(Sub-heads added by Editors)

The reality of Canada as featherweight in the scale of imperialist countriesThe key issue at dispute, we said in Bulletin No. 25, is whether capitalist-imperialist Canada is becoming economically integrated with the capitalist-imperialist United States of America. We answered yes—Canada is past the point of no return in the process of economic integration with the US. We passed no moral judgment—we projected no program to either aid or deter this process—integration is an objective fact.

Although Canada has many of the characteristics of a colony or a semi-colony of the United States, it is neither. That is why we said in our statement of last November 14, 1972 (Bulletin 18) page 16, a thumb nail sketch of our position, that “we do not consider that this fact projects any general national tasks, with respect to English Canada, alliances of any kind with the Canadian capitalist class or any part of them (the enemy in our own country).”

Canada is economically integrated with the United States of America. While it retains a separate identity from the US as an independent nation -state (and is not likely to disappear as such prior to the socialist revolution) in many ways this is a facade. Canada is in a sense a 51st state in the capitalist United States of North America.

We will take up in detail in a further contribution what this means for our revolutionary socialist theory, and what effect it has on our revolutionary practice, for instance its effects on the dynamics of the Canadian class struggle, on the subjective factor, on the mentality of the Canadian masses, the arena of our politics.

The document Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism poses the question of Canadian integration very clearly in point 14. After all, it is everywhere in the air. Further integration was even one of the three options that Canada’ s Minister of External Affairs, Mitchell Sharp, discussed in a widely circulated statement that appeared in that department’s officia1 journal last fall. Both Mr. Sharp and Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism posed it as a matter of choice before the Canadian ruling class. The latter evaded a straight answer to the question whether Canada is becoming economically integrated with the US with the naive comment “Canadian capitalism (sic) can’t solve this contradiction.”

Elsewhere, however; Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism does answer this question—particularly in section 13. Its answer is a clear NO! It says so by presenting that Canadian capitalist class as a powerful independent capitalist class in domination of the key sectors of the Canadian economy, in full control of its financial institutions (particularly the banks, firmly established in its “fortress state", and one of the major colonial imperialist powers in the world.

Today, faced, as it claims, with the loss of its privileged positions with the US, in an opening era of sharpening inter-imperialist rivalries, Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism projects the Canadian capitalist class as being capable, in time, when it is necessary, of completely reorienting the Canadian economy away from the US, towards closer ties with other imperialist powers. With the firming up of the European Common Market, (Germany, France and Italy) and the blow that British association has dealt to the longstanding (previous Commonwealth -ed.) preferences Canada had with Great Britain, it would appear that Canada is left only to seriously court Japan—or the workers’ states.

Thus we have a Canada, cast by Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism in what might be called the classic mould of an imperialist-capitalist world power—not nearly so powerful as the United States, nor so powerful as West Germany or Japan, but somewhere on the same general level as Britain, France, or Italy—maybe a little higher or a little lower on the scale. Canada is to be understood, even with regards to its specific relations to the United States of America, much like France, Italy, Britain and their relations with the US colossus—they are also of course advanced capitalist nations and imperialist. We have even heard in our movement, in the hue and cry about Canadian nationalism, ominous hints of a future inter-imperialist war—a war between Canada and the United States of America.

This picture is at such complete variance with reality that we are compelled to take up in detail the sketchy economic data that Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism presents to uphold its thesis.

In Part I of this contribution we commenced this task with the presentation of some detailed information on a corporate giant said to be Canada’s largest private corporation in assets—the biggest single Canadian-owned monopoly—Bell (Canada). It is apparent that the listing of Bell as Canadian-owned, by the Grey Report upon which Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism leans heavily, is why the document can claim that foreign ownership in Canadian communications is a mere 0.4%. But whatever the dispersal of its shares Bell (Canada) is completely controlled by the 5th largest and most powerful corporation in the world—the US-owned American Telephone and Telegraph. It could be said of course that the Canadian state is firmly in control of Bell since by law, Bell, with its monopoly of Canadian communications, must apply for permission for rate increases, etc. The fact that it generally gets what it wants does not cause us to counter-claim that Bell controls the Canadian state. But the strength of Bell, the power and strategic position of US corporate interests in Canada, does clearly pose the question—who, or what alliance does control the Canadian state?

In Part 1 we also provided some detailed information on the Caribbean where “Canada has more trading investment interest... than in any other part of the underdeveloped world.” This information demonstrated that, aside from the holdings of Alcan which are by far the most profitable and strategic, Canadian interests are largely on the marginal areas of a declining economy. While listed as Canadian-owned Alcan is owned by the powerful US Mellon interests. Thus the Canadian state in its relations with the governments of the Caribbean, in effect, functions as a service agency for US imperialist interests which are growing in the Caribbean and are supplanting the longstanding Canadian private capital interests. The Canadian banks, as symbols of imperialist exploitation, received the wrath of the masses in recent protests that swept Trinidad, but the real power behind the scenes, was United States imperialism.

Our separate contribution on Canada’s financial institutions revealed that rather than serving as bulwarks in defence of private Canadian capital interests, as claimed by Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism, the banks have become instruments of the US takeover of the Canadian economy and, in the personnel of their boards of directors, are a microcosm of the integration of the Canadian and US ruling classes.

Our research on the banks, as limited as it was due both to lack of data and training, demolishes not only the contentions of Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism, but certain illusions held both by Quebec and by Anglo-Canadian nationalists and others.

The Confederation of National Trade Unions (CSN/CNTU) document It’s Up To Us, recognizes that “the Canadian banks and brokerage houses speeded up the American imperialist takeover of the country.” It notes also, together with their domination of the exploitation of Quebec’s vast natural resources, that “foreign monopolies in Quebec (primarily American)control 41.8 per cent of value-added in Quebec’s manufacturing process, while Anglo-Canadian and French-Canadian companies control 42.8 per cent.” But it erroneously contends that “the finance and banking sector today is relatively free of American or foreign interests.”

Canadian bourgeois nationalist, Abraham Rotstein, appealed to the Waffle (a large and influential left nationalist tendency based in English Canada -ed.) in the NDP (New Democratic Party, Canada’s labor party) (1970) to dump its concept that the struggle for an independent Canada is a class and socialist struggle, for his own “two stage approach” of mobilizing “all classes” in order to be successful. He warned Waffle that seeking “to nationalize the ‘commanding heights’ of the economy, for example in banking and finance, is to take on the opposition of the strongest remaining sector of the Canadian bourgeoisie.”

With this contribution we will show that the situation with Bell (Canada) and Canadian imperialist holdings in the Caribbean is in no way exceptional. On the contrary, while only in part, they quite accurately portray the real relations of capitalist-imperialist Canada with the United States.

We would first take up the question of Canada as an imperialist power—“one of the major colonialist imperialist powers in the world,” according to the document Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism.

Elsewhere it states, “Externally, Canadian capitalists have large substantial holdings rising with particular rapidity in Western Europe and in the semi-colonial world. Super exploitation of colonial peoples is a significant factor in Canadian bourgeois power.”

And, “Canadian capitalists have substantial foreign imperialist holdings. In 1967 (latest statistics available) Canadian direct investment abroad in branch plants, subsidiaries and controlled companies amounted to $4,030 billion—having more than doubled during the preceding decade” (this figure is of course in error. If it were a true figure Canada would be the super imperialist power of all times. It is exact1y 1,000 times smaller. The true figure is not four trillion or four thousand and thirty billion, but slightly more than four billion or four thousand and thirty million).

And, “While more than half of this foreign investment is in the U.S., the proportion of Canadian investment in the US is dropping steadily as Canadian investments elsewhere rise. Canada has foreign holdings spread over 32 countries, many of them in the semi-colonialist ‘third world’.”

These latter two points are embellished with a somewhat ingenuous statement of the type: pretty hefty isn’t he—particularly when you consider after all he isn’t an elephant but just a mouse; “Canadian corporate investment abroad bulks roughly as large in relation to the size of the Canadian economy, as US foreign investment in relation to the US economy.”

There are some real problems in coming to grips with, in getting a true picture of what actually are foreign investments of private Canadian capital—investments that can really be said to be Canadian—capital that is subject in some way to the authority of the Canadian capitalist class as a whole through the Canadian state—that the Canadian state is in a position or could conceive of itself to be in a position to direct.

