that meal was set before me. The doctor had telephoned through to each eating place on our tour and had ordered a specific progressive diet for each meal.

As we approached Peenemunde – the first visitors, apart from the Russians and Germans who worked there, ever to visit the island since the Germans turned it into their secret weapon station – we heard the rumble of explosions echoing through a thick belt of pine trees and we smelt the acrid odour of high explosives. There were explosions and flashes all right.

The Russians were just completing the demolition of all installations. Unhappy-looking German girls, under the eyes of tough-looking Russian non-coms, were carrying cases of explosives, as we strolled across, the debris of shattered buildings.

“Hitler girls,” said the Russian colonel in charge of demolitions, “they don’t work willingly.” Those I tried to photograph turned their heads away, frightened of reprisals from former Nazi comrades, if they were recognised as taking part in the destruction of Hitler’s pride, the ace with which he was certain he could win the war.

The Soviet colonel of engineers gave full marks to the British R.A.F. for their raids on Peenemunde. “They destroyed it by seventy per cent.,” he said, “but still they left us the hardest work to do. Now we are nearly finished. We have destroyed every installation above ground and most of those underground as well. There are still two underground wind testing tunnels.”

The German girls were carrying explosives to one of these wind tunnels, and Russian engineer troops were preparing a section for demolition.

The colonel, obligingly, blew it up while we were there so I could take a picture.

“When these two tunnels are completely destroyed then we’ll start on the foundations of the buildings. After that we’ll destroy the roads and railways still left. We are keeping two big sheds until last, to house our staff, but they will go too in the end. After we’ve finished with the roads and railways, we’ll plough up the island and turn it back to the Germans.”

We walked all over the island, inspected the shells and wreckage of fantastic-looking buildings from which the Nazis shot their rockets into the stratosphere, took photographs where we wanted. After a few hours we were convinced that one more anti-Soviet propaganda canard had been shot down.

“Of Peenemunde,” we could and did write, “there is nothing left but the name and rubble.”

“Come back and see us at the end of June,” the Russian colonel said as we left, “our target date for ploughing the fields of Peenemunde is June 30.”

After our stories were published the reports of Russian rocket experiments from the Baltic Coast died overnight. The Chief of Staff of the Swedish Army told correspondents in Stockholm that there was no evidence that rockets or any other guided missiles had passed over or landed in Sweden. The Peenemunde and Karinhall legends were both exploded, but of course, the West Berlin press switched next day to writing in sinister and lurid terms about Russians working the uranium mines in Saxony.

In Schwerin, we called on a Herr Mueller, Christian Democrat, Minister of Agriculture in Land Mecklenburg. A large, burly man who wore an English golfing cap, his whole life had been devoted to agriculture. He resembled an English gentleman farmer who really took an interest in the land.

We asked Herr Mueller how the spring sowing was coming on.

“It’s 92 per cent. completed,” he said, “and by our target date, May 19, it will be 100 per cent. complete.” We were rather astonished at such very precise figures and asked how he could produce at a moment’s notice such an unqualified statement. Herr Mueller was proud and pleased to explain to us.

“The Russians and ourselves make a fine combination,” he said. “They are excellent planners and we are good organisers.

We have learned much from them in the way of detailed planning, and they are impressed with the way we can organise to carry out a plan.

“The whole Land Mecklenburg is divided up into provinces, districts, village groups and finally villages. In each village is the agricultural committee elected by the peasants. We have a liaison officer for each group of villages, constantly in touch with the committees. Every hectare of land is known to us, every cow, horse, pig and sheep is registered with us. We have a complete registry of all agricultural equipment. We know what land is best for grain, which is best for potatoes or sugar beet.

“We help to make the overall agricultural plan on the basis of the data we have here. When we got our plan for spring sowing, it is broken down to allotments for provinces, districts, villages and finally the village committees allot to each individual farm exactly how many acres of wheat, barley or potatoes a farmer must grow.

“My job then is to see the farmers get their seeds and fertiliser in time, that sufficient implements and draught animals are available.

“This year it has worked very smoothly. My village liaison officers make up reports every evening as to how the sowing is coming on and by 2 a.m. or 3 a.m. Yes,” he smiled at our surprised expressions, “we work late hours during the busy season, I can tell you exactly how much is sown and where there are difficulties. Up to this morning 92 per cent. of the total area was sown.

“It is almost like a military operation,” he continued, “I have reserves of seed and fertilisers. I have mobile technical brigades and tractor pools. If I get a report from one district that the sowing is lagging because the seed potatoes have turned bad, I can rush a couple of truckloads of seed to the area. If another area is in trouble due to shortage of draught animals, I can despatch a tractor to the rescue. If there are breakdowns of tractors or seed-drills I can send one of my flying columns to help. All this has improved the morale of the farmers to an enormous extent.

“One other great thing we have learned from the Russians is to improvise and to exploit our machinery to the greatest possible extent. Machinery that farmers had discarded long ago, they have made us organise and repair. Without this improvisation, we could never carry out our plans. And the planning itself is meticulously thorough. Everybody is given a target date for everything he has to do, and for us this is very sensible and necessary. Many of our new settlers have never been used to acting on their own responsibility before. They have been farm servants, agricultural labourers, some of them even city workers. Those who have come from other parts don’t know this type of soil and weather conditions. The great majority of the new farmers, however, have been used to doing just what their boss told them, not thinking ahead from one day’s job to the other.

“Now we have a great scientific organisation that does the strategic thinking for them. After a year or two, of course, they will learn and many things we do now will not be necessary. It may seem ridiculous to you when Marshal Sokolovsky issues a decree that by a certain date, all tractors, ploughs, harrows, seed and fertiliser drills, farm carts and other implements named, must be overhauled and greased, ready for the spring-sowing campaign. But for us, this is very important.

“For many farmers the decree is unnecessary. They are used to planning their work. But it gives our local officials the authority to make the farmers help themselves. For the time being we have to do their thinking for them, tell them what to plant and when to do it, according to the soil and weather conditions which we can judge scientifically.” Herr Mueller explained that he received his plan for Land Mecklenburg-Pomerania from the Central Administration for Agriculture in Berlin. Based on reports from the provinces the Central Administration – now Ministry of Agriculture – submitted each year a plan to the Russian Chief of Agriculture Division. The Soviet officials might make some amendments, suggest more potatoes than wheat, more maize for fattening poultry, and less beet for sugar, more hops for beer and less fodder for cattle.

Once agreement was reached, the portion affecting each land was sent to the respective ministries of agriculture for putting into effect.

“When the crops are well advanced,” continued Minister Mueller, “we make sample checks of the yields. On the basis of that, we fix the quotas which each farmer must deliver, making allowances for local conditions, bad quality soil in one area, shortage of rain in another – and the size of the farmer’s holding. The quota system is so arranged that the main burden of deliveries falls on the wealthy farmers. We encourage the farmers to sell their surpluses through the co-operatives instead of on the free market, by allowing them to buy equipment at the co-operatives at fixed low prices according to the amount of produce they have turned in.

