Law of the Accumulation and Breakdown, Henryk Grossman 1929

An abstract deductively elaborated theory never coincides directly with appearances. In this sense the theory of accumulation and breakdown expounded above does not directly correspond with the appearances of bourgeois society in its day to day life. The conditions of capitalism conceived in its pure form (which we have analysed so far) and those of the system in its empirical manifestations (which we have to analyse now) are by no means identical. This is because a theoretical deduction involves working with simplifications; many real factors pertaining to the world of appearances are consciously excluded from the analysis.

So far we have assumed:

i) that the capitalist system exists in isolation - that there is no foreign trade;

ii) that there are only two classes — capitalists and workers;

iii) that there are no landowners, hence no groundrent;

iv) that commodities exchange without the mediation of merchants;

v) that the rate of surplus value is constant and corresponds to the magnitude of the wage — that is a rate of surplus value of 100 per cent;

vi) that there are only two spheres of production, producing means of production and means of consumption;

vii) that the rate of growth of population is a constant magnitude; viii) that the value of labour power is constant;

viii) that in all branches of production capital turns over once a year.

Any theory has to work with such provisional assumptions which are a potential source of mistakes. But these assumptions have allowed us to determine the direction in which the accumulation of capital works, even if the results of this analysis have a provisional character.

Marx was perfectly conscious of the abstract, provisional nature of his law of accumulation and breakdown. Having presented ‘the absolute general law of capitalist accumulation’, he says that ‘Like all other laws it is modified in its working by many circumstances, the analysis of which does not concern us here’ (1954, p. 603). Elsewhere, in describing the process of accumulation, he writes: ‘This process would soon bring about the collapse of the capitalist production were it not for counteracting tendencies’ (1959, p. 246). Marx gave an analysis of these counteracting tendencies in various places in Capital Volume Three as well as in Theories of Surplus Value.

Once we have shown the tendency of accumulation in its pure form we have to examine the concrete circumstances under which the accumulation of capital proceeds, in order to see how far the tendency of the pure law is modified in its realisation. We are asking whether, and if so in what direction, the tendencies of development of the pure system are changed once this system reincorporates, by degrees, foreign trade, landowners who live off groundrent, merchants and the middle classes — and once the rate of surplus value or the level of wages are allowed to vary. These considerations mean that the abstract analysis comes closer to the world of real appearances. It enables us to verify the law of breakdown: to see to what extent the results of the abstract theoretical analysis are confirmed by concrete reality.

Considering the gigantic increases in productivity and the enormous accumulation of capital of the last several decades the question arises —why has capitalism not already broken down? This is the problem that interests Marx:

the same influences which produce a tendency in the general rate of profit to fall, also call forth counter-effects, which hamper, retard, and partly paralyse this fall. The latter do not do away with the law, but impair its effect. Otherwise, it would not be the fall of the general rate of profit, but rather its relative slowness, that would be incomprehensible. Thus, the law acts only as a tendency. And it is only under certain circumstances and only after long periods that its effects become strikingly pronounced. (1959, p. 239)

Once these counteracting influences begin to operate, the valorisation of capital is reestablished and the accumulation of capital can resume on an expanded basis. In this case the breakdown tendency is interrupted and manifests itself in the form of a temporary crisis. Crisis is thus a tendency towards breakdown which has been interrupted and restrained from realising itself completely.

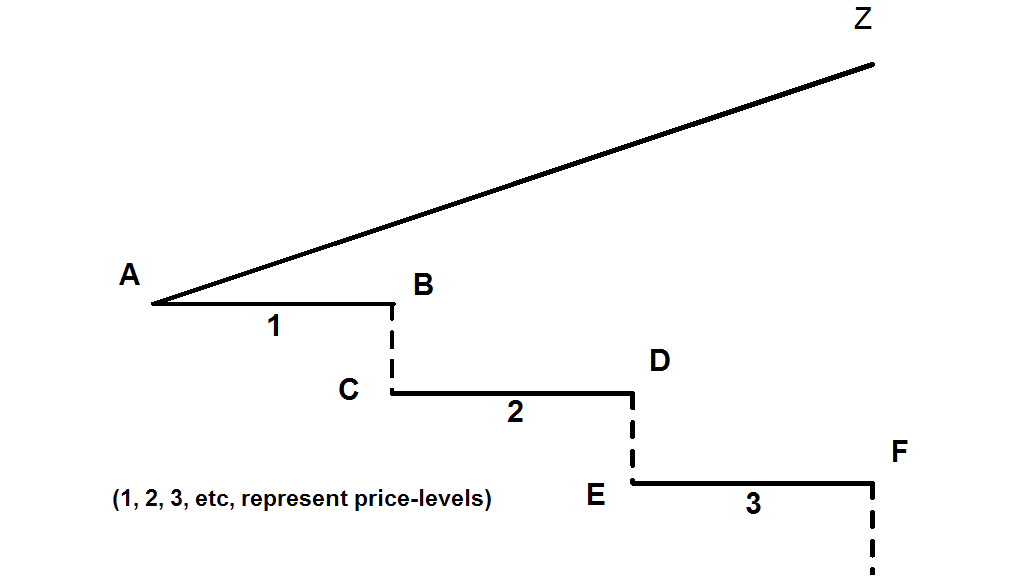

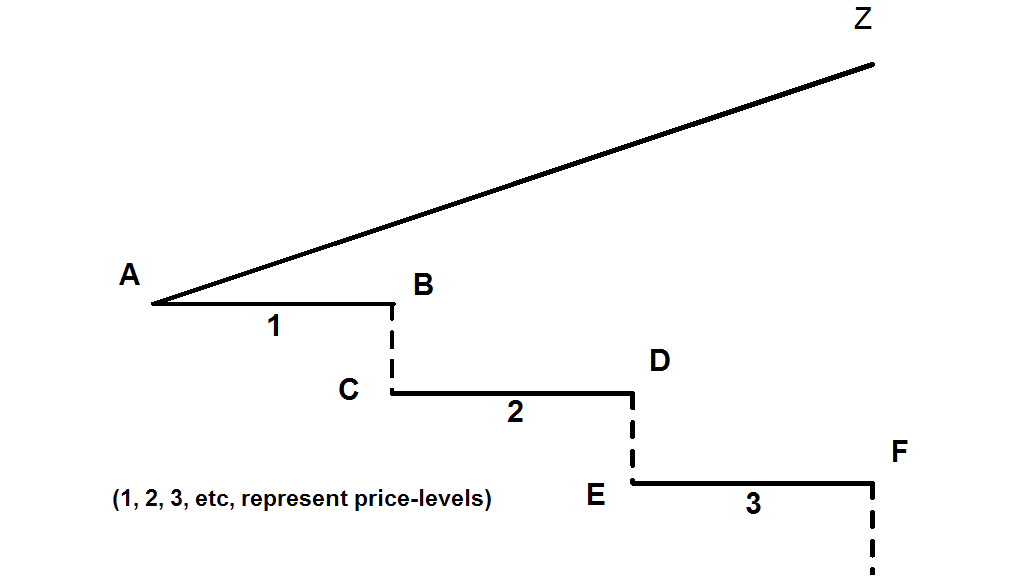

Return for a moment to the illustration of the cyclical process of accumulation in Figure 2 above.

Due to the very nature of the accumulation process there is a basic difference between the two phases of the cycle with respect to their duration and their character. We have seen that only the phase of accumulation is defined by a specific regularity; that only the length of the expansion phase(O-Z1, O-Z2...) and the timing of the downturn into a crisis are open to exact calculation. No such calculation is possible with respect to the duration of the crisis (Z1-O1, Z2-O2 ... ). At Zl, Z2, and so on valorisation collapses. The ensuing overproduction of commodities is a consequence of imperfect valorisation due to overaccumulation. The crisis is not caused by disproportionality between expansion of production and lack of purchasing power — that is, by a shortage of consumers. The crisis intervenes because no use is made of the purchasing power that exists. This is because it does not pay to expand production any further since the scale of production makes no difference to the amount of surplus value now obtainable. So on the one hand purchasing power remains idle. On the other, the elements of production lie unsold.

