MIA > Archive > Harman

Chris Harman

Thinking it through

Divide and conquer

(May 1999)

From Socialist Review, No.230, May 1999.

Copyright © Socialist Review.

Copied with thanks from the Socialist Review Archive at http://www.lpi.org.uk.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Marxists’ Internet Archive.

Chris Harman on self determination and national liberation

‘The bourgeoisie of each country is ... asserting that it is out to defeat the enemy, not for plunder and the seizure of territory, but for the liberation of all other peoples except its own.’ Quotations from Lenin can appear like biblical texts, presented as sacred truths at the beginning of a holy sermon. But this one, written as the horror of the First World War was casting its bloody shadow across Europe, is relevant today, when Nato politicians tell us this is the first ‘humanitarian war’ and many who claim to be on the left concur.

‘The bourgeoisie of each country is ... asserting that it is out to defeat the enemy, not for plunder and the seizure of territory, but for the liberation of all other peoples except its own.’ Quotations from Lenin can appear like biblical texts, presented as sacred truths at the beginning of a holy sermon. But this one, written as the horror of the First World War was casting its bloody shadow across Europe, is relevant today, when Nato politicians tell us this is the first ‘humanitarian war’ and many who claim to be on the left concur.

Supposed concern for the horror being inflicted on small nations was central to the war propaganda of all the contending powers in the First World War. The catalyst for the war was Russia’s reaction to the invasion of a small Slav nation, Serbia, by a large Germanic empire, Austria: ‘Liberation of Serbia’ was the Tsarist slogan. France’s entry into the war was justified in terms of the opportunity to free the inhabitants of Alsace Lorraine from the ‘oppression’ they had suffered at German hands since the annexation of the region after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. The British pretext was the German occupation of ‘poor little Belgium’. German excuses for the war included the oppression of Poland at the hands of Russia – which led the most influential Polish nationalists to back Germany and to set up a puppet government on its behalf.

‘Humanitarian’ interventions did not end with the First World War. Hitler justified his intervention against Czechoslovakia in 1938 by talking, not of German imperialism’s drive for profits, but of the national oppression suffered by the German speaking minorities in the border regions of Bohemia and Moravia. Similarly, when the US stepped up their war in Vietnam in the mid-1960s, they claimed it was to protect those like the million Catholics who had chosen to move to the South when the country was divided in 1954.

What attitude should socialists have to calls for self determination in such circumstances? The starting point has to rest on two fundamental tenets. First, no group of oppressed people anywhere in the world can achieve their self emancipation unless they are able to decide on their own futures; the idea of one people forcing another to be free is a contradiction in terms. Second, the workers of one country cannot achieve their freedom if they continue to collaborate with their own rulers in oppressing the people of another country; as Marx put it, ‘A nation which oppresses another cannot itself be free.’

These general principles have, however, to be applied in concrete circumstances that are often complicated by other factors. The most important are the drive of imperial powers to grab control of as much of the earth as possible, and the coexistence within the same geographic areas of different national identities putting forward contradictory national demands.

Imperialist wars almost invariably involve great powers trying to use for their own ends national movements directed against their opponents. In some cases this amounts simply to providing a few weapons to movements which retain their own independence and follow their own goals – as with the attempts of the Kaiser’s Germany to help the Irish uprising in 1916 or the help the Vietnamese struggle received from Russia and China in the late 1960s. But in other cases, the once independent national movements have become mere playthings of imperialist powers. This was true, for instance, of the Slovak and Croatian governments established by Germany from 1939-45, or of the Polish government set up in German occupied Warsaw during the First World War. For socialists to support national movements that have acquiesced in such a role would be to help strengthen imperialism.

This was the issue Lenin and other revolutionaries had to confront. When the war began, he was quick to insist that Austria’s suppression of Serbian national rights in no way justified lining up with Russia’s ‘war of liberation’. ‘The national element in the Austro-Serbian war is an entirely secondary consideration and does not affect the general imperialist character of the war.’

The whole international socialist movement had traditionally identified with the demand of the Poles for national rights. But once the Polish nationalists aligned themselves with the Kaiser, Lenin insisted:

‘To favour a European war purely and simply in order to obtain the restoration of Poland would be nationalism of the worse sort. It would place the interests of a few Poles above the interests of the hundreds of millions of people who would suffer in such a war ... [for Polish revolutionary socialists] to put forward the slogan of Polish independence now, in the present relations which exist between Poland’s great imperialist neighbours, would be to chase after a will-of-the-wisp, to get lost in the pettiest form of nationalism.’

