MIA > Archive > M. Philips Price

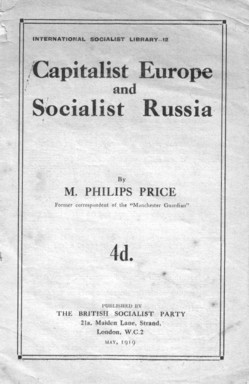

Source: A four-penny pamphlet, datelined Moscow, November 1918, published in May 1919 by the British Socialist Party, 21a Maiden Lane, Strand, London WC2; publication no. 12 of the International Socialist Library. Morgan Philips Price is noted as the ‘Former correspondent of the Manchester Guardian’.

‘Revolution is the locomotive of history.’ — Karl Marx.

After the outbreak of the European war the English and French public were informed by those who directed public opinion in their countries that the ‘new era’ in Russia had begun. That new era, so it was said, had taken the form of a national renaissance and a patriotic enthusiasm which was sweeping the land and was an indication that the government of the Tsar, in a paternal manner perhaps, but more or less accurately represented the interests of the people it ruled. So firm was this conviction in the minds of the English ruling classes that Lord Milner, in a statement made to the press on his return from his mission to Russia in February 1917, declared that the only discontent he observed in the country came from those who proclaimed that the war was not being waged sufficiently energetically. And so it may have seemed to those who could not look beyond the velvet cushions of the palaces and embassies that lay on the banks of the Neva. To them indeed Russia may have appeared a land of ‘law and order’, where the people’s one end was ‘war to the bitter end’. And even when the March Revolution came, after a few uneasy moments, trying to explain away inconvenient facts, the British and French diplomats and financial wire-pullers succeeded in persuading themselves that in Russia nothing had happened; that the people were as ready as ever to fight along with the Allies till the knock-out blow had been delivered; that only a few German agents and Jews were talking peace, land and labour reforms, instead of about the war; that Russia in fact was still a land of ‘law and order’.

But when the October Revolution came, at once the English and French press was filled with horrible stories about the servants of the revolutionaries, the massacres of the propertied classes, the ruin of the innocent ministers of Kerensky and of the Tsar’s regime, about the anarchy in the streets of Petrograd and the chaos in the provinces.

Having been a land where apparently everyone was contented with the government and the existing order, Russia became all of a sudden a land of ‘anarchy and chaos’, where a large section of the community were so discontented that they were by violent methods removing that existing order and trying to replace it by something else. What had happened to cause this astonishing change? Was there really ‘civil peace, law and order’ in Russia under Tsarism and Kerensky, and did ‘anarchy and chaos’ and class warfare commence with the October Revolution? Let us see first what actually were the conditions under which the population of Russia lived before the revolution.

First let us briefly examine the principal elements in Russian rural and urban society, and their relations to each other, in order to see what were the circumstances which made a political upheaval inevitable. Central and Northern Russia consists of wide areas of agricultural land and forests dotted with towns and other centres, where industry has developed on the European factory system. Parallel with and dependent upon the larger factories are many subsidiary industries, which are still carried on in the villages on the old domestic industrial system. In many areas the factories are scattered about among the villages and thus there is a continual intercourse between the workers on the field and the toilers in the workshop. Most peasant families have one or two members working in cotton, timber or leather mills near by the village or preparing the raw materials for the factory in some little cooperative ‘artel’. These workers still retain their land allotments, which they work in spring and autumn side by side with their relations and fellow-villagers, who spend all their time on the land. In the big towns, however, where the large metal and engineering industries are situated, there is a class of skilled workers who by the specialised nature of their craft have lost all touch with the land. Thus the labouring population of North and Central Russia contains three elements; the pure peasant type, the skilled artisan, and the half-peasant half-proletarian type. The essential feature about all three of them is that they are closely united by common interest. All of them suffered in different ways under the same yoke of Tsarism. The pure urban proletariat was a wage-slave of the most abject type. His conditions of labour were imposed on him by his employer. Association with the object of bettering his conditions was denied him. In the year before the first revolution not more than 300,000 members of trades unions were registered in all Russia, and they were put under close police supervision and only allowed to concern themselves with such things as insuring, at their own expense, their members against sickness and accident. Their labour was mercilessly exploited. As an example of this one may look at the wage returns and profits of 142 industries in the Moscow industrial area for the last three years of Tsarism. In 1913 the average wage per month was 213 roubles, in 1914 221 roubles, in 1915 251 roubles, that is, in the first two years there was an increase of one per cent and in the second 15 per cent. During the same period the prices of seven necessaries of life had risen by 23 per cent in the first two years and 79 per cent in the second two. But with the profits of the owners of these industries the picture was very different. For 1913 the net profits on the capital invested were 14.6 per cent, for 1914 16.5 per cent, for 1915 39.7 per cent, showing the total increase in the rate of profit throughout the three years of 171 per cent! The Russian capitalist class had long been demoralised by high protective tariffs, by the absence of competition, by monopoly rights acquired from Tsardom for the payment of bribes and indulgences to ministers. In this also they shared the spoils with foreign banks and company-promoting syndicates. Many of the great Southern and Central railways were monopoly concessions of French banks, many mines in the Urals and Siberia of English and German companies. Two-thirds of the capital invested in the Don iron mines and smelting works were owned in France and Belgium. These syndicates earned in the three years preceding the war an average of 32 per cent on their capital and one of them earned 121 per cent! There was absolutely no control of profits or of the conditions of labour in these industrial undertakings. The labourer was left to the mercy of the law of supply and demand. A judicious bribe to a Tsar’s minister gave the right to levy tribute on the Russian public in freights, rates and other imposts in the public services to an unlimited degree, and the understanding would be given at the same time that none should interfere on behalf of the Russian labourer.