At first only further expansion of production becomes unprofitable; reproduction on the existing scale is not affected. But with each cycle of production this changes. The portion of the surplus value earmarked for accumulation each year goes unsold. As inventories build up the capitalist is forced to sell at any price to obtain the resources to keep the enterprise going on its existing scale. He is compelled to reduce prices and cut back on his scale of production. The scale of operations is reduced or they shut down completely. Many firms declare bankruptcy and are devalued. Huge amounts of capital are written off as losses. Unemployment grows.

This sickness leads in one of two directions. Either there is nothing to stop the breakdown tendency from working itself out and the economy simply ceases to function; or specific measures are undertaken to counteract the sickness so that the sickness is stopped and turns into a healing process. The question arises: how is a crisis surmounted? How is a new period of upswing initiated? The mere statement that crises are a form of sickness is quite useless if we have no conception of what this sickness is caused by. The specific means by which a crisis is surmounted are obviously closely related to the diagnosis of the sickness. The remedies prescribed would vary according to whether the underlying cause of crises is seen as the underconsumption of the masses, as disproportions between branches of production or as a shortage of capital.

There are, of course, cases where the boom has been precipitated by a massive flow of funds from abroad — for instance, the huge imports of American capital into Germany over 1926—7. But in numerous instances —and this is the general rule — crises have been surmounted without any flow of foreign funds. And just as crises have been surmounted while many of its so-called causes (for instance, underconsumption of the masses) are still present, so we find that all the factors generally cited to explain the boom turn out to be quite useless in explaining how the depression itself is overcome. The remedies proposed are not logically connected with the diagnosis of industrial sickness.

In contrast to these various theories, our theory shows that the means actually enforced to surmount a crisis correspond perfectly to the actual causes of industrial sickness in our analysis. In this sense the theory provides a consistent explanation of the two phases of the industrial cycle, both of the turn from expansion to crisis and of the process through which the crisis is later surmounted. From the argument that crises are caused by an imperfect valorisation of capital it follows that they can only be overcome if the valorisation of capital is restored. But this cannot come about by itself, merely in the course of time. It presupposes a series of organisational measures. Crises are only surmounted through such a structural reorganisation of the economy.

The capitalist mechanism is not something left to itself. It contains within itself living social forces: on one side the working class, on the other the class of industrialists. The latter is directly interested in preserving the existing economic order and tries, in every conceivable way, to find means of ‘boosting’ the economy, of bringing it back into motion through restoring profitability.

The circumstances through which the crises can be overcome vary enormously. Ultimately however, they are all reducible to the fact that they either reduce the value of the constant capital or increase the rate of surplus value. In both cases the valorisation of capital is enhanced — the rate of profit rises. Such circumstances lie both within production and in the sphere of circulation, and pertain both to the inner mechanism of capital as well as to its external relations to the world market.

The capitalist’s continual efforts to restore profitability might take the form of reorganising the mechanism of capital internally (for instance, by cutting costs of production, or effecting economies in the use of energy, raw materials and labour power) or of recasting trade relations on the world market (international cartels, cheaper sources of raw material supply and so on). This involves groping attempts at a complete rationalisation of all spheres of economic life. Many of these measures fall while the programme of reorganisation is often completely beyond the reach of the smaller enterprises, which are thus wiped out. In the end capital finds suitable means of raising profitability and a reorganisation is gradually enforced. By its very nature the duration of this reorganisation and economic restructuring process is something purely contingent and therefore impossible to calculate.

In the pages that follow I shall not go into a detailed description of all the several countertendencies that hinder the complete working out of the breakdown. I shall confine myself to presenting only the most important of them and to showing how the operation of these countertendencies transforms the breakdown into a temporary crisis so that the movement of the accumulation process is not something continuous but takes the form of periodic cycles. We shall also see how, as these countertendencies are gradually emasculated, the antagonisms of world capitalism become progressively sharper and the tendency towards breakdown increasingly approaches its final form of an absolute collapse.

In Chapter 2 I outlined the methodological considerations which prompted Marx to analyse the problem of accumulation and crisis on the assumption of constant prices. This assumption made it possible to prove that the cyclical movements of expansion and decline are independent of fluctuations in the level of commodity prices and wages. Here I want to show that the opposite assumption of the bourgeois economists, who take the price fluctuations as their starting point, simply confuses the issue.

We have already seen that in analysing the business cycle Lederer starts from rising prices as the decisive factor: ‘If we look at periods of boom, then we find that in such periods all prices rise’ (1925, p. 387). According to Lederer, expansions in the scale of production which characterise periods of boom are a result of rising prices. But how is the general increase in prices possible? Lederer argues that if the value of money is held constant a general increase in prices can only flow from changes on the commodity supply side. ‘However’, Lederer continues, ‘such changes in the volume of production are only consequent on changes in the level of prices’ (p. 388). So Lederer sees a vicious circle which can only be broken by new purchasing power being injected into the process of circulation by the expansion of credit. ‘Only credit creates the boom or makes it possible’ (p. 391) by raising the level of demand and therefore of prices. ‘Only through additional credit and thus newly created purchasing power is any significant expansion of the productive process possible’ (p. 387).

Lederer’s argument is unconvincing. Apart from its defective methodological starting point, it is both logically contradictory and contradicts the actual course of the boom. Firstly a general increase in prices is something meaningless apart from the case where the value of money falls. Yet such a general price increase is purely nominal - it has no impact on the mass of profit. Bearing this in mind the whole basis of Lederer’s deductions simply falls. Secondly the most important renovations and expansions in the productive apparatus occur in periods of depression when commodity prices are low. It is the demand generated by these programmes of expansion that raises the level of prices, assuming that this demand exceeds the supply.

In principle rising prices are by no means necessary in surmounting crises. They are only a consequence, not a cause, of booms. Extensions in the scale of production can, and do, occur without rising prices and even if the level of prices is low. This is basic to any understanding of the problem. According to Lederer rising prices and the programmes of expansion supposedly linked to them are a result of credit expansion. In which case it follows that credit is released when prices are still low. So Lederer has to be able to tell us who will take the credit to extend the scale of production when prices are low? Lederer is simply running in circles.

The fact remains that programmes of expansion are undertaken in periods of depression when prices are low. Any deeper analysis has to start here if we are going to understand the process in its pure form. At a certain level of the accumulation of capital there is an overproduction of capital or a shortage of surplus value. Overproduction does not mean that there is not enough purchasing power to buy up commodities, but that it does not pay to buy commodities for programmes of expansion because it is not profitable to extend the scale of production: ‘In times of crisis ... the rate of profit, and with it the demand for industrial capital has to all extents and purposes disappeared’ (Marx 1959, p. 513). Due to lack of profitability, accumulation is interrupted and production is carried out on the existing scale. Prices are bound to fall. The fall in prices is only a consequence of stagnation not its cause.

Because commodities are unsaleable when the crisis starts, competition sets in. Each individual capital tries to secure for itself, at the cost of other capitals, that which is unattainable by the totality of capitals. From a scientific point of view, this proves that competition is necessary under capitalism. We started by assuming the most favourable condition for capital, a state of equilibrium in which supply and demand coincide. Yet at a certain level of the accumulation of capital competition must necessarily arise. Earlier we looked at the capitalist class as a single entity. But in examining the crisis we must take account of the mutual competition of the individual capitalists.