When Russian liberals began to demand freedom of Poland from German occupation, he reiterated,

‘Russian social democrats must expose the deception of the people by Tsarism, now that the slogans of “peace without annexations” and “independence for Poland” are being played up by Russia, for in the present situation both these slogans express and justify the desire to continue the war. We must say, No war over Poland.’

The other complication, the coexistence of different national groupings with contradictory demands, has long been a feature of the Balkans. Capitalism developed late there and led to middle classes from different linguistic groups (Serbian, Bulgarian and Macedonian Slavs, Romanians, Greeks, Albanians) each attempting to hegemonise the economic opportunities available in particular regions by drawing the peasants behind their own national banners. But each was too weak to do more than create a patchwork of territories which overlapped patchworks of territories influenced by their rivals. The fight for influence became the fight to expand rival patchworks into rival states, each with its own national mythology of a ‘heroic past’ going back many centuries, its own ‘glorious’ national monuments, national heroes – and its monopoly of well paid posts for those with the right national background. In each case, the other side of the establishment of the national state was the oppression of national minorities within it – Hungarians and Roma in Romania, Turks in Bulgaria. Serbs in Austrian run pre First World War Bosnia, Slovaks and Roma in post First World War Hungary, Muslims in Greece, Greeks in Albania. In each case, too, the only way one weak national state could maintain its control over the minorities within its boundaries, in the face of other weak states which allegedly stood for the rights of those minorities, was to form close alliances with the major imperialist powers. Hence the history of the Balkans has been the history of great power interventions.

The nationalist mythology of Balkan peoples has repeatedly found enthusiasts among the European intelligentsia: Byron died fighting for the Greeks; Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina ends with the hero going off to fight for the Serbs; fascists and left wingers alike enthused for Croatia in 1992. But the reality has always been very different from the mythology. Strengthening one ‘national’ Balkan state against its rivals has usually involved driving out, through the most barbaric means, groups which might identify with rival Balkan states. What is now called ‘ethnic cleansing’ was a feature on all sides in the two Balkan wars of 1912-13, of the Turkish-Greek war of the early 1920s (with 1 million refugees on either side), of the Second World War (when Ustashe Croats butchered Serbs, Serbian Chetniks wreaked vengeance on Croats, and some Kosovan Albanians joined the SS, while Tito’s partisans fought desperately to unite all ethnic groups against the German occupation). And, of course, it was a feature of the Yugoslav wars of the early 1990s, when not only did Serbs murder Muslims and Croats, but Croats waged a bloody murder campaign against Muslims in the Vitez and Mostar areas and ‘ethnically cleansed’ Krajina of its Serbian inhabitants, and Muslims slaughtered Serbs in the suburbs of Sarajevo. West European left wingers who started off by cheering on the ‘national struggle’ of Croats or Muslims ended up apologists for such actions, just as did those who cheered on the Serbian state. As Trotsky, who covered the horrors of the 1912-13 Balkan wars as a journalist, observed ‘for the benefit of nationalist romantics’, ‘Even in the backward Balkans ... there is room for national policy only in so far as this coincides with an imperialist policy.’

How do these considerations apply to the present situation in Serbia and Kosovo? The imperialist purpose behind Nato’s continuing war is clear. Even proponents of US imperialism like Kissinger who were hesitant about the need for war on 24 March are now convinced it has to be fought to the finish. They can see clearly the war has nothing to do with humanitarianism, but with the insistence by US imperialism that it can punish any state that defies it. The war is completely at one with US policy elsewhere in the world.

Not so clear to some people is what has been happening to the Kosovan Albanian national movement. This grew in the 1960s out of the resentment of the Albanian majority in the region that they were denied the full national rights available to Slovenes, Croats, Montenegrans, Macedonians and Serbs. The Albanians were as much second class citizens in Kosovo as the Catholics in Northern Ireland or the Kurds in Turkey although they had not always been the underdogs. The movement grew further when, after equal rights were briefly granted in the 1970s, these were taken away by Milosevic in 1989.