The Liberian flag on the mast of a merchant ship has come to be known as a flag of convenience. The fleet flying the flag of tiny, almost landlocked, impoverished Liberia is the world’s largest, larger than Japan’s, almost double Britain’s and almost triple the US’s. Everyone who needs to know, accepts the Liberian flag as a legal fiction covering up the real ownership. Likewise much of what is called Canadian direct investment abroad is flying a flag of convenience—the Canadian flag is designed to cover over it’s US reality.

As our analysis of Canadian investment in the West Indies showed when you subtract the US-owned Alcan from the so-called Canadian investment you cut it almost in one half—down to $240 million—and almost half of that again was in mortgages, government securities, loans and other assets held by banking and insurance companies. Canadian investment turned out to be quite small and on the margins of the economy, non-strategic and non-growth. According to the same source used by the authors of Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism direct investment there stood in 1967 at $185 million.

If there had been foreign military intervention against the militant upsurge that swept Trinidad a few years ago—if it had been Canadian armed forces (already heavily committed to world capitalism’s interests in the Middle East, in Cyprus, in West Germany) they would have served primarily US imperialist interests. As it happened it was actually US military forces that appeared on the horizon of Trinidad. That is why we ended off Part 1 of this document with the observation that we are compelled to make a very critical investigation to ascertain the truth about private Canadian long term direct investment and portfolio investment abroad, to ascertain if it really is ‘Canadian,’ that it really is controlled by private Canadian capital and subject in some way to control by the Canadian nation-state.

Let us start with the few facts as are presented by Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism—the fact of “Canadian direct investment abroad of $4.03 billion—having more than doubled during the preceding decade.” This is culled from the Department of Industry, Trade and Commerce release on Direct Investment Abroad by Canada 1946-67, February, 1971.

Just five paragraphs farther down, in the introductory summary containing the above data, but apparently overlooked by the authors of Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism, we note the following: “non-residents (of Canada) control a substantial amount of Canadian direct investment abroad through ownership of Canadian corporations which have subsidiaries or branches abroad.” In other words, a “substantial amount” of these investments cannot in any way be said to be Canadian but are primarily US imperialist holdings with a Canadian cover.

And then there is the last sentence in this introductory summary. It reads, “At the end of 1967 the non-resident equity in Canadian direct investment abroad amounted to $l.7 billion, or 42.5 per cent of the total of $4.03 billion.” Thus it turns out—only 57.5 percent of the figure $4.03 billion worth of investment, brought to our attention by the authors of Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism, actually $2.33 billion—is controlled by “residents of Canada.” This statement was also somehow overlooked. We should add—the term used in the government release “resident of Canada” is a cautioning one, for investment can be resident in Canada and yet by no means be private Canadian capital. The corporation is merely domiciled for tax purposes in Canada. We will have more to say about this when we deal with US investments in Canada.

The high US component in what is called Canadian direct investment abroad, a matter of considerable relevancy to a document dealing with Canadian imperialism, its role in the world imperialist system and its relations with US imperialism, is further revealed, although less directly, in the same government bulletin. It notes that Canadian direct investment abroad up until 1946 stood at the relatively small figure of $772 million. But by 1967 it had undergone a tremendous growth—it increased by more than five times.

This is the same period when US capital was flooding into Canada, taking over already established corporations, buying into others, setting up branch plants, etc., etc. The relation between the US takeover of the commanding heights of the Canadian economy and the meteoric rise of Canadian direct investment abroad is obvious.

The government bulletin further notes that, “In 1963 some 59 enterprises, each with direct investments outside Canada of $5 million or more, accounted for $2,779 million. This was 89% of all direct investments abroad.”

The bulletin does not name any of the 59 corporations that would have foreign investments of $5 million or more. However the Financial Post list of the 100 largest manufacturing resources and utility companies in Canada, based on 1971 year-end figures, gives us some insight. They are ranked on the basis of sales—it also lists the assets of all but two. The 98th on the list by assets had slightly more than $12 million. As we shall show in the next section of this document, it is the US corporate giants that dominate the Canadian economy and there can be no question that the overwhelming majority of the 59 corporations that have more than $5 million invested outside Canada and account for 89% of Canadian direct investment abroad are not Canadian but US-owned or US-controlled.

Besides the few comments on the actual control of Canadian investments abroad which we have discussed above, gleaned from the summary “Introduction” of the government brochure, there is a separate section on “Country of Control.” It is here that we come across the information presented in Canada and the Crisis of Wor1d Imperialism to the effect that the book value of Canadian direct investment more than doubled in the period 1954-64. Unfortunately no effort is made to explain this. However this section provides us with other valuable information on the matter of control of Canadian investment abroad.

During this period (1954-64) when Canadian direct investment abroad more than doubled, “there was an increase of only 61.8 per cent in direct investment abroad by those corporations and other investors resident in Canada which were themselves either independent or under the control of other Canadians. On the other hand, “Direct ìnvestment by corporations and other investors resident in Canada but controlled from the United States increased by 217.5%, from $425 million to $l,307 million.”

As a result, the government brochure reads, “the proportion of Canadian direct investment abroad that was actually controlled in Canada decreased from 73% in 1954 to 57% in 1964... that (proportion) controlled from the U.S. rose from 26.3% to 38.9%....”

On of the reasons, according to the government brochure, was that non-resident control of the Canadian economy itself was growing during that period and in the same general areas that Canadian direct investment abroad was mainly directed. “Whatever the reason,” it notes, “it is clear that even in the field of Canadian investment abroad, Canadian control was declining.” The explanation—missing in Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism—is indeed damaging to the author’s theses.

Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism tells of the scaling down of Canadian investments in the US and its rise elsewhere; the wide dispersal of Canadian external holdings “spread over 32 countries, many of them in the semi-colonialist ‘third world’....” It notes the “particular rapidity” of the rise of Canadian capitalism’s holdings ``in the semi-colonial world... super-exploitation of colonial peoples is a significant factor in Canadian bourgeois power.”

This is not at all an accurate picture of Canadian direct investment abroad, neither where it is now concentrated, nor its dynamic, nor its direction. In fact the truth is quite the opposite, particularly in relation to private Canadian capital.

To be sure, it is spread over 32 countries but it is concentrated, and heavily concentrated, in the most developed sectors of the world economy where, incidently, there is not the slightest question as to who controls the economy and the state.