Let us go back to the question posed earlier - how is the crisis surmounted? How does a renewed expansion of production come about? The answer is: through the reorganisation and rationalisation of production by which profitability is again restored even at the depressed level of prices prevailing. Figure 4 is a schematic illustration of the entire movement.

The crisis started at the prices prevailing at level 1. As a result the price level fell from B to C until they stabilised at their new and lower level 2 (line C—D). Taking all the capitals in their totality, further accumulation was quite pointless on the prevailing basis. Suppose there are four enterprises, of equal size but different organic compositions, in a particular branch of industry:

1) 50c : 50v

2) 40c : 60v

3) 35c : 65v

4) 25c : 75v

-------------

150c :250v

Assume that 150c represent the absolute limit of accumulation on the existing basis. At this point a crisis ensues and the companies are forced to reorganise, that is to rationalise their plants. For example companies 1 and 2 decide to merge so that the organic composition expands, say in the ratio of 7c: 3v. In the new enterprise with 90c only 38v (instead of 110) is thus used. Labour power to the value of 72v is set free; rationalisation leads to the formation of a reserve army. Once the merger is complete we have three enterprises as a result of the concentration process and a reserve army of 72v.

1) 90c: 38v

2) 35c : 65v

3) 25c : 75v

-------------

150c :178v

For the new enterprise resulting from the merger, the higher organic composition entails a restoration of its profitability even at the lower price level 2. Firstly because the higher organic composition of capital means an increase in the productivity of labour and thus a reduction in unit costs. Secondly because an increase in the productivity of labour also means a higher rate of surplus value. This increase in the rate of surplus value implies that as the other companies also decide to rationalise the total surplus value obtainable expands proportionately, quite irrespective of the fact that every year a new generation of workers is appearing on the labour market. It follows that the maximum possible limit to the accumulation of capital is pushed further back beyond the level 150c.

During the crisis there was overproduction. How was the upturn produced? Was the scale of operations reduced? On the contrary, it was expanded even further. And yet the crisis was surmounted.

That crises are surmounted although the scale of operations is extended even further is the best proof that crises do not stem from a lack of purchasing power, a shortage of consumers, or from disproportions in the individual spheres of industry. Because the crisis is rooted in a lack of valorisation it necessarily disappears once profitability is improved even if prices remain low.

The empirical evidence for this view confirms it word for word. Take the example of German shipping where, due to massive overproduction of tonnage and the ruinously low freight charges that followed, the biggest shipping companies incurred consistently heavy losses throughout the depression years 1892—4. How was this severe crisis overcome? R Schachner tells us that the depression in freight charges stimulated important changes in the technological structure of shipping. In 1894 and 1895, ‘encouraged by low construction costs, all the big companies went in for the large scale steamer’ (1903, p. 5). Due to this revolution in shipping enterprise, world shipping statistics show an increasing average size of ships: in 1893 the average was 1 418 gross register tons, in 1894 1 457 grt, in 1895 1 499 grt, in 1896 1 532 grt. The smaller companies could no longer compete on the freight market with these giant steamers and were forced to sell off their steamers at enormous losses. The position of the big shipping companies was entirely different, despite their intense competition with England. In 1895 the Hamburg—America line stated in its annual report: ‘Despite miserable freight charges, our new steamers were able to operate at a profit due to their large tonnage and their savings in (fuel) costs’ (p. 7). To overcome the crisis of overproduction of tonnage the tonnage was expanded even further, despite low prices.

The same process was repeated when, after the boom years of 1897—1900, a new crisis started in 1901. Again there was an attempt to relieve the impact of the depression through a general drive to cut costs in shipping by expanding the individual scale of operations still further (Schachner, p. 96). This happened a third time after the War. In spite of the huge losses due to the War, world shipping was afflicted by an oversupply of loading capacity. By 1926 world tonnage had increased by 31.7 per cent compared to its pre-war level.

Yet world trade had still to recover its pre-war levels, so it is not surprising that there was a state of severe depression in the world freight market. Rates declined steeply to rockbottom levels of profitability. How was this crisis overcome? Despite the massive oversupply of tonnage, international shipping converted to the latest type of vessels with a still larger scale of operations. As against an average capacity of 1 857 grt in 1914, the figure was 2 136 grt in 1925. Loading capacities increased even more sharply. Today a modern 8 000 ton steamer with a 10-knot speed consumes only 30 tons of coal per day. Prior to the War it consumed 35—6 tons per day. Yet the most significant technological change, decisive to the whole question of profitability, was the introduction of a new type of propulsion. In 1914 mechanised vessels formed just 3.1 per cent of the total world tonnage. By the end of 1924 their share was 37.6 per cent. As against the old coal-run steamers, the new mechanised ships were characterised by much higher loading capacities relative to size, by lower fuel costs and by savings in manpower. For instance on English vessels, despite a shorter working day, average crew size declined from 2.58 per grt in 1920 to 2.41 per grt in 1923.

In short, despite the trough in freight rates, the technological rationalisation of shipping restored profit levels and enabled the industry to overcome its crisis.

Because it is so recent, we hardly need to substantiate the fact that the last great depression following the German stabilisation of 1924—6 was overcome by the same methods of rationalisation — by a process of fusion and concentration, and increases in the productivity of labour through technological renovations. Profitability was revived and the crisis surmounted through increases in productivity and extensions in the scale of production. If we survey the process in its pure form over a longer period of several cycles and in abstraction from various countertendencies, it follows that prices show a declining tendency from one crisis to the next (in Figure 4, from level 1 to level 2 and so on), whereas the scale of production undergoes continuous expansion. In reality the process does not take this pure form due to the intervention of various subsidiary factors.

In a given branch of production the crisis is never overcome purely through the technological improvements within the branch itself. The capitalists also gain from the technological and organisational changes accomplished in other spheres of industry, either because these changes reduce their investment costs by cheapening basic elements of the reproductive process or because improvements in transport or monetary circulation shorten the turnover time of capital and thus increase the rate of surplus value. The more a movement of rationalisation spreads and penetrates into a whole series of new industries, the more the boom gains in intensity because improvements in one sphere of industry mean an expanding mass of surplus value in others.

a) Starting from a dynamic equilibrium the previous analysis assumed a constant rate of surplus value of 100 per cent throughout the course of accumulation. This conflicts with reality and has a purely fictitious, tentative character. It has to be modified.[1] Rising productivity cheapens commodities; in so far as this includes commodities that go into workers’ consumption, the elements of variable capital are thereby cheapened, the value of labour power therefore declines and surplus value and the rate of surplus value increase. Marx says:

hand in hand with the increasing productivity of labour, goes ... the cheapening of the labourer, therefore a higher rate of surplus value, even when the real wages are rising. The latter never rise proportionally to the productive power of labour. (1954, p. 566)

A further factor in enhancing the rate of surplus value is the rising intensity of labour that goes together with general increases in productivity. The increasing degree of exploitation of labour that flows from the general course of capitalist production constitutes a factor that weakens the breakdown tendency.

b) The ‘depression of wages below the value of labour power’ (Marx, 1959, p. 235) works in the same direction. Obviously, since the efficiency of work is going to fall, this can only be a temporary step.

Throughout the analysis we have assumed, in keeping with the hypothetical state of equilibrium, that the commodity labour power is fully employed — that there is no reserve army to begin with and consequently, like all other commodities, labour power is sold at its value. However I have shown that even on this assumption, a reserve army of labour necessarily forms at a certain level of capital accumulation due to insufficient valorisation. Beyond this point the mass of the unemployed exert a downward pressure on the level of wages so that wages fall below the value of labour power and the rate of surplus value rises. This forms a further source of increases in valorisation, and so another means of surmounting the breakdown tendency. The depression of wages below the value of labour power creates new sources of accumulation: ‘It ... transforms, within certain limits, the labourer’s necessary consumption fund into a fund for the accumulation of capital’ (Marx, 1954, p. 562).