“And the beauty of it all is,” he concluded, “that it works, works beyond our most optimistic hopes despite, at times, seemingly insuperable difficulties. Russian planning, German organisation and hard-working German peasants. It works. We get our crops sown on time. We collect our grain quotas. The city worker gets his rations and the farmers get their consumer goods.”

We toured around among the villages, spoke to farmers and assured ourselves that it was working. Almost a year had passed since I talked with the peasants at Seusslitz, but the types – and the developments – were the same everywhere. Here in Mecklenburg, the new houses were no longer in the blue-print stage. They were there, fastened to the very soil the new settlers had been given. Small but solid brick houses, with stables attached, everything under one roof, so that animals could be tended in winter without moving out of the house. Houses with electric light and running water.

The suspicion and uncertainty which I had seen at first on the faces of the Schloss Seusslitz “Neusiedlern” had disappeared from the faces of those in Mecklenburg who now had their own homes, with brightly polished stoves and something good cooking on them. Life had started again, roots had crept back into the soil and found firm support. No use trying to talk these families into returning to their old farms east of the Oder-Neisse. Most of them had homes, better than those they had left; they were well on the road to a better and fuller life.

They made poor raw material for the propaganda with which they were bombarded by the West Berlin and West German press, demanding that the lost lands be recovered and the “expellees” returned to their old homes. The rich former land-owners from the east, formed into associations pledged to the return of East Prussia, Silesia, Sudetenland, and the rest of Germany’s lost territories, could no longer count on the new settlers in the east to fight for them. The new roots had taken too firm a hold to be shaken by irredentist propaganda.

Berlin itself – this city for which the Western world (behind the backs of the general public, of course) was being asked to fight another world war – was, in 1949, the most demoralised, corrupt and hopeless city in Europe. At least, the Western-occupied three-quarters was. Military government officials supposed to be running the city had their hands deep into the black market.

The whole Western-occupied section was being run on a black-market basis – and this long before the blockade was imposed. The black market was fed primarily from American military stores. Black market deals involving high military government officials came to light – and were quickly covered up – every few weeks.

On one occasion a press officer on General Howley’s staff telephoned his opposite number in the British sector. He wanted a telephone installed as soon as possible in the shop of a dressmaker friend of his in the fashionable Kurfurstendamm, in the British sector. Would the British arrange the necessary priorities and have it set up “right away”? The dressmaker’s shop was one used extensively by American clientele, and it was very annoying for the American wives not to be able to arrange things by telephone.

The British officer, Mr. John Trout, replied somewhat testily that there was a great shortage of telephone equipment and it was available only for essential purposes. If the captain wanted a telephone installed he had better forward an application, giving full details, etc. The captain was very hurt at this uncooperative behaviour – especially in view of Marshall Aid, dollar loans and the rest – but sent in an application giving full details of business turnover and other essential data.

The details were of such interest that the telephone branch turned them over to the Economic Department of British Military Government. Textiles were severely rationed in Berlin. Each dressmaker’s shop or modesalon got a very limited amount each month, which was supposed to be sold only to people with coupons issued by the City Council. The turnover figures for this particular shop were about one hundred times as much as normal business would justify.

Enquiries were made on the spot, and as a result a couple of British military trucks arrived and were loaded up not only with black-market textiles, but also with a few thousand packets of American cigarettes and a few hundred pounds of American coffee. At that time it was illegal for Germans to possess any goods originating from Allied military sources.

There were furious telephone calls from Colonel Howley’s office to that of the British public relations officer.

“Is that the way we’re supposed to co-operate?” demanded the captain, his voice choking with anger. “You British swooping down like that and confiscating my property?”

“Your property?” demanded the urbane Mr. Trout.

“Of course, my property. I just had it stored at my friend’s place for safe keeping.”

“Well, there’s a certain section ... just a jiffy and I’ll give you the address where you can send in an application, and if you can prove the goods are yours, you can probably get them back again.”

The last I heard of that particular case, the captain was still trying to get “his” goods back. They had, of course, been accumulated by his girl friend, charging in kind for the favours she rendered her American clients.

A typical story from the gangster section of Berlin was that of Prince Ferdinand, son of Princess Hermine, last Empress of Germany. She was the second wife of World War I figure, Kaiser Wilhelm. After Wilhelm died in exile at Doorn, in Holland, the Princess Hermine was allowed to return to Germany. She lived in retirement in Frankfurt-an-der-Oder. When the Soviet troops arrived, they quartered some officers in her house, but she was treated with respect and allowed to live a quiet life. Her daughter, Princess Caroline, a pale, pleasant-looking blonde woman, who lived in the British sector, was allowed to visit her frequently.

The Princess Hermine owned a considerable wealth of jewels. Part were the crown jewels of the Hohenzollern family, part were from her own family. Some of them the Princess kept with her at Frankfurt, others she had sent to Berlin, entrusted to the safe- keeping of Prince Ferdinand. He kept them locked up in a trunk, but told one of his bosom friends among the Americans, a White Russian, Prince Michel Scherbanin, who worked with the American Gestapo, the Counter Intelligence Corps, or C.I.C. as it is generally known. The prince managed to persuade Ferdinand that “the Russians were on his track,” and as Ferdinand was a weak young man, with a past sufficient to give him a guilty conscience where Russians were concerned, he believed the report, and was persuaded to move from his flat into Prince Scherbanin’s apartments – together with the trunkful of jewels.

He was told never to move outside the door. After a week or two, he was told the Russians had “caught up with him again.” Soviet agents were patrolling the street. He must be moved again, at dead of night. An apartment had been arranged for him in another part of the American sector. Again, he must never move outside. After a short time there, he was moved again, then again. Eventually he got tired of moving from flat to flat and living behind locked doors and drawn curtains. He walked out of his hide-out apartment late one night, and returned to his own flat. He telephoned Scherbanin to return the trunk-load of jewels immediately.

Incidentally, Prince Ferdinand, despite the jewels he had been more or less sitting on, had been having a tough time financially in Berlin.

Unemployed princes rated the same as anybody else on the grim ration scale. He was more fortunate than some, however. A British officer who was enjoying the favours of Ferdinand’s wife – a Wagnerian blonde who sang in night-clubs under the name of Rosa Rauch – found the prince a job driving a taxi for the British press.

The officer in question found it piquant to have his breakfast sent over to Rosa Rauch’s apartment in the taxi driven by the princely cuckold.

It was to this apartment that Ferdinand now returned, and it was 2 a.m. when the trunkload of jewels arrived. He was not sufficiently awake at that hour to inspect the trunk in the presence of the person who delivered it. When he opened it next morning, he found that fifteen of the most precious items were missing.

He immediately informed the American police, and then his troubles really started. In the meantime, Princess Hermine died at Frankfurt-an-der-Oder. The prince’s girlfriend, a massive brunette, was arrested by the American police on alleged suspicion of having murdered the aged Empress. Some jewels found in her possession were confiscated. She had been visiting Frankfurt frequently, it appeared, and had brought back some more jewels to be added to the collection in the trunk. (It turned out that Princess Hermine was negotiating to buy a tourist hotel at Hitler’s Berchtesgaden Eagle’s Nest.)

