MIA > Archive > Cliff > Obituaries etc.

Copied with thanks from the Counterfire Website, 8 April 2020.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Marxists’ Internet Archive.

|

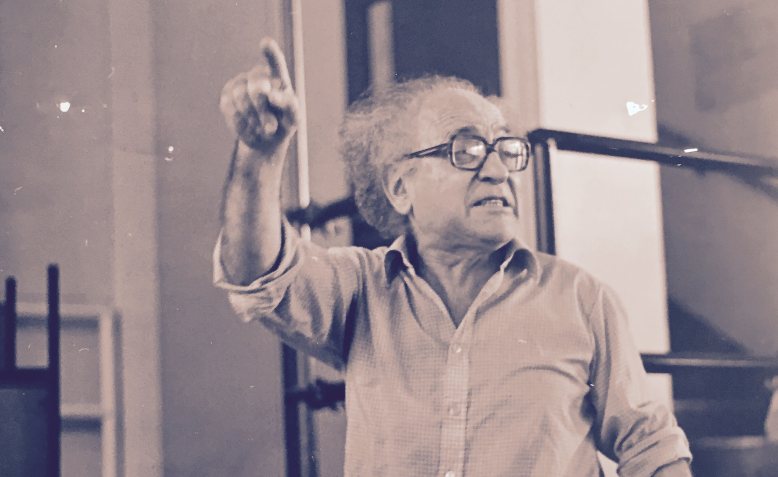

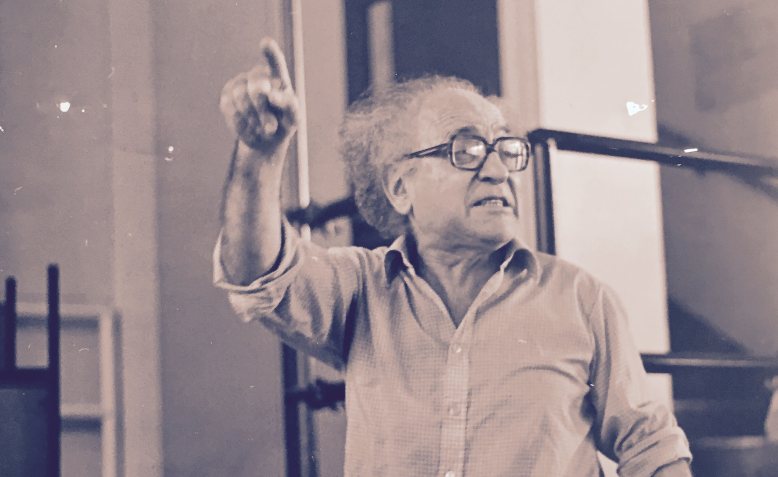

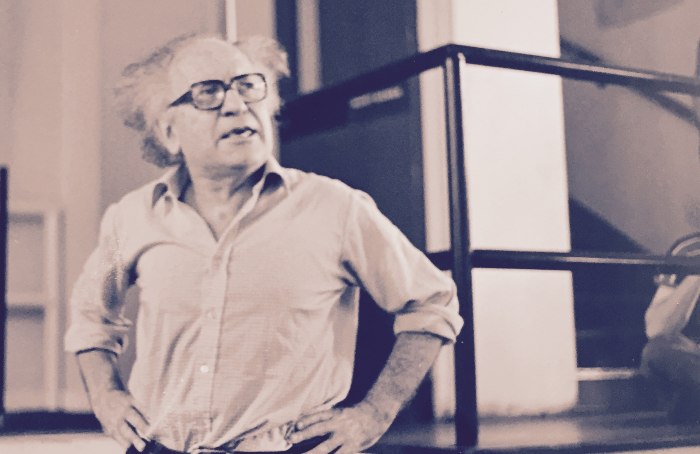

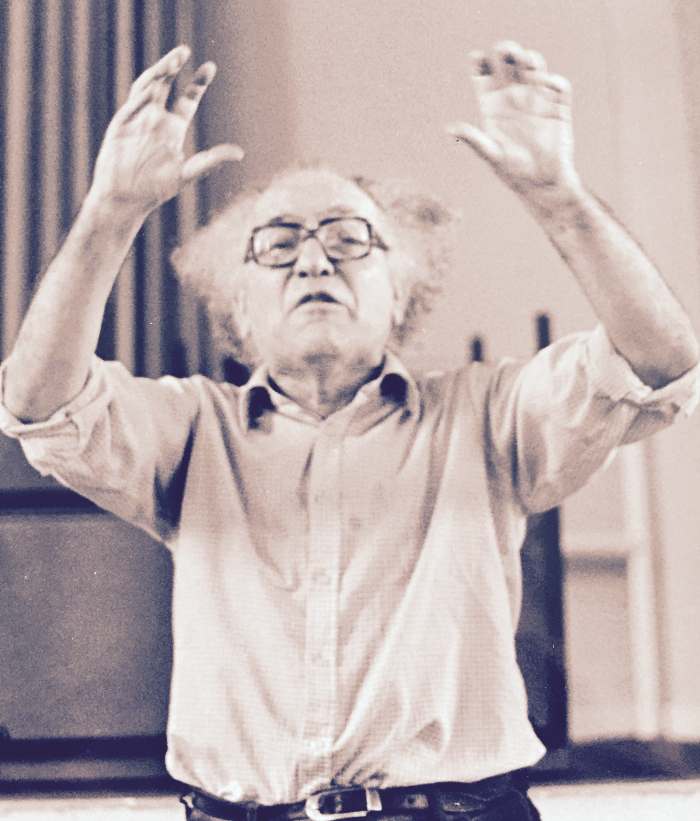

Tony Cliff died 20 years ago today. He was an extraordinary leader of the revolutionary left and during his lifetime the organisation that he founded, the International Socialists (which in 1977 became the Socialist Workers Party), was the most theoretically original and practically effective organisation on the far left.

I wrote about Cliff at the time of his death in 2000 and haven’t done so since. But the passage of time does reveal what is enduring. Here are some of the things that I remember from working with Cliff that made him such an effective revolutionary.

Cliff was personally one of the most straightforward people I have ever met. But it is not that kind of personal honesty that concerns me here. Cliff was an exponent of political honesty in the sense that he strove to express the truth as he saw it about any given situation without exaggeration, varnish, or evasion.

Cliff’s oft-repeated mantra was that ‘Communists never lie to the class’. But if you aren’t to lie to others you have first to be honest with yourself. This is harder than it might sound. For to be a revolutionary means to be part of an exploited and oppressed class. One is, therefore, in a relatively weak and powerless position. None of the levers of power, influence or prestige in the society are available to you.

And powerlessness breeds dishonesty. Cliff was fond of quoting Lord Acton’s famous dictum that ‘power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely’. But without fail he would add, ‘and absolute powerlessness corrupts absolutely’.

For revolutionaries, powerlessness can breed two forms of dishonesty: exaggerated optimism and exaggerated pessimism, unjustified elation or unjustified despair. As Cliff put it in his autobiography:

‘Revolutionaries need to tell the truth, good and bad, not only because not to do so cheats the workers they are addressing, but because they deceive themselves. Without an honest accounting it is impossible to orientate properly on a situation. A too pessimistic analysis can lead to passivity, an over-optimistic one leads to adventurism and in the long run to disappointment, which also leads to passivity.’

Cliff was a proponent of analysing every political situation with ruthless honesty because it was the only way in which it was possible to rule out both hopeless overconfidence and useless miserablism.

What remained was a precise account of where the strengths and weaknesses of the ruling class and the working class lay, and what practical steps could be taken to advance the struggle given the balance of forces at the time.

When in the 1950s and 1960s both Stalinism in the East and Western capitalism seemed immutable, Cliff developed analyses of both which did not seek to dismiss the fact of their stability but to explain it. The theory of the permanent arms economy detailed the roots of the stability of Western capitalism (and of reformism in the labour movement) while the theory of state capitalism provided a framework for understanding Stalinism. Relatedly, the theory of deflected permanent revolution sought to explain how the anti-colonial revolutions of the same era ended not in a socialist transformation, as Trotsky’s theory of permanent revolution had foreseen, but in independent states still subordinate to the world market. As Cliff wrote:

‘The troika – state capitalism, the permanent arms economy, and deflected permanent revolution – make a unity, a totality, grasping the changes in the situation of humanity after the Second World War. This is an affirmation of Trotskyism in general, while at the same time partially its negation. Marxism as a living theory must continue as it is, and change at the same time.’

