From International Socialism 2 : 58, Spring 1993, pp. 3–57.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Marxists’ Internet Archive.

The beginning of the 1990s has seen the third major international economic crisis in 18 years. By late 1992 what had begun as a slowdown in growth rates of English speaking countries two years earlier had spread to involve most of Europe and Japan. The countries of eastern Europe and the former USSR were also in deep crisis, with slumps in output of 30 or 40 percent. In the whole world there seemed only one little spark of light for defenders of the existing system – the pacific rim Newly Industrialising Countries (NICs [A]) of Taiwan, South Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong, Thailand and, increasingly, south east China.

There could not have been a greater contrast with the situation only five years before. In the summer of 1987 the talk everywhere was of an apparently endless boom – and not only on the Thatcherite right. In Britain Marxism Today, the monthly magazine of the dying Communist Party, enthused about the dynamism of the capitalist system and its boomtime fads and fashions, while the Labour Party rewrote its programme to proclaim that the market was the best way of organising the economy and its leading figures spoke of the need to ‘leapfrog over Thatcherism’. [1] Even two years later the fashionable wisdom was that the market had an unlimited capacity to solve humanity’s problems. If only state ‘interference’ was eliminated from the eastern European economies they would flourish as the West European economies had flourished in the 1950s and 1960s. In particular, East Germany was to experience a ‘second German economic miracle.’

Yet within 12 months the economies of the US and Britain were in crisis, and this spread like a plague to afflict all the major advanced economies. And there was no sign of the promised miracle in eastern Europe as production and living standards plunged and unemployment and inflation soared. The crisis has varied in its intensity from country to country. In some (Britain [2], Japan) it proved to be more serious than that of the early 1980s. In others (especially the US), the fall in output has been less than ten years before, but persisted much longer. In any case, the crisis has been a serious blow for the world system, not just materially but also ideologically. Supporters of the system had been able to blame the crises of the mid-1970s and the early 1980s on external factors – particularly the success of the OPEC countries in forcing up the price of oil. There has been no such excuse for the crisis of the early 1990s: the surge in the oil price expected at the time of the second Gulf War early in 1991 simply did not take place. Yet the crisis continued to develop. Its source had to be internal to the workings of the advanced capitalist economies themselves – but how?

There is a Marxist account of capitalism which sees deepening crises as an intrinsic feature of the system. It is an account which is usually dismissed out of hand by mainstream economists. Typically, someone as critical of 1980s Thatcherite economics as financial journalist William Keegan can reject the Marxist account as based on ‘an obsolete economic textbook which was itself written during the early, faltering phase of unreformed capitalism’ [3], and quote, with enthusiasm, the denunciation of the Marxist approach by the French economist Marjolin: ‘A modicum of experience and some knowledge of history was enough to cast doubt on the [Marxist] theory of an inevitable decline of capitalism owing to a falling rate of profit.’ [4]

Even on the socialist left the Marxist account has often been rejected – for instance in the 1970s by Andrew Glynn, Bob Sutcliffe, John Harrison, Paul Sweezy and others. [5] Yet, properly understood, the basic account provided by Marx explains the recurrence of crises in a way in which no other can. [6]

The account rests upon grasping that the dynamic of capitalist accumulation contains within it an irresolvable contradiction. The only source of value and surplus value for the system as a whole is labour. Yet each individual capitalist can increase his own competitiveness (and therefore his share of total surplus value) through increasing the productivity of his workers if he (or occasionally she) expands investment in means of production more rapidly than his workforce. So there is a tendency for the process of capital accumulation to involve a much more rapid expansion of investment in capital than in labour, although this is the source of value – and, therefore, of profit. The outcome will be, inevitably, a growth in the ratio of capital investment to profit. As a consequence, the ratio of profit to investment – the rate of profit – will fall. Yet this is the driving force behind accumulation.

In other words, the very success of capitalism at accumulating leads to problems for further accumulation. Eventually the competitive drive of capitalists to keep ahead of other capitalists results in a massive scale of new investment which cannot be sustained by the rate of profit. If some capitalists are to make an adequate profit it can only be at the expense of other capitalists who are driven out of business. The drive to accumulate leads inevitably to crises. And the greater the scale of past accumulation, the deeper the crises will be.

This, it should be stressed, is an abstract account of the most general trends in the capitalist system. You cannot draw from it immediate conclusions about the concrete behaviour of the economy at any individual point in space and time. You have first to look at how the general trends interact with a range of other factors. [7] Marx himself was fully aware of this, and built into his account what he called ‘countervailing tendencies’. Two were of central importance. Firstly, capital accumulation increased the productivity of labour and so cut the cost of providing workers with a livelihood. Whereas in the past it might have taken three hours of work to produce enough value to sustain the average workers’ living standard, now it might take only two. The capitalist could increase the proportion of each individual worker’s labour that went into surplus value, even if the worker’s living standard was not reduced. Such an increase in the rate of exploitation could counteract some of the downward pressures on the rate of profit: the total number of workers might not grow as fast as total investment, but each worker would produce more surplus value.

Secondly, the increase in the productivity of labour meant there was a continual fall in the amount of labour time – and therefore of value – needed to produce each unit of plant, equipment or raw materials. The value of old accumulations of means of production was reduced as their replacement cost fell, causing the expansion of investment in value terms to be rather slower than the expansion in material terms, so diminishing to some extent the tendency for the value of investment to outstrip the growth in surplus value.

This in itself did not automatically solve the problem capitalists faced with the rate of profit. To survive in business they had to recoup, with a profit, the full cost of their past investments, and if technological advance meant these investments were worth, say, half what they had been previously, they had to pay for writing off that sum out of their gross profits. What they gained on the swings they lost on the roundabouts, with ‘depreciation’ of capital causing them as big a headache as a straightforward fall in the rate of profit. [8] However, such depreciation could ease the pressure on the capitalist system as a whole, if the burden of paying for it fell on some capitalists, who were driven out of business, but not by those who remained. This is precisely what happened with each crisis.

Different firms are always affected in different ways by the frenetic expansions and contractions of demand that characterise capitalist development. Some, for instance, invest early in a boom – and then incur losses because they find their equipment is not as up to date as their rivals’ plant by the high point of the boom; others invest late in the boom, with the most modern equipment, but do not get the chance to put it to profitable use in the face of the recession. Or, again, some manufacturing firms see their raw material costs soar and their profits decline as the boom peaks; others, raw material producers, see their profits rise at precisely this point.

The downward trend in the rate of profit accentuates the trend towards periodic crises. But the crisis in turn, by hitting different firms differently, ensures that some firms are driven out of business while others continue to survive. Those that die bear many of the costs of depreciation for the system as whole, making it possible for those that live on to do so with lower capital costs and eventually higher rates of profit than would otherwise be the case. Marx held that these factors would mitigate the tendency of the rate of profit to fall in the long term, over many booms and slumps. But he also argued they could not stop it completely.

First there were limitations to the ability of a rising rate of exploitation to offset the declining rate of profit. However great the increase in the amount of surplus value obtained from each worker, Marx pointed out, there was a limit to it: the total length of the working day. But there was no limit to the possibilities for expansion of investment in means of production. A point was bound to be reached at which capitalists could only make marginal gains from further increases in the rate of exploitation. Yet there was nothing to stop the ratio of capital investment to labour continuing its upward trend, and causing downward pressure on the rate of profit. In other words, raising the rate of exploitation could only be a limited, short term option for dealing with falling profit rates.

Second, Marx believed his other ‘counter-tendency’ – the depreciation and the writing off of capital through crises – could not stop the long term rise in the ratio of capital investment to labour. His own arguments on this were not as clear as those about the limited impact of raising the rate of exploitation. But it is not difficult to fill in the gaps in his argument by looking at the impact of another trend he located within capitalism – the tendency he labelled the ‘concentration and centralisation of capital’. Each crisis involves the wiping out of some individual capitals. So over time the system comes to be dominated by an ever smaller number of ever larger capitals – something which is absolutely evident today as a few multinationals dominate each industry within both national and world markets. But if one of these giants goes bust it has a very different impact on the rest of the system to that of the relatively small firms of Marx’s time going bust. Each is so big that its collapse has a devastating impact on much more competitive and profitable firms. At a stroke they lose markets that are profitable for themselves and risk following it into bankruptcy themselves. Instead of the wiping out of uncompetitive firms automatically clearing the ground for profitable expansion by other firms, the crisis can suck them down into a black hole of spreading bankruptcy.

