To correct the diagram given above we must begin by ascertaining the content of the concepts dealt with. By commodity production is meant an organisation of social economy in which goods are produced by separate, isolated producers, each specialising in the making of some one product, so that to satisfy the needs of society it is necessary to buy and sell products (which, therefore, become commodities) in the market. By capitalism is meant that stage of the development of commodity production at which not only the products of human labour, but human labour-power itself becomes a commodity. Thus, in the historical development of capitalism two features are important: 1) the transformation of the natural economy of the direct producers into commodity economy, and 2) the transformation of commodity economy into capitalist economy. The first transformation is due to the appearance of the social division of labour—the specialisation of isolated [N. B.: this is an essential condition of commodity economy] separate producers in only one branch of industry. The second transformation is due to the fact that separate producers, each producing commodities on his own for the market, enter into competition with one another: each strives to sell at the highest price and to buy at the lowest, a necessary result of which is that the strong become stronger and the weak go under, a minority are enriched and the masses are ruined. This leads to the conversion of independent producers into wage-workers and of numerous small enterprises into a few big ones. The diagram should, therefore, be drawn up to show both these features of the development of capitalism and the changes which this development brings about in the dimensions of the market, i.e., in the quantity of products that are turned into commodities.

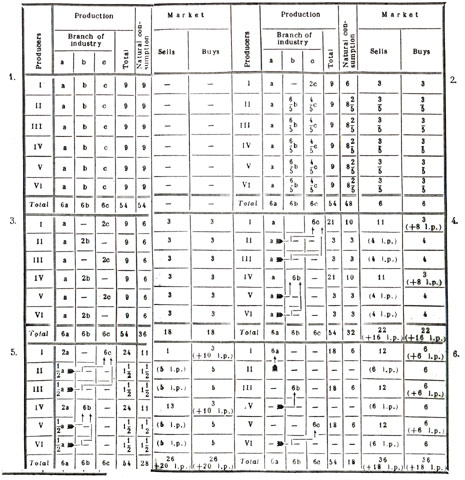

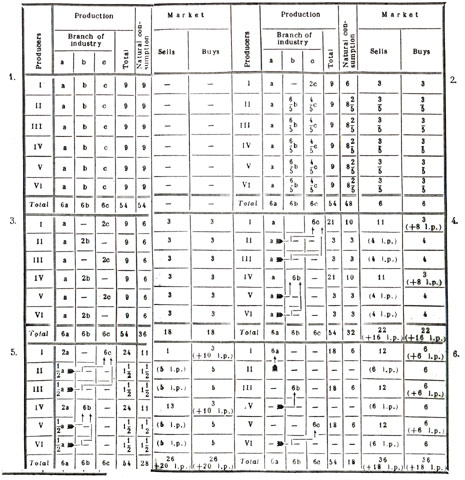

The following table[1] has been drawn up on these lines: all extraneous circumstances have been abstracted, i.e., taken as constants (for example, size of population, productivity of labour, and much else) in order to analyse the influence on the market of only those features of the development of capitalism that are mentioned above.

Let us now examine this table showing the consecutive changes in the system of economy of a community consisting of 6 producers. It shows 6 periods expressing stages in the transformation of natural into capitalist economy.

1st period. We have 6 producers, each of whom expends his labour in all 3 branches of industry (in a, in b and in c). The product obtained (9 from each producer: a+b+c =9) is spent by each producer on himself in his own household. Hence, we have natural economy in its pure form; no products whatever appear in the market.

2nd period. Producer I changes the productivity of his labour: he leaves industry b and spends the time formerly spent in that industry in industry c. As a result of this specialisation by one producer, the others cut down production c, because producer I has produced more than he consumes himself, and increase production b in order to turn out a product for producer I. The division of labour which comes into being inevitably leads to commodity production: producer I sells I c and buys I b; the other producers sell I b (each of the 5 sells 1⁄5 b) and buy 1 c (each buying 1⁄5 c); a quantity of products appears in the market to the value of 6. The dimensions of the market correspond exactly to the degree of specialisation of social labour: specialisation has taken place in the production of one c (I c=3) and of one b (1 b =3), i.e., a ninth part of total social production [18 c (= a = b)], and a ninth part of the total social product has appeared in the market.

3rd period. Division of labour proceeds further, embracing branches of industry b and c to the full: three producers engage exclusively in industry b and three exclusively in industry c. Each sells I c (or I b), i.e., 3 units of value, and also buys 3—1 b (or I c). This increased division of labour leads to an expansion of the market, in which 18 units of value now appear. Again, the dimensions of the market correspond exactly to the degree of specialisation (= division) of social labour: specialisation has taken place in the production of 3 b and 3 c, i.e., one-third of social production, and one-third of the social product appears in the market.

The 4th period already represents capitalist production: the process of the transformation of commodity into capitalist production did not go into the table and, therefore, must be described separately.