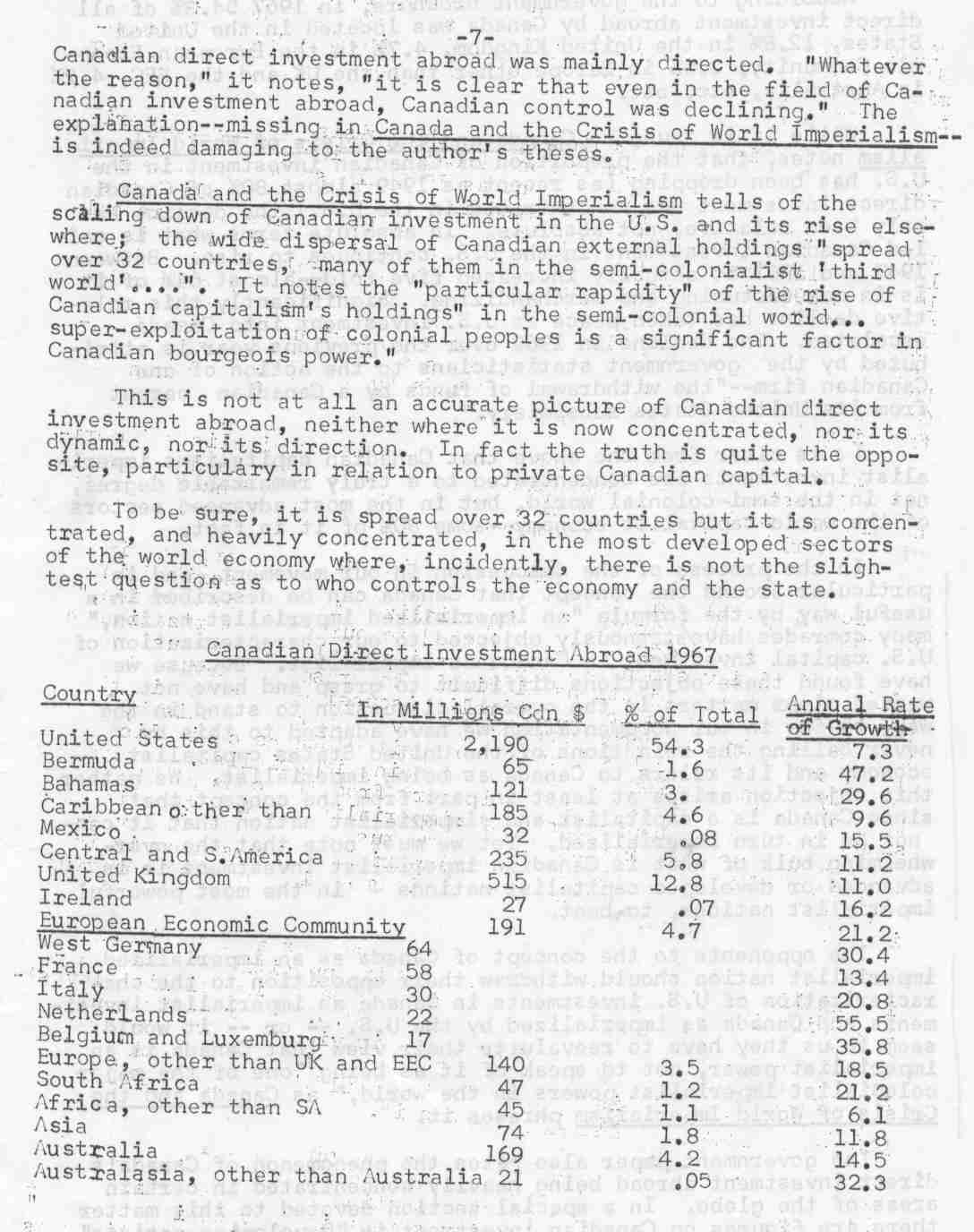

According to the government brochure, in 1967 54.3% of all direct investment abroad by Canada was located in the United States, l2.8% in the United Kingdom, 4.7% in the European Economic Community, 3.5% in Europe other than the UK and the EEC, 4.2% in Australia, etc., etc.

Whi1e it is true, as Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism notes, that the proportion of Canadian investment in the US has been dropping (as recent as 1949 almost 80% of Canadian direct investment was concentrated in the US) the decline has only been relative, not absolute. In absolute terms what is called Canadian investment in the US continues to rise. Between 1947 and 1967 it actually increased five-fold—almost 64% of it is in manufacturing and merchandizing. Significantly this relative decline has taken place as US investment into Canada escalated. The decline in 1962 over the previous year is attributed by the government statisticians to the action of one Canadian firm—“the withdrawal of funds by a Canadian parent from its United States subsidiary.”

It is clear from the above that Canadian capitalism’s imperialist investments are concentrated to a truly remarkable degree, not in the semi-colonial world, but in the most advanced sectors of the world capita1ist economy—some 80% of it in fact.

In the process of the discussion in our movement, and in particular around the concept that Canada can be described in a useful way by the formula “an imperialized imperialist nation,” many comrades have strenous1y objected to our characterization of US capital investment in Canada as imperialist. Because we have found these objections difficult to grasp and have not wanted minor matters in the overall discussion to stand in the way, so far in our documentation we have adapted to this by never calling the relations of the United States capitalist economy and its rulers to Canada as being imperialist. We gather this objection arises at least in part from the concept that since Canada is a capitalist and imperialist nation that it cannot be in turn imperialized. Yet we must note that the overwhelming bulk of what is Canadian imperialist investment is in advanced or developed capitalist nations—in the most powerful imperialist nations, to boot.

The opponents to the concept of Canada as an imperialized imperialist nation should withdraw their opposition to the characterization of US investments in Canada as imperialist investments, and Canada as imperialized by the US—or—it would seem to us they have to reevaluate their view that Canada is an imperialist power, not to speak of it as being “one of the major colonialist imperialist powers in the world,” as Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism phrases it.

The government paper also notes the phenomenon of Canada’s direct investment abroad being heavily concentrated in certain areas of the globe. In a special section devoted to this matter there are figures on Canadian investment in “Developing nations” and in “Developed nations.” It defines the developed nations as encompassing all of Europe, except Greece and Spain, only Japan in Asia, only South Africa in Africa, only Australia and New Zealand in Australasia, and only the United States and Canada in the Americas.

According to their breakdown only 18.6% of all direct investment abroad by Canada, or less than $750 million, was invested in the “developing nations”—in the colonial or semi-colonial world.

In the United States, in the United Kingdom, in the European Economic Community and in the Commonwealth (Australia and New Zealand certainly), Canadian imperialist investment possesses no serious element of power. It is just good, safe, solid investment, trying to take a cut—and a relatively small one—of a developed capitalist market. The capitalist class of those countries are certainly not subject to the control, the dictates of any special private Canadian capitalist interests—Canadian bourgeois national interests.

As for Canadian imperialist investments elsewhere—in the colonial and semi-colonial world—it would appear to be so small, both in absolute terms and relative to the influence of other interests, that it also could not be considered to contain any serious elements of power for the Canadian nation state.

It should also be noted that the areas of Canadian direct investment which show the greatest growth rate are precisely those where there is the least possibility of developing any political leverage—the most phenomenal are Bermuda and the Bahamas which are little more than paradisiac tax evasion havens for Canadian and US business tycoons, and tourist atolls.

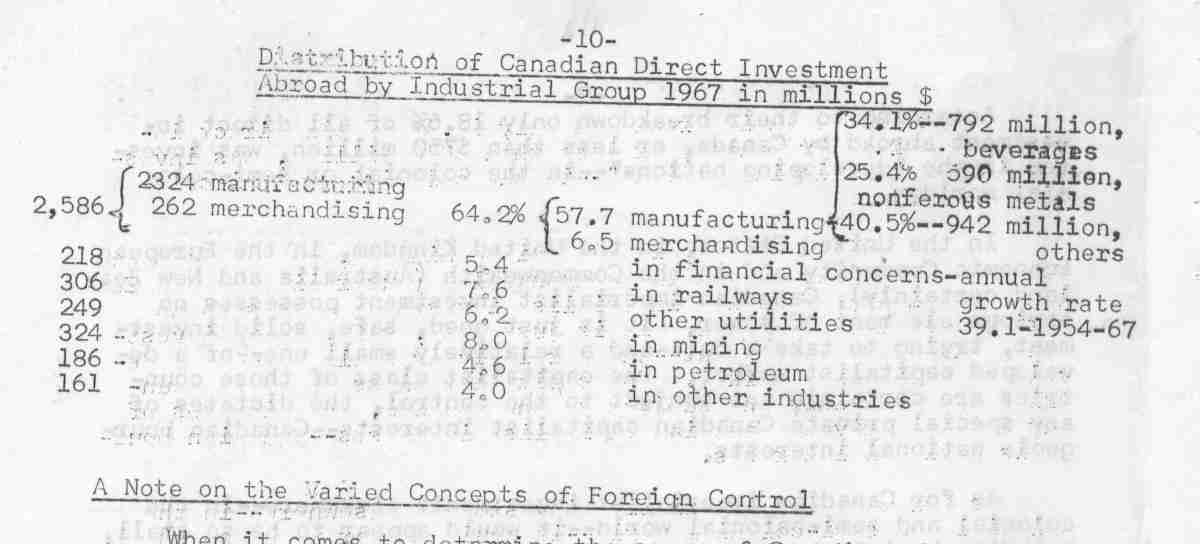

Aside from being very small and largely in advanced sectors of the globe with powerful, relatively stable regimes, the very nature of Canadian direct investment, that is, its composition, is of such a character as to give little political leverage to the Canadian state. It is not only concentrated in the most powerful imperialist nation states in the world, but it is concentrated in those sectors of their economy where they themselves are most efficient. Some 57.7% is in manufacturing and 6.5% is in merchandizing. Practically all of the direct Canadian investment in the United Kingdom (92.4%) falls into these two categories, and 63.9% in the United States is in the same categories. The third largest category (following mining at 8%) is railways. This $306 million investment is confined entirely within the borders of the United States of America.

When it comes to determine the scope of Canadian direct investment abroad, the Department of Industry, Trade and Commerce defines Canadian control "as said to exist if 50% of its voting stock is known to be held by residents of Canada. This can be modified by the addition or deletion, as appropriate, of concerns where it is believed that because of the distribution of the stock, either effective control is held with less than 50% of voting stock, or the holders of more than 50% are too scattered to exercise control (since complete knowledge of the share owners may not be available, the classification of borderline cases involves a measure of judgment based upon all the known factors which could be relevant). The concept of control which has been adopted is therefore, one of potential control through stock ownership."