The Princess Caroline arrived back from her mother’s death-bed, with jewels given her by her mother, which she brought back to Berlin with Russian permission. Her flat in the British sector was searched, the Princess herself was searched, and all jewels confiscated by the Americans.

Where treasure was concerned the Americans acted like bloodhounds. Their only legal interest in the matter should have been to help Ferdinand get his lost jewels back. Princess Hermine had died in the Soviet Zone of a throat disease, as testified by Soviet doctors. She had every right to dispose of her private fortune as she chose. Her daughter and even the Prince’s girl-friend had a perfect right to have jewellery in their possession. The Americans had no right to search premises in the British sector. But with treasure in the air, they were indefatigable.

The U.S. police chose not to believe Ferdinand’s story, and were very indignant that one of their officers had been mentioned. The Prince and Rosa Rauch, who had returned to him in the meantime, were both arrested. After many hours of third-degree questioning, Ferdinand – against his will, he maintains – was injected with a “truth drug.” The rest of the jewels in the trunk, needless to say, were confiscated.

Ferdinand told me, later, that he was given a massive injection from a huge hypodermic syringe, which knocked him out for a day and a half. He was probably as much stupefied by the rush of events as by the drug. He said he had no idea what questions were asked of him or what answers he gave, but that he was in a very “confused” state about the workings of American justice.

First forced to live a hermit life on absurd pretences, then half his jewels disappear; arrested because he reports the fact; his girl friend arrested on a murder charge; his wife arrested because she was with him; his sister searched – and all the rest of the jewels confiscated. Enough to set even a princely mind in a whirl!

Eventually he was freed, his wife and girl-friend also. Ferdinand immediately “fled” to the British sector. Some of the details in this mystifying case began to leak out in the press, with the Russian announcement of the death of Princess Hermine and a statement by Ferdinand about the loss of his jewels.

The day following these announcements, the Americans started putting pressure on the British to arrest again, this time on a charge of falsifying his “fragebogen” (a detailed questionnaire relating to one’s political past). While this was going on, arrangements were made for the funeral of Princess Hermine.

Her body was brought back from Frankfurt-an-der-Oder for interment in the Hohenzollern family cemetery in the beautiful Sans Souci park of Frederick the Great, at Potsdam. The Russians made the necessary arrangements and waived formalities so that the few press representatives interested could attend.

There was something bizarre and incongruous about the whole affair. The journey through the crumpled buildings of once lovely Potsdam; the deadness and shabbiness of this destroyed garrison town of barracks, palaces and churches, the pompous official at the gates of Sans Souci who refused to let anyone enter the “private park of the Hohenzollern family” (even Russian officers were turned back at the gates until orders arrived from somebody very high up in the Soviet administration that the gates were to be opened). The crowd of musty Hohenzollern retainers who looked as if they had stepped out of last-century oil paintings and would step back into their frames again as soon as the ceremony was over; the beautifully kept park, modelled on Versailles, and the simple chapel and the black-gowned bishop and the plain black coffin and a few wreaths.

There were shocked expressions on the faces of the retainers and relatives as American photographers clambered along the top of the chapel doors shooting flash bulbs every few seconds; again when American correspondents, demanding to know where were the missing jewels, buttonholed Princess Caroline as she emerged, pale and weeping, from the chapel.

It was a scene which could only have been enacted in the Berlin of that period. All were shocked at the crude behaviour of the Americans. In addition to private grief, it was an historic occasion. It was almost certainly the last time a member of the Hohenzollern family would be buried at Potsdam. The internment of Princess Hermine marked the end of an era.

Only one available member of the family was not present at the funeral. That was Prince Ferdinand. On the very night of the funeral, after further insistent calls from the Americans, British police officials arrested him – in his pyjamas, in his British sector flat – and charged him with falsifying his “fragebogen.” Ferdinand had omitted to state, when he took the job as taxi-driver at the British press camp, that he had joined the S.S. in 1930. The Americans had a monopoly of information on this subject, for they had complete files of Nazi party membership. They often made use of this when they wanted to arrest somebody for other reasons – and who knows how many times it has been used as a threat to purchase loyalty from their agents?

I visited Prince Ferdinand in his prison cell while he was awaiting trial.

He is not a pleasant individual. War injuries have given him a heavy cast in one eye and the most dreadful form of stutter I have ever encountered – a stutter which starts in his stomach and makes it flap in and out like a sheet on a windy clothesline.

He made sure I was not representing a Communist paper before he would talk to me. He was still numbed by his treatment at the hands of the Americans.

“I turned to them as friends,” he said, “expecting justice after my jewels were stolen. And they treated me as a criminal.” He went on to relate the story as told above.

“But why did you fall for the story that you were being shadowed by Soviet ‘agents'? What have the Russians got on you, anyway?”

“You see, it’s true that from their viewpoint I’m a ‘bad hat.’ Of course I’m a Junker and a militarist. I did serve in a ‘Death's-head’ unit in Russia during the war, where we used to bump off Commissars and people like that. And when my American friends told me I was in danger, of course I believed them.”

“What about the charge that you were a member of the S.S.? Is that true?”

“I don’t think so. What is true is that in the 1930s, I used to knock about with friends who were in the S.S. That’s when I lived in the Ruhr. You know how it was in those days. The ‘Reds’ were very active, and we used to go out and bump some of them off at night. That was in Cologne. But then, after Hitler came to power and the Nazis turned against the aristocracy, I had nothing more to do with them. My family moved up to the Baltic Coast. I did receive a card by post once, showing me to be a member of the S.S., but I mailed it back. I never paid a fee or attended a meeting, never wore a badge or uniform.”

Ferdinand was sentenced to nine months imprisonment by a British military government court, but was released on appeal shortly afterwards.

And the jewels? They were removed to Frankfurt for “safe-keeping,” and up till the last I heard they had never been returned. As for those missing from the trunk, nothing further was heard of them.

Only the Berlin of the occupation period could have produced such situations.

Corruption and demoralisation seemed to have set up a chain reaction, from Germans to occupiers and back again. Misery and despair on one side, luxury and greed on the other. Jewels, cameras, art treasures or actresses, were all to be had for a few cigarettes or a little coffee – and the Allies had a monopoly of these commodities. From the highest officials to the private soldiers, all were engaged in a wild scramble to turn their occupiers’ privileges into concrete assets.

So many high British officials were engaged in racketeering that the Chief of the Civil Affairs Division (equivalent to Minister of the Interior), Mr. Julian Simpson, brought out a special team of detectives from Scotland Yard to investigate and prosecute racketeers in the British Control Commission. Within a few weeks, Tom Haywood, who headed the team, had a case-book involving chiefs and deputy-chiefs of divisions and high-ranking military officers. In one instance crate-loads of valuable German furniture and carpets had been flown back to England; more crates still stood on the Gatow airfield in the British sector, awaiting plane space.

Simpson and Haywood demanded prosecutions, and the files were sent to London. For reasons of “prestige” (“ what would the Soviet-licensed press say?"), it was decided to hush matters up. Mr. Simpson resigned his position and went back home to Australia. Mr. Haywood was transferred away from Berlin to the Zone, where he could busy himself with less important personalities. In some instances, however, there were checks made in homes in England, and crates of valuable carpets, oil-paintings and other valuables were flown back to Germany.