Such considerations can explain, for example, why the crisis of the system which began in 1929 did not automatically rectify itself by 1931 but rather grew deeper, spreading from one section of capital to another, and only finally came to an end when states intervened to override market forces in the interests of militarisation. They can also explain many of the features of the crises of the last 20 years.

In applying Marx’s model under conditions of modem capitalism there is another important point to take into account. In his model value created in one round of production feeds back into accumulation in the next round, either as new means and materials of production or by providing for the consumption of value-producing workers. He barely considered the impact on the development of the system of flows of value that did not feed back into accumulation. Yet various such flows have been very important in the history of capitalism over the last century, with the massive growth of non-productive activities like advertising, sales promotion and war.

These all have the effect of using up value that would otherwise have been available for productive accumulation – and which would, in that case, have increased the pressure for investment to grow much more rapidly than the productive labour force and for profit rates to fall. As the German Marxist Henryk Grossman noted of arms expenditure [9] 65 years ago:

Far from being an obstacle to the development of capitalism or a factor which accelerates the breakdown ... the destruction and devaluations of war are a means of warding off imminent collapse, of creating a breathing space for capital accumulation. For example, it cost Britain £23.5 million to suppress the Indian uprising of 1857–8 and another £77.5 million to fight the Crimean War. These capital losses relieved the overtense situation of British capitalism and opened up new room for her expansion. This is even more true of the capital losses and devaluations to follow in the aftermath of the 1914–18 war ...

From the standpoint of total capital, militarism is a sphere of unproductive consumption. Instead of being saved, values are pulverised. Far from being a sphere of accumulation, militarism slows down accumulation. By means of indirect taxation a major share of the income of the working classes which might have gone into the hands of the capitalists as surplus value is seized by the state and spent mainly on unproductive purposes. [10]

This insight was used by W.T. Oakes (T.N. Vance) in the 1940s and 1950s and by Mike Kidron in the 1960s and 1970s to explain how capitalism was able to accumulate without immediately hitting a crisis of profitability in the decades after the outbreak of the Second World War. [11] Arms spending could not put off the crisis indefinitely, however. The burden of the spending fell disproportionately on certain countries (those of the US and the USSR in particular), allowing the capitalists of other countries to invest proportionately more in productive industry and, over time, to out-compete them. And this was bound to force the big arms spenders to cut back their own military budgets in a way that reduced the stability of the world economy as a whole. What is more, once profit rates began to fall, the cost of arms exacerbated the problems individual capitals had in finding the surplus value they needed if any accumulation at all was to take place. From being a boon to the world system, arms spending became an increasing burden.

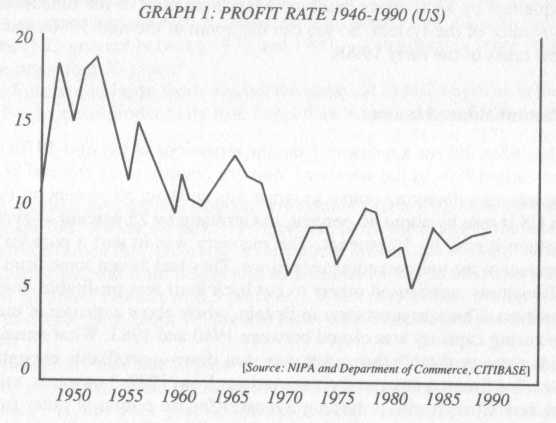

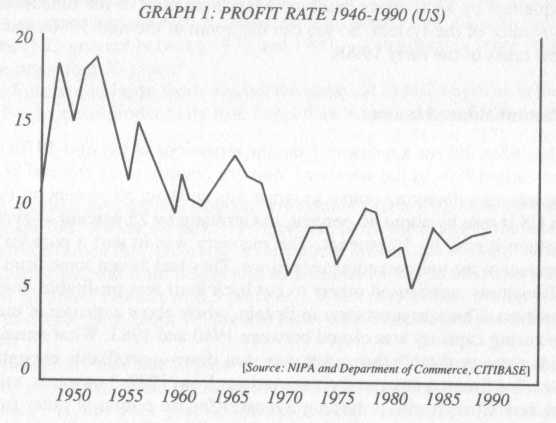

The analysis was vindicated by developments in the late 1960s and early 1970s. US big business found it could not sustain the burden of paying for the Vietnam War, although even at its peak expenditure on that war was substantially less than on the Korean War 15 years before, causing successive US governments to reduce the share of national output going to the military right through from 1969 to 1979. In the same years there was a fall in profit rates in all the major Western economies, leading the world into two recessions much more severe than any since the 1930s. [12]

|

|

But it is not only the world crises of 1974–6 and 1980–1 that can be explained by an analysis based on Marx’s account of the fundamental dynamics of the system. So too can the boom of the mid-1980s and the new crisis of the early 1990s.

The 1980s did see a recovery from the recessions of the mid-1970s and the early 1980s in the advanced Western countries. By the end of the decade manufacturing output in Japan was up about 50 percent on 1980, in US it rose by about 40 percent, in Germany by 25 percent – even in Britain it rose by 10 percent. The recovery was in part a paradoxical product of the two preceding recessions. They had driven some firms out of business and caused others to cut back their less profitable lines of business. This was most clear in Britain, where about a quarter of manufacturing capacity was closed between 1980 and 1983. What remained was more profitable than what was shut down – profitable enough, in fact, for firms to enlarge their operations from 1982–3 onwards, taking on new workers and providing a market for the output of other firms. The capitalist crisis was itself easing the tendency for investment to grow faster than the workforce and for the rate of profit to fall.

The recessions offset pressure on profit rates in another way as well. As firms produced less they used up smaller quantities of raw materials, causing the prices of these to fall and so cutting industrial costs. Thus one estimate for the US points to a fall in the relative price of means and materials of production by about 15 percent. [13]

Finally, the recessions reduced the resistance of workers and their unions to management cost cutting programmes. The most vivid examples were in the United States, where the threat of the closure of the third largest auto manufacturer, Chrysler, in 1980 led the UAW union to agree ’concessions’ which cut wages and health benefits. It was an example other firms and unions followed, until ‘concessions’ or ‘givebacks’ became the pattern for almost all collective agreements. At the same time, firms ensured that new plant was built in regions where union organisation was weak – either relying on anti-union ‘right to work’ laws to refuse recognition to unions or blackmailing unions into conceding low wages and workloads in return for recognition.

The overall result was a substantial cut in workers’ real wages. The real weekly income of a worker in 1990 was 19.1 percent below the level reached in 1973. The incomes of working class families did not usually shrink as much as this because of the growing tendency for wives as well as husbands to work. Nevertheless, average real incomes declined for all but the top fifth of families. [14] Since productivity continued to rise, the result was an increase share of output going to profits compared with that going to wages – an increase in the rate of exploitation. One calculation suggests that the rate of exploitation in ‘productive’ industry rose by about 25 percent between 1977 and 1987 – considerably more than in the preceding 30 years. [15]

In Europe and Japan there was not the same cut in real wages as in the US. But here too productivity rose faster than wages, and profits grew as the rate of exploitation increased. For the Group of Seven (G7) major industrial economies, the OECD estimates that the ‘share of capital income’ grew from 31.9 percent in 1975–9 to 33.9 percent in 1990. [16]

In Britain, average real disposable income from employment rose in the years 1987–89, by a total of 11.7 percent. But a shrinkage in the total workforce turned this into a rise of only about 0.2 percent a year in total disposable income from wages and salaries, and a fall in their share of Gross National Product of 6.3 percent. [17] In the mid-1980s ‘profits per unit of output grew about 1.5 percent faster than labour costs per unit of output’. [18]