These theoretical approaches explained that the world was composed of ultimately unstable systems that would eventually become crisis-ridden, but only over a timescale measured in decades. It was a remarkable act of theoretical honesty because it required exceptional patience, a commitment to long term theoretical propaganda as a principle form of activity, and a willingness to go against the stream of received opinion not only in society as a whole but on the left as well.

People who knew Cliff often used to say that he ‘had a nose for the class struggle’, that he could almost intuitively sense changes in the shape of working class struggle and the consciousness of working people.

In fact, Cliff was a very unlikely candidate for that kind of ‘intuition’. He was born to a middle class Zionist family in the district of Jerusalem in 1917 when Palestine was under British control. He became a socialist and was engaged in anti-war activity, arguing against support for the British during the Second World War. For this, he was imprisoned during the war and came to Britain, via Ireland, after the war. He never held a British passport and even after he spent time in Dublin and then settled in London he could never leave the country for fear of not being let back in. He was literally a stateless person.

Now, this is the kind of biography which might give you an intuitive knowledge of imperialism, but not of the working class, particularly the British working class.

Cliff attained that knowledge in two ways. Firstly, he was utterly committed theoretically to the Marxist proposition that capitalism is based on the exploitation and oppression of the working class and that working-class struggle is the most effective form of resistance to, and liberation from, capitalism. This required not just an abstract commitment to working-class struggle but a specific attempt to understand the concrete phases and forms of working-class struggle in any given period.

Secondly, Cliff listened closely to and studied obsessively what actual workers were saying and doing, especially but not only in the course of their trade union activity. He understood the workplace organisation and trade union structures of the British working class better than many very experienced native militants.

Perhaps the best-known product of this was the book on shop stewards and income policy, written with Colin Barker, which became a bestseller among trade union militants, quite an achievement for an immigrant Palestinian Jew with an idiosyncratic grasp of English!

|

Cliff was deeply immersed in the Marxist tradition. He had read extensively, perhaps completely, the works of Marx and Engels, Rosa Luxemburg, Lenin and Trotsky. But he had also read their theoretical antecedents. I once asked him, at a time when I was reading him for the first time, if he had read Hegel. ‘Yes, of course’, he replied, ‘I’ve read all of it, and I agree with it’. This was a Marxist joke of course, especially at a time when Hegel was again being treated as a dead dog by the then fashionable followers of French Stalinist philosopher Louis Althusser and assorted post-modernists. But it was also a profession of faith in the Hegelian Marxist tradition and an indication of how completely, from Goethe to Heine, Cliff understood that intellectual landscape.

Cliff was equally at home with the intricate detail of Marxist economics as anyone who has read his account of the accumulation of capital schemes in the full version of his work on Rosa Luxemburg can testify.

At the same time he had no time either for academic Marxism or for theory divorced from practice. Academic Marxism was for Cliff an oxymoron precisely because it lacked any relationship with political practice. He found Louis Althusser’s idea of ‘theoretical practice’, the notion that theory was its own form of practice, to be ridiculous to the point of laughable. Indeed one of his favourite jokes in this context was to parody this idea, ‘I write a book, that’s the theory. You read it, that’s the practice!’.

For every time that Cliff quoted Lenin to the effect that ‘there can be no revolutionary practice without revolutionary theory’ he would also quote ‘an ounce of practice is worth a ton of theory’. Marx’s 11th thesis on Feuerbach, that ‘philosophers have only interpreted the world, the point however is to change it’, was just as frequently quoted to the same purpose. These two epigrams existed in a dialectical tension for Cliff. No practice without theory, no theory without practice.

The need for clarity was at the heart of this dialectical relationship between theory and practice. For theory to grip the masses it must be expressed with great simplicity, but without oversimplification. I never heard Cliff refer to it but he was a great believer in the sentiment behind Albert Einstien’s view that you never understand a subject unless you can explain it to someone else.