One British Public Safety official in the Zone, who objected to prosecuting the small fry while the big ones were left unscathed, told me: “Every time they came to me and asked me to investigate some soldier who’d been ‘flogging’ a few cigarettes, I’d open up my files and say, ‘Let me get after these chaps and I’ll take on the little fellows afterwards.’ And in that file, I had some of the biggest names in the British Zone,” he added.

One could dig into the affairs of almost any Allied organisation in Berlin and discover graft and black-marketeering.

E.C.I.T.O., for instance, was a United Nations organisation (European Control Internal Transport Organisation) set up to organise some sort of order out of the chaos of Europe’s rail, road and water communications after the war. One of the Berlin secretaries provided me with copies of correspondence to show that Berlin personnel were engaged in widespread illicit trading.

E.C.I.T.O. trucks were being used to smuggle goods through to Luxembourg, where they were distributed all over the world. Machine-needles by the hundred gross were offered, according to letters I have in my files, through E.C.I.T.O. agents in Paris and London to firms in the Middle East and India. Goods packed in E.C.I.T.O. boxes or trucks painted with E.C.I.T.O. letters were never searched at the frontiers.

When I turned my file over to Haywood of Scotland Yard, he sighed and said: “I can’t touch it. With my forty men, we are so up to our necks with following up our own cases here, that I haven’t a man to spare for this one. This would mean sending men to Paris, London, Brussels and Luxembourg. As American military officers are involved, I’d have to have American permission to follow it up, too.”

Nothing was ever done about it, and the officials concerned will probably live happily and untroubled for many years off their occupation investments.

Where one Allied official was involved, there were usually ten Germans – paid in U.S. or British cigarettes

On January 14, 1948, certain British correspondents in Berlin were called together by a British political intelligence officer. I was in Berlin too, at the time, but was not invited. The correspondents were shown part of a document of which the officer said, “there is absolutely no doubt of its authenticity.” The top and bottom parts of this document were folded over, concealing the origin and signature, date of issue, etc. Written in pseudo-Marxist language, the document, known as ‘Protokol M’ consisted of a preamble and five sections.

“The coming winter will be the decisive period in the history of the German working class,” the preamble started.

“This battle is not concerned with ministerial posts, but is for the starting position for the final struggle for the liberation of the world proletariat ... The working class of every nation will provide the necessary assistance.

The five-point programme called for:

(1) Strikes against transport to disrupt food supplies.

(2) Agitation cadres to be formed to exploit weaknesses in Social Democrat organisations.

(3) The organisation of secret radio stations. Names of supposed organisers were given. “We must guarantee that receiving sets are installed in good time and secure places.”

(4) Strike cadres were to be organised by the end of February, organisation of a general strike would begin in early March.

(5) “M. A. Cadres” were to be placed in charge of the strike. (A most unlikely quotation from Lenin was used to bolster up the rest of this ridiculous document: “He who places at the top of his programme political mass organisation embracing all the people, even before his tactics and organisation, runs the least risk of failure in the revolution.”)

The chosen correspondents were told that “Protokol M” would be published in the French licensed evening paper “Kurier,” that evening; that their stories should be based on “Kurier” and not on British Intelligence; but they could say that British intelligence had known of the existence of this document for some time and had no doubt of its genuineness.

The correspondents waited around with considerable impatience for the evening issue of “Kurier.” Eventually it came – but with no mention of “Protokol M.” The telephone of the intelligence officer was soon ringing and half a dozen indignant journalists wanting to know what was going on. Was that his idea of a practical joke? He was very astonished that it was not in the paper and begged them to call him back after half an hour. Some harsh words must have passed between him and his French opposite number, for within half an hour the British officer was able to tell the correspondents that there would be a special edition of “Kurier,” later in the evening with the story. Sure enough, a few hundred copies of “Kurier” were run off later that evening carrying “Protokol M.” It seems that the editor had stagefright almost at the last moment and had decided not to carry the story, but heavy pressure was brought to bear.

The most enraged man in Berlin that night was Arno Scholtz, editor of the British licensed Social Democrat paper, “Telegraf.” Normally Scholtz did not shrink from publishing the most outrageously false stories. He had “Protokol M” in his pocket for some weeks; had even taken it to London with him and tried to sell it to a London newspaper. It smelt too much like the infamous “Zinoviev letters” forgeries, published by the British Tories on the eve of the 1924 general elections to discredit the Labour Party, to the particular editor to whom Scholtz offered his story. He turned it down, and Scholtz did not raise the good English pounds he had been seeking. As the story was turned down in England, Scholtz was dubious about publishing in Berlin. There is no doubt at all that Scholtz knew the document was a forgery, but still he was furious at being “scooped” by a rival paper.

Next morning, the story made a sensation in the British and shortly afterwards in the world press. Properly trimmed with guarantees of British intelligence, quotes from officials in the British Zone that sabotage had already started, stories that troops were being moved to the Ruhr as precautionary measures, “Protokol M” became the sensation of the year. The following day the British Foreign Office released the full text, with a pompous statement that “It had been known to the British authorities for some time.”

On January 21, Mr. Hector McNeil, assured the House of Commons that “His Majesty’s Government believes this document to be genuine.” He also added to quieten the suspicions of some members that the German press had obtained copies of the document “by the ordinary methods of news gathering” and its publication was made “quite freely and without instigation by us and as far as we know by no other government.”

Pravda nailed the story for what it was, a “villainous forgery circulated by British intelligence in order to justify the repression which is being prepared against democratic movements in German.” As Communist newspapers were being closed down right and left at that time, the SED and People’s Congress had been banned in the Western Zones, Pravda put its finger well and truly on the spot. “Protokol M” was a good illustration of the type of incident which the lunatic fringe in military government were capable of manufacturing. “Protokol M” was to be the prototype for future provocations to turn the “cold war” into a “hot” one.

It was not until three months that Mr. Hector McNeil had to eat his words and make a painful admission to the House of Commons that the document was a forgery. Meanwhile the damage had been done and repressive action against the Communists was in full swing.

“Mr. Bevin,” stated McNeil, “decided that the most careful and exhaustive investigations should be undertaken. These eventually led us to a German, not employed by H.M. Government, who, after questioning, volunteered that he was the author of the document. I have read a summary of his statements and I must tell the House that they are not convincing and that they are in parts conflicting. The Secretary of State, however, wishes it made plain that after these further investigations, we can only conclude that the authenticity of the document now lies in doubt.”

All of which was Mr. McNeil’s roundabout way of admitting the truth of Pravda’s terse comment that “Protokol M” was a “villainous forgery” perpetrated if not by, at least with the knowledge of British intelligence.

To this day the name of the forger has not been released, nor his position. In Germany, it is widely accepted that the person referred to by McNeil is a leading functionary in the British Zone organisation of the Social Democrats. The only action taken against the intelligence officer who palmed the story on to correspondents was that he was transferred to the British Zone.