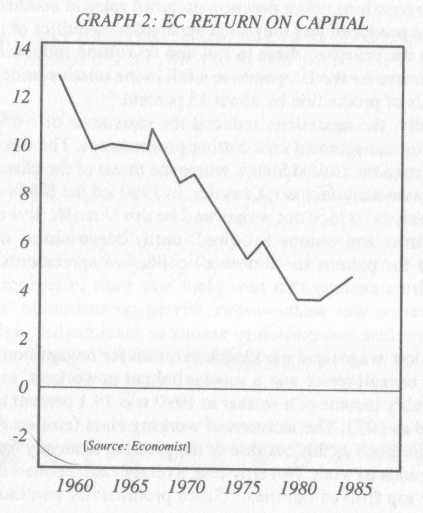

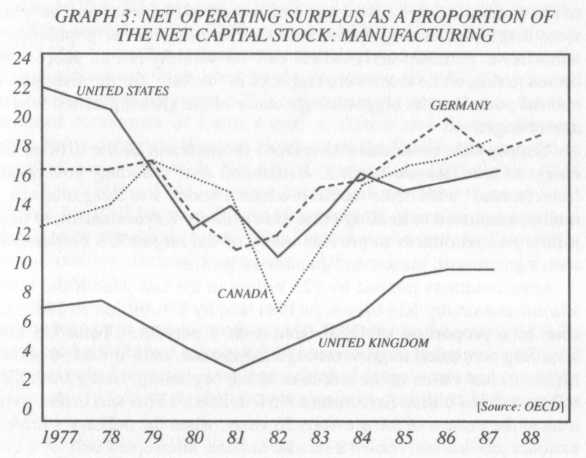

Profitability was able to grow in the 1980s with the slow down in the rate of accumulation and the increase in the rate of exploitation, as Graph 3 shows. [19] By the peak year of 1987 profitability in Europe (including Britain) and the US was reported as the same as in the early 1970s – although it was still lower than a decade before that. [20] In Japan the level was up from that of the late 1970s and early 1980s, but still way below that of the early 1970s and before. For the G7 major economies as a whole, profitability in 1990 was estimated at 15.3 percent – a slight rise on the 1975–9 average of 14.1 percent, but not a radical improvement. [21]

|

However, the economic recovery was not just, or even mainly, an automatic response to a partial restoration of profitability. It very much depended on government action, particularly in the US. The economic ideology of the Thatcher government that took office in Britain in 1979 and the Reagan government that took office in the US in 1981 was ‘monetarism’. Both claimed they would be able to prevent inflation by keeping a tight control on the money supply and government spending. Both embraced the wholesale dismantling of controls over various aspects of business behaviour – abandoning controls on the financial system and the money markets, deregulating industries like airlines in the US and buses in Britain, slashing into minimum wage provisions. Both pushed through cuts in welfare provision for the poor. Both slashed taxes on the rich and on capital.

But it soon became clear that Reagan’s policy and Thatcher’s diverged in one important respect. While Thatcher insisted she stood for a balanced budget, Reagan permitted a soaring federal budget deficit – $100 billion dollars in 1982 and rising inexorably through to 1986. Part of the deficit was due to falling tax revenues. Another part was due to the continuing upward pressure of those government benefits which went disproportionately to the better off sections of the population – subsidies to pensions and medical care for wealthy retired people continued to rise, while there were cutbacks in ‘welfare’ for the unemployed and the poor. But the biggest single cause of the growing deficit was the arms budget.

‘Supply side economics’ displaced monetarism as the official ideology of the Reagan regime. It claimed that reducing government ‘interference’ with firms would produce a boom. But Reaganomics, in reality, amounted to nothing other than military Keynesianism, to using military expenditures to provide many of the largest US corporations with a guaranteed market and guaranteed profits.

Arms contracts jumped by $25 billion in the last year of the Carter administration, by $24 billion in 1981 and by $44 billion in 1982, and rose as a proportion of GNP from 5 to 7 percent. [22] Total US arms spending continued to grow through the decade, until it was 50 percent higher in real terms at the end than at the beginning, rising from $206 billion to $314 billion (in constant 1990 dollars). [23] This was in sharp contrast to the pattern of the previous 30 years, when the military’s share of national product had shown a secular decline, interrupted only by a brief surge at the height of the Vietnam war between 1965 and 1969.

The military medicine produced a rapid turnabout from recession to growth. After contracting in 1980–1, the economy grew continuously from 1982 to 1989, the longest non-stop period of expansion since the 1940s. Unemployment (as officially measured) fell from around 10 percent to just under 6 percent, and the total number of jobs rose from around 100 million to just under 120 million. The American boom gave a boost to the economies of the other advanced countries and of the Pacific NICs as it sucked in imports, which grew by close on $100 billion in 1983 alone. Japanese industrial production, which had stagnated through 1980 to 1982, picked up in 1983 and soared in 1984–5; West German industrial production stormed ahead in 1984 and 1985 after staying below its 1980 peak right through to 1983; in Britain, France and Italy economic recovery began in 1982–3 and had taken off by 1984–5.

Yet there were weaknesses in the recovery. The driving force was the US. Yet the US economy suffered from two spectacular deficits – the budget deficit already mentioned, and a growing trade deficit. Whereas in 1980 US non-oil trade showed a surplus by 2 percent of GNP, by 1986 it was in deficit by nearly 3 percent. The US share of world exports fell by about a fifth, until it was below that of West Germany in 1987.

The deficits had to be financed. This meant borrowing – by the government from the banks, and by the US economy as a whole from the rest of the world. So US government debt grew from 19.1 percent of GDP in 1979 to 30.4 percent in 1989 [24] and total US borrowing from the rest of the world from $480,000 million in 1980 to $1,536,040 million in 1987. [25] One immediate effect was to force up real interest rates worldwide to a relatively high level by the beginning of 1983. They stayed high for the rest of the decade. This was especially damaging to the debt burdened economies of Latin America, Africa and Eastern Europe. While North America, Western Europe and the Pacific rim grew, they stagnated or even fell back. For Africa, ‘per capita GDP fell from $854 in 1978 to $565 in 1988, external debt rose from $48 billion to $423 billion ... By 1987 between 55 and 60 percent of Africa’s poor was considered to be absolutely poor.’ [26] For Latin America and the Caribbean, ‘the cumulative decline’ in regional GDP per head for 1981–90 was ‘about 10 percent’. [27]

At the same time, the growth of the US economy was not accompanied by any large rise in productivity. Whereas in the years 1950–73 labour productivity had grown at 2.5 percent a year, in the years 1973–87 it grew at only 1 percent – less than a third of Japan’s rate and two fifths of Germany’s (although absolute productivity remained higher in the US). [28]

The weaknesses in the boom were shown in the years 1985–6. There was a tailing off of growth in G7 major advanced countries, halving to 2.7 percent in the US and remaining stuck at around 2 percent in Germany and France. [29] G7 investment grew at only a third of 1984’s rate in 1986. [30] And industrial output actually fell in both Japan and the US in the spring of 1986. [31] No wonder many commentators argued the world was on the verge of a new recession [32], with the Economist reporting, ‘America’s economists are asking what lies ahead this year, continued growth or slump?’

Such predictions were grossly wrong. The tendencies towards recession were certainly there, but they were more than compensated for by two other factors. First, the arms build up in the US continued, despite the moves towards a disarmament deal between Reagan and the head of the USSR, Gorbachev, at the Reykjavik summit in the autumn of 1986. Second, the governments of the major Western powers all took measures to stimulate the economy. The US went furthest, cutting its interest rates, allowing the international value of the dollar to slide (so cheapening exports), slashing income and company taxes, increasing the budget deficit (despite its avowed commitment to cut it in line with the new Gramm-Rudman bill) and putting pressure on the Japanese and German governments to expand domestic demand. These governments did not fully comply, but made some gestures to appease US pressure. In Britain the Tory government relaxed its controls on public expenditure and cut taxes in the run up to an election, turning its back on its own avowed monetarism as ‘broad money’ (M3) grew by 20 percent.

Such action by governments produced a new spurt of growth in 1986–7 – 3.5 percent in the US, 5.3 percent in Japan, 2.5 percent in France, 4.6 percent in Britain, with Germany lagging at under 2 percent. [33] In both Japan and the US (although not in most European countries) industrial output grew much more rapidly than the economy as a whole. The new boom was a real boom, in the sense that it led to the production of a growing mass of tangible commodities. But the boom was much greater in the financial sector of the economy than in material production.