No less happy were the conditions of that element in the community, the sole means of livelihood of which was drawn from labour on the land. Of the 393 million dessatines of land only 138 million belonged to the peasant and the rest was the property of private landowners, the Tsar, the imperial family, the ministers and church. Only upon one-third of the land of Russia was the peasant assured of the fruits of his labour. On the remaining two-thirds he had to work for the landlord and received only a small fraction of the profits. The bulk of the produce went to the landlords, who exported it at prices subsidised through export bounties by the government. Thus it often happened that in years of great want and famine among the peasants of one part of Russia, the landlords of another part were exporting corn to the Western countries. In 1913, 500 million poods of corn, that is, one-third of the total harvest, was exported in this manner. The Russian peasant became systematically underfed and had to depend on the landlord for all sorts of indulgences. Though socially supposed to be emancipated from serfdom, in reality he was nothing more than an economic serf.

Thus the urban workmen, the peasant and the unskilled man who spent half his time in the village and half in the factory, were all oppressed under the same system of exploitation. All three had common interests in seeing the removal of the political supports that bolstered up this system. None of them had anything to lose by a violent overthrow of Tsarism and the expropriation of landlords and industrial capitalists. All of them had everything to gain by the immediate establishment of a new social order.

Other circumstances also combined to create at the bottom of Russian society a huge compact mass of politically-explosive material. The urban workers in Russia have never been split up into a number of guilds, crafts and trade unions, each running their own professional interests, as in Western Europe. Tsarism suppressed even trade unions, while the rapid growth of the European factory system in rural surroundings supplied the owner with semi-serf unskilled labour straight from the land. This type of labourer, conscious of his serf conditions, saw his only hope in direct political action. He therefore laid on one side hopes of bettering his conditions by the formation of guilds and professional unions for economic ends. He formed a united revolutionary front with his comrade, the skilled labourer and the poor peasant, and did not allow the ranks to be broken by quarrels between professional grades of labour about the economic privileges of one section of the working classes over another, as is so often the case in Western Europe. In addition to this the proletarian mass of Russia was enriched by the presence in it of a considerable intellectual element. In Western Europe the propertied classes have always been quick to draw out from the ranks of labour the best and most capable elements, to induce them by advantageous offers to betray their class and to serve the interests of the class above them. But Tsarism, with an oriental disdain for all but those who rule by the ‘will of God’, laid its heavy hand on proletarian and intellectual alike. The closest contact between these two elements of the community was therefore maintained, thus adding another social recruit to the revolutionary army.