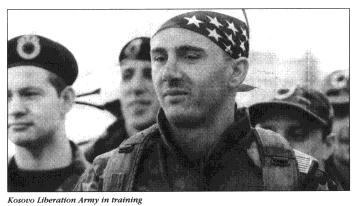

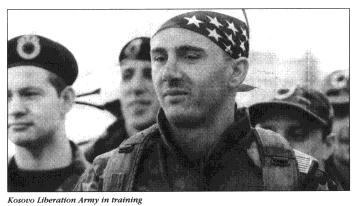

For the first half of the 1990s the movement took the form of passive resistance to the Serb state. People accepted this policy because they realised they were too weak to win in direct physical confrontation, but after the failure of the Dayton agreement in the mid-1990s to take Kosovan Albanian rights into account, there was growing support for the approach of armed groups, like the Kosovo Liberation Army.

Yet these groups also saw they were too weak to win if they took on the Yugoslav army by themselves. They therefore followed a strategy of seeking support both from nationalist groups inside Albania and among the Albanian minority in Macedonia. They also looked increasingly to drawing the US and other western powers into the conflict by provoking Yugoslav retaliation against Kosovan Albanian civilians. Their tactics included attacks not only on Serbian police and Yugoslav soldiers, but also on Kosovan Serb civilians (bombs in cafés, the kidnapping of ethnic Serb miners and so on). The strongly pro Kosovan Albanian Guardian journalist Jonathan Steele reported last year that in some villages not only were Serbs ‘ethnically cleansing’ Albanians, but the KLA was ethnically cleansing Serbs. This was the old logic of Balkan nationalism.

If the Nato forces give them some control in Kosovo, sections of the KLA will follow the same logic in the areas of Western Macedonia they claim for a Greater Albania. Such is the ethnic mix of Western Macedonia, they could not achieve their aims without the sort of ethnic cleansing the proponents of a Greater Serbia attempted in parts of Croatia and Bosnia. In the process, they would also create a situation where other powers with claims on Macedonia (Bulgaria and Greece) or even on Serbia (Hungary and Bulgaria) would be tempted to intervene, with even more ethnic cleansing.

Under such circumstances, there can be no excuse for any genuine socialist backing the KLA’s nationalism. To do so would be to line up with an ally of imperialism and a proponent of ethnic cleansing, even if on a smaller scale at the moment than Milosovic’s. Socialists certainly see a place for Kosovan self determination in a final, peaceful outcome for the region. It is difficult to see how Serbs and Albanians can ever live together peacefully unless they accept each other’s rights, and this means Serbs accepting the right of Albanians to establish a state of their own in Kosovo if they so desire. But it also means the Albanians in Kosovo and Macedonia guaranteeing to other ethnic groups, including the Serbs, their rights. Otherwise Kosovan self determination would simply mean the old Balkan game of one national group establishing a state, denying minority ethnic groups their rights, and leading to still more ethnic strife.

When early meetings of the Communist International discussed the Balkan question they concluded that the only way to satisfy the different demands for national rights was in the context of a socialist federation of the whole region and not through the further proliferation of rival capitalist states, each entrapping embittered national minorities within them. But all these arguments are purely hypothetical while the Nato war against Yugoslavia continues, for it is reducing Kosovo and much of Serbia to one great bomb site, where national rights for anyone are a sick joke. Only if the war leads to revolutionary developments in countries like Greece will things be otherwise. Meanwhile, the responsibility of socialists in the bombing states is to do our utmost to bring the war to an end.

Top of the page

Last updated on 21 December 2009

‘The bourgeoisie of each country is ... asserting that it is out to defeat the enemy, not for plunder and the seizure of territory, but for the liberation of all other peoples except its own.’ Quotations from Lenin can appear like biblical texts, presented as sacred truths at the beginning of a holy sermon. But this one, written as the horror of the First World War was casting its bloody shadow across Europe, is relevant today, when Nato politicians tell us this is the first ‘humanitarian war’ and many who claim to be on the left concur.

‘The bourgeoisie of each country is ... asserting that it is out to defeat the enemy, not for plunder and the seizure of territory, but for the liberation of all other peoples except its own.’ Quotations from Lenin can appear like biblical texts, presented as sacred truths at the beginning of a holy sermon. But this one, written as the horror of the First World War was casting its bloody shadow across Europe, is relevant today, when Nato politicians tell us this is the first ‘humanitarian war’ and many who claim to be on the left concur.