Financial activity became frenetic, with stock and share and property values soaring upwards. Vast amounts of borrowing sustained the growing number of corporate takeover bids and counter-bids. Small companies took over much larger ones through ‘leveraged buy-outs’, financed by borrowing against high interest ‘junk bonds’ which had to be paid for by selling off the assets of taken over companies. For a time the speculative boom fed on itself. Financiers outbid each other for property and shares, bringing about the very upward surge in markets they had predicted. The speculative profits they made were in turn poured back into the markets, forcing them still higher. The paper profits so created financed a great burst of luxury consumption – it was then that the term ‘yuppie’ really came into fashion on both sides of the Atlantic.

The Economist could note ‘the contrast between frenetic money and sluggish economies’ at the end of 1986:

Money always talks, of course, but in 1986 the noise was deafening. First the foreign exchanges screeched as the dollar fell another 11 percent. Then came Big Bang in the City of London, part of the world spanning trend of financial innovation and deregulation ... Somewhere in the background was the sound of centra! banks letting their money supplies rip through the roof ... By contrast, the ‘real economy’ was too quiet. [34]

The contrast between the explosive expansion of finance and the slow growth of material production made national authorities worry about inflationary pressures. The American federal reserve responded by trying to restrict credit and raise interest rates. Stockmarkets throughout the world plunged on ‘Black Monday’, October 1987, with shares losing about a third of their value in Europe and America (although being much less severely hit in Japan).

Once again there were widespread predictions of an imminent slump, with comparisons with the Wall Street Crash of 1929. [35] But once again the slump did not materialise because of governmental action. Governments everywhere did a U-turn, relaxed controls on the money supply, allowed interest rates to fall and poured billions of dollars into the financial system to prevent it collapsing. In this, they had the backing of many monetarist hardliners. Thus Samuel Brittan advised:

When a slump is threatening, we need helicopters dropping currency notes from the sky. This means easier bank lending policies and, if that is not enough, some mixture of lower taxes and higher government spending. [36]

The Economist, at the time a standard bearer of monetarism, was equally forthright: ‘The immediate task is a Keynesian one: to support demand at a time when the stock market crash threatens to shrink it.’ [37]

Governments forgot all about controlling the boom – and the speculative frenzy was soon at full throttle again. The American and European stock markets remained relatively subdued, but the junk bond crazes resumed with the biggest attempted leveraged buy out yet, that of RJR Nabisco. [38] Property speculation rose to new heights, and private borrowing reached record levels in the US, Britain, and Japan. By the end of the 1980s bank loans in the US had more than doubled [39] and in Japan they were three times their level at the beginning of the decade. In Britain borrowing by the personal sector soared from under 9 percent of disposable income in 1984 to 16 percent in 1988 [40], while the ‘gearing’ ratio of company debt to capital stock doubled between 1987 and 1989. [41]

This was the period of what the Japanese later called the ‘bubble economy’, in which Japanese property values soared and the stock exchange doubled in value – until the net worth of Japanese companies was said to be greater than that of the US companies, although by any real measure the US economy was about twice the size the Japanese one. In Britain these years saw the office building boom in the City of London and docklands, the construction of new shopping malls in every town of any size, the proliferation of out of town hypermarkets, and the finance and real estate sector growing until it accounted for nearly one job in eight (as against one in 14 in 1979) and a fifth of total value added. [42]

|

There was real industrial growth, but it was dwarfed by the expansion of the property markets and by various forms of speculative activity.

‘General business’ investment grew considerably faster than manufacturing investment – in sharp contrast to the 1960s and early 1970s, when manufacturing grew at the same speed. What is more, the growth of manufacturing investment was about a third lower in the US and Japan, and about two thirds lower in Europe, than in the earlier period.

|

Average Annual Percentage Growth Capital Stock: |

||||

|

|

1960–73 |

1979–89 |

1983 |

1989 |

|

US |

3.7 (4.0) |

3.5 (2.3) |

2.8 (1.3) |

3.5 (2.1) |

|

Europe |

5.2 (5.1) |

2.9 (1.3) |

2.6 (0.8) |

3.4 (2.0) |

|

Japan |

12.4 (12.4) |

7.3 (5.4) |

6.5 (5.4) |

9.4 (7.6) |

In Britain, while total investment in the economy rose from about 14 percent of GNP in 1984 to 18 percent in 1989, manufacturing investment rose from only about 3 percent to 4 percent [44] – the increase in industrial output of about 15 percent compared with 1982 was mainly due to greater use of existing plant and machinery, with capacity utilisation rising to close to 100 percent. [45]

At the height of the boom some establishment economists claimed the discrepancy between general business growth and manufacturing growth did not matter, since, they argued, in a modem economy services increasingly replace manufacturing. Now, it is certainly the case that some ‘services’ are every bit as much tradeable goods as are manufactured products. They are commodities which are sold for a profit, and the labour that goes into them is productive [46] – the worker who writes software is no less productive than the one who makes the computers it runs on. But by no means all ‘services’ are productive in this sense. Very many are simply concerned with protecting the already created wealth of the ruling class (for instance the security industry and the police) or with dividing and redividing that wealth within the ruling class (the financial sector, the sales and advertising industries, most civil law). A growth of such services is a drain on the productive economy, not a boost to it. And there are many indications that it was such services that experienced the greatest growth in the 1980s, while the pattern for genuinely productive services was very similar to that for manufacturing.

A study of the US shows that although some growth of services in the early and mid-1980s was a sign of ‘positive developments’ – for instance, new jobs as programmers, systems integrators, designers and bioengineers – ‘the overwhelming preponderance of service jobs created in the last 15, ten or even five years ... are very traditional: wholesale and retail sales, routine office work, janitorial work, security and so on.’ [47]

In Britain investment was not just concentrated in the service sector, but above all in the non-productive service sector. It rose by two thirds in distribution and more than trebled in finance. [48] The ‘investment boom ... was mainly concentrated in the non-traded sector of the economy: financial services, estate agents, shopping malls etc. ...’ [49]

The boom was an unbalanced, flawed boom. It concealed the real weakness in capital accumulation for a number of years. But eventually that weakness would destroy the boom and throw the whole world economy back into overt crisis.

In 1987 and 1988, with elections in Britain, France and the US, it was convenient for governments to play up the successes of the economy – most famously in the case of the British Chancellor of the Exchequer, Nigel Lawson, who spoke of a ‘British economic miracle’ when ‘carried away’ in the course of an after dinner speech, as he now explains. But by 1989 some of the imbalances in the boom could no longer be ignored. Everywhere inflation began to rise. [50] In the US the leveraged buy out and junk bond mania increasingly worried top businessmen, who feared the risk to themselves from speculative predators and the cost to major corporations of exorbitant interest payments on junk bonds. ‘The debt binge. Have takeovers gone too far?’ asked the Business Week cover in November 1988. [51] The worries grew with the sudden crash of the whole Savings and Loans sector (the equivalent of building societies) as a result of unregulated speculation, with the government having to pledge hundreds of billions of dollars to keep it afloat. Finally there was continuing anxiety about the budget deficit.

In Britain the imbalances caused an even bigger headache for the government. The lack of productive investment meant the boom was very much a boom in imported goods. The balance of payments moved from a narrow surplus in 1985 to a £20 billion deficit in 1989, while inflation levels reached 8 percent and more. The Economist, ecstatic about the Thatcherite programme only two years before, now noted that:

real domestic demand was growing by an astounding 9.4 percent in the second half of 1987, business investments at more than 18 percent in real terms ... The question future economic historians will struggle to answer is how Mr Lawson could have allowed demand to grow at least three times as fast as potential output. [52]

But most establishment economists continued to hold that the imbalances were not that serious. All that was required was limited government action to prevent the boom getting out of hand and growth would continue its healthy upward path without inflationary consequences. Typically, the International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook could argue in the autumn of 1989:

Some slowdown from the rapid growth rates of recent years appears to be taking place in North America and the United Kingdom ... At present there is no clear evidence from balance sheets and profit margins to suggest that sectoral imbalances have built up to an extent that might give rise to an abrupt adjustment by consumers or enterprises ... The current level of corporate leverage is still low by international standards. Similarly, the relatively rapid rise in household gross debt in several countries has been matched to a large extent by the rising value of household assets. [53]

Such arguments led the official orthodoxy to insist that limited measures, mainly pushing up interest rates, would bring about a ‘soft landing’ and sustainable non-inflationary growth.