An amusing sidelight to the “Protokol M” story for me personally was that while I was unsuccessful in dissuading most of my colleagues from lending themselves to such an obvious “phoney,” I was successful with Leo Muray, of the Manchester Guardian. He arrived in Berlin from Vienna on the evening when the story was released. I told him of it and my reasons for disbelieving it. It was “supposed” to have originated in Belgrade in the “autumn” of 1947. What serious person and what Communist would take notice of a document which bore no exact date, no address of origin and no recognisable signature? What Communist would use such a roundabout quotation from Lenin, the only purpose of which could be to justify the stupidity of the tactics outlined in the document – and to introduce the word “revolution”?

After some discussion, Muray agreed with me and did not send the story. Next day, with the story splashed all over the British Press, Muray got an angry message from the editor, demanding to know why he had not sent the story.

After Hector McNeil’s April 19 statement, however, the Manchester Guardian came out with an article preening itself for its acumen in having discarded a story which was so “obviously” a doubtful one.

“The Foreign Office,” wrote the Manchester Guardian, “comes rather badly out of the episode of Protokol M. It accepted as genuine a document which, even to uninstructed observers like ourselves, appeared to be doubtful on the internal evidence alone. Gullibility is the worst possible vice of an intelligence service. Those who swallowed ‘Protokol M’ might well be released to seek their fortunes writing thrillers for the commercial market.”

“Protocol M” is a forgery which deserves to stand with the “Zinoviev Letter,” the “Protocols of Zion,” the “Reichstag Fire,” and other villainous provocations invented by reactionaries to justify oppression. It was exploded in the U.S. Congress in the middle of the debate on Marshall Aid and was used as an argument for the need of American dollars to save Europe from Communism.

There were many similar clumsy tricks pulled out of the armory by the Berlin professionals in political warfare, disguised as information and intelligence officers. Crude and stupid as many of them were, the plots sometimes misfired to the temporary embarrassment of the governments concerned.

One enthusiast in the British I.S.D. (Information Services Division) produced a plan for “counter-propaganda” working through the German press and certain British journalists (the B.B.C., Reuters, News-Chronicle and Daily Express were to be excluded). A definite programme of prefabricated stories was to be floated for simultaneous release to British and German correspondents. An exact list of stories was contained in the memorandum produced by the official concerned.

It included the following “news” stories:

Unfortunately for this particular officer he was so intoxicated with the brilliance of his brain-child that he talked about it too often and too openly. A summary of his memorandum appeared one day in the Soviet licensed “Berliner Zeitung.” Of course the story was immediately denied, but the I.S.D. officer was quickly whisked off from Berlin to the British Zone with stern admonitions to keep his mouth closed in future.

The programme of stories however went through, with a few alterations as to the order in which they would be published, and a few additions. One of the more recent campaigns in the West German press was in preparation for the demand for a German army in the West. A series of stories was released about the People’s Police in the Soviet Zone, pretending that it was a vast army in police uniforms, complete with tanks, artillery – and one paper added – planes as well. The Sozial-Demokrat, to cover up the fact that the French were using German troops to crush the independence movement in Indo-China, claimed Soviet Zone people’s police were fighting with the democratic forces in Greece. It even published a large list of names and home-towns of those supposed to have been killed fighting in 1949. “Neues Deutschland,” the S.E.D. newspaper, checked every name in every town. In some cases no such people as mentioned existed, in other cases the names existed but in no case did a name correspond with anybody who was a member of the Soviet Zone police force. But for every lie that was crushed a dozen more were invented by the Goebbels-trained journalists working for the social-democrat press.

One of the crudest efforts perpetrated by British intelligence in Berlin was the production of a “pro-forma” questionnaire, which any British officials having dealings with Russians were supposed to complete about the particular officials with whom they came in contact.

The document was marked secret, was printed by the firm which did all British official printing in Berlin, and by the nature of the questions, it was clear that the questionnaire referred only to Russians.

A copy of this was left one day on a table after a Control Council meeting in the Allied Control Building. Either it was left as a friendly warning by some sympathiser or it was meant as a subtle means of increasing Russian suspicions and forcing them to break off those social relations which still existed. From the moment that document was known to the Russians, they could justifiably expect that every British official with whom they came in contact was a spy.

The “pro-forma” was sent around to various British officials with a memo, stating if they had any doubts about filling in such forms, they should ring a certain telephone number. A British intelligence officer who answered at that number would then allay their scruples. Several of the questionnaires were returned to the issuing officer with angry notes from officials who said they had not come to Germany to spy against the Russians.

The questions concerned the military rank and branch of service, decorations worn, languages spoken, region in Russia where the official was stationed (to make it quite clear that the questionnaire was for use against Russians it said with regard to the last question, “e.g., White Russia, Ukraine, etc.”), whether subject had been abroad before and other routine questions of military intelligence.

The face of the intelligence officer who was supposed to quieten one’s scruples was a fine purple of anger and embarrassment, when I dropped a photostat copy of the document on his table one morning and asked him what it was all about.

Eventually, amid mumbled threats of the Official Secrets Act, he muttered something about “mere routine enquiries” for information which helps Control Commission officials “to deal with their Russian opposite numbers.”

A facsimile of the “pro-forma” eventually found its way to the British and German press and British-Soviet relations were dealt another heavy blow. And this brings us to the subject of social relations between the Russians and the western allies.

Any newcomer to Berlin, certainly any newcomer in the press world, was told that it was impossible to see any Russians. “They never even answer their telephones,” one was told by the official liaison officers.

Stories were spread that no Russian could visit a westerner without permission from his superior officers; that any Russian having social contacts with westerners came under suspicion of the Soviet police, and if he persisted in his contacts he would “disappear,” that those few who did have contacts were “police spies.”

Far nearer the truth was that British and Americans having friendly relations with Russians were regarded with the greatest suspicion and if they disregarded hints, they “disappeared,” or, in the western way, they were declared “redundant” and sent back home. This happened in a number of cases, especially to friendly British-Russian liaison officers.

From the time I arrived in Berlin at the end of 1945 until the time I finally left Germany in April, 1949, I had close and continued social relations with Russians. Of the half dozen who became my good friends, five were still in Berlin when I left, the sixth had been transferred back to Moscow, where I kept track of him through his articles on Germany which appear regularly in the Soviet press. I invited them – and they came – to my flat and the British Press Club.

They invited me – and I went – to their flats and to the Soviet Press Club. If they accepted an invitation, they never failed to come.

At the British Press Club, my Soviet guests were usually joined by several British correspondents and other guests of the club. Discussions ranged over the widest variety of subjects – and no holds were barred on either side. I could drop in at any time to the Soviet Army newspaper “Taegliche Rundschau” and see the editor, Colonel Kirsanoff, and this applied to any other correspondents interested enough to the attempt.

In the early days of the breakdown of the Allied Control Council, at the time of the collision between the British Viking air-liner and the Soviet Yak fighter plane, when official relations were at their lowest ebb, Marshal Sokolovsky’s aide, Colonel Prishepniko came to a dinner party at my flat, together with General Robertson’s public relations officer, Richard Crawshaw, and Colonel Howley’s public relations officer, Fred Shaw. Shaw and Prishepniko had a vigorous verbal duel over American intervention in Greece, but the dinner was a great success. Prishepniko, who is a tall, exceedingly handsome and intelligent officer, learned excellent English when he served with a Soviet tank-purchasing mission in the United States.