It adds a note of caution with regards to the term “residents of Canada.” A company is resident in Canada if it is incorporated in Canada, regardless of its ownership. “Non-residents have a substantial equity in Canadian assets abroad through their ownership of a number of these firms resident in Canada which have subsidiaries or portfolio investment abroad,” it observes.

On January 25, 1973, Trade minister Gillespie, in presenting Ottawa’s plans for legislation on dealing with foreign investment, established quite different criteria when it comes to defining a foreign controlled company within Canada. He made the assurance to those whom it may concern, that the new legislation “is not to block foreign investment, but only to maximize Canadian advantage.” It was motivated by the government with the statement that it had concluded that the people felt “we had not gone far enough” with the first bill and that it had also taken note of Gallup Poll reports that 69% of Canadians favor a government agency to control new foreign investment. “The Canadian public have been ahead, generally speaking, of the politicians on this particular issue,” he said.

If 25% or more of the voting shares publicly traded are held by foreigners, the company will be assumed to be foreign-controlled.

The percentage for private companies will be 40%. Gillespie said that the process would not affect takeovers by Canadian citizens, by landed immigrants who have lived in Canada for six years or less or by firms they control.

The Gray Report, from which Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism draws its data, notes three different criteria for determining foreign ownership in Canada. In the Corporations and Labor Unions Returns Act (CALURA) series—“a company is considered foreign controlled if 50% or more of its voting stock is known to be held outside Canada, or by one or more Canadian companies which are in turn foreign controlled.”

The Industry Trade and Commerce guidelines—“a Canadian company is regarded as foreign controlled if 50% of its voting stock is owned by one foreign parent.”

The International Investment Position (IIP) compiled in the Balance of payments Section of the Dominion Bureau of Statistics defines “an enterprise is foreign controlled if 50% or more of its voting stock is held in one country outside of Canada. The enterprise includes all the corporations over which the foreign parent company or group of shareholders are in a position to exercise control.” The Gray Report statisticians favored the IIP criteria.

The Gray Report concentrated on foreign ownership, and foreign control in Canada. However it commented on Canadian direct investment abroad, in passing. According to Department of Industry, Trade and Commerce figures referred to earlier, in 1964, US control of what is called Canadian direct investment abroad was 40% of the total. The Gray Report notes, “According to DBS, Canadian direct investment abroad in 1964 totalled $3.5 billion. Non-residents controlled 47% of these investments (e.g. Ford’s subsidiary in South Africa). The 13 largest firms accounted for 70% of the total.”

Ford of Canada and its branch plants in South Africa, as a wholly-US-owned corporation, is easily separated out by DBS from the amount of Canadian direct investment abroad, as being “non-resident owned.” But what about Alcan? Inco? Massey Ferguson? Seagrams? Referring to large corporate entities headquartered in Canada and often identified as Canadian, the Gray Report states: “in some instances their Canadian identity becomes nominal, e.g. Inco and Massey Ferguson.” It further asks: “for example are Alcan and Seagrams really Canadian controlled?”

The holdings abroad of the two corporate giants, Alcan and International Nickel, would loom large in any case that would argue Canada as an imperialist “power"- particularly in the “super-exploitations of colonial peoples.”

From our calculations, we gather that Alcan’s investments in the West Indies were separated out from Canadian investment as being controlled by non-residents, by the Department of Industry, Trade and Commerce statisticians. Massey-Ferguson, Distillers Corporation, Seagrams, appear as having no foreign ownership in the Financial Post list of Canada’s 100 largest manufacturing, resource and utility companies. Alcan is 1isted as being 51.2% Canadian-owned and 39.4% US-owned; International Nickel as 50-50 Canadian-US-owned, at years end 1971.

In 1963, resident Canadian shareholding in Alcan was 24%—with 72% being held in the US. By 1970 it had risen to 40.6%, and early in November 1972 to 53.4%—the f1uctuations being between Canadian and US resident shareholding. The largest shareholder, with 3% of the stock, is the government of Norway.

As of 1970, 31% of Inco’s stock was Canadian resident-owned and about 56% US-owned. By August of 1972 Canadian resident ownership rose to 46.4% and US ownership dropped to 38.4%. It has been suggested that tax considerations which compel Canadian pension and retirement saving funds to seek investment in Canadian stocks account for the rise in Canadian ownership. In terms of control these changes in the common shares of Inco and Alcan no more make these giant Canadian-based corporations Canadian (each one of them with assets equal to the entire Canadian direct investment abroad) than Imperial 0i1’s recent highly publicized announcement that the company is managed by Canadians and has a Canadian-dominated board of directors.

In reality the Gray Report’s confusion as to whether Alcan, Inco, Massey-Ferguson are Canadian or US flows from the integration of the Canadian economy with that of the United States. If we must make a definition as Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism does, then we must say that its authors are dead wrong. We must say that, by every rational criteria, these imperialist holdings involved in the “super exploitation of colonial pop1es” are not private Canadian capital but are US imperialist-controlled—with a Canadian false front.

What are we to conclude with regards to Canadian imperialism from the above information? What does Canadian imperialism amount to, that is, as an extension abroad of the interests of private Canadian capital and the Canadian nation state?

As a leading trading nation, the composition of its exports, largely raw or semi-finished, directed large1y to the advanced capitalist world—almost entire1y to the US, along with the character of its imports—mostly finished goods, almost entirely from the US, give it a character much more similar to that of the under-developed countries than to the advanced capita1ist imperialist powers.

Its direct investments abroad are quite small—$2.33 billion, even accepting that open-ended formula “controlled by residents of Canada.” As a state, as a military power on its own, in the arena of inter-imperia1ist rivalries, Canada is incapable of defending itself, let alone its interests abroad against any but the weakest of its imperialist competitors. By no account can we say as does Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism that it is “one of the major colonial imperialist powers in the world.” Nor does it anywhere near meet the other qualities that Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism attributes to it.

As an imperialist power Canada can only be said to be significant on the world arena insofar as it is integrated with the US—insofar as its economic holdings and interests are inter-locked and find expression in harmony with those of the US imperialist colossus. Its intermediary, “honest broker” role between the world imperialist powers, its stooge role, primarily for US imperialism, including its recent initiatory feeler and face-saving gestures with China and the Soviet Union, is an accurate reflection of its real position as a capitalist power.

Canada is imperialist as two members of the Portuguese and South African Liberation Committee in Montreal recently described it—in its complicity with Portuguese imperialism—through membership with the US-dominated NATO military alliance, and “through the intervention of multi-national corporations implanted in both Canada and South Africa, such as Falconbridge Nickel, Alcan, Massey-Ferguson, Ford, Manufacturers Life, Sun Life, Weston, etc.”

Canada is imperialist by the fact that, with an advanced capitalist economy, it is an integral part of the world-wide imperialist economic system. It is imperialist through its much-heralded trade and aid agreements with the underdeveloped nations, with their tie-in to purchase Canadian goods and grant other concessions. It is imperialist as a supplier of $2.86 billion of materials to the (US-led imperialist ) assault on the Vietnamese revolution.

It is primarily through exposing Canada’s satellitic relation to the mightiest imperialist force in the world, and not through attempting to establish the “fact” of Canada’s imperialist holdings carrying out “super exploitation of colonial peoples,” that the real nature of Canadian imperialism is revealed.

The character of Canadian capitalism as an imperialist “power,” the locale and the nature of its investments abroad, the fact that it is only a world “power” as a front, or very junior partner, of the world’s super imperialist power—US capitalism, and thus constantly plays the role of running dog or craven apologist for US capitalism’s world-wide counter-revolutionary rote, is due not only to Canada’s relative weakness in relation to the US colossus (this inferiority it shares to varying degrees with all the capitalist powers). It is determined above all by the facts of US capitalism’s domination of Canadian capitalism, and of course Canadian society, within the borders of Canada itself.

Canada’s obsequious subservience to the US State department—Minister of External Affairs Sharp’s shameless admission that Canada was committed to the so-called peacekeeping mission in Vietnam by the US, without so much as a by your leave—Ottawa’s submission to the arrogant point by point instructions to its agent in Hanoi, is not a disease caught or passed on through breathing the air in its Ministry of Foreign Affairs. It is the facts of US capitalist domination over Canadian capitalism in Canada itself that determines Canada’s role. It is the imperialization of Canada itself.