This optimism was repeated again and again over the subsequent three years. The IMF and the OECD repeatedly predicted growth when there was to be stagnation or even shrinkage. Thus the OECD asserted in June 1990 that ‘economic activity in the industrialised world has settled to a sustainable 3 percent annual growth rate’, with prophesies of growth in 1991 of 2.5 percent for the US and 1.9 percent for Britain. Strong exports, it said, would save the UK economy from recession. [54] In fact, the following year saw a fall in output of 0.6 percent in the US and 3.7 percent in Britain. [55] In that year:

The IMF’s distinguished team of forecasters largely failed to forecast the Anglo-Saxon move into recession. In this failure it was largely representative of model based forecasters ... The consensus of UK independent forecasters was that the UK economy would grow by 1.8 percent, not decline by as much. [56]

The orthodox wisdom was, in fact, doubly wrong. More government action than it predicted was needed to bring the boom under control. And that action did precipitate recession.

In the US the federal reserve bank raised interest rates in stages by 3.5 percent, or by more than half, in the year up to April 1989. [57] The British chancellor, Lawson, had doubled them by the time he resigned in the autumn of that year. Yet the boom continued and inflationary pressures grew still greater. On both sides of the Atlantic the very deregulation that had helped drive the speculative boom forward made it more difficult to bring it under control.

But that was only a prelude to what happened in 1990. The expected ‘soft’ landing turned out to be very hard indeed. Both Britain and the US entered into real recession, not just the ‘growth recession’ that political and economic leaders had been expecting. And the recession proved more difficult to get out of than any since the Second World War. How did the orthodoxy manage to get it so wrong?

The establishment optimism of 1988–9 assumed that the boom was a response of business to a genuine and sustainable growth in profits throughout the system. So the IMF saw profits as being easily able to pay for increased bank lending in the US, and the increase in total outstanding loans as easily being compensated for by the increased value of assets. [58] Similarly, in Britain the Economist magazine argued in the autumn of 1989 that, while rising interest rates would hit small and medium sized companies, the relatively high level of big companies’ profits would protect them. [59]

The figures seemed to bear out these claims. They showed profit rates as more or less maintaining the level they had risen to after the recession of the early 1980s [60] So they were estimated to be 14 percent in the US in 1989 [61] and to have reached 19.5 percent for the largest British manufacturing companies in 1989. [62] Even when the recession was well under way, the Bank of England could claim profit rates ‘at the end of 1990 were close to the average for the last 20 years’. [63] But this raises an important question for any analysis of the economy. If profit rates were as healthy as claimed, why the sudden development of recession?

Part of the answer is that the figures showed profits as recovering to the levels preceding the major recession of 1974–6, rather than to the higher levels that sustained the long boom of the 1950s and 1960s. But there is also considerable evidence that real profitability of industry in 1987–8 was lower than the figures suggest.

Toporowski has pointed out that the British figures do not give an accurate picture of conditions for domestically based competitive production. [64] They include the foreign earnings of British multinationals and the high monopoly profits of recently privatised utilities. He quotes the government publication Economic Trends 1989 as saying company profits had been ‘consistently overstated’, and then, using his own economic model, suggests that ‘the share of profits in the national income was still, in the first half of 1988, below the share at the end of the 1970s’.

More generally, the merger boom of these years gave an enormous incentive to firms to use creative accounting to overstate their profit levels. This raised their share price, making it cheaper for them buy other firms if they were predators, and easier to ward off hostile takeover bids if they were not – and, in any case, could provide nice windfall profits for directors who chose to sell off their own shares. A recent book on the Murdoch empire points out:

The majority of people who see ... accounts assume they provide an unchallengeable and factual account of what is going on. Columns of neatly laid out

figures of a company’s profits have a tempting certainty to their appearance. But as Susan Dev, professor of accounting at the London School of Economics, once said, ‘Profits are not facts; they are just opinions’.

This is one of the great truths of accounting – privately admitted but frequently denied in public by accountants ... When a company draws up its accounts it needs to make a lot of assumptions. This is mainly because at the end of the year there is a lot of unfinished business, which creates uncertainties. For example, there are unpaid debts, and a judgement has to be made about whether these will be paid. There are lots of assets and a judgement has to be made about how long these will last. All these are subjective judgments: one company may decide that all the debts will be paid; another that none will be. The second company will then write off the debt and declare less profit that year. Profit then is a matter of opinion. [65]

Accountants are meant to abide by accounting standards which attempt to impose some uniformity on the basis for arriving at such opinions. But the standards vary from country to country, and in any case do not necessarily keep up with the new practices firms use in determining their own profit levels. For example, Rupert Murdoch’s News International declared after-tax profits for 1989 of A$1,163,626,000, which were nearly three times those of 1987. But this was using Australian accounting standards. If US standards had been used, the profit level in 1989 would only have been about 3 percent up on 1987. [66]

British accounting standards are said to be more stringent than Australian ones. [67] But in the summer of 1992 the head of research for London stockbrokers UBS Phillips and Drew, Terry Smith, caused a scandal (and lost his job) by publishing a book which listed a number of ways in which British companies could rig their profit figures quite legally and provided a list of very large companies that had done so in the late 1980s. [68] The ability of British based firms to exaggerate their profits was reduced when a new accounting code, FRS3, was introduced in 1992: profits for the giant construction, engineering and shipping conglomerate Trafalgar House, which would have been about £122 million under the old standard, turned into a loss of £38.5 million. [69] Marx noted in Capital:

The semblance of a very solvent business with smooth rate of returns can easily persist even long after the returns actually come in at the expense partly of swindled money lenders and partly at the expense of swindled producers. Thus business always appears almost excessively sound right on the eve of a crash ... Business is always thoroughly sound until suddenly the debacle takes place. [70]

The late 1980s provides innumerable instances of such inflated profits, giving a completely distorted picture of the health both of individuals firms and of the capitalist system as whole. The picture of lower than reported real profits is confirmed by a different set of figures: those for interest rates, which remained high throughout the mid and late 1980s.

There is usually an inverse relation between the rate of interest and the rate of profit, one rising when the other falls. [71] This is because the level of interest rates depends on the inter-relation between the flow of funds into the financial system and the demand for borrowing from it (banks and governments can only manipulate interest rates within parameters which depend on this inter-relation). And most inflow of funds comes from profits generated by industry and lent to the banks. [72] When profits are high, the flow of funds into the financial system grows and the supply exceeds the demand. There is a fall in the cost of borrowing – the rate of interest. On the other hand, when profit rates are low, the flow of funds into the banking system tails off, demand exceeds supply, and the cost of borrowing is forced up. On top of this, low profit rates leave firms which want to invest with no choice but to increase their borrowing, so increasing the demand for funds just as the supply falls and driving interest rates still higher. [73]

The high interest rates of the mid-1980s to late 1980s are thus an anomaly. They show that reported profit rates seriously overstate the real ratio of surplus value to investment throughout the system. This anomalous result was not just a result of the misreporting of firms’ profits. It was also a reflection of the changes in the system brought about by the concentration and centralisation of capital.

The recession of the early 1980s had not, in the main, resulted in a large number of outright bankruptcies. Rather, when firms were on the brink of collapse political pressure was applied by banks or governments (or both) to keep them afloat, most famously in the case of Chrysler in the US. But this meant their losses were transmuted into debts to the banking system either directly, by the banks lending them more, or indirectly, by governments bailing them out and then increasing their own borrowing from the banking system. In either case, losses disappeared from the balance sheets of firms to reappear as lending on the balance sheets of banks.

At the same time, governments everywhere did their best to reduce the pressures on the post-tax profitability of companies by cutting business taxes. In the US profit taxes fell from a third of total taxation in 1950 to a sixth in the early 1970s and little more than a tenth in the late 1980s. This contributed to the budget deficit, and so, again, added to the burden of total borrowing on the system as a whole. [74] In the mid-1980s it was not just individual firms that had to be bailed out by the rest of the system. Major states like Mexico, Brazil and Poland came close to bankruptcy and had to be propped up by co-ordinated action between the world’s biggest banks and inter-governmental agencies like the IMF.