There was no difficulty in having friendly contacts with the Russians if one went to the trouble of getting to know them. Many people complained that the Russians did not come to their cocktail parties when they were invited.

My Russian friends explained that they were excessively bored with cocktail parties, and bored in general with being treated like “museum pieces” by gushing Allied wives who were just “too thrilled” to actually talk to, and touch a Russian. It was something to write home to one’s friends about. The parties the Russians liked and the invitations they accepted, were to smaller, more intimate affairs with people they knew and liked and with whom they could have interesting discussions. Most or them were good linguists and spoke either English or German or both. Those from the press world with whom I had, naturally, the closest contacts were extremely cultivated people, with a knowledge of European literature and drama that put most of their hosts to shame.

The mistake that many British and American correspondents made, once they did make contact with their Russian opposite numbers, was to try and exploit them as a news source. They would telephone on all sorts of occasions, hoping to get a “beat” on their colleagues with some meaty quotes from Soviet sources. And, of course they were always disappointed. There were no “leakages,” official or otherwise from Soviet sources, such as correspondents were accustomed to from their British or American contacts.

If one approached the Russians as human beings and not as “news sources” one made fine friendships with polished and cultured men and women, with whom it was possible to enjoy a first night at a theatre or opera and have a stimulating discussion together over supper afterwards. But to try and worm out of a Russian official what the Soviet attitude was going to be to a certain proposal coming up for discussion at the Control Council, was to risk being regarded as a spy. A Russian regards the premature disclosure of government policy as treachery, and it is certain that many social contacts which could have been developed were broken off by this insistent prying into a Russian’s official business which is considered normal in the west, over a few drinks, but which is unthinkable with Russians.

There were those amongst Allied officers who deliberately tried to sabotage Allied-Soviet social relations from the first days. There were the liaison officers who wore their Tsarist or White Guardist decorations and made loud anti-Soviet remarks at the Control Council buffet, who paraded the fact that they were intelligence officers and deliberately tried to arouse Soviet suspicions. It is quite possible that the “pro-forma” mentioned above was intended for this purpose when it was seen that the earlier line – that it was impossible to have social contacts with these “Soviet bounders” – had failed and increasing numbers of western officials were making friends with their Russian opposite numbers. “If one can’t drive the British away from the Russians, let’s try driving the Russians away from the British” was the attitude of one Colonel of liaison that I knew.

A favourite form of sabotage was for Allied liaison officers to hold up letters sent to the Russians and then blame the Russians for the resultant delays. On several occasions I and other correspondents had applied for transit passes through the Soviet Zone and had been held up for more than a reasonable time. Our enquiries produced the standard excuse: “You know what these Russians are, chaps.” Eventually we found the requests had never been sent to the Russians.

A particularly cheap and crude snub to the Russians was administered by the “wrecking section” in British Public Relations. Several tours of the Soviet Zone for British correspondents were arranged by the Soviet press section. On those trips, British correspondents were hospitably and correctly treated. Food, lodging and petrol for our cars was provided free of charge. We were taken to the places we wished to visit and as far as possible interviewed those officials we desired to. We were treated as honored guests, in a warm-hearted and friendly manner.

When Soviet correspondents desired a return trip, after months of negotiation, arrangements broke down, because the British officer conducting the negotiations, Colonel Gillespie, demanded payment in advance, for petrol, food and lodging. Payment had to be made in British occupational currency, which, incidentally, was illegal for Russians to hold.

Such treatment was a challenge to British honour and hospitality. At the same time a large group of German editors were invited to England as the “guests of His Majesty’s Government.” A group of Czech correspondents were expected in the British Zone (these were the days when the West hoped to woo Czechoslovakia away from the Soviet sphere) and orders were given to Public Relations officials to “entertain them lavishly, all costs to be borne by the Foreign Office.”

A special meeting of the British Press Association was called to discuss Gillespie’s snub, and it was decided that the correspondents, many of whom had experienced Soviet hospitality, would pay the cost of the tour out of their own pockets. When this reached the ears of Colonel Gillespie, he finally decided the trip could be arranged, cost-free after all.

In the end the tour turned out a complete fiasco. A schedule agreed by the Deputy Military Governor, Major-General Brownjohn, was repudiated by the Zonal Commander, Major-General Bishop. Half the places to be visited were struck off the list, soon after the tour started. A highly embarrassed British conducting officer, Major Donald MacLaren, tried to do a correct job, kept cabling Berlin and receiving fresh instructions, which were promptly countermanded by General Bishop who did not want Russian journalists looking at munition plants that should have been dismantled. In the end the trip was abandoned and the Soviet journalists returned to Berlin to lodge an official protest about the way they had been treated.

The only Russian-speaking liaison officer at British Public Relations was declared “redundant” because she did her best to smoothe out the difficulties and maintain correct, friendly relations with her Soviet opposite numbers. After she left no one was appointed to replace her and one more line of contact with the Russians was snapped. By mid-1948, there was no official means for a correspondent to contact the Soviet press section – although German journalists and editors were being pressed on to us from all directions.

Correspondents who came from London to see the Soviet Zone were usually “informally” directed to myself or the dismissed liaison officer if they insisted that they wanted to meet Russians. In that way a special correspondent of the London Times, a B.B.C. commentator and a well-known Fleet Street foreign editor were able to visit the Soviet Zone with the minimum of formalities – at 24 hours’ notice.

The wreckers left no tricks unplayed however to ensure that visitors from outside would have no contact with the Russians. Deceit and downright lies were part of the stock in trade.

The Allied Control Council on December 30, 1946, passed an important decree in the spirit of Potsdam for the speeding up of the “complete elimination of German war potential.” It had previously been agreed that enterprises classified as Number 1 war plants and military installations would be destroyed by June, 1947. The Control Council decree of December 30, 1946, provided for four-power teams to tour the four zones, inspect the plants reported as destroyed and in general to ensure that there was no illegal manufacture of arms in these plants and that no undestroyed war potential remained.

In the early days of occupation, military and economic Intelligence experts had co-operated splendidly to draw up lists of plants and objectives which could be regarded as “war potential.” It was a comprehensive list covering thousands of installations ranging from the great bunkers in the centre of Berlin to submarine pens in Kiel, underground airfields, research stations and testing fields for secret weapons. Everything, in fact, brought to light by the pooling of four-power intelligence.

Each occupying power was responsible for the destruction of installations in his own zone. The agreed method of checking on demolitions was that each military governor would submit a list of the installations which he claimed as destroyed and teams from the other three occupying powers would select sample plants from the list for spot inspection.

The scheme worked splendidly at first. I talked with British and American officers who took part in the first inspection tours in the Soviet Zone. They were enthusiastic about the thorough-going way in which the Russians carried out their demolitions. They were given, so they assured me, every facility to inspect installations, were offered every hospitality and were satisfied that the Russians really meant business in the matter of “elimination of war potential.”