All these facts permit one to draw three conclusions. Firstly, that those who fed themselves on the idea that Russia before the revolution only needed a little ‘democratic’ change, a ‘constitutional monarchy’ perhaps, or a government by ‘live elements’, which meant landlords and war profiteers, and that the people were ready to fight indefinitely in a war for secret treaties, made by foreign governments, had either wilfully or by neglect failed to appreciate the most fundamental facts in Russian life; secondly, that the presence of a semi-oriental despotism and a demoralised and incompetent capitalist class, side by side with an immense discontented, unskilled, labouring mass, living both in town and villages and united in one common political aim, created conditions favourable to violent political upheaval; thirdly, that the groundwork for rapid social changes had been ripening in Russia for many years past and that revolution was ready to break out there long before such an event was probable in any neighbouring country. Of course one would not expect the controllers of Western Europe financial capital, company promoters and owners of the press syndicates, who were directly interested in the maintenance of Tsarism and the system of exploitation of the Russian workers and peasants, to see the powerful economic forces working for these changes. But these forces were there nevertheless and, when they came to the surface, they showed themselves as one of the most decisive factors in world politics.

Having briefly examined the economic and social conditions in Central Russia before the revolution, and having seen how these conditions made revolutionary changes inevitable, let us now see how these changes were effected in their different stages. We shall be better able then to compare the ‘law and order’ of Tsarism and of the transitionary stage of the Kerensky government with the ‘anarchy and chaos’ of the new regime. Now it was clear to any unprejudiced observer that even in the first days of the March Revolution the great peasant–proletarian–soldier mass, which had created the first Petrograd Soviet and was already imposing its will upon the timid Provisional Government, was bent on bringing about immense social change in the country. The complete breakdown, as the result of the war, of the corrupt and incompetent bureaucracy of Tsarism, which based its authority on old feudal privileges, opened for these masses a wide perspective. The skilled factory labourers and the half-proletarian unskilled workers now had the chance by united action of freeing themselves from the ever-increasing exploitation under which they had lived and by which they were being threatened with famine. Something had to be done to raise their purchasing power so that they could cope with the ever-increasing cost of living, which far overstepped the meagre increase in their wages. Something had to be done to shorten their hours, if only as the first step of insuring greater efficiency of labour and thereby an ultimate increase in production. Lastly, something had to be done to stop profiteering and to ensure that the products of the factory were properly and evenly distributed among the rural population, in exchange for which food could be obtained for the starving towns. This last meant that the factory-owners and swarms of middlemen and parasites, who were buying up and speculating in these necessaries of life, should be put under control. Instinctively the workmen in the first Petrograd Soviet and later in the thousands of provincial Soviets all over the country felt the imperative need for action on these lines.

The peasant also saw in the collapse of Tsarism the possibility of at last freeing himself from his conditions of economic serfdom under the landlord. He saw that he could demand the recognition of the principle for which he had always contended, namely, that the land should not be the property of any individual, that it should belong to the whole community, who should allow its use to all citizens, and that property in land should be converted into property in the products of labour from the land. This meant the liquidation of the great estates, the passing of the latifundia to the peasant communes, and the domain lands to some public authority.

Lastly, it was clear both to peasant, to urban worker and to half-proletarian that unless there was speedy peace between Russia and the peoples of the Central Powers, a terrible catastrophe would overtake the country, the shortage in food and raw materials would become a famine, speculation would increase to social parasitism, and the whole of Russia would become the prey to foreign banking capital, to be partitioned at pleasure between London, Berlin, Paris and New York.

It is not necessary here to describe the steps taken by the first All-Russian Soviet Executive with the unwilling assistance of Kerensky’s bourgeois Provisional Government to bring about international peace by a ‘democratic’ Socialist conference. The failure of these attempts during the summer of 1917 only dashed the hopes of emancipation which the urban workers and the peasants had seen maturing for them earlier in the year. The policy of coalition between the ‘Socialist’ leaders and the representatives of the Russian propertied classes in the Provisional Government led to the complete shelving of all reforms and the ever-increasing degradation of the labourer and the peasant under the iron heel, not only of the ‘patriotic’ Russian industrialists and landlords, but also of the increasingly powerful ‘financial capitalists’ of the Allied countries, who like vultures were standing round a weak horse hoping it would die.