As the speculative boom began to come unstuck in the late 1980s, states were once again forced to reach into their own coffers to protect giant firms. Thus the US government poured funds in to cover the losses of the Saving and Loans – and had itself to get those funds by an increased level of borrowing. In this case, upward pressures on the general rate of interest were a direct product of the creative – and often fraudulent – accounting that had made the Savings and Loans seem so profitable. In other cases, the greed of the banks had led them to lend massive amounts to companies who then used those funds, in one way or another, to bolster their declared profits. Robert Maxwell, head of the world’s biggest printing and publishing empire, made fraudulent gains in this way before he drowned himself and his empire sank, and so did the giant Bank of Credit and Commerce International.

The fraud is not the important point, however. What is significant is that the measures that seemed to raise the profitability of the corporate sector of the economy also increased the overall burden of debt and interest on the productive sector of the system, weakening its ability to undertake sustained accumulation. This is shown by the trend of investment. It did not, in most cases, flow into the productive sector as it should have done if profit rates had really been as high as they seemed. As Glyn has noted, ‘In the UK, between 1979 and 1989 investment in industry and agriculture stagnated, that in distribution doubled and that in finance more than trebled. The data suggests a similar, and possibly more exaggerated pattern in the USA.’ [75]

In fact, only at the very end of the boom, in 1988–89, was there a rise in most countries in either general business or manufacturing investment. [76]

Another element has to be taken into account besides the level of profits in any turn from boom to slump. This is the level and nature of consumption. There are theories which provide a simple account of recessions in terms of the low level of consumption. Such ‘underconsumptionist theories’ were developed by early political economists like Malthus and Sismondi and taken up by later liberal economists like Hobson and Keynes. Marxist versions of them have also been developed, most notably by Rosa Luxemburg and more recently by Paul Sweezy and Paul Baran. [77] The basic form of the argument is that in a profit based economy there is, by definition, always a gap between what workers produce and what they consume. The bigger this gap is – that is, the greater the profitability of the system – the greater is the likelihood that there will not be enough consumer demand to buy everything the workers produce.

These theories are wrong because the gap between output and demand will be filled if employers use their profits to invest in new plant and equipment – and they will if profitability is high enough. [78] Nevertheless, the theories do focus on an aspect of the instability of capitalism – as Marx recognised when he noted that, ‘the ultimate reason for all real crises always remains the poverty and restricted consumption of the masses as opposed to the drive of capitalist production to develop the forces of production as though only the absolute consuming power of society constituted their limit.’ [79]

As we have seen, the accumulation of capital involves the means of production growing much faster than the number of workers. The amount of profit can only keep pace with the rise in the total level of investment if more profit is produced per worker – that is, if the share of output going to workers falls as the total output rises. Otherwise there will be a fall in the rate of profit. Therefore, success for the system depends on a continual widening of the gap between total production and working class consumption. But the wider this gap is, the more the stability of the system depends upon investment – which in turn depends upon maintaining the rate of profit by a further widening of the gap.

If anything happens which damages the rate of profit, then investment will suddenly not be sufficient to bridge the gap between output and consumption. Firms will not be able to sell all the goods they produce. They will be forced to hold their prices down. Profits will fall further, investment will be further cut back, more goods will be unsellable, and a general crisis of overproduction will result.

The dynamic of the system itself, the drive to accumulate, has created conditions in which the consumption of the masses is too high to permit the rate of profit required for further accumulation, but too low to absorb the output of industry. Raising the consumption of the masses cannot solve the crisis, because it means further cuts in overall profitability and a further threat to accumulation. Lowering the consumption of the masses cannot bring about an immediate solution to the crisis either, since it lowers the demand for output and prevents firms immediately restoring their profits.

These are precisely the conditions we see operating through the 1980s. The rate of profit was partially restored by reducing the workers’ share (in Marxist terms, by increasing the rate of exploitation). But the restoration was not enough to bring investment to its 1950s–1960s level. Total output continued to be greater than investment and workers’ consumption combined. Overproduction was an ever present possibility.

However, if this can explain why the system was prone to crisis, it cannot explain why the crisis did not break sooner, say with the little dip of 1985–6 or with the stock exchange crash of 1987. The boom rather than the slump becomes a problem for the analysis.

To come to terms with this problem, something else has to be looked at as well as productive investment and workers’ consumption: the range of non-productive expenditures by the capitalist class. The luxury consumption of the capitalists themselves falls into this category. It absorbs the products of the system without creating any fresh ones. So does the consumption of those who provide a range of services for the capitalists – their servants, their lawyers and private doctors, their security guards and, through the state, their military and police establishments.

On top of this, there is also expenditure by capitalists (both individual and corporate) on trying to increase their share of markets and profits at the expense of other capitalists – for instance, through advertising and sales promotion, speculation in property development and on the stock market, the borrowing and lending of money. These ‘non-productive’ expenditures always exist. But many of them tend to be overshadowed by productive expenditures when the system is booming. At such times capitalists find it easy to make and realise profits on whatever their plants produce. They are not driven to enormous non-productive expenditures in order to survive.

But the picture changes when the boom begins to falter. Increased advertising and sales expenditures become essential to any capitalist who wants to beat competitors. The lure of speculative profits is all the greater when profits from direct production are under threat. And psychological factors can push up the luxury consumption of the capitalist class. Conspicuous consumption becomes the norm in an ‘eat, drink and be merry for tomorrow we die’ atmosphere. The same crisis which reduces the level of productive investment can increase non-productive expenditures, and these can provide a boost to the flagging demand for the output of industry.

Grossman noted the relation between the crisis in productive industry and the growth of speculation shortly before the Wall Street Crash in the 1920s:

... Over-accumulated capital faces a shortage of investment possibilities ... The superfluous and idle capital can ward off the complete collapse of profitability only through the export of capital or through employment on the stock exchange ... Thus in the depression of 1925–6 money poured into the stock exchange ... The fever of speculation is only a measure of the shortage of productive investment outlets ... [80]

Writing after the crash and the slump which followed it, Lewis Corey stressed how such unproductive expenditure had succeeded in prolonging the boom during the ‘Roaring Twenties’, only to make the eventual crash even more severe. [81]

Such unproductive expenditure played a similar role in the 1980s. The decade saw a burgeoning of military, advertising, sales, speculative and luxury expenditures, which reached their peak in 1987–9. Particularly after the incipient economic downturn of 1985–6, funds poured into property, business services and the stock exchange, looking for profits which could not be obtained through productive investment. At the same time, the British and American governments gave a huge boost to the incomes of the very rich and a smaller boost to the spending of the middle classes through tax cuts, encouragement to firms to pay larger top salaries, deregulation of finance and ‘give away’ privatisation share prices. ‘In 1980s the chief executive officers of the three hundred largest American companies had incomes 29 times higher than that of the average manufacturing worker. Ten years later the incomes of the top executives were 93 times greater.’ [82] In Britain the rate of growth of company directors’ incomes was 20 percent a year throughout the 1980s [83]; dividend payments of the largest 1,400 companies rose 20.4 percent in 1988, 33.9 percent in 1989 and 20.3 percent in 1990; [84] real manufacturing dividends were 73 percent higher in 1989 than ten years earlier, while ‘the total real wage bill was nearly 5 percent lower’. [85]

Unproductive expenditure by companies and huge handouts to the rich did provide markets for productive firms like those making luxury cars or supplying the construction industry. They also created jobs for non-productive employees – market makers, lawyers, estate agents, bank employees, advertising executives, and so on – who in turn increased demand for other industries. Huge amounts of wealth were created in these years, despite the slow tempo of accumulation. But it was a form of wealth creation that could only be self-sustaining up to a point. It was parasitic off the profits generated in productive industry, recycling them in a frenzy of greed and gluttony. And if these profits started to dip seriously, the whole edifice of business speculation and luxury production would come tumbling down.