From Canada as an imperialist power we will now proceed to deal with the economy in Canada itself, with the claim by the authors of Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism that “domination of key sectors of the economy” is in the hands of “private Canadian capital,” that the Canadian bourgeoisie “retains control over key sectors of the economy,” that the Canadian bourgeoisie, “powerful, cohesive, and highly monopolistic” is “in full control… of the Canadian economy,” that the Canadian bourgeoisie’s holdings in Canada “are not marginal, but located in the most profitable sectors of the economy,” etc, etc. And we will see what validity there is to our contention that the Canadian economy is integrated with that of the United States—and that in view of the crushing weight of United States capitalism the situation must be said to be quite the opposite to how Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism portrays it.

Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism devotes only 6 or 7 lines to the facts of US ownership in the Canadian economy, on the basis that the statistics “have received considerable publicity.” It then proceeds to fill in what it calls “the total picture which it claims “is less well known.”

The first data it provides is a general statement from the report prepared on behalf of the federal government under the supervision of H. Gray, presently a cabinet minister in the Trudeau government. In 1968 (five years ago) “26.8% of Canada’s total industrial assets were 50% or more non-resident owned.”

As valuab1e as it is, this figure, in our opinion, is not really adequate to help us arrive at an accurate understanding of the weight and significance of foreign ownership (largely US) in the Canadian economy. In fact it could actually prove to be misleading. We have previously noted that the 50% non-resident ownership breakpoint is now no longer being used by Ottawa itself. It will be defining that 25% (not 50%) foreign ownership of the voting shares publicly traded is assumed to mean foreign control.

Furthermore, since “26.8% of Canada’s total industrial assets were 50% or more non-resident owned” can we say that the rest, some 73.2% were Canadian owned in 1968? By no means! These Gray Report figures come from the 1968 report on the Corporation and Labor Unions Returns Act (CALURA) which exempt many companies. The exemptions encompass firms with as assets less than $250,000 or gross revenues of less than $500,000. It also exempts all corporations regulated by other statutes such as the Bank Act, Loan Companies Act, Small Loans Act, Radio Act, Canadian and British Insurance Companies Act, the Railway Act, and Crown Corporations. Companies governed by the latter two categories, we will find, are given particular significance by the authors of Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism. The assets of these non-reporting companies, which for the purposes of the report are considered by Gray’s statisticians to be largely Canadian, are estimated at some 35% of total corporate assets, or 67 billion dollars.

To compensate for the inadequacy of the 26.8% figure there is some other data relevant to it in the Gray Report. The value of assets of all corporations with at least 50% foreign ownership was almost $51 million in 1968. This 1968 figure was 13.3% higher than in the year earlier and was up an astonishing 71% in the past five years, (1963-1968).

Further, of all non-financial corporations in Canada, an estimated 39.4% of Canada’s industrial assets in 1968 were in companies with 50% or more foreign ownership. This had increased from 33% in 1967, and was up from 36% at the end of 1965.

The Select Committee, set up in response to public pressure by the Ontario Government, to investigate how other countries cope with foreign investment, gave a press interview while in Bonn, Germany (Toronto) Star, October 7, 1972). European financiers are reported as having told the committee that the Ontario government’s proposal to screen investments is very modest and will have little meaning. Dr. A.E. Sulzer, chairman of the Zurich Handelsbank, told the committee that Canada only changed mother countries—from Britain—and is still a colony—to the United States. The committee also released some data on foreign investment in European countries.

It appears that in Germany direct foreign investment is under 10%. In France it is 6%. We are not able to give a comparable figure for Canada—but even accepting the 26.8% figure—it is clear that the weight of direct foreign investment in Canada is three and four, and probably many times higher than that.

According to these European economists, foreign investment in the European economies has another marked difference from that in Canada. The US does not completely dominate any European industry. Thus US investment, whatever proportion it is of the above figures in other advanced capitalist countries, is not only different in Canada, from the point of view of its relative weight; it is also different from the point of view of its strategic character.

US capitalist investment in Canada dominates what are in fact the strategic sectors of the economy, the manufacturing assets, as the figures sketched in Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism reveal. Almost 60% (58.1%) of all manufacturing assets in the country are foreign-owned—“including 99.7% of Canada’s petroleum and coal products, 93.1% of rubber products, 87% of transport equipment, 81.3% of chemicals and chemical products, 72.2% of machinery, 64% of electrical products—“ (and we would add from the same Table #3 in the Gray Report, somehow overlooked by Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism), 55.2% primary metals, 51.6% in non-metallic mineral products, 46.7% in metal fabricating, 84.5% of tobacco, 39.2% in textile and clothing, 38.9% in paper and allied, 53.3% in miscellaneous manufacturing. Said another way, in 1965, some 57.9% of all assets in manufacturing were in companies with 50% or more foreign investment—by 1968 it was 62.8%.

It is these figures that reveal the strategic position US capitalism holds on the Canadian economy. These figures show that the US bourgeoisie controls what are accurately called the commanding heights of the Canadian economy. Data that we will present later in this document on the largest manufacturing resources and utility companies confirms this picture.

“The total picture” which is “less well known,” according to the authors of Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism is presumably contained in the data dealing with “other sectors of the economy (where) ownership is considerably smaller.” Their next four lines of figures deal with other industries (other than manufacturing). We will reproduce them as, since further along Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism gives them major significance—“12.6% of the assets of financial industries, 21.2% of retail trade, 15.7% of public utilities, 13.8% of construction, 8.4% of transportation, and )(6.4%?—illegible --ed.) of communications.”

These figures are taken from Table #4 of the Grey Report, although one item in that table to the effect that non-resident ownership accounts for 31.4% of all assets in Wholesale Trade was overlooked. Some of these industries receive special attention later on in the documents. They are referred to as “vital areas” (transport and utilities) and as “key” sectors of the economy.

Why is what Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism calls “the total picture,” the immediately above information, “less well known"? The reason, in our opinion, is quite simple. The most important facts are clearly that foreign ownership encompasses almost 60% of all manufacturing assets in Canada, and indeed nearly all the assets in certain industries, and the decisive majority in many others. The other facts are far from providing “the total picture". In reality they only play a diversionist and confusionist role by tending to obscure the facts of the domination by US capital of Canada’s manufacturing assets which are the strategic or commanding heights of the Canadian economy.

When first taking up the document Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism we could not understand how, after dutifully providing us with the data on US domination of Canadian manufacturing assets, its authors could persist in repeating that “the key sectors” and “vital areas” of the economy are in the hands of Canadian capital. We thought that it was merely an aberration in the document, and in fact, at one point, in a previous contribution, we even went so far as to mistakenly say that they concede that the strategic or key sectors of the Canadian economy are dominated by US capital. But on closer examination we conclude that without really bringing it sharply to our attention they give quite a different meaning or context to the words “key” and “vital” than has been traditional in our movement, and is now commonly understood in wide layers of the Canadian popu1ation.

On closer examination we note that the authors of Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism never use the words “key,” or “vital,” to describe those areas of the economy that US capitalism dominates—petroleum-coal, rubber products, transport equipment, chemical products, electrical products, machinery, etc., etc.—the manufacturing assets of the country. They reserve the use of these words to characterize other sectors of the economy. The “vital areas,” the “key areas,” according ‘to Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism are transport, utilities, and as we saw earlier—the banks.

In so doing it wou1d appear that the authors of Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism are only following the lead of the economists who drew up the Gray Report—and in a very mechanical way at that. The government economists us the phrase “key sectors” in that section of their report that deals with how foreign investment has been coped with in other countries, none of which, they seem obsessed in repeating, “has a situation remotely resembling the Canadian picture.” It is one of four arbitrary divisions they employ.

They note that what is called or designated a key sector by various governments varies widely from country to country and the criteria are “seldom made clear”—“in some cases it clearly reflects historical concern about what were in the past, industries of great strategic importance, either for military or economic reasons.” They use the word “vital” to describe an industry whose functioning in the economy is important to the economy’s functioning as a whole—a part of what one might call the nervous system of an economy.

In the first category in Canada, we would suppose there would be an inclination from former days to include the railways and canals, and today to include the uranium industry. In the latter category we would anticipate the inclusion of the waterworks and the hydro system (Ontario Hydro is the second, after the Tennessee Valley Authority, largest public utility in North America) and as Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism states, the “telephone monopolies,” which in BC are dominated by a US-owned corporation, and in the East by the US-controlled Bell (Canada). Many of these sectors are under public ownership Canada as they are in other advanced sectors of the capitalist world. The Ontario Hydro system was organized some fifty years ago under a Tory government.