As soon therefore as the restraints imposed by the autocracy on political and economic association had been removed, the urban proletariat commenced to mobilise itself politically into Soviets, professionally into trade unions, and industrially into shop-stewards’ committees. By the middle of the summer of 1917 the All-Russian Professional Alliances was formed with a membership of nearly two million. Large increases in wages for metalists, cotton-mill hands, railwaymen and miners were demanded and obtained. But the effect of this on the conditions of the workers was nil. The factory-owners, free from all restraints, only raised wages in order to increase prices and thus forced the burden upon the workers again. Prices of food and necessaries continued to tower, forcing the government to inflate still further the currency. A bottomless swamp was created into which the urban worker was sinking deeper and deeper every day. The Provisional Government’s attempts to stop the ‘dance of the paper milliards’ and to control the war profiteers were a dismal failure. The industrial syndicates, which were formed under government control to concentrate the production of and supervise the distribution of the principal raw materials of industry were in practice left to the tender mercies of the bank directors and factory-owners themselves. The latter easily succeeded in influencing the bourgeois members of the Provisional Government in the way they desired. Nor did the government’s attempts to stop profiteering by introducing direct graduated taxation have any result. Capitalists only drew millions of paper out of the banks, did their own banking and gave incorrect returns. More than once during the summer the Petrograd workmen tried to take the law into their own hands and through their shop-stewards’ committees to control production in the interests of the workers and the consumers. But in every case the Menshevik members of the Provisional Government interfered with promises that they would ‘influence’ the industrialists and bourgeois members of the Provisional Government in the desired direction. The Menshevik Minister of Labour, Skobelev, however, showed not only that he could not influence the capitalists, but that he was himself unconsciously their tool. For he hurried through a law forbidding the shop-stewards’ committees to interfere with the work of the owners of the factories. But as if in defiance of even the most moderate reforms the owners began a campaign of sabotage. Several coal mine areas were closed down on the Don during the summer of 1917, while the Moscow cotton manufacturers threatened to stop the mills if they were not allowed a ‘free hand’. Thus the industrial anarchy increased week by week and with the coming of the winter the urban worker and the half-proletarian saw nothing before him but cold and famine.

Nor was the peasant’s lot any brighter. During the spring Victor Chernov, the Minister of Agriculture in the Provisional Government, had set up ‘land committees’ in each province, which were temporarily to take on account all landlords’ land and to work it in the interests of the community, pending the final decision of the Constituent Assembly. This pacified the peasants for a time. But as soon as it was known that the right to buy and sell land was restricted, the bankers and Cadet politicians commenced a furious attack on Chernov, who was compelled to resign and his provisional land scheme collapsed with him. Then the landlords got bolder and commenced a hue and cry against the land committees. Their members were arrested by parties of officers, who had formed into secret White Guards, they were thrown into prison, some of them shot, and in many provinces the whole organisation was broken up. The peasants replied by sacking many landlords’ mansions with the aid of their soldier sons, who had returned from the front. A wave of agrarian pogroms swept over the governments of Tambov, Penza and Voronezh in September 1917. The landlords would not give way one tittle of their privileges in favour of the rural communes; the peasants on the contrary were determined to secure the recognition of their contention that the land belongs to the community that works it. Two irreconcilables were thus clashing and, as a result, complete anarchy was reigning in the central provinces of Russia on the eve of the Bolshevik revolution. The Kerensky government, brought into existence by the popular uprising in March on the understanding that it would remove the economic and social privileges of the Russian landlord and capitalist class and of foreign banking syndicates, had not only failed to accomplish anything but had intensified the very evil which was rampant under Tsarism and had thus made the outlook of the masses more hopeless than ever.

It is not surprising therefore that when on 25 October 1917 the revolutionary workers and soldiers were in possession of Petrograd for a second time and the Council of the People’s Commissaries was set up in the Smolny Institute, this body began immediately to tackle the three problems, the settlement of which was the only guarantee that the country would be lifted out of anarchy and chaos into some form of law and order. There were three great problems. Firstly, the urban workers demanded public ownership of industry, the suppression of private profiteering and speculation, and a minimum standard of living for all the workers, as servants of the state. Secondly, the peasants demanded that the land should become public property and that no one should derive income from it by using the labour of others. Thirdly, both peasants and urban workers saw that peace with the peoples of those countries with which the Russian workers and peasants had for three years been fighting, was necessary in order to make it possible to solve the first two problems. Therefore the first decree issued by the Council of the People’s Commissaries on 26 October was the offer of an armistice between the European armies at war. I will not deal here with the history of the peace negotiations, but will only remark that the necessity of liquidating the imperialist war was dictated to the Soviet Government by the necessity of conducting as peacefully and orderly as possible the social revolution in Russia, which had already begun before October 1917, and was only accelerated by the economic exhaustion caused by the war. The Bolshevik party had to deal with the elementary impulses of the tortured and discontented masses, and directed those impulses into orderly, constructive channels.