For this reason, Cliff was a great inventor of epigrams and jokes. I’ve lost count of the times that, to demonstrate the foolishness of advancing the same slogan in changed circumstances, he would tell of the fiddler who came and played a beautiful wedding tune at a social gathering only to be beaten by the host. ‘Why are you beating me?’ he asks. ‘Because it’s a funeral’, his enraged antagonist replies. The fiddler returns the following week and plays a haunting funeral dirge, only to be beaten again. ‘You fool, it’s a wedding!’ cries his host. When someone Cliff regarded as habitually mistaken said something he agreed with he would say ‘even a blind hen can sometimes pick up a grain of corn’.

All theory was to be bent to answering a single question, What is to be Done? No matter how abstract theoretical work might necessarily be it was always ultimately meant to answer this question. Political organisation and political practice were the decisive moment where theory was proved right or wrong and where action based on theory could transform the world. Moreover, it was ultimately from political practice that new theoretical questions arose, practice being the ultimate source of, and result of, theory. Lenin took it from Goethe and Cliff took it from Lenin: ‘all theory my friend is grey, but green is the tree of life’.

And if political practice is the ultimate proving ground, and indeed the point of theory, then decisiveness and daring in practice are necessary.

Decisiveness is necessary because a correct strategy will be ineffective if not decisively implemented. Even an incorrect strategy can only be revealed as false if it is decisively implemented, otherwise it can never become clear whether the fault lies in the strategy itself or the indecisive implementation.

Daring is also a requirement of this approach. Every new strategy emerges from a previously existing practice which is rooted in a particular set of historical conditions. When those conditions change and a new practice is required then a break with the past is also required. And this in turn means the abandonment of cherished old slogans and modes of operation. This requires daring and a willingness to ‘bend the stick’, a favourite Cliff phrase, in order to break with the past and adopt new approaches and methods of organisation.

A similar approach lay behind Cliff’s continual insistence that socialists must identify and then seize hold of the ‘key link’ in any chain of political events. This idea, like much in Cliff’s arsenal, came from Lenin. In any political situation, Lenin argued, the myriad aspects which make it up are all connected, like the links in a chain. Whoever can identify the key link and seize hold of it would ‘guarantee it’s possessor the possession of the whole chain’.

So, for instance, in the early 1970s although the social crisis presented itself in many different struggles Cliff identified the industrial struggle as essential, and within that the role of shop stewards and rank and file organisation. The International Socialists did not ignore other struggles, from the rent strikes to the movement against the Vietnam War, but they did focus huge resources on the industrial struggle. And ultimately this was right. It was that struggle which drove Edward Heath’s Tory government from office and it was the ultimate defeat of that struggle which first paved the way for Thatcherism. Indeed the battle to destroy union militancy then defined the Thatcher project itself.

In other periods, like the era of defeat after the 1984-85 miners strike for instance, Cliff would put much weight on propagating the Marxist tradition and developing a stable routine of party activity that could carry an organisation of revolutionaries through difficult times where the possibility for agitation was much reduced.

Indeed, much of how Cliff looked at the possibilities for revolutionaries ran along the spectrum between agitation and propaganda. He many times repeated the definition made by Plekhanov, that agitation is a single idea before a mass audience and propaganda is a complex of ideas before a small audience. Of course a revolutionary party will always be involved in both, but given the nature of the period and the opportunities for struggle that it contains, the balance will be different. Finding the right balance between agitation and propaganda, and the right organisational methods of enacting such a strategy, is the essential task of revolutionaries.

|

As soon as the political situation changed in the late 1960s from the relative quietude of the long post-war boom to a period of more open struggles Cliff was perpetually looking for ways in which the small group of International Socialists (IS) could connect with the wider movement and find an audience for their ideas, or ‘create a periphery’ in a favourite Cliff expression.

In the 1960s they threw themselves into the movement against the Vietnam War. Cliff often used the infamous leaflet produced by the Workers Revolutionary Party to justify their failure to participate in the anti-war marches, entitled ‘Why We Are Not Marching’, as the last word in sectarian stupidity. But while the IS participated enthusiastically in the movement it did not fail to raise its own politics, specifically its state capitalist analysis of Russia and China. This was not always popular since China was the critical backer of the Vietnamese resistance and many both in the Communist and orthodox Trotskyist tradition were uncritical, or less critical, of those regimes.

This is always a difficult line to tread. Too much insistence on arguing your own position and too little stress on what unites you with others results in sectarian isolation. Too little instance on an independent Marxist analysis leads to accommodation with the ruling ideas in society and a failure to express and organise the most militant and effective sections of the class.