Now we can understand the authors of Canada and the Crisis Of World Imperia1ism when they refer to “vital areas” and “key sectors of the economy” where they claim the Canadian bourgeoisie has consciously striven to “retain control” and where they note “foreign ownership is virtually non-existent.”

While state or public ownership of industries in both transportation and utilities “blocks” foreign capta1 takeovers or control (and it is possible that in some cases it could be proven that public ownership was designed to do that) as the authors of the Gray Report themselves note, public ownership is directed not a much against foreign control as away from private ownership, foreign or Canadian. By so using public funds the state serves the capitalist class as a whole, removing these sectors from inter-capitalist rivalries. By and large it can be said that Capitalism, particularly foreign capital in the advanced sectors of the world, does not seek to invest in these areas but prefers that these facilities already be developed, be provided, so that they can move in easily to take advantage of much more profitable areas that they seek to open up. Instead of being blocks against foreign capitalist domination of the economy, Canadian capital, most often public, provided them almost as a matter of course to attract capital investment to exploit natural resources and the work force.

That transport and utilities are highly developed in Canada is an attribute of its essential character—that it possesses an advanced capitalist economy, that it has a skilled work force, and even more, in the age of automation, an efficiently organizable work force—that it is an integral part of the world capitalist economy. It is these attributes that give Canada the characteristics, not of a colony or a semi-colony, but its capitalist-imperialist character.

In our opinion this “key” and “vital” sector approach of the Gray Report, regrettably pursued by the authors of Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism is worse than useless to Marxists. In an advanced capitalist economy such as Canada, it is the manufacturing sectors that are the most important. It is they that determine the extent of expansion or contraction of the economy, that determine the class relations of society, the specific weight of classes and their dynamic, that exert the greatest influence on the state and that determine the weight of the nation-state on the international economic-political arena.

Fortunately we do not have to speculate or search far afield for data as to the strategic importance of manufacturing in the Canadian economy and the dynamic character that the decisive weight of the US-owned sector (almost 60%) gives to the Canadian economy.

According to the Gray Report the sales and assets of all foreign-owned firms averaged respectively $6.34 million and $7.8 million. The comparable values for Canadian-owned firms were $162 million and $2.45 million. The same information for all manufacturing firms show foreign-owned manufacturing firms had average (sales of $12.11 million and assets of $11.44 million, whereas Canadian-owned firms had (insert on page bottom -ed.) sales of $3.03 million and assets of $2.58 million. This data excluded companies with sales of less than $500,000 and assets of less than $250,000.

In addition to being larger, foreign-owned manufacturing firms are the more capital intensive. A 1967 study revealed that foreign-owned firms accounted for 30% of Canadian manufacturing employment but 60% of the book value of the corporate assets. According to a 1970 study—three times more foreign-owned firms were among the eight largest firms in their industries than those among the smaller firms in their industries.

US corporate heads with large scale investments in Canada do not appear to have any of the doubts about the security of their position in the economy or their power over the Canadian state that the authors of Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism should logically expect them to have—from the battery of safeguards they claim the Canadian capitalist class have erected against them.

The US corporate giants fully grasp the strategic position they hold over the Canadian economy. Some of them would appear to consider Canada to be not on1y a prime area for investment but perhaps even better than inside the borders of the United States itse1f. Again, according to the Gray Report, Canadian manufacturing industries are more highly concentrated than corresponding industries in the US. Some 34% of Canadian manufacturing shipments in 1964 came from industries in which 8 or fewer firms accounted for 80% of the total value of industry shipments. On1y 13.7% of United States manufacturing shipments came from industries concentrated to that extent.

Not long ago, Waffle circles (the left-nationalist current in the Canadian labor party, the NDP -ed.) were abuzz with talk that US investors were preparing to pull back from Canada, into “fortress America,” and in the process, preparing to phase out, among others, their Canadian auto interests and scrap the pact through which they have developed a North American integrated auto industry. Recently, when opening up a winter testing plant in the Ontario north, the president of General Motors (Canada), John D. Baker, gave some insight into the importance of G.M.’s Canadian investment. The Oshawa GM plant holds second place among all seven GM North American plants in quality of production of the Chevrolet, first among the five plants that produce the Chevelle, and first among the seven that produce its light duty trucks. The Vega production line at the St. Therese, Quebec plant, is ahead of its only competitor—the super Lordstown, Ohio plant.

We have not come across this peculiarly tacked-on figure concerning Canadian ownership of steel anywhere, and find it difficult to understand, all the more in view of the data on manufacturing that Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism overlooked but which we have supplied. According to the Gray Report, foreign owners control 55.2% of all assets in primary metals and 46.7% in metal fabricating. But just in case we may have missed something we have tried to check cut the major four basic steel corporations. After looting the pub1ic treasury for subsidies for many years, the British Hawker-Siddley interests finally sold out Dominion Steel and Coal to the Nova Scotia government. Algoma would appear to be largely owned by the West German Mannesman Steel interests, in part by the British investment trust Locana Corporation, British Hawker-Siddley interests, and some Canadian interests—McIntyre Porcupine group. As for Stelco and Dofasco, they appear to be among those companies that are highly favored by mutual funds, investment trusts, insurance corporations, are highly influenced by the banks, and in the light of the scope of Canada-US integration, while perhaps they are Canadian-owned are in the orbit of US control.

We would also add that through their control of the vast northern Quebec iron ore deposits, Iron Ore of Canada (owned by the US Hanna interests) exported 165 million gross tons in the years 1954-68, most of which went to the US. Of 1970 ore production in Quebec—65% came from iron Ore of Canada, 24.3% from Quebec Cartier (100% controlled by US Steel) and 15% from Wabush Mines (half US, half Canadian-owned). In order to protect their US Mesabi Range deposits, the US corporate owners of Quebec iron ore have fixed the price of ore, whatever its origin, as if it came from Lake Erie, plus transportation from there. Canadian-owned mills, which receive almost all their ore from the US, pay that price—from the CSN (/CNTU, Manifesto of the most militant of the Quebec labor federations, le Conseil des Syndicats Nationaux -ed.)—It’s Up To Us.)

From there we move along to the two lines “in addition, the Canadian bourgeoisie has ensured it is in firm control of the mass media,” to a paragraph which relates at some considerable length, from a book entitled Foreign Ownership, five areas where the federal government has taken measures to protect “Canadian autonomy."

A most peculiar aspect of all these detailed efforts by the Canadian bourgeoisie, armed with their state, to protect Canadian autonomy, is that the commanding heights of the Canadian economy are nonetheless now firmly in the control of US corporate power. They are neither in the hands of the state (for all the state intervention in the economy, Canada could by no means be said to be approaching anything like a state-capitalist economy with vast sectors ready to be plucked by an elected NDP government) nor are they in the hands of private Canadian capital. We are forced to conclude either (1) that the Canadian state under the authority of the leading capitalist interests did not and does not now go far enough in the direction of protecting Canadian autonomy, or (2) if it once did move out with the public purse or continues to do so, it is for quite other reasons than to protect Canadian autonomy.

There is no question that state funds and government lands were handed over generously to the building of the railways, to pull the country together, to open up the West, and to funnel out of it the great grain crops from both north and south of the border to the world market. But the loot from the public treasury, and the land grants with their mineral rights were handed over, not to a state-controlled operation but to private capitalist interests. Subsequently more state funds were turned over to the railway owners when the government bailed them out of their bankruptcy, honoring their bondholders, and took over what subsequently became the state-owned, and still, a half a century later, the notoriously debt-ridden, CNR.

It is not possible to leave this section of the document Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism without saying something about the statement that “the Canadian bourgeoisie has ensured it is in firm control of the mass media.” Surely this statement is meant ironically, or at the very least, surely it is said tongue-in-cheek.

It is true that there was a brief recently submitted to the Ontario government select committee on economic and cultural nationalism, expressing fears about legislation that would “affect the ability of the advertising industry to operate in the national interest” and that warned about vociferous Canadian nationalism that operates unfairly and “smacks of economic and political terrorism.” The brief was submitted to this Canadian government committee by 10 of the largest US-based and owned advertising agencies that operate in Ontario.