While Trotsky was negotiating at Brest-Litovsk and sending out psychological messages to the workers of Western Europe, the process of orderly reconstruction had already begun in Russia. On the second day after the October Revolution the Council of the People’s Commissaries issued the decree on ‘workmen’s control’, which gave the shop-stewards’ committees the right to regulate the work of their respective factories. The owners of the factories were not removed; there was no expropriation or nationalisation as yet. The decree gave the men’s committees the right to examine the books, countersign orders and control the removal and arrival of goods and raw materials within the precincts of the factories. In each industrial district a joint Council of Shop-Stewards’ Committees and Professional Alliances was formed, so as to coordinate policy and prevent conflict between industry and craft. The workers in this stage of the revolution did not yet think of going beyond the stage of effectively controlling the capitalist. They did not feel themselves strong enough at this moment to take over and work the industries of the country. The economic apparatus for production and distribution on a public basis had not yet been prepared, and meanwhile the proletariat had not the technical staff at its disposal. The latter was to a large extent still under the influence of the capitalists and thus the proletariat was in danger of economic isolation. It was however possible by the establishment of workers’ control to go one step beyond the point reached by the March Revolution. We have seen above how the workers in their newly-formed professional alliances had in the time of the Kerensky government dealt with the question of wages and hours. But neither the shop-stewards’ committees nor the professional alliances had yet been able to tackle the sabotage and lockouts of the owners. After the October Revolution the first step to solving this problem was taken by introducing a semi-craft, semi-industrial body, which consisted of the union of the shop-stewards’ committees, as representative of labour organised on an industrial basis, and of the professional alliances, as representative of labour organised in crafts. It was the duty of this body to establish effective control over those employers who declined to put up with the new conditions. Thus the Russian workers acquired the right of joint management along with the employers of the factories and so reached at one bound the position foreshadowed for England ‘after the war’ in the Whitley report.

But their experience should serve as a good object lesson to those who still think that it is possible to make the capitalist lion lie down with the proletarian lamb under any condition except that the lamb shall be inside. For the moment they began to try their ‘control’ of the employers they had a hornets’ nest about their ears. The technical staff, which had been previously bought by the employers, struck work at the word of command and the private banks supplied the means for financing the sabotage. Industries were brought to a standstill and a deadlock was reached. Thus the policy of trying to ‘reconcile employer and employed’, capitalist exploiter with proletarian exploited, was bankrupted from the outset. No sooner had the Russian workers completed one stage of their journey than the merciless pressure of the revolutionary current forced them on to another. The facts had to be faced. No cooperation with the propertied class was possible. The conflict of interests was such that either the workers or the capitalists must rule. Those who naively thought, like the small middle-class ‘democratic’ parties, that it was possible by parliamentary methods, by the suffrage, to free the workers from wage-slavery and the peasant from the exploitation of the landlord had to learn from the Russian revolution that they were following phantoms. For the experiences after October 1917, showed, as it must show in every other country, that the capitalist class, which has been brought up for generations to believe that it alone has the right to rule, is more jealous of its ‘divine right’ than any Stuart king. It had in Russia no more intention of submitting to the will of the ‘democratic’ majority of a parliament, trying to restrict its monopoly power, than a fox would have of willingly entering a trap. The utter bankruptcy of the Bolshevik decree on workers’ control showed what hopes there were of inducing the Russian propertied classes voluntarily to commit suicide. And what was true of Russia then is likely to be doubly so now for Western Europe, where the system of financial capital is more powerfully entrenched. Martial law, secret White Guard organisations, the financing of sabotage, the policy of breaking up labour organisations by hooligans connived at by the police — all these methods find much more favour with the propertied classes and their agents than obedience to resolutions passed by ‘democratic’ parliamentary majorities. And the only argument that they can understand, as the history in Russia of the Kornilov, Kaledin, Dutov and Krasnov adventures all show, is the iron dictatorship of the working classes. After the October Revolution therefore there was only one choice for the Russian proletariat. If it wished to raise itself above wage-slavery it had to take industrial production and commercial distribution entirely into its own hands. In order to carry this out sabotage had to be stamped out, the power of the propertied classes over the clerical and technical staffs broken, and the banks, those fountain-heads of the counter-revolution, declared public property.