Once this connection is clear, we have a means of gauging the complete superficiality of those theoreticians in the trade unions who argue for wage increases as a means of surmounting the crisis by expanding the internal market. As if the capitalist class is mainly interested in selling its commodities rather than the valorisation of its capital. The same holds for F Sternberg. He cites the low wages prevalent in England in the early nineteenth century as one reason ‘why the crises of this period caused far deeper convulsions in English capitalism than those of the late nineteenth century’ (1926, p. 407). Low wages, and therefore a high rate of surplus value, form one of the circumstances that mitigate crises.

In the reproduction schemes a period of production lasts one year and the working period and period of production are identical. There is no period of circulation and the working periods follow one another immediately.

The duration of the production period is the same in all spheres of production and the assumption is made that in all branches capital turns over once every year. None of these several assumptions corresponds to reality and they are intended purely for simplification. First the working period and production time are not identical in reality. Secondly, apart from the production time, there must also be a circulation time. And finally turnover time varies from one branch of production to another and is determined by the material nature of the process of production. If the analysis is to bear any correspondence to the real appearances those assumptions also have to be modified.

According to Marx the ‘difference in the period of turnover is in itself of no importance except so far as it affects the mass of surplus labour appropriated and realised by the same capital in a given time’ (1959, p. 152). The impact of turnover on the production of surplus value can be summarised by saying that during the period of time required for turnover the whole capital cannot be deployed productively for the creation of surplus value. A portion of the capital always lies fallow in the form of either money capital, commodity capital or productive capital in stock.

The capital active in the production of surplus value is always limited by this portion and the mass of surplus value obtained diminished in proportion. Marx says that the ‘shorter the period of turnover, the smaller this idle portion of capital as compared with the whole, and the larger, therefore, the appropriated surplus value, provided other conditions remain the same’ (1959, p. 70).

The reduction of turnover time means reductions of both production and circulation time. Increases in the productivity of labour are the chief means of reducing the production time. As long as technological advances in industry do not entail a simultaneous considerable enlargement of constant capital, the rate of profit will rise. Meanwhile the ‘chief means of reducing the time of circulation is improved communications’ (Marx, 1959, p. 71). The technological advances in shipbuilding mentioned above fall into this category.

The rationalisation of German railways with the introduction of the automatic pneumatic brake made possible total savings of around 100 million marks a year, mainly through reductions in personnel and major changes in the speed of freight traffic. Once shunting was mechanised so that trains could be built more quickly and cheaply, and many lines were electrified, the railway system was completely revolutionised.

Apart from improvements in transport, savings are achieved by reducing expenditure on commodity capital. Before commodities are sold they exist in the sphere of production in the shape of stock whose storage constitutes a cost The producer tries to restrict his inventory to the minimum adequate for his average demand. However this minimum also depends on the periods that different commodities need for their reproduction. With improvements in transport, storage costs can be cut as a proportion of the total volume of sales transactions. In addition such costs tend to fall relative to total output as this output becomes ‘more concentrated socially’ (Marx, 1956, p. 147).

Every crisis precipitates a general attempt at reorganisation which, among other things, attacks the existing level of storage costs. The time during which capital is confined to the form of commodity capital tends to become progressively shorter. That is, the annual turnover of capital is speeded up. This is a further means of surmounting crises. Marx says that:

the scale of reproduction will be extended or reduced commensurate with the particular speed with which that capital throws off its commodity form and assumes that of money, or with the rapidity of the sale (1956, p. 40).

Many writers argue that the programmes of expansion characteristic of the boom are impossible without an additional sum of money; that additional credit creates the boom or makes it possible. But the capitalist mechanism and its cyclical fluctuations are governed by quite different forces. I have already shown that production can be extended even if the level of prices remains constant or falls.

Nevertheless assuming a given velocity of circulation of money, additional money is required to extend the scale of production. But this is for quite different reasons than those adduced by supporters of the credit theory. We know from Marx’s description of the reproduction process that both the individual and the total social capital must split into three portions if the process of reproduction is to have any continuity. Apart from productive and commodity capital, one portion must stay in circulation in the form of money capital. The size of this money capital is historically variable. Even if it grows absolutely it declines in proportion to the total volume of sales transactions.

At any given point of time however, it is a given magnitude which can be calculated according to the law of circulation. If production is expanded then, other things being equal, the mass of money capital also has to be expanded. What is the source of this additional money capital required for expansions in the scale of reproduction?

In Chapter 15 of Capital Volume Two Marx showed how through the very mechanism of the turnover money capital is always periodically set free. While one portion of capital is tied up in production during the working period another portion is in active circulation. If the working period were equal to the circulation period the money flowing back out of circulation would be constantly redeployed in each successive working period, and vice versa, so that in this case no part of the capital successively advanced would be set free. However in all cases where the circulation period and the working period are not equal ‘a portion of the total circulating capital is set free continually and periodically at the close of each working period’ (Marx, 1956, p. 283). As the case of equality is only exceptional it follows that ‘for the aggregate social capital, so far as its circulating part is concerned, the release of capital must be the rule’ (p. 284). Thus a ‘very considerable portion of the social circulating capital, which is turned over several times a year, will therefore exist in the form of released capital during the annual turnover cycle which is set free ... the magnitude of this capital set free will grow with the scale of production the magnitude of the released capital grows with the volume of the labour process or with the scale of production’ (p. 284).

Engels thought that Marx had attached ‘unwarranted importance to a circumstance, which, in my opinion, has actually little significance. I refer to what he calls the “release” of money capital’ (1956, p. 288). This assessment of Engels appears to me to be completely off the mark. Through his analysis Marx did not merely show that large masses of money capital are periodically set free through the very mechanism of the turnover. He also explicitly refers to the fact that due to the curtailment of the periods of turnover as well as to technical changes in production and circulation - as we have seen, carried through chiefly in periods of depression — a ‘portion of the capital value advanced becomes superfluous for the operation of the entire process of social reproduction ... while the scale of production and prices remain the same’ (p. 287). This superfluous part ‘enters the money market and forms an additional portion of the capitals functioning here’ (p. 287). It follows that after every period of depression a new disposable capital stands available. This setting free of a part of the money capital also affects the valorisation of the total capital; it increases the rate of profit in the sense that the same surplus value is calculated on a reduced total capital. The setting free of a part of the money capital is thus a further means of surmounting the crisis. Marx thus shows that despite the assumption of equilibrium:

a plethora of money capital may arise ... in the sense that a definite portion of the capital value advanced becomes superfluous for the operation of the entire process of social reproduction ... and is therefore eliminated in the form of money capital -. a plethora brought about by the mere contraction of the period of turnover, while the scale of production and prices remain the same. (p. 287)

The reduction in the turnover period generates an additional mass of money capital which is used to expand the scale of reproduction further whenever a period of boom is beginning. Marx has this function in mind when he states that the ‘money capital thus released by the mere mechanism of the turnover movement ... must play an important role as soon as the credit system develops and must at the same time form one of the latter’s foundations’ (p. 286).

Up to now Marxists have drawn attention to the fact that with the general progress of capital accumulation the value of constant capital increases absolutely and relative to variable capital. Yet this phenomenon forms only one side of the accumulation process; it examines the process from its value side. However — and this cannot be emphasised enough — the reproduction process is not simply a valorisation process; it is also a labour process, producing not only values but also use values. Considered from the side of use value, increases in the productivity of labour represent not merely a devaluation of the existing capital, but also a quantitative expansion of useful things.