Their brief said nothing to deny the claims that the US advertising interests dominate Canadian advertising. They assured the committee that 95.8% of the employees of these international subsidiaries are either Canadians or landed immigrants from other countries than the US, and that 65% of the members of their Canadian board of directors are Canadian citizens.

The Senate Committee on mass media, reported in early 1970 that one quarter of the institute of Canadian advertisers’ member-agencies were US-owned, and that together they accounted for about 37% of the total $460 million in annual agency billing. The present rate of growth of such US agency billing is 1.1% per year. “In other words, in 10 short years,” yet another Canadian industry—this time advertising—will be more than 50% in the hands of American interests.”

The committee-head, Senator Keith Davey, recently told the Calgary Chamber of Commerce that two US magazines, Time and Readers Digest, take in 2/3rds of all available national magazine advertising in Canada. He warned that the Canadian magazine industry will die unless the government ceases its policy (the president of the United States personally intervened on behalf of Luce interests when the Commons was debating this policy) of giving these two magazines exemption from legislation preventing advertising in US publications as tax deductible business expense. This adaptation to Canadian private capitalism’s advertising in the US mass media is hardly an act to defend Canadian autonomy.

In order to survive, “Canada’s national magazine” Maclean’s has had to go so far as to actually reduce its format down to the size of Time, so it can use Time’s layouts and plates from the ads that it carries, into the Canadian market through its Canadian edition.

The state-owned CBC was established early during the rise of radio to provide a national broadcasting service filling in areas where private capital did not find it to be profitable, and in passing provide a “service that is predominantly Canadian in content and character.” Under Quebec pressure it also provides a French language service to cut across the torrent of English, largely beaming in from the US—which is a chief threat to Quebec language and culture.

But once the market for TV was firmly established with government subsidies, the CBC monopoly was broken and the field opened to private capital. Today, while CBC English TV network reaches 95% of the English-speaking population—the independent CTV network is moving to take up its potential 77% of this audience which is the most profitable.

CBC TV, despite government subsidies, Canadian content rules, and its contracting in on the most popular US programs, has been unable to compete in the major population areas of the country with US TV and its 100% US programming, From a recent study it has been estimated that Metro Toronto audiences spend just under 22 1/2 % of their TV viewing-time looking at Canadian programs. And of that 22 1/2%, all but a tiny 9% (Canadian drama, comedy, variety and public affairs) was spent watching hockey games.

While it is true that the Canadian state has set up regulatory boards and a whole list of structures “controlling” the mass media, there is no area where the Canadian bourgeoisie, if it were to define its interests as in conflict with those of the US bourgeoisie’s, it could be said to be in less control. The US-domination of the mass media, both indirect and direct has been the source of a whole series of hearings, commissions, etc., and is amply documented.

In general, we can say that the Canadian bourgeoisie has made state resources available for state-owned corporations when private capitalist interests were not able to, or were unwilling to amass the necessary capital (they were too weak or were looking to more profitable areas for investment) and used the state purse to provide services that are in the interests of the capitalist as a class besides being in the interest of society as a whole. Or when private ownership or competition between rival capitalist interests would tend to cut across the interests of the capitalist class as a whole, and the development of the economy in their overall interests. In the latter case we have public ownership directed not against foreign ownership in principle—but away from private ownership—foreign or otherwise.

If there are some notable aspects about Canadian state intervention in the economy not covered by the above general rules, we should note that a great many of the circumstances made so much of by Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism are common to all advanced capitalist countries. “In the US,” the Gray Report notes, “foreign participation is prohibited or restricted in shipping, broadcasting, communication satellites, hydro electric power, or activities associated with atomic energy, and banks.”

The protective tariffs referred to in Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism have been employed by all developing capitalist nation-states and continue to be employed. In Canada’s case, while they were designed to protect growing Canadian industries, they also served to compel the more developed US industries (whose eyes were much more concentrated on a readily accessible source of raw materials for a whole period rather than a Canadian market) to erect branch plants which were further enticed by the preferential tariff system that Britain granted Canadian resident industry, in return for other concessions.

It was these branch plants, some of which retained a truncated character—as a part, with no function separate from a more developed part located in the US which it was designed to feed into—and others which developed a finished product, directed primarily to sale on the world market, and in particularly into the British Commonwealth market due to special tariff privileges granted to Canadian goods—that assured that the Canadian market developed along US lines. In a period of expansion this made the US takeover of private Canadian corporations an attractive proposition. The essential facts of US capitalist domination of the Canadian economy are undeniable. Nor are the dynamics of the processes at work hard to grasp.

The book value of all foreign investment in Canada in 1968 stood at $40.2 billion. At the end of 1969 it had risen to $46 billion—the overwhelming bulk of it, some $41 billion, is long term investment, of which 80% is US-owned. Whereas in our 1968 document we said that US investment in Canada was greater than in all Latin America. It now exceeds the total direct investment in Europe and also the total US investment in Central and South America.

According to Eric Kierans (late winter 1972) “there is already a sufficiently large foreign involvement in Canada to maintain itself at a rate compounded annually that will ensure its continued domination.” All during the 1950s US direct investment inflows exceeded remitted profits by 1.2 billion dollars. However in the period 1960-67 remitted profits ($5.9 billion) exceeded new capital inf1ows ($4.1 billion) by $1.8 billion. In the recent period the US owners have been able to expand their subsidiaries in Canada without investing new capital but from the profitability of the present investment. In l967—64% of expansion, or $374 million, was provided US subsidiaries from Canadian sources.

And the flow of new capital continues. The dynamics of the process in this respect are only hinted at in the figures showing the rapid increase in the takeovers, the buying outright of existing Canadian private capitalist institutions by US corporations, and the buying-into existing operations, so that while the actual ownership of many corporations may be in doubt, their control through the complex of interlocking relationships is soon apparent to be US. There are the new opportunities opening up—primarily in the exploitation of the vast and incredibly valuable natural resources, such as the Mackenzie Valley pipeline and the James Bay projects, that require such vast sums, an estimated 12 billion dollars or more, that only the US corporate power can amass, before Canadian capital even gets a look-in.

This process is so dynamic and all-engulfing that it is impossible to conceive that we are witnessing today “a powerful homogeneous highly conscious (Canadian) bourgeois ruling class firmly in control of its own state power, ruling in its own name,” as Canada and the Crisis of World Imperia1ism (claims).

In fact, and not without cause, some even question that there are any survivors of the species bourgeois Canadiensis, that such a species can be said to even exist today. Such Canadian bourgeois nationalists as Jack McClelland of McClelland and Stewart Publishers (who wants to sell out but can only find US buyers) and Mel Hurtig, joined by the respected and all-the-more-isolated- for-that ideological refugees from the Liberal Party, Eric Keirans, ex-head of the Montreal Stock Exchange, ex-Liberal government cabinet minister and Walter Gordon, ex-corporation lawyer, ex-board member of Brascan, ex-Liberal cabinet minister, have been searching for some elements among their class in whose breasts there may still flicker a flame of national pride and entrepreneurial initiative of fabled yesteryear—in vain.

The behaviour of the Canadian bourgeoisie has been a matter of endless worry and persistent enquiry, of irritating perplexity for the voluble Abraham Rotstein, economics professor and editor of Canadian Forum. He has set himself the task of saving the Canadian bourgeoisie for themselves. How to account for their indifference to the urgent national tasks, their lack of patriotism, their alienation—is there something in Canadian business tradition that causes them to want only orderly and controlled expansion? Why, he persists in asking, are they hooked on US investment? The Canadian bourgeoisie must appear to Rotstein to be, along with K.C. Irving and E.P. Taylor, on pension—in the bars and on the beaches of the salubrious Bahamas; lotus eaters, when the times call for a Ulysses.

We can even imagine these questions and images arising in the minds of the readers of Canada and the Crisis of World Imperialism because of its one-sided and completely erroneous portrayal of the Canadian bourgeoisie as a major imperialist force, powerful, cohesive and highly monopolistic, in full control of the Canadian economy, capable of redirecting Canadian imports and exports in totally new directions on the one hand; and on the other, its one-sided and quite erroneous portrayal of the American bourgeoisie—beset on all sides, confronted with nothing but immediate and endless dilemma. All the talk about the Canadian banks not just as powers on the Canadian scene but on the world arena, can only lead to such confusion. All the more when the simple truth is that the assets of the Canadian big five account for less than 9% of the total assets of the 50 largest commercial institutions outside the United States of America—not to mention the fact that the assets of the Bank of America alone are almost three times the assets of Canada’s biggest, the Royal.