From the first day of the October Revolution the state bank had been occupied by red guards, a commissary had been put in, and all issues of paper money to the private banks strictly controlled. In Russia, it should be remembered, the private banks were wholly dependent on the state bank for the issue of paper currency. The occupation, therefore, of the state bank shut off their cash supply. But the private banks had taken the necessary precautions. Already scenting danger in September, the bank directors had, while Kerensky’s government still existed, secured from the state bank cash advances variously estimated at from a quarter to half a milliard roubles. They were therefore guaranteed for some weeks. As soon as the state bank was occupied by the red guards and workmen’s control established in the factories, the private banks instantly broke off all connection with the industries which they had hitherto been financing and the workers were left without wages. More than that, the millions of roubles which the bank directors now held, went to support the families of the clerical and technical staffs of the railways and industries who struck work at the word of command, thus condemning the whole country to a complete stoppage of its economic life. Large amounts of money also, under the direction of the French Military Mission, went to the Don and the Ukraine, where General Kaledin and the Rada were organising an army of officers and wealthy cossacks to invade Central Russia and re-establish the old government. It was laughable at the time to read the harrowing accounts circulated in the West European press of how the families of the Russian propertied classes, the intellectuals, technical staffs and officers were thrown starving on the streets of Petrograd and Moscow by the cruel Bolsheviks and forced to sell newspapers. As an actual fact they were the unhappy victims of the class war which had broken out with all its severity and bitterness, and were being offered up on the altar of the old economic system by the Russian capitalist class in its frantic endeavour to save its privileges. For a time these poor people lived comfortably on what had been advanced to them by the bank directors. Meanwhile the industries closed down and the workers suffered great privation. But when the sabotage money gave out, the coffers of the private banks emptied, and the state bank, occupied by the red guards, gave no further issues. Then after a few weeks the intellectual and technical staffs returned to work, and officers who had not sold themselves to the counter-revolution on the Don and the Ukraine, took civilian employment and the industries gradually reopened again.

But the question now arose how to finance these industries. Up till now this had been done by the private banks, who in actual fact controlled whole branches of industries most vital to the country. The process of financing carried on by the private banks was typical of the anarchical, anti-social methods of modern ‘financial capital’, which allows small groups of people to control the economic life of millions of workers and peasants. For this was the position. In January 1917, the paid-up capital of all the private banks in Russia amounted to 680 million roubles. Practically the whole of this was in the hands of 300 or 400 persons, who represented the bourgeoisie of Petrograd, Moscow and a few other centres. The deposits of these banks, lent mainly by the peasants, amounted to 6747 million roubles. Thus with a credit of nearly seven milliards the directors were able to enter into every conceivable form of adventure in the industrial and commercial sphere. And this they did without any control from outside. As the war consumed more and more of the material reserves of the country they engaged in an orgy of speculation and hoarded the stocks that remained. War profiteering reached unheard-of dimensions and the plunder in only a single year several times exceeded the insignificant paid-up capital of the banks.

Having decided to strike a daring blow for industrial liberty, the Russian working class was now faced with the problem that might have baffled the experienced bankers of any capitalist country. They had received the legacy of a four years’ war in an economically poorly-developed country, which had been still further sucked dry by the extortion and profiteering of private financial capital. Raw materials were fast disappearing and their place being taken by loan scrip and useless paper money, which made the state responsible for paying to the holders gold or materials at some future date. The position was as follows. At the date of the October Revolution the total state indebtedness of Russia amounted to 70 milliard roubles, which was made up roughly in the following way. Internal loans 15,700 million roubles, foreign loans 26,000 million roubles (this included debts to England 7500 million roubles, France 15,500 million roubles, Germany 1250 million roubles, other countries about two milliard roubles), paper money and short-term loans 28,300 million roubles. The interest and sinking fund for all this amounted to an annual charge of between four and four-and-a-half milliard roubles, which exceeded by one milliard roubles the whole annual revenue of the country in 1916! Even at the end of 1916, under Tsarism, the total indebtedness of the country reached 40 milliard roubles, the interest and the sinking fund on which swallowed up more than half of the annual revenue. It was clear therefore that long before the October Revolution Russia was bankrupt, and that part of the 26 milliard roubles lent by the Allies to Russia after 1916 was not lent under the expectation that it would be repaid in cash. These advances were obviously made by the ‘financial capital’ of England and France, because it was hoped in return to get control of the undeveloped natural wealth of the country, the railways, the mines and the projected public works. Otherwise no private financiers would have lent a penny on the security of the state budget as it was even a year before Tsarism fell.