Earlier I referred to how rising productivity cheapens the use values consumed by workers and, as a result, raises the rate of surplus value. Now we shall examine the impact of increases in the mass of use values, through rising productivity, on the fund for accumulation. Marx proceeds from the empirical fact that:

with the development of social productivity of labour the mass of produced use values, of which the means of production form a part, grows still more. And the additional labour, through whose appropriation this additional wealth can be reconverted into capital, does not depend on the value, but on the mass of these means of production (including means of subsistence), because in the production process the labourers have nothing to do with the value, but with the use value, of the means of production. (1959, p. 218)

Increases in productivity that impinge on the material elements of productive capital, especially fixed capital, mean a higher profitability for individual capitals. The same mechanism operates when we look at the process of reproduction in its totality. Marx writes:

with respect to the total capital ... the value of the constant capital does not increase in the same proportion as its material volume. For instance, the quantity of cotton worked up by a single European spinner in a modern factory has grown tremendously compared to the quantity formerly worked up by a European spinner with a spinning wheel. Yet the value of the worked up cotton has not grown in the same proportion as its mass. The same applies to machinery and other fixed capital ... In isolated cases the mass of the elements of constant capital may even increase, while its value remains the same, or falls. (1959, p. 236)

The expansion in the mass of use values in which a given sum of value is represented is of great indirect significance for the valorisation process. With an expanded mass of the elements of production, even if their value is the same, more workers can be introduced into the productive process and in the next cycle of production these workers will be producing more value. Marx writes that as a consequence of growing productivity:

More products which may be converted into capital, whatever their exchange value, are created with the same capital and the same labour.

These products may serve to absorb additional labour, hence also additional surplus labour, and therefore create additional capital. The amount of labour which a capital can command does not depend on its value, but on the mass of raw and auxiliary materials, machinery and elements of fixed capital and necessities of life, all of which it comprises, whatever their value may be. As the mass of the labour employed, and thus of surplus labour increases, there is also a growth in the value of the reproduced capital and in the surplus value newly added to it. (p. 248)

Elsewhere Marx says:

the most important thing for the direct exploitation of labour itself is not the value of the employed means of exploitation, be they fixed capital, raw materials or auxiliary substances. In so far as they serve as means of absorbing labour, as media in or by which labour and, hence, surplus labour are materialised, the exchange value of machinery, buildings, raw materials, etc, is quite immaterial. What is ultimately essential is, on the one hand, the quantity of them technically required for combination with a certain quantity of living labour, and, on the other, their suitability, ie, not only good machinery, but also good raw and auxiliary materials. (1959, pp. 82—3)

With increases in productivity and the mass of use values, the mass of means of production (and of subsistence) which can function as means of absorbing labour expands more rapidly than the value of the accumulated capital. The means of production can therefore employ more labour and extort more surplus labour than would otherwise correspond to the accumulation of value as such. Marx says that with increases in productivity and a cheapening of labour power the:

same value in variable capital therefore sets in movement more labour power, and, therefore, more labour. The same value in constant capital is embodied in more means of production, ie, in more instruments of labour, materials of labour and auxiliary materials; it therefore also supplies more elements for the production both of use value and of value, and with these more absorbers of labour. The value of the additional capital, therefore, remaining the same or even diminishing, accelerated accumulation still takes place. Not only does the scale of reproduction materially extend, but the production of surplus value increases more rapidly than the value of the additional capital. (1954, p. 566)

This tendency for the mass of use values to expand runs parallel with the opposite tendency for constant capital to increase in relation to variable — and hence for the number of workers to decline. However these ‘two elements embraced by the process of accumulation ... are not to be regarded merely as existing side by side in repose ... They contain a contradiction which manifests itself in contradictory tendencies and phenomena. These antagonistic agencies counteract each other simultaneously’ (Marx, 1959, pp. 248—9). ‘The accumulation of capital in terms of value is slowed down by the falling rate of profit, to hasten still more the accumulation of use values, while this, in its turn, adds new momentum to accumulation in terms of value’ (p. 250).

In Table 2.2 we saw that with an increase in working population of 5 per cent a year and an expansion of constant capital of 10 per cent, the system would have to collapse in year 35. But because the mass of capital grows more rapidly in use value than in value terms, and because the employment of living labour depends not on the value but on the mass of the elements of production, it follows that to employ the working population at a given level a much smaller capital would actually suffice than shown in the table itself. Increases in productivity and the expansion of use values bound up with them react as if the accumulation of values were at a lower or more initial stage. They represent a process of economic rejuvenation. The life span of accumulation is thus prolonged. But this only means that the breakdown is postponed, which, ‘again shows that the same influences which tend to make the rate of profit fall, also moderate the effects of this tendency’ (p. 236).

It is thus completely inadequate to examine the process of reproduction purely from the side of value. We can see what an important role use value plays in this process. Marx himself always tackled the capitalist mechanism from both sides — value as well as use value.

Critics have often pointed out that according to Marx’s prognosis ‘competition rages like a plague among the capitalists themselves, eliminates them on a massive scale until eventually only a tiny number of capitalist magnates survive’ (Oppenheimer, 1927, p. 499). Sternberg repeats the same point. Having portrayed Marx’s argument in this fashion it is easy to pronounce that it is not substantiated by the concrete tendencies of historical development.

But this overlooks the essential point of Marx’s methodological procedure. Marx’s schemes deliberately simplify — they show only two spheres of production within which individual capitals progressively succumb to concentration. On this assumption the number of capitalists progressively declines. But the assumption that there are only two spheres of production is fictitious and it has to be modified so as to correspond with empirical reality. Marx shows that there is a continual penetration by capital into new spheres in which:

portions of the original capitals disengage themselves and function as new and independent capitals. Besides other causes, the division of property, within capitalist families, plays a great part in this. With the accumulation of capital, therefore, the number of capitalists grows to a greater or lesser extent (1954, p. 586)

The concentration of capital is thus supplemented by the opposite tendency of its fragmentation. In this way ‘the increase of each functioning capital is thwarted by the formation of new and the sub-division of old capitals (p. 586). Because the minimum amount of capital required for business in spheres with a higher organic composition is very high and is growing continuously, smaller capitals ‘crowd into spheres of production which Modern Industry has only sporadically or incompletely got hold of’ (p. 587). These are naturally spheres with a lower organic composition where a relatively larger mass of workers is employed.

If a new branch of production comes into being employing a relatively large mass of living labour — in which therefore the composition of capital is far below the average composition which governs the average profit — a larger mass of surplus value will be produced in this branch. Marx says that competition ‘can level this out, only through the raising of the general level (of profit), because capital on the whole realises, sets in motion, a greater quantity of unpaid surplus labour’ (1969, p. 435). Obviously this must also restrain the breakdown tendency. On the one hand the lower organic composition of capital raises the rate of profit, on the other the formation of new spheres of production makes possible further investment of capital.

In this way a cyclical movement evolves — the self-expanding capital searches out new investment possibilities while new inventions create such possibilities, new spheres of industry develop suddenly, superfluous capital is reabsorbed, and gradually there is a new accumulation of capital which is destined to become superfluous on an ever larger scale, and so on. This accounts for the importance of:

new offshoots of capital seeking to find an independent place for themselves ... as soon as formation of capital were to fall into the hands of a few established big capitals, for which the mass of profits compensates for the falling rate of profit, the vital flame of production would be altogether extinguished. It would die out. (Marx,1959, p. 259)

British capitalism is deeply symptomatic of these processes. While the traditional industrial centres of the North, of Scotland and Wales have been in a chronic crisis, a whole series of new industries have begun to spring up in the South, in the Midlands and in the areas surrounding London. A report published by the inspector-general of factories shows that these industries have a much lower organic composition of capital. For example around London, apart from a few car-assembly plants, there are factories producing bandages, minor electrical fittings, bedsteads, bedspreads, ice-creams, mixed pickles, cardboard boxes and pencils. Among the few newer industries with a fairly high organic composition are rayon and automobiles. The latter involves some 14 500 units, over half of which are repair shops scattered across the country. According to data released by the Ministry of Labour (1926) the number of workers employed in the new industries increased by 14 per cent in the space of three years (1923—6), while those employed in the older industries like coalmining and shipbuilding declined by 7.5 per cent.