In the preceding period each producer was already a commodity producer (in the spheres of industry b and c, the only ones we are discussing): each producer separately, on his own, independently of the others, produced for the market, whose dimensions were, of course, not known to any one of them. This relation between isolated producers working for a common market is called competition. It goes without saying that an equilibrium between production and consumption (supply and demand) is, under these circumstances, achieved only by a series of fluctuations. The more skillful, enterprising and strong producer will become still stronger as a result of these fluctuations, and the weak and unskillful one will be crushed by them. The enrichment of a few individuals and the impoverishment of the masses—such are the inevitable consequences of the law of competition. The matter ends by the ruined producers losing economic independence and engaging themselves as wage-workers in the enlarged establishment of their fortunate rival. That is the situation depicted in the table. Branches of industry b and c, which were formerly divided among all 6 producers, are now concentrated in the hands of 2 producers (I and IV). The rest of the producers are their wage-workers, who no longer receive the whole product of their labour, but the product with the surplus-value deducted, the latter being appropriated by the employer [let me remind you that, by assumption, surplus-value equals one-third of the product, so that the producer of 2 b (—6) will receive from the employer two-thirds— i.e., 4]. As a result, we get an increase in division of labour—and a growth of the market, where 22 units now appear, notwithstanding the fact that the “masses” are-impoverished”: the producers who have become (partly)...

I—II...—VI are producers.

a, b, c are branches of industry (for example, agriculture, manufacturing and extractive industries).

a = b = c = 3. The magnitude of value of the products a = b = c equals 3 (three units of value) of which 1 is surplus-value.[2]

The ‘market’ column shows the magnitude of value of the products sold (and bought); the figures in parentheses show the magnitude of value of the labour-power (=1. p.) sold (and bought).

The arrows proceeding from one producer to another show that the second, wage-worker for the second.

Simple reproduction is assumed: the capitalists consume the entire surplus-value unproductively.

... wage-workers no longer receive the whole product of 9, but only of 7—they receive 3 from their independent activity (agricultural—industry a) and 4 from wage-labour (from the production of 2 b or 2 c). These producers, now more wage-workers than independent masters, have lost the opportunity of bringing any product of their labour to the market because ruin has deprived them of the means of production necessary for the making of products. They have had to resort to “outside employments,” i.e., to take their labour-power to the market and with the money obtained from the sale of this new commodity to buy the product they need.

The table shows that producers II and III, V and VI each sells labour-power to the extent of 4 units of value and buys articles of consumption to the same amount. As regards the capitalist producers, I and IV, each of them produces products to the extent of 21; of this, he himself consumes 10 [3 ( =a)+3 ( =c or b)+4 (surplus-value from 2 c or 2 b)] and sells lit; but he buys commodities to the extent of 3 (c or b)+8 (labour-power).

In this case, it must be observed, we do not get complete correspondence between the degree of specialisation of social labour (the production of 5 b and 5 c, i.e., to the sum of 30, was specialised) and the dimensions of the market (22), but this error in the table is due to our having taken simple reproduction,[3] i.e., with no accumulation; that is why the surplus-value taken from the workers (four units by each capitalist) is all consumed in kind. Since absence of accumulation is impossible in capitalist society, the appropriate correction will be made later.

5th period. The differentiation of the commodity producers has spread to the agricultural industry (a): the wage-workers could not continue their farming, for they worked mainly in the industrial establishments of others, and were ruined: they retained only miserable remnants of their farming, about a half (which, we assumed, was just enough to cover the needs of their families)—exactly as the present cultivated land of the vast mass of our peasant “agriculturists” are merely miserable bits of independent farming. The concentration of industry a in an insignificant number of big establishments has begun in an exactly similar way. Since the grain grown by the wage-workers is now not enough to cover their needs, wages, which were kept low by their independent farming, increase and provide the workers with the money to buy grain (although in a smaller quantity than they consumed when they were their own masters): now the worker produces 1 1⁄2(=1⁄2 a) and buys 1, getting in all 2 1⁄2 instead of the former 3 (=a). The capitalist masters, having added expanded farming to their industrial establishments now each produce 2 a (=6), of which 2 goes to the workers in the form of wages and 1 (1⁄3 a)—surplus-value—to themselves. The development of capitalism depicted in this table is accompanied by the “impoverishment” of the “people” (the workers now consume only 6 1⁄2 each instead of 7, as in the 4th period), and by the growth of the market, in which 26 now appear. The “decline of farming,” in the case of the majority of the producers, did not cause a shrinkage, but an expansion of the market for farm produce.

6th period. The specialisation of occupations, i.e., the division of social labour, is completed. All branches of industry have separated, and have become the speciality of separate producers. The wage-workers have completely lost their independent farms and subsist entirely on wage-labour. We get the same result: the development of capitalism [independent farming on one’s own account has been fully eliminated], “impoverishment of the masses” [although the workers’ wages have risen, their consumption has diminished from 61⁄2 to 6: they each produce 9 (3a, 3b,2 3c) and give their masters one-third as surplus-value], and a further growth of the market, in which there now appears two-thirds of the social product (36).

[1] See table on pp. 96–97.—Ed.

[2] The part of value which replaces constant capital is taken as unchanging and is thereto, ignored.—Lenin

[3] This also applies to the 5th and 6th periods.—Lenin

| IV | | | VI |

| Document Index | ||

| < Backward | Forward > | |||||

| Works Index | | | Volume 1 | | | Collected Works | | | L.I.A. Index |