Accumulation in productive industry was slow. But some did take place, causing investment per worker slowly to rise. The ratio of means and materials of production to the workforce in US productive industry [86] grew by 2.37 percent a year in 1977–87 – a substantial amount, even if less than the 3.47 percent a year in the previous decade [87]; in Britain ‘the working population tends to be static, while the stock of capital grows ... The capital stock was rising at 4 percent a year in 1970, decelerating to 2 percent a year’ in the mid-1980s. [88]

In the early 1980s the rise in the rate of exploitation had been sufficient to compensate for this growth in the ratio of investment to workers. But in the late 1980s this was less and less so. The growth in manufacturing productivity remained below the level for the years 1983–4 [89] – for ‘all industrial countries’ output per man hour grew 5.1 percent in 1983 and 5.4 percent in 1984, but only 3.3 percent in 1987, 4.6 percent in 1988 and 3.6 percent in 1989. What is more, by 1988–9 employers everywhere were finding it difficult to hold back wages as unemployment fell from its previous heights. Statistics show general wage rates and unit labour costs accelerating in most industrial countries in 1987–8 – especially in the US and Britain. [90]

Yet the total investment to be financed out of profits continued to grow. Even after the stock exchange crash of October 1987 the frenzy of investment for non-productive consumption continued. In Britain, for instance, construction of London’s biggest office project, Canary Wharf, did not actually start until November 1987, while the assets of one of Britain’s biggest property developers, Rosehaugh, rose sharply in both 1988 and 1989. [91] And Britain was by no means unique: similar phenomena could be witnessed right across the world, with office blocks continuing to spring up in Tokyo, Toronto, New York and even Lahore. What is more, the rise in general business investment was accompanied in the last couple of years of the boom by an upward surge in manufacturing investment in most of the major industrial countries.

Eventually a point was bound to come when businesses discovered the total mass of profits was no longer high enough to maintain profitability on their expanding investments. In the US this turning point came late in 1989. ‘Profits are in for a rough ride. Earnings unexpectedly sank 22 percent in the third quarter’, reported Business Week for the US economy late in 1989. [92] It blamed ‘rising wages’, with ‘unit labour costs up 5.5 percent ... double the average increases for the last five years’ and increased interest payments as a result of the merger boom.

In Britain, ‘predictions’ at the beginning of 1990 that profits ‘would march ahead at 10 percent or so’ were replaced in September by the realisation that they would fall. [93] In fact, the pre-tax profits of non-North Sea oil companies fell from just over 10 percent in mid-1988 to just over 6 percent in mid-1990. [94]

The fall in profits fed a vicious circle. It forced firms to borrow more to finance half finished investments. But it also reduced the flow of the funds into the banking system. Interest rates continued to rise, further cutting into profits and forcing firms to borrow even more: between 1987 and 1991 average bank borrowing by British firms more than doubled. [95] Inevitably some firms found they did not have the cash to pay their bills and went bust. Banks could not get the money they had lent back and their balance sheets suffered. Desperate to avoid further losses, they cut back on their lending to other firms. By March 1990 there was already talk in the US of a ‘credit crunch’ which could ‘pose an unanticipated threat to a weak American economy and push the US into recession’. [96]

In fact by late 1990 the recession was well under way in the US and Britain – although the British government still claimed it would be a ‘growth recession’. By the turn of the year there was no hiding the reality. In Britain a series of newspaper headlines hammered home the hard truth. ‘Concern grows in the City and on the High Street that the slump may just be beginning and worse is to come’, said the Observer. [97] ‘Investment fall points to deeper recession’, warned the Financial Times [98], and later, ‘Hard year for all, painful for many’. [99]

At first the companies which were worst hit by the recession were those most associated with the 1980s boom in non-productive expenditures, particularly property companies. The moment the boom began to slow it became clear that the speculative frenzy had sent the property market to completely unrealistic heights. The Economist could warn in October 1989 that there was already 10 percent over-capacity in office space in the City of London, with some 35 million square feet due to come on the market between 1990 and 1992, and that ‘with loans outstanding of nearly £27 billion to developers, bankers are beginning to sweat.’ [100] Yet it could add that, ‘in spite of the gloom, talk of a crash on the scale of the one in 1973–4 is pooh-poohed’. Three years later major property firms like Olympia and York (builder of Canary Wharf), Rosehaugh (co-builder of the Broadgate development and prospective builder of the Kings Cross development) and Heron had all gone bust, while a big question mark hung over other companies like Stanhope.

In the US the slump in the property market deepened the crisis of those who had lent to it – especially the Savings and Loans and the banks in regions like New England. In Britain the major domestic banks may not have gone bust, but the collapse cost them many hundreds of millions.

The problems of the property market and the banks hit firms in the productive sector of the economy – just as their own investments were paying diminishing returns. Some were tied into the property markets and banking themselves. Many turned to the banks to ease their cash flow problems just as the banks cut back on credit. All lost markets as the crisis of those who catered for the non-productive sector cut the general demand for goods. In Britain a host of firms that had risen to prominence in the Thatcher era went crashing down – Colorol, British and Commonwealth, Polly Peck, Maxwell Communications Corporation, Dan Air. Others survived by the skin of their teeth: Rupert Murdoch’s News International, for instance, whose sheer size was enough to scare an international coterie of banks from calling in their loans. In the US giants like Ford squealed, General Motors and IBM made the biggest losses ever known to manufacturing companies, and Pan Am went bust.

Once the recession was well under way those who had never predicted it hastened to put the blame on the governmental policies of two or three years earlier. If only governments had not put money into the financial system after the stock exchange crash of October 1987, they claimed, the property and lending boom would not have got out of hand and there would have been a soft landing in 1988 or 1989. More sophisticated analyses pointed the finger at the wave of financial deregulation in the early and mid-1980s. It was not that government deliberately allowed credit or the money supply to get out of hand. Rather, they had abandoned the mechanisms which once allowed them to control these things even as they espoused monetarist doctrine which gave a central place to such control.

But these arguments forgot – and still forget – two things. Firstly, the boom in speculation, non-productive services and luxury output throughout the 1980s, and the credit to finance it, was the only way the system could compensate for the failure of investment in the productive sector of the economy. Without the credit explosion apologists for the system would not have been able to claim in 1986 and 1988 that it had emerged gloriously from crisis. The period of economic recovery would probably have ended when it was barely three years old, at the time of the industrial downturn of 1984–5. Certainly, recovery would not have continued after the stock exchange crash of 1987.

In other words, the very factor that adds to the crippling overhang on the system now was responsible for the prolongation of the boom so extolled only four or five years ago. Without it the ‘new right’ would long ago have lost intellectual credibility and millions of words about ‘post-Fordism’, ‘post-Marxism’ and ‘postmodernism’ could hardly have been written. The fault was not with individual acts of government policy, but with a system which could not deliver the profit rates it needed to sustain itself.

Secondly, deregulation was a reflection of a more far reaching change taking place in the system – the internationalisation of production and finance as well as trade. For a long period, from the early 1930s through the early 1970s, governments had been able to exert a degree of control over the financial system because production was still very much nationally based. But the picture began to change as firms began to co-ordinate research, innovation and production across national frontiers and to scour the world for the means to finance fresh investment. With the crisis of 1974–6 many national governments discovered the hard way that national state intervention was no longer effective. Others tried to delay the reckoning in these years by borrowing internationally to keep their economies expanding, only to come down with an enormous bump with the crisis of the early 1980s. By the late 1980s even the most state regulated economies – those of China, the former USSR and Eastern Europe – were opting to replace controls over the flow of capital by enticements to capital to flow in their direction. And part of the enticement was to promise to regulate the behaviour of individual capitalists as little as possible. [101]

Deregulation and globalisation were a reflection of trends taking place inside capitalism which contradicted the continued dependence of the individual units of the system, capitals, upon nationally based states to protect their interests and police their interactions. The system required regulating if it was not to go completely haywire, but its development had made regulation much more difficult and contradictory than previously.

During the boom the new right economists claimed deregulation was behind new ‘economic miracles’ – as they still do with China and to a lesser extent India and a handful of Latin American countries. Since the collapse of the boom the remaining Keynesians have blamed deregulation for allowing it to get out of hand. What both fail to see is that changes within the very fabric of the system mean national states can no longer be effective in trying to stop either speculative booms or recessions getting out of hand. Monetarist and Keynesian methods are equally doomed by the system they attempt to keep running.