The Russians, however, were soon critical of the rate and type of destruction being carried out in the western zones, particularly in the British Zone which carried the greatest weight of military installations. They listed large numbers of plants which – far from being destroyed – were actually producing. They listed underground airfields, shipbuilding installations at Wilmershaven, even the great bunkers in the British sector of Berlin itself, which were undestroyed. Even plants inspected as destroyed in many cases fell far short of Soviet standards. In many cases the buildings, rail tracks and other gear were left to move the machines right back in again.

The wreckers in British and American headquarters began to be anxious about this Soviet “prying into their affairs.” Somehow or other it had to be stopped. Those whose self-appointed task it was to prove to the public in the west that any co-operation with the Russians was impossible, did not even inform the press that inspection teams were wandering about the Soviet Zone, checking up on de-militarisation. It would have spoilt the barrage of propaganda about the “impenetrable veil” which made it impossible to know what was going on in the Soviet Zone. The “Zone of Silence,” they allowed it to be called in the West-licensed press.

I stumbled across the story by accident in an interview with General Draper, at which was present the foreign editor of a great London daily paper. The latter could not believe his ears when Draper mentioned that joint British-French-American teams were wandering about in the Soviet Zone. An interview was arranged with members of the first teams to return. It is a striking commentary on the policy of top occupation officials that no press release was put out in this very important development in four-power relationships.

It was indeed a fact that news of this type was always suppressed, either at source or by the public relations chiefs. If there was something positive to report in the way of four-power co-operation, trade agreements between the Soviet Zone and the west, it was always left to the correspondents to dig it out for themselves. If there was anything that could be given an anti-Soviet twist, the Roneo machines were soon churning it out as a press release or the public relations officer whistled together a press conference.

This particular story, which cut clean across the propaganda of the day, was unfortunately published in a somewhat garbled form which made it appear that Allied teams were wandering around in the Soviet Zone checking up on ordinary industrial production.

The day following the publication of the story, I was invited to lunch with Mr. Christian Steel. I guessed the reason for this honour and took along a carbon copy of my original story. After he had broached the subject over coffee, murmuring that such “irresponsible” stories do a lot of harm, I explained the garble to him and showed him my original story.

“But that’s even worse,” he exclaimed indignantly when he had read it, “there’s not a word of truth in it. We have no teams checking up on demilitarisation in the Soviet Zone. That’s sheer nonsense. Whoever told you this poppycock?”

We had a heated discussion for several minutes, during which I told him of my interview with General Draper and later with members of the teams who had just returned from the first inspection tours. I listed some of the plants they had inspected and their impressions.

Incredible as it may seem, Mr. Christian Steel, then Chief of Political Division and shortly afterwards Ambassador Steel, chief political adviser to the Military Governor, who had stood me a lunch to deny an “irresponsible” story, knew nothing about one of the most significant developments at that time. And it was from the Steels that the British Government got its news and formed its policies on Germany.

“Well, I knew nothing about this,” he said lamely, when I had convinced him that things were as I had described them. “I must say, I wish these people would keep me informed.” There were other important occasions in which I found “these people” appeared not to have kept Mr. Steel informed, and that after he had replaced Sir William Strang as political adviser. But that is another story to be related in its due place.

Before long the wreckers had switched their propaganda line from the “Impenetrable Soviet Zone” to the “Soviet Zone of Mystery.” What is the good of us sending teams into a few factories which the Russians select themselves to inspect demilitarisation? What’s the good of blowing up air-fields and bunkers when for instance shipyards aren’t included in the lists? What do we know about what the Russians are building at Rostock on the Baltic?

Stories began appearing in the West Berlin press and from there in the world press that the Russians had revived the shipbuilding yards at Rostock, were building naval vessels and submarines there. The Peenemunde stories cropped up at that time; the Russians were building V weapons again, which were being regularly tested and fired over the coast of Sweden. What’s the good of destroying airfields when research plants are not even included in the Control Council Agreement?

Such was the new propaganda line developed because the West had become so sensitive to Russian criticism of the failure to demilitarise which only came to light when the zones were thrown open to the joint inspection teams.

The wreckers hoped to scare the Russians off any wider demilitarisation agreement and by pressing their points, they hoped to get the Russians to withdraw from what had already been agreed. But the Russians called their bluff. They proposed that shipbuilding installations should be included and invited Allied teams to visit Rostock and see for themselves what was going on. They also intimated that they were anxious to have an agreement which would include every type of research installation. And this threw the wreckers into a panic. They really believed some of their own propaganda and thought the Russians were doing the same things in their zone as was being done in the west, stalling on some of the most vital aspects of demilitarisation. The inspection teams by this time had finished their work in the Soviet Zone and they had reported that the Russians had loyally carried out their task under the December 30 agreement.

Work in the British Zone had hardly started. Officials whom I interviewed on the subject said: “The Russians have every right to complain. But we just can’t get the manpower, you know.”

An Air Force Intelligence Officer, who visited me to see my photographs of the Russian demolitions at Peenemunde, said: “I don’t wonder the Russians complain that we are only playing at demolitions. This stuff makes our work look silly.”

At all costs the mutual inspection of demolition of shipbuilding facilities had to be stopped. Everybody knew that they had been preserved substantially intact in the British Zone. Potsdam said: “The production of ... seagoing ships shall be prohibited and prevented,” but the Germany First group, who were running Military Government, had other plans.

They were determined that Germany should be allowed to build ships – as she is now doing, ocean-goers up to 7,000 tons – and so the installations had to be saved. The Forrestal-Royall-Draper school were already well away by this time with their scheme to revive Germany as the base for the next war against the Soviet Union.

A new line of propaganda was fed to the press. “What’s the good of all this dismantling and destruction unless we are allowed to know exactly what goes on in the Soviet Zone. Military installations are not the most important war potential, industry itself is. Unless the Russians throw every square yard of their zone open, allow our teams to go where they like when they like; to inspect every plant at any time, no matter what it is making, we won’t have any more Soviet representatives roaming around in our zones.

After that, the Russians no longer believed the western powers were sincere in wanting to demolish military installations. They recognised it for what it was, the old game of stalling, playing for time, talking about destruction of war potential but not destroying it. They wanted some evidence of sincerity, but got hypocritical demagogy instead. Once again the deliberate policy of wrecking four-power unity.

Had the western powers really believed their own propaganda about tanks, planes and warships being manufactured in the Soviet Zone, they would have eagerly taken the chance to inspect

(a) all the plants listed by combined intelligence in the Soviet Zone;

(b) every shipbuilding installation, and

(c) all research institutes.

They could have carried out a step-by-step, planned programme to have effected this. They had no grounds for complaints, if they were sincere in wanting to de-militarise. They were the ones who named the plants the Russians were to inspect in their own zones. The Russians had no more freedom to roam in the western zones than did the western representatives in the Soviet Zone. And they did not ask for any privileges they were not prepared to extend to the West.

Even had the western powers sincerely believed that tanks and planes were being built in textile factories in Saxony, they would at least have seized the opportunity offered of checking on what they could. But they did not want such an agreement. They feared such an agreement. They could not offer reciprocal facilities in their own zones without disclosing how miserably they had failed to carry out their obligations.

Lest there should be any doubt about this, we have a statement provoked by a guilty conscience from no less an authority than Mr. Bevin himself, during a House of Commons debate on Germany on Thursday, July 22, 1949.