Earlier Britain could afford to import small-scale stuff from the Continent and Japan, whereas now it has to produce it itself. Even if the development of such industries does relieve the general impact of the economic depression it cannot compensate for the catastrophic consequences of the decline of the older branches which formed the basis of Britain’s domination. In fact the new industries employ a total of only 700 000 workers, whereas the majority are still in the traditional branches like coal, textiles, shipbuilding and so on.

A model of pure capitalism where there are only two classes, capitalists and workers, assumes that agriculture forms only a branch of industry completely under the sway of capital. In other words we abstract from the category of groundrent, from the existence of landlords. But how are the results of this analysis modified once this assumption is dropped?

Modern, purely capitalist, groundrent is simply a tax levied on the profits of capital by the landlord. To the landlord ‘the land merely represents a certain money assessment which he collects by virtue of his monopoly from the industrial capitalist’ (Marx, 1959, p. 618). When Marx refers to the levelling of surplus value to average profit he says:

This appropriation and distribution of surplus value, or surplus product, on the part of capital, however, has its barrier in landed property. Just as the operating capitalist pumps surplus labour, and thereby surplus value and surplus product in the form of profit, out of the labourer, so the landlord in turn pumps a portion of this surplus value ... out of the capitalist in the form of rent. (p. 820)

Rent thus plays a role in depressing the level of the average rate of profit, it speeds up the breakdown tendency of capitalism. Spokesmen of capitalism have always been hostile to groundrent because ‘landed property differs from other kinds of property in that it appears superfluous and harmful at a certain stage of development, even from the point of view of capitalism’ (p. 622). Ricardo’s writings were directed against the interests of the landlords and their supporters. The land reform movements of the latter part of the nineteenth century sprang fundamentally from the same source.

Commercial profit has the same impact on the breakdown of capitalism as groundrent Earlier we assumed that merchant’s capital does not intervene in the formation of the general rate of profit. Again, this assumption has a purely methodological value; it has to be modified. Marx says that ‘in the case of merchant’s capital we are dealing with a capital which shares in the profit without participating in its production. Hence, it is now necessary to supplement our earlier exposition’ (1959, p. 284). Commercial profit is a ‘deduction from the profit of industrial capital. It follows [that] the larger the merchant’s capital in proportion to the industrial capital, the smaller the rate of industrial profit, and vice versa’ (p. 286). Clearly this will intensify and speed up the breakdown of capitalism.

In periods of crisis this struggle against traders is a means of improving the conditions of valorisation capital. In his report on the American crisis, Professor Hirsch has shown that in America the elimination of large-scale traders by rural cooperatives in grain, fruit and milk has assumed massive proportions, with cooperative sales accounting for as much as 20 per cent of the total sales of US agricultural produce. The cotton farmers of the north are likewise engaged in a struggle to eliminate intermediaries and supply the spinners directly.

This movement acquires its most powerful expression in the drive by the modern cartels and trusts to increase profitability by reducing the costs of sales and import transactions through a centralisation and elimination of intermediary trade. According to Hilferding its capacity to wipe out the trader is one of the basic reasons for the superiority of the combined enterprise. With the rapid advance of cartelisation in the iron and steel industry, the significance of commercial capital has declined. There is a striking tendency to wipe out intermediary trade as the mining and production stages are integrated vertically into a single enterprise, so that no profit is diverted to commercial capital at any single stage of the process. This is the realisation of Rockefeller’s maxim; ‘pay a profit to nobody’. Commercial capital is either left to supplying small customers or forced into a position of dependence on industrial capital. ‘The development of large-scale industrial concerns, or the formation of monopolies’, says T Vogelstein:

has dethroned the princely merchant and transformed him into a pure agent or stipendiary of the monopolies ... This world of monopolies is ridding itself of every vestige of commerce ... By transferring sales transactions to the syndicates ... the industrial concern reduces purely commercial activity to a minimum and leaves this to a few people in the head office or to individual trading concerns affiliated to itself. (1914, p. 243)

The formation of their own export organisations by the larger associations and concerns is yet another example of the tendency to wipe out independent large-scale trade. In copper a system of trading survives but no longer as an independent function; the system is intricately connected with the producers. Dyestuffs and electricals are two industries with their own sales organisations abroad. According to the calculations made by E Rosenbaum of Germany’s total imports in 1926, around 48.3 per cent were direct, that is, transacted without the mediation of any trading concerns. In the case of textile raw materials the figure was 50 per cent and in ores and metals as high as 90 per cent (1928, pp. 130 and 146).

The squeeze on commercial profit to enhance the average rate of profit on industrial capital is a product of the growing barriers to valorisation that arise in the course of capital accumulation. Therefore as the level of accumulation advances, the tendency to eliminate commercial capital intensifies.

However the squeeze on commercial profit is not tantamount to a cessation of commercial activity. The latter cannot be done away with under capitalism because commercial agents fulfil basic functions of industrial capital in the process of its circulation, namely, its function of realising values. In this respect they are simply representatives of the industrial capitalist. Marx says that:

In the production of commodities, circulation is just as necessary as production itself, so that circulation agents are just as much needed as production agents. The process of reproduction includes both functions of capital, therefore it includes the necessity of having representatives of these functions, either in the person of the capitalist himself or of wage labourers, his agents. (1956, pp. 129—30)

Despite the tendency for commercial profit to be eliminated, commercial functions gain in importance as capitalism develops. This is regardless of whether they are represented by individual merchants, trade organisations, cooperatives or industrial trusts and concerns. Prior to capitalism there was no large-scale commercialisation of the product of labour: ‘The extent to which products enter trade and go through the merchants’ hands depends on the mode of production, and reaches its maximum in the ultimate development of capitalist production, where the product is produced solely as a commodity’ (Marx, 1959, p. 325). It follows that the share of commerce in the overall occupational structure must expand. There is a growing number of commercial businesses and commercial employees. A new middle stratum of commercial agents, commercial employees, secretaries, accountants, cashiers emerges.

The question arises — what impact does the existence of this new middle stratum have on the course of the capitalist reproduction process? Can it reduce the severity of capitalist crises and weaken the breakdown tendency, as the reformists have argued ever since Bernstein? Marx points to the different character of this middle stratum which arises on the foundations of capitalist production:

The outlay for these [commercial wage-workers], although made in the form of wages, differs from the variable capital laid out in purchasing productive labour. It increases the outlay of the industrial capitalist, the mass of the capital to be advanced, without directly increasing surplus value. Because it is an outlay for labour employed solely in realising value already created. Like every other outlay of this kind, it reduces the rate of profit because the advanced capital increases, but not the surplus value. (1959, p. 299)

Due to the variable capital expended on these commercial wage workers, the accumulation fund available for the employment of more productive workers is reduced.

A part of the variable capital must be laid out in the purchase of this labour power functioning only in circulation. This advance of capital creates neither product nor value. It proportionately reduces the dimensions in which the advanced capital functions productively. (Marx, 1956, p. 136)

The rate of valorisation of the total social capital is thereby diminished and the breakdown tendency intensified, quite regardless of the fact that these middle strata may initially consolidate the political domination of capital. As these middle strata grow the breakdown is speeded up. As long as the mass of surplus value is growing absolutely this is not visible. But once there is a lack of valorisation due to the advance of accumulation this fact is shown all the more sharply.