The Canadian bourgeoisie certainly exist. They have lost control of the commanding heights of the economy, and can no longer be said to rule the Canadian economy. But they are still in there. It can even be said that while in relative decline vis-à-vis the US ruling class, the Canadian capitalist class have risen in terms of real, absolute wealth at their disposal. They have gone up automatically on the scale of accumulated wealth, as the whole economy has expanded. Like the lamprey feeding and fattening on its body they have moved with the shark.

The explanation of their relative eclipse lies not in their psychology, but in the conditions that determine that psychology. It is not initiative, not ingenuity that they lack—so much as capital. And not capital alone—but in many cases the wide-ranging connections that the vast, largely US multinational corporations have with every aspect of some of the projects to be exploited. Many of the multinational corporations that Canadian entrepreneurship is up against, not only have all the necessary engineering skills, they have all the high-level relations with governments, the connections with the concrete manufactures, the steel pipe manufacturers, the corporations that utilize the finished and semi-finished products along the way—including the gas and the hydro marketing agencies.

There is no question that to some considerable degree the Canadian bourgeoisie have been overwhelmed by the colossal inrush of US interests and the assiduous courtship by its representatives. In this sense they may have had their old confidence, their sense of power and creative purpose somewhat undermined by the high-powered teams of business and technological specialists that the US bourgeoisie have brought in with them from New York, Cleveland and Los Angeles. For corporate power of such scope, having once made a decision, money is no object, nothing stands in the way—except sporadically, labor.

One can imagine the palpitations of Quebec’s Premier Bourassa, harassed by widespread unemployment, when he was approached by representatives of the US conglomerate International Telephone and Telegraph-Rayonier—the 11th largest company in the world with access to all markets across the globe through its operations in 67 countries employing 392,000 people. They proposed to build the world’s largest cellulose acetate factory in Port Cartier, with an initial capacity of 263,000 tons a year. It is no wonder that the decks were cleared to grant them a private domain of 26,000 square miles within a state forest of 51,000 square miles—three times the size of all Ireland, for their purposes. The cellulose acetate will go to ITT-Rayonier’s West European market which requires two million tons a year. Of course, Canadian ownership, actually public ownership, will rise—to the tune of $40 million which Ottawa and Quebec agreed to chip in towards the construction of the plant and related installations—probably roads, water, hydro.

In this sweeping process of integration of the Canadian economy with that of the US, a process which included the buying up of Canadian corporations, their continuation under new ownership, their disappearance through assimilation into an already US-owned operation, or complete phasing out of some of their components—the buying into Canadian operations, retaining Canadian participation and possibly linking it up with expanded US-owned operations—and the setting up of new US-owned operations with Canadian capital providing a Canadian presence—it is no wonder that the definition of ownership and control has become confused.

It is no accident that the authors of the Gray Report assigned to make findings and recommendations on the flood of US investment in Canada ask: are Alcan and Seagrams really Canadian controlled?—and point out that in the case of many corporations identified as Canadian-owned, “their Canadian identity becomes nominal, e,g., Inco and Massey-Ferguson.” Business secrecy is a problem but it is primarily that the degree of integration is so high and often so complex through interlocking relationships, that it is difficult to establish worthwhile, meaningful criteria.

The August 5, 1972 Financial Post published the list of the 100 largest manufacturing, resource and utility companies in Canada, compiled on the basis of the latest available results for the fiscal year ended nearest Dec. 31, l972. The list is the most realistic yet according to FP (although 13 made it for the first time) because as federally incorporated companies under an amendment to the Corporation Act, they now have to file financial statements. That left out some large companies “because they do not publish financial statements and reliable estimates are not available. These are mostly subsidiaries of US and other foreign companies—such as Canadian International Paper Company and Kel1ogg Co. of Canada, which undoubtedly would rank in the 100 largest.” Elsewhere Financial Post notes that Canadian International Paper (the Quebec subsidiary of the US International Paper) has a provincial and not a federal charter. Eaton’s doesn’t appear though it would probably have rated second or third by sales volume in the line up of the top 10 merchandisers, because it is a provincially incorporated private company. The US-owned Simpson Sears operation is now in close contest with Eaton’s. None of the mutual fund organizations such as the US-owned Investors Group (see our contribution on the banks) which controls assets of over one billion dollars appeared on the list of the big 25 financial institutions because of the nature of their assets. By the same token, presumably Financial Post does not list Argus Corporation. Ten other giants, big enough to rank in the main list, do not appear on it as they are consolidated with their parent companies among them—Northern Electric with Bell (Canada) and BC Telephone, consolidated with Anglo Canadian Telephone—almost 84% owned by the New York General Telephone and Electronics Corporation.

Even so, the astonishing total of 62 of the 100 largest manufacturing, resource and utility companies in Canada, according to Financial Post, are foreign-owned or controlled—20 wholly owned subsidiaries of foreign-owned corporations, 28% more than 50% foreign-owned, and another 14 in which there is substantial, sometimes controlling foreign interest.

Financial Post placed both International Nickel and Alcan among the 62 foreign-owned corporations. Among the 38 Canadian-owned according to Financial Post’s statisticians, we find Massey-Fergusson and Distillers Corp.-Seagrams, along with Be1l (Canada) which we showed in a previous contribution is clearly controlled by American Telephone and Telegraph. To further add to the confusion we recall it is the authoritative government-sponsored Gray Report that links Massey-Fergusson (Canadian owned according to Financial Post) with the incontestably US-owned International Nickel as being among companies whose Canadian identity is “nominal.” The Gray Report also linked Seagrams (according to Financial Post Canadian-owned) with the incontestably US-owned Alcan by querying, are they “really Canadian controlled?”

Financial Post noted a change that took place over the last year. Two corporations just disappeared—International Utilities Corporation which had been right up in the top ten on the list, along with Chrysler (Canada) and Gulf Oil; and Hunter Douglas which had been with the top 70, right in with Falconbridge Nickel and BC Forest Products. When the Income Tax Act was revised on a basis that was unsatisfactory to them “they decided to shift their domicile from Canada.”

The significance of this action came up incidentally in the proceedings of the Senate Committee on Banking Trade and Commerce, when Senator Connolly asked whether Hunter Douglas and the Patino Company (which apparently had also left Canada) are US-owned. He was told, “No, they are Canadian.” This was affirmed by the chair—“These are Canadian corporate companies regardless what their ownership might be”

At the Senate Committee proceedings of November 3, 1971 there was a discussion on Iron Ore of Canada and its status. Iron Ore is the major ore producer from Quebec’s fabulous iron deposits. According to 1970 Quebec production figures 65% came from Iron Ore of Canada, 24.3% from Quebec Cartier Mining (100% owned by US Steel) and 15% from Wabush Mines (half Canadian and half US-owned). Hanna Mining, the largest buyer of iron ore in the US, owns 22% of National Steel and through a subsidiary, 9% of Chrysler. In 1942 Hanna Mining established an operating relationship with Hollinger Mines and Noranda Mines. With Hollinger and Noranda providing the necessary “Canadian content” Hanna got vast concessions in the Northern Quebec iron deposits. Of course the E.P. Taylor interests (HolIinger) and the J.Y. Murdoch interests (Noranda) got a cut, but the real rake-off goes to Hanna. It invested slightly more than 40 million in Iron Ore of Canada over 1954-68 and received $80 million in dividends which of course went to the owners in the US.

Two subsidiaries were set up to carry it off—North Shore Exploration (60% Hollinger and 40% Hanna-owned) and Labrador Mining and Exploration (59% Hollinger and 22% Hanna-owned.) Out of these manipulations Iron Ore of Canada arose with ownership divided as follows—5.4% Labrador Mining, 11.6% Hollinger Mines and 26.8% Hanna (US), 16.8% National Steel (US) and 39.1% other US steel mills—all but 17% US-owned .

An excerpt from the Senate Committee hearing follows:

Mr. Fairley: Iron Ore Company would not go into this unless the Iron Ore Company were an American company so that they could get a tax advantage to them on dividends. We being the only Canadian owners of this company—that is Hollinger Mines and Labrador Mining—we could not have it as an American company because we got caught up here in the same way working the same way. So what the government did with Mr. Finlay, Mr. Howe, and a whole lot of other people working on it—