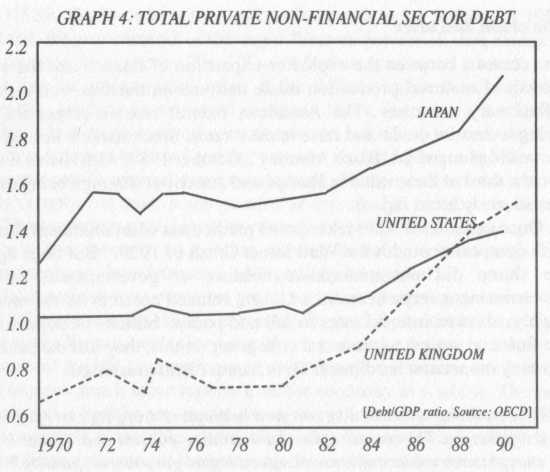

By late 1990 recession was already well under way in the US and Britain. But Japan and Germany were still booming, with growth rates of more than 4.5 percent. [102] The contrast between their continuing confident growth and the pessimism in the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ economies led to a lot of speculation by economic journalists about the superiority of their alleged ‘social market’ or ‘social capitalist’ economic models over the free market, ‘Thatcherite’ model preferred in the US and Britain. [103] But despite the delay in the onset of recession, the factors working towards crisis elsewhere were also present in these economies.

The West German economy was easily the biggest in Europe, producing nearly two fifths of European Community manufacturing output. This often led people to speak of it as a ‘superpower’ – especially after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 – and to assume it was doing much better than the other European states through the 1980s. But Germany by itself was not in the same league as the US economy, which was four times its size, or even the Japanese, twice its size. And its rate of growth over an 18 year period was actually a little slower than that of the US and the other continental EC states, and much slower than Japan’s. [104] Between 1979 and 1986 its share of world non-oil exports was lower than in the early 1970s [105] (while the Japanese share had grown about 50 percent), and its share of European Community manufacturing output was lower in 1985 than in 1970. [106] As William Keegan has noted:

The West German economy had not grown noticeably fast in the 1980s. Indeed, in international forums such as the OECD and the G7, the West Germans often came under assault from other countries for apparently being perfectly content with export led growth and for not going out of their way to stimulate the domestic economy. There were several years in which domestic demand hardly grew at all in West Germany. [107]

So Germany’s real manufacturing market only grew by 9.1 percent between 1970 and 1985, while those of France and Italy grew by 33.7 percent. [108] An excess of exports over imports meant a German balance of payments surplus approaching $50 billion by 1986. This kept the international value of the deutschmark high and, together with relatively low inflation, earnt the admiration of many establishment economic commentators in other countries.

But the slow growth rate also brought about a deepening sense of malaise throughout society. There was a small increase in the level of class struggle (for instance with the metal workers’ struggle for a shorter working week in the mid-1980s) and some talk in journalistic quarters of Germany catching ‘the British disease’ of increasing demands on a relatively stagnant economy. [109]

The German government did take action to boost growth after 1985, with a deficit on government spending of about 2 percent of GNP by 1988. This, combined with the renewed speculative boom in the US and elsewhere, led to a surge in German output, with a growth rate nearly twice that of two years earlier. But by mid-1989 the burst of growth was beginning to exhaust itself, prices were rising (although from a virtually nil inflation rate to 3 percent, which would have been regarded as low anywhere else), labour costs in manufacturing were up by over 4 percent, and the Bundesbank was seeking to ‘cool down’ the economy by doubling interest rates. But then came the collapse of the East German regime.

Chancellor Kohl pushed first for economic and monetary union and then for full political unification precisely because he saw it as a way out of the growing impasse of economic and political life in West Germany. In doing so he gave a new lease of life to economic expansion in west Germany. Its firms had no difficulty in taking markets from east German industries, driving the majority out of business. West German economic growth was even higher in 1990 and 1991 than it had been in 1988 and 1989. For the first time for two decades it was the locomotive of Western Europe. It pulled other economies behind it as its boom provided export markets for its neighbours, until in 1991 its large current account balance of payments surplus became a deficit.

But there was a very high price to be paid for this change. The goods which east Germans bought from west German firms had to be paid for – and the collapse of east German industry left the German government paying the bill. After balancing its budget in order to cool down the 1988–9 economic expansion, the German government was now spending much more than it got in tax income: its deficit was expected to reach 6.5 percent in 1992. [110] Authorities which had been worried by a 3 percent inflation rate in 1989 were faced with one of 4.8 percent in March 1992. [111] They reacted desperately: the Bundesbank forced up interest rates and the government imposed a special ‘unity tax’ aimed at cutting living standards in the west. Eventually the boom began, in mid-1992, to turn into a recession. Industrial output fell 3 percent compared with the year before and unemployment rose by a tenth. [112]

Commentators often blame Germany’s current economic problems on Kohl’s haste for unity in 1989–90. But this is to forget that an important reason for Kohl’s rush was that the first symptoms of crisis were already present then. After slow growth through the 1980s West Germany would have entered a phase of stagnation, if not recession, had Kohl acted otherwise. The German economics minister, Juergen Moellemann, admitted in December 1992 that ‘the economy was initially shielded from the downturn throughout Europe by the post-unification boom’. [113]

That boom, in fact, played very much the same role as the speculative booms of the late 1980s in the US and Britain – it postponed the moment of truth for a weakly based phase of economic recovery, only to make the eventual collapse into recession even more severe. And, as in the US and Britain, the root of the weakness lay in the fundamentals of the economy. The rate of profit had never fully recovered after the crises of the mid-1970s and early 1980s, rising slowly to just above the level of 1975–9. [114] This was sufficient to sustain a slow rate of accumulation through the 1980s; the moment faster accumulation was attempted, inflationary pressures and increased borrowing turned the boom into a slump.

Japan’s economy seemed able to resist the global pressures to recession in 1989 and 1990 even more than Germany. It had maintained a momentum of growth, continuing from 1976, with reduced growth rather than a real recession in 1980–1 and an average growth rate of 4.2 percent for 1980–9 (as against 2.7 percent for the US and 1.9 percent for Germany). [115] Then in 1989–90 its growth rate soared, touching an annual rate of 7 percent in the spring of 1990, as the US was going into recession. Even after a fall of the Nikkei stock exchange index by half early in 1990 established opinion was that the economy remained ‘buoyant’ [116] and the head of the Bank of Japan was more worried about inflation than recession. [117]

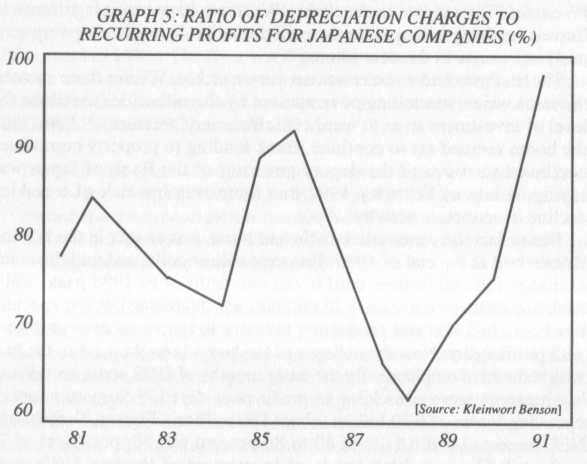

The growth, however, hid deep deficiencies. The rate of profit only recovered slowly through the 1980s (from a low of about 14 percent in 1982 to about 16 percent in 1988), so that at the end of the decade it was still considerably lower than in the 1960s and 1970s. [118] And even these relatively low profit rates required a very high rate of exploitation of the workforce. The average Japanese employee worked 200 hours a year more than his or her equivalent in Britain, while the proportion of GNP going to personal consumption, 54 percent, was said to be ‘the lowest level among OECD countries’ [119] The economy kept expanding because investment continued despite the low profit rate: ‘Business investment has been the real motor of the economy – accounting for more than 50 percent of economic growth since the end of 1986’. [120]