The term third persons is used by Marx in a double sense. Sometimes he refers to the independent, small-scale producers who are remnants of earlier forms of production. They are not intrinsically connected with capitalism as such and so must be excluded from any analysis of its inner nature. We shall see later how far these elements can and do affect capitalist production through the mediation of the world market. Secondly Marx understands by third persons bureaucrats, the professional strata, rent receivers and so on, who exist on the foundations of capitalism but do not participate in material production either directly or indirectly and are therefore unproductive from the standpoint of such production. They do not enlarge the mass of actual products but, on the contrary, reduce it by their consumption, even if they perform various valuable and necessary services by way of repayment. The income of these people is not obtained by virtue of their control of capital, so it is not an income got without work.

However important these services may be they are not embodied in products or values. In so far as the performers of these services consume commodities they depend on those persons who participate in material production. From the standpoint of material production their incomes are derivative. Marx writes:

All members of society not directly engaged in reproduction, with or without labour, can obtain their share of the annual commodity product — in other words, their articles of consumption — primarily out of the hands of those classes to which the product first accrues — productive workers, industrial capitalists and landlords. To that extent their revenues are materially derived from wages (of the productive labourers), profit and rent, and appear therefore as derivative vis-à-vis those primary revenues. (1956, p. 376)

This group of third persons which was initially excluded from the analysis of pure capitalism has to be reintroduced at a later stage. Marx points out that society ‘by no means consists of only two classes, workers and industrial capitalists, and ... therefore consumers and producers are not identical categories’ (1969, p. 493). The:

first category, that of the consumers ... is much broader than the second category [producers], and therefore the way in which they spend their revenue, and the very size of the revenue give rise to very considerable modifications in the economy and particularly in the circulation and reproduction process of capital. (p. 493)

What significance does the existence of these people have for the reproduction and accumulation of capital? In so far as their material incomes are dependent incomes — that is, drawn from the capitalists — we are dealing with groups which are, from the standpoint of production, pure consumers. As long as this consumption by third persons is not sustained directly at the cost of the working class, surplus value or the fund for accumulation is reduced. Of course these groups perform various services in return, but the non-material character of such services makes it impossible for them to be used for the accumulation of capital. The physical nature of the commodity is a necessary precondition of its accumulation. Values enter the circulation of commodities, and thereby represent an accumulation of capital, only insofar as they acquire a materialised form.

Because the services of third persons are of a non-material character, they contribute nothing to the accumulation of capital. However their consumption reduces the accumulation fund. The larger this class the greater the deduction from the fund for accumulation. In Germany in 1925 the services of such groups were valued at six billion marks, which amounts to 11 per cent of the total national income. In Britain, where there is a large number of such persons, the tempo of accumulation will have to be slower. In America, where their proportion is low, it can be much more rapid. If the number of these third persons were cut down, the breakdown of capitalism could be postponed. But there are several limits to any such process, in the sense that it would entail a cut in the standard of living of the wealthier classes.

Along with Bauer we assumed that each year there are technological changes going on which mean that constant capital is expanding more rapidly than variable capital. However production is not always expanded on the basis of a higher organic composition. Capitalists may expand production on the existing technological basis for an extended period of time.

In such cases we are dealing with simple accumulation where the growth of constant capital proceeds in step with variable capital — the expansion of capital exerts a proportional attraction on workers. Of course, the technological foundations of capitalism are being constantly improved and the organic composition is always changing. Nevertheless these changes are ‘continually interrupted by periods of rest, during which there is a mere quantitative extension of factories on the existing technical basis’ (Marx, 1954, p. 423).

As the accumulation of capital advances these periods of rest become progressively shorter. However to the extent that such periods of rest occur, they imply a weakening of the breakdown tendency. Marx writes:

This constant expansion of capital, hence also an expansion of production, on the basis of the old method of production which goes quietly on while new methods are already being introduced at its side, is another reason why the rate of profit does not fall as much as the total capital of society grows. (1959, p. 263)

We shall see that as world market antagonisms intensify, technological superiority is the sole means of surviving on the world market. The sharper the struggle on the world market the greater the compulsion behind technological changes, so that the intermediate pauses are shortened. Gradually this counteracting factor becomes less and less important.

The assumption of constant values is one of the many underlying the reproduction scheme of Marx. Bauer adopts this assumption in two senses: (i) the value of the constant capital used up in the process of production is transferred intact to the product; (ii) the values created in each cycle of production are accumulated in the next cycle without undergoing any quantitative changes. (Some values are of course destroyed in consumption.) This constancy is postulated although Bauer’s scheme presupposes continuous technological progress. He does not notice the contradiction.

Technological progress means that since commodities are created with a smaller expenditure of labour their value falls. This is not only true of the newly produced commodities. The fall in value reacts back on the commodities that are still on the market but which were produced under the older methods, involving a greater expenditure of labour time. These commodities are devalued.

There is no trace of this phenomenon in Bauer’s scheme. He refers to devaluations but this is only due to periodic overproduction. The implication is that if the system were in equilibrium there would be no devaluations — the value relations of any given point of time would survive indefinitely. Things are quite different in Marx. Devaluation necessarily flows out of the mechanism of capital even in its ideal or normal course. It is a necessary consequence of continual improvements in technology, of the fact that labour time is the measure of exchange value.

It follows that the assumption of constant values has a purely provisional character. The question arises — how is the law of accumulation and breakdown modified in its workings when the assumption is dropped? Until now this problem has never been posed. Both Bauer and Tugan realised that holding values constant is a simplifying assumption. But neither modified this assumption. For this reason their models of reproduction are completely unrealistic fictions which cannot reflect or explain the actual course of capitalist reproduction.

Devaluation of capital goes hand in hand with the fall in the rate of profit and is crucial for explaining the concentration and centralisation of capital that accompanies this fall.

We have seen how the accumulation process encounters its ultimate limits in insufficient valorisation. The further continuation of capital depends on restoring the conditions of valorisation. These conditions can only be secured if a) relative surplus value is increased orb) the value of the constant capital is reduced ‘so that the commodities which enter either the reproduction of labour-power, or into the elements of constant capital, are cheapened. Both imply a depreciation of the existing capital’ (Marx, 1959, p. 248). This depreciation does not come about as a consequence of overproduction but in the normal course of capitalist accumulation — as a result of constant improvements in technology. Advances in technology thus entail ‘periodical depreciation of existing capital — one of the means immanent in capitalist production to check the fall of the rate of profit and hasten accumulation of capital value through formation of new capital’ (p. 249).

The result of the devaluation of capital is reflected in the fact that a given mass of means of production represents a smaller value. The result is analogous to that which arises from growing productivity — cheapening of the elements of production and a faster growth of the mass of use values as compared with the mass of value. However in the case of rising productivity the elements of production actually start off cheaper whereas here we are dealing with a case where the elements of production produced at a given value are only subsequently devalued.

With devaluation the technological composition of capital remains the same while its value composition declines. Both before and after devaluation the same quantity of labour is required to set in motion the same mass of means of production and to produce the same quantity of surplus value.

But because the value of the constant capital has declined this quantity of surplus value is calculated on a reduced capital value. The rate of valorisation is thereby increased and so the breakdown is postponed for some time. In terms of Bauer’s scheme, periodic devaluation of capital would mean that the accumulated capital represents a smaller value magnitude than shown by the figures there and would, for example, only reach the level of year 20 as late as year 36.

In other words, however much devaluation of capital may devastate the individual capitalist in periods of crisis, they are a safety valve for the capitalist class as a whole. For the system devaluation of capital is a means of prolonging its life span, of defusing the dangers that threaten to explode the entire mechanism. The individual is thus sacrificed in the interest of the species.