Bevin was defending himself from Tory attacks on his dismantling policy in Germany.

“I made a promise in Moscow,” said Mr. Bevin, “I think this is where the Russians have a grievance. I said I would complete the dismantling of what were called Number 1 war plants, by June, 1948. I tried my best but I was completely hampered by the Allies.”

“By whom?” from a questioner.

“The Americans took one view at one time and then altered it and put up entirely different proposals. I doubt,” he continued, repeating a lesson which had been drummed into him in Washington by the Clay-Draper school of anti-dismantlers, “if dismantling is any good except the plants which must be destroyed for security.”

Perhaps some tremor of fear, caused by the knowledge of how far he had committed England to America’s future plans for Germany, crossed Mr. Bevin’s mind at this point, for he added: “It is all very well to write Germany off as never being a potential aggressor. I am not ready to do that yet. Nobody with responsibility in the Foreign Office is prepared to do it either.”

Socialisation was abandoned by Mr. Bevin on his own admission because of American pressure, demilitarisation was abandoned by Mr. Bevin on his own admission because of American pressure. The Bevin’s statement incidentally removes the last chance of an excuse for the actions of his representatives in Germany in stalling on the work of the inspection teams. The Agreement made by Mr. Bevin was a concrete one about Number 1 war plants, named and listed. There was no mention in that agreement of even research institutes, let alone ordinary industries. The Russians were pressing for inspection of the demolition of those specific plants which Mr. Bevin had promised would be destroyed.

The myth that the Soviet Zone was sheltered from the Allies by an “iron curtain” is one which was carefully cultivated but which had no foundation in fact. It was widely believed abroad that the Allies had no access whatsoever to the Soviet Zone, that we have no information as to what is happening there, except such as comes to us from “refugees.”

Actually the Allies have maintained Military Missions to the Soviet Zone, stationed at Potsdam from the first days of occupation. Long after the Control Council crisis and the blockade difficulties, I know that Brigadier Curtis, head of the British Military Mission, was free to travel about the Soviet Zone and check up on reports of military activity. The last time I saw him, late in 1948, he had just come back from some remote spot, where Germans had reported an armored train, complete with guns, headed “in the direction of Moscow.” (Obviously just turned out of some secret plant camouflaged as a stocking factory.) Curtis found that there was an armored train there, sure enough, but completely wrecked and with the breech of every gun burst open by Soviet demolition squads.

Brig. Curtis assured me that every facility was given him to carry on his work in the Soviet Zone.

0n October 22, 1946, Mr. Bevin told the British House of Commons that it had been decided to socialise the Ruhr heavy industry. As a first step, the steel and coal industries would be socialised, later chemical and engineering industries. For the time being, British control officials had been put in charge but these would soon be replaced by German trustees for a future German government.

Earlier, on August 20, 1946, Air Marshal Sir Sholto Douglas, then British Military Governor, announced to the Control Council that he had taken over all iron and steel plants in the British Zone. The object, he said, was to break up the concentration of power formerly in the hands of United Steel, to reduce the capacity of the industry to peace-time needs, to prepare the industry for reorganisation. The industries, he promised, would never be returned to their former owners.

In Berlin, we were told that the socialisation scheme had nothing to do with politics or the fact that there was a socialist government in Britain. It had been proposed in fact by the military men, purely as a security measure. It was felt, we were told, that the only way to ensure disarmament of a future Germany was to control the industrial heart of the country, and the easiest way to do that would be to have the heavy industries run by a German government over which the Allies must maintain some sort of permanent inspectorate. One could call a government to account for breaches of agreement more easily than private firms, so ran the argument.

Mr. Bevin returned to the subject several times, as also did lesser lights in the government and the Control Commission. There could be no doubts that the British Government was pledged to socialise the key German industries.

From the very first these proposals brought forth protests from the Americans. Was not socialism the same as Nazism? Wasn’t it National Socialism that we had been fighting and were pledged to destroy in Germany? Would the Ruhr industry be less dangerous in the hands of a strong German government than in the hands of private owners? What was socialised industry but a gigantic cartel – and were we not pledged to destroy cartels? A state-owned industry was the monopoly to beat all monopolies, the most dangerous form of all. Such were the arguments used by the uniformed representatives of the American trusts at U.S. Military Government headquarters.

The trump American argument, however, was a “moral” one. We are here to teach the Germans democracy, aren’t we? How can you British be so wicked as to want to force the Germans into socialism? Let the German people themselves decide what should be done with their industries; let them decide for socialism or free enterprise. And gradually the British knuckled under to these arguments. The top men in the Control Commission never wanted it anyway. In effect they struck a bargain with Clay in the very early days, when Clay was supporting the decartelisation law. “You call off decartelisation,” they said, “and we’ll call off socialisation.” That’s the way it worked out, even if the bargain was not as precisely phrased as that.

There were some British officials in the field who put up a fight for the government policy of socialisation. One of them was a British trade union official, Alan Flanders, head of the German section of political division. He persuaded his chief, Christian Steel, that the British were on safe grounds and could meet the German objections because all the leading political parties in the British Zone had expressed themselves in favour of socialisation.

The Social Democrats and Christian Democrats had both passed resolutions to this effect. The Communists, naturally, had been demanding socialisation from the first. Only the minority party, Free Democrats, Liberal Democrats and small right wing groups were against it. Tell the Americans the Germans themselves are demanding socialisation, he said.

That was not enough for Steel, however. Flanders was sent down to tour the British Zone and obtain declarations from the various party leaders that they were in favour of turning the Ruhr industry over to public ownership. He had no difficulties with the Social Democrats and Communists.

Adenauer, however, who had been in the meantime in close contact with the Americans, chose the moment of Flander’s tour for a violent attack on socialisation. He demanded protection for private enterprise and help for German industry by investments from abroad, so that Germany could play her rightful role “in European recovery.”

The speech was contrary to a resolution passed by the Christian Democrats a few weeks earlier. It was hailed with delight by the Americans as proof of their contention that the Germans themselves were against socialisation. Flanders spent weeks in the Zone trying to force the Christian Democrats to repudiate Adenauer’s speech, or get him thrown out as leader of the party. There was a “leftist” section in the party at that time strongly opposed to Adenauer’s leadership, but the smell of American dollars was already becoming too strong in the Ruhr. The industrialists were beginning to emerge from their fur-lined hideouts to give money and instructions to the Christian Democrats.

Flanders failed in his mission and returned to Berlin. Shortly afterwards he was withdrawn from Germany altogether.

He was compensated for his graceful withdrawal from the fight for socialisation with an American scholarship which enabled him to go to the United States for a few months “to study trade unionism and social conditions.”

At the same time the only other Transport House (British Labour Party headquarters) nominee in a high political post, certainly the only other one who opposed Steel on the question of socialisation, Mr. Austin Albu, head of the Governmental Sub-Commission, was recalled to London. He was afterwards rewarded with a safe Labour seat in the House of Commons. Steel took over Albu’s job, or rather combined it with his own, and moved upstairs to be chief political adviser with the rank of ambassador. The career men had won out and sent the trade union officials scuttling back home.