Cliff, typically, would express this in a story. In this case a story of a picket line. He would ask what do you do if you are on a picket line and one of your fellow pickets makes a racist remark? You can do three things, Cliff would say. You can walk off the picket line in disgust. But this weakens the picket and isolates you. That’s sectarian. Or you can whistle, talk about about the weather, and pretend that the racist remark hasn’t been made. That’s opportunism that allows racism to spread. The right thing to do is to argue with the racist, but when a scab lorry tries to break through the picket line you link arms with the racist to stop the scab. Thus you make a principled argument but not at the cost of weakening action against the main enemy, the ruling class (or scabs acting in the interests of the ruling class in this story).

All this was rooted in Trotsky’s writings on the fight against fascism in the 1930s. The failure to stop the rise of European fascism and the subsequent Holocaust were, of course, very deeply felt issues for Cliff. While young he had married a Jewish woman to prevent her becoming a victim of the Holocaust. Cliff’s opposition to racism and fascism was absolute and uncompromising. And the Anti-Nazi League, launched and sustained by the SWP, in response to the increased support for the fascists of the National Front in the 1970s, was an expression of this. It was modelled on exactly the principles that Trotsky had outlined in his writings on the United Front in the 1930s. In meeting after meeting, Cliff would repeat Trotsky’s parable of the cows being driven to the slaughterhouse, designed to counter the Stalinist ultra-leftism which decried any unity between revolutionaries and reformists, labelled ‘social fascists’ who, by defending capitalism, were as bad as the fascists themselves:

‘A cattle dealer once drove some bulls to the slaughterhouse. And the butcher came at night with his sharp knife. ”Let us close ranks and jack up this executioner on our horns,” suggested one of the bulls. “If you please, in what way is the butcher any worse than the dealer who drove us hither with his cudgel?” replied the bulls, who had received their political education in Manuilsky’s institute. [The Comintern.] “But we shall be able to attend to the dealer as well afterwards!” ”Nothing doing,” replied the bulls firm in their principles, to the counselor. “You are trying, from the left, to shield our enemies – you are a social-butcher yourself.” And they refused to close ranks.’

This united front approach, of which the Anti-Nazi League was the first modern embodiment, has served the British revolutionary left extraordinarily well. It informed the rank and file organisations that the IS launched in the 1970s, it was the thought behind the miners support groups that provided essential solidarity in the great strike of 1984–85, it was present in the Anti-Poll Tax movement launched mostly by the Militant in 1989, and it informed the Stop the War Coalition, the largest mass movement the UK has seen, and the People’s Assembly Against Austerity, initiated by Counterfire as the main labour movement response to the crash of 2008.

|

Cliff spent considerable theoretical and practical effort relating to issues of oppression, specifically analysing the relationship between class and oppression. Uniquely among the Trotskyist leaders of his generation, he wrote a book on Marxism and women’s liberation and a pamphlet on gay liberation, in addition to his constant work in fighting racism and fascism. The IS was unusual in launching specific publications aimed at Women and black people, respectively Women’s Voice and Flame.

Cliff’s work was concerned to articulate the ways in which class exploitation and oppression intersected with other forms of oppression. He was constantly concerned with how to articulate a class perspective within struggles against oppression, struggles which otherwise often could become dominated by middle-class leaderships, often reformist or separatist in their orientation. He was quick to see how the explosive struggles of the 1960s were co-opted from the late 1970s.

Of course Cliff always started from the proposition that ‘revolutionaries always side with the oppressed’. But that was the easy bit. And Cliff, equally frequently, insisted ‘there is no natural unity among the oppressed’. And to hammer home this difficult truth he would, with a mischievous glint of the eye, ask, ‘you do know that some Nazis were gay?’. His point was very serious and important: being a member of an oppressed group is no guarantee of holding progressive political positions. Neither is it any guarantee that solidarity with other oppressed groups is automatic. It is quite possible to be oppressed and to hold reactionary views about other oppressed groups. This is also true of working-class people of course. But unlike class exploitation, there is no structure in society which brings all the oppressed together and subjects them to a common regime of oppression which can become the arena for collective struggle. Among the oppressed, collective responses can be fashioned, but they have to be consciously constructed without the substratum of collective experience which underlies working-class life.