The devaluation of accumulated capital takes various forms. Initially Marx deals with the case of periodic devaluation due to technological changes. In this case the value of the existing capital is diminished while the mass of production remains the same. The same effect however, is produced when the apparatus of reproduction is used up or destroyed in terms of value as well as use value through wars, revolutions, habitual use without simultaneous reproduction, etc. For a given economy the effect of capital devaluation is the same as if the accumulation of capital were to find itself at a lower stage of development. In this sense it creates a greater scope for the accumulation of capital.

The specific function of wars in the capitalist mechanism is only explicable in these terms. Far from being an obstacle to the development of capitalism or a factor which accelerates the breakdown, as Kautsky and other Marxists have supposed, the destructions and devaluations of war are a means of warding off the imminent collapse, of creating a breathing space for the accumulation of capital. For example it cost Britain £23.5 million to suppress the Indian uprising of 1857—8 and another £77.5 million to fight the Crimean War. These capital losses relieved the overtense situation of British capitalism and opened up new room for her expansion. This is even more true of the capital losses and devaluations to follow in the aftermath of the 1914—18 war. According to W Woytinsky, ‘around 35 per cent of the wealth of mankind was destroyed and squandered in the four years’ (1925, pp. 197—8). Because the population of the major European countries simultaneously expanded, despite war losses, a larger valorisation base confronted a reduced capital, and this created new scope for accumulation.

Kautsky was completely wrong to have supposed that the catastrophe of the world war would inevitably lead to the breakdown of capitalism and then, when no such thing happened, to have gone on to deny the inevitability of the breakdown as such. From the Marxist theory of accumulation it follows that war and the destruction of capital values bound up with it weaken the breakdown and necessarily provide a new impetus to the accumulation of capital. Luxemburg’s conception is equally wrong: ‘From the purely economic point of view, militarism is a pre-eminent means for the realisation of surplus-value; it is in itself a sphere of accumulation’ (1968, p. 454).

This is how things may appear from the standpoint of individual capital as military supplies have always been the occasion for rapid enrichment. But from the standpoint of the total capital, militarism is a sphere of unproductive consumption. Instead of being saved, values are pulverised. Far from being a sphere of accumulation, militarism slows down accumulation. By means of indirect taxation a major share of the income of the working class which might have gone into the hands of the capitalists as surplus value is seized by the state and spent mainly for unproductive purposes.

Among the factors that counteract the breakdown Marx includes the fact that a progressively larger part of social capital takes the form of share capital:

these capitals, although invested in large productive enterprises, yield only large or small amounts of interest, so-called dividends, once costs have been deducted ... These do not therefore go into levelling the rate of profit, because they yield a lower than average rate of profit. If they did enter into it, the general rate of profit would fall much lower. (1959, p. 240)

In the scheme, where the entire capitalist class is treated as a single entity, the social surplus value is divided among the portions a~ and a~ required for accumulation, and k which is available to the capitalists as consumption. Now suppose there were capitalists (owners of shares, bonds, debentures, etc.) who did not consume the whole of k, but generally only a smaller portion of it, then the amount remaining for accumulation would be larger than the sum a~ + a~. This could then form a reserve fund for the purposes of accumulation, which would make it possible for accumulation to last longer than is the case in the scheme. The fact that many strata of capitalists are confined strictly to this normal interest, or dividend, is thus one of the reasons why the breakdown tendency operates with less force. This is also the basic reason why Germany, following the example of Britain where this happened much earlier, has seen a sharp increase in the bonds of the industrial societies.

Bauer argued that crises only stem from a temporary discrepancy between the scale of the productive apparatus and increases in population. The crisis automatically adjusts the scale of production to the size of population and is then overcome. Luxemburg produced a brilliant refutation of this harmonist theory (1972, pp. 107—39). She showed that in the decades prior to the War the tempo of accumulation was more rapid than the slow rate at which the population increased in various countries. Bauer’s observation that ‘under capitalism there is a tendency for the accumulation of capital to adjust to the growth of population’ (1913, p. 871) is thus incompatible with the facts. In the fifty years from 1870 to 1920, the US population increased by around 172 per cent, while the accumulation of capital in industry expanded by more than 2 600 per cent.

However Luxemburg’s critique, which is perfectly valid against Bauer, makes the basic mistake of seeing population only as a market for capitalist commodities: ‘It is obvious that the annual increase of ‘mankind’ is relevant for capitalism only to the extent that mankind consumes capitalist commodities’ (1972, p. 111). She sees in population a limit to the accumulation of capital in the sense that it cannot provide a sufficient market for those commodities.

My own view is diametrically opposed to both Bauer’s and Luxemburg’s. Against Bauer, and using his own reproduction scheme, I have shown that from a certain stage — despite increases in population — an overaccumulation of capital results from the very essence of capital accumulation. Accumulation proceeds, and must proceed, faster than population grows so that the valorisation base grows progressively smaller in relation to the rapidly accumulating capital and finally dries up. From this it follows that if capital succeeds in enlarging the valorisation base, or the number of workers employed, there will be a larger mass of obtainable surplus value — a factor which will weaken the breakdown tendency. Therefore there is a perfectly comprehensible tendency for capital to employ the maximum possible number of workers. This does not in the least contradict the other tendency of capital of ‘employing as little labour as possible in proportion to the invested capital’ (Marx, 1959, p. 232). This is because the mass of surplus value depends not merely on the number of labourers employed — at a given rate of surplus value — but on raising the rate of surplus value through increases in the amount of means of production relative to living labour applied in the production process.

From this it follows that with ‘a sufficient accumulation of capital, the production of surplus value is only limited by the labouring population if the rate of surplus value ... is given’ (Marx, 1959, p. 243). Therefore population does form a limit on accumulation, but not in the sense intended by Luxemburg. If population expands the interval prior to absolute overaccumulation is correspondingly longer. This is what Marx means when he writes:

If accumulation is to be a steady, continuous process, then this absolute growth in population - although it may be decreasing in relation to the capital employed — is a necessary condition. An increasing population appears to be the basis of accumulation as a continuous process (1969, p. 477).

The tendency to employ the largest possible number of productive workers is already contained in the very concept of capital as a production of surplus value and surplus labour.

Oppenheimer’s criticism, that Marx was forced to admit that despite the overall displacement of workers their total number grows, is really unfounded and meaningless. Capital accumulation is only possible if it succeeds in creating an expanded valorisation base for the growing capital. For example at the low degree of accumulation which survived in Germany up to the end of the 1880s the nascent large-scale industry failed to absorb the entire working population. Emigration became necessary to contain this situation. In the decade 1871—80 some 622 914 persons emigrated abroad from the country. In the following decade this number rose to 1 342 423. But with the rapid upsurge of industrialisation and the accelerated tempo of accumulation in the 1890s, emigration ceased and even gave way to immigration from Poland and Italy into the industrial areas of the West. The absorption of these additional labour powers provided the basis for producing the surplus value required for the valorisation of the expanded capital.

Natural increases in urban population and migration from the countryside were insufficient. This was the case despite continuous intensification of labour which meant that the mass of exploited labour was growing faster than the number of exploited workers. A shortage of labour power persisted despite the recruitment of new workers and the reabsorption of workers displaced by the increasing mechanisation of work processes and rising organic composition of capital. After the 1907 crisis capital was compelled to seek out an expanded valorisation base by intensifying the incorporation of women workers. This had the additional advantage of being cheaper. In a penetrating account of the German economy A Feiler tells us:

It became increasingly clear that the rapid expansion of female labour which had characterised the depression years of 1908 and 1909 was not some passing phenomenon that would vanish once the rate of employment restabilised. It survived the depression years into the boom. The number of women workers continued to rise. In the five years from 1905 to 1910... the number increased by 33 per cent. This trend intensified in the years that followed. The number of women employed in factories and offices increased much more rapidly than the number of men. This was a revolution pure and simple ... At the end of 1913 there were as many employed women in Germany as employed men. (1914, p. 86)