The Russian working classes were not blind to the trap which the ‘financial capital’ of the world was preparing for them. They had set out to improve their conditions, to secure for the whole population of the country the profits of production, to stop the ‘dance of the paper milliards’, to distribute produce equitably, and to abolish profiteering. To do this they were forced to take over the private banks, to suppress the parasitical activities of their own ‘financial capital’ by annulling Russia’s internal war debt. But even after doing this, they were faced with a dead weight of interest and sinking fund on 26 milliard roubles of foreign war debt, in addition to a vast amount of paper money issued on the basis of treasury bills, many of which had been taken up in London and Paris. To pay this annual tribute would have meant either handing over the Russian state revenues to the Allied governments with power to impose taxation or else giving the latter a free hand to run the railways, the mines and the industries of the country, in order to draw from them the necessary revenues. But it was just in order to stop the process of running the public services and the vital industries of the country in the interests of a small class and to secure the profits of production for the whole people that the Russian working classes had made the revolution. Again there was only one choice. Either the debts to foreign ‘financial capital’ must be repudiated or the Russian workers must return again to industrial slavery. They did not hesitate for a moment, feeling that in this struggle for economic freedom they would be assisted by labour in England, France and Germany, who would themselves sooner or later be faced with the same dilemma as the result of the war and of the flooding of their countries with useless paper debt.

The last stage in the development of ‘financial capital’ had come. Like a ripe plum it was dropping to the ground. The storm of the imperialist war had shaken it from the tree of life to make way for the bursting shoot of the new economic order. The revolutionary masses of Russia read the signs of the times and reading them knew how to act.

Having blown up the fortress of the old system, under which they had suffered so long, by nationalising the banks and annulling the loans, the workers of Russia now turned their hands to the work of constructing the people’s palace of the new economic order. As one would naturally have expected, the greatest danger in the transition period came from those workmen’s councils, shop-stewards’ committees and professional alliances who ran their own provincial economic policies without considering the interests of the country as a whole. A guiding hand was necessary and that was found in the Supreme Council of Public Economy. This body came into existence early in January 1918. I well remember being present at its first meeting. A few workmen from the Petrograd and Moscow professional alliances and shop-stewards’ committees, together with some trusted revolutionary leaders and a few technical advisers who were not sabotaging, met together on the Tuchkov Naberezhnaya at Petrograd with the object of organising the economic life of the republic in the interests of the toiling masses. The task before them seemed superhuman. All around them was chaos, produced by the imperialist war and the orgy of capitalist profiteering. Famine, dearth of raw materials, sabotage of technical staffs, counter-revolutionary bands invading from the south, Prussian war-lords threatening from the west made the outlook apparently hopeless. Yet, nothing daunted, these brave workmen with no experience, except that derived from the hard school of wage-slavery and political oppression, set to work to reconstitute the economic life of a territory covering a large part of two continents. I saw them at that meeting draw up plans for the creation of public departments which should take over the production and distribution of the ‘key’ industries and the transport. Their field of vision ran from the forests of Lithuania to the oases of Central Asia, from the fisheries of the White Sea to the oil fields of the Caucasus. As they discussed these schemes, one was forcibly reminded that many of these very places, for which they were preparing their plans to fight famine and re-establish peaceful industry, were at that moment threatened by counter-revolutionary forces and by the armed hosts of the European war-lords, whose so-called ‘interests’ demanded that famine, anarchy and misery should teach the workers and peasants of Russia not to dare to lift their hands against the sacred ‘rights of property’. And the wind howled round that cold stone building which looked over the frozen Neva, and the winter snows were driving down the dismal streets, but these men, fired with imagination and buoyed up by courage, did not waver. They were planting an acorn which they knew would one day grow into an oak.

I saw them five months later at a big conference in Moscow. The Supreme Council of Public Economy had now become a great state institution and was holding its first All-Russian Conference. In every province in Central Russia and in many parts of the outer marches local branches had been formed and had sent their representatives. The first organ in the world for carrying out in practice the theory that each citizen is part of a great human family and has rights in that family, in so far as he performs duties to it, was being visibly created before my eyes in Russia. In the midst of the clash of arms, the roar of the imperialist