Since Cliff’s death both the fissiparous nature of political movements against oppression, and degree to which the language of identity politics and multiculturalism have been adopted by the state and its apparatuses, underline how prescient his approach has turned out to be. As the turn to intersectionality proves, however partially and inadequately, the existing models of fighting oppression have left the working-class oppressed struggling at the bottom of society while a small minority of the middle-class oppressed have levered themselves into the system.

Underlying everything Cliff did or wrote was one overwhelmingly important idea: an organisation of revolutionaries must be built. The working-class movement has developed no better model for increasing its ability to confront and ultimately transform the capitalist system.

As usual, Cliff had a story to illustrate why a revolutionary party was necessary. As usual, it was based on the classical Marxist tradition. In this case Cliff claimed it was based on an incident described by Trotsky in his autobiography My Life. I’ve since looked this up. There is something there but it’s not in the kind of Aesopian form that it assumes in Cliff’s rendition. But Cliff’s version has much more explanatory force. So here it is, from memory:

‘Trotsky says that the first five workers that he ever met taught him all he needed to know about revolutionary organisation. One was an utter reactionary. A racist, a sexist, and a scab. If he died and went to hell and there was a picket line on the gates of hell, he’d scab on that. Utterly immovable this side of a revolution. Then there was another one of the five workers who was a revolutionary, a good militant and would always stand up for the oppressed. The three other workers were in the middle. They would sometimes side with the revolutionary, and sometimes with the scab. The point of revolutionary organisation is to group the one in five revolutionaries together, give them the means to co-operate, develop the arguments that are most effective, and allow them to win over the three workers in the middle, and isolate and defeat the reactionaries.’

This is of course a simplified model of a vanguard party. It depends on organising the militant minority as a lever which can unite and lead the majority of the class against their exploiters and oppressors, and in so doing marginalise those who support them in the working class.

It is the opposite of the Labour Party or social-democratic model of the party. In this model, the party tries to organise the whole class from the most militant to the most reactionary in order to get them to vote for them in an election. The result is inevitably compromise with the system, because it is an approach which rather than seek to lead struggles that can transform working-class consciousness, it accepts the spectrum of working-class consciousness as it currently exists.

But working-class consciousness as it exists is shaped by the feeling of powerlessness that exploitation induces and by the mass media, the education system, and the institutions of the state which batten on to feelings of weakness and insecurity in order to tie people to the system. Any organisation which seeks to reflect the views of workers as they are will only partially express the view that a different society is necessary, and mostly express compromise with the system.

Worse than this the leadership of reformist organisation, most of the time, institutionalises compromise and actively opposes militant opposition to the system. This is why revolutionaries must organise the militant minority in an independent organisation.

Cliff and Gluckstein’s history of the Labour Party and their book of the trade unions underlined these facts. But even more than that his life’s work was to create a fighting organisation of working-class militants, theoretically informed, strategically sophisticated, and capable of shaping the class struggle in ways which were both effective in the here and now and which could lead working people towards being able to end a system which subordinated their lives to the pursuit of profit.

Cliff would not have been surprised that the path has been different than he might have expected. He often said that ‘Marxism is not a crystal ball’. Neither would he have been daunted that the far left is more fragmented than in the past. Indeed, he never paid very much attention to the sectarian left. He took the view that the ideas worth debating were those that held sway over significant groups of workers. Ideas that did not were not worth much attention. He often said ‘if you want to survive on the left you need to ignore a lot of the left’. When he came across a comrade reading the sectarian press he would laugh and say ‘why torment yourself?’

Neither was Cliff worried about being small in number, though he fought tenaciously to make sure the numbers of organised revolutionaries was as large as it could be in any given period. He thought political clarity and a correct strategic orientation were the essential starting point. Without them numbers were useless.

The task Cliff set himself was to understand the shape of contemporary capitalism and to build an organisation of revolutionaries capable of leading struggles by uniting as many workers as possible on the most pressing issues of the day. He used to say that the most important aspect of any struggle was not the immediate gain but the spiritual growth of those involved. Their increase in confidence and combativity was what would carry them forward to challenge the whole of the existing society, it was a revolutionary transformation of consciousness in rehearsal. And that was what mattered.

Last updated on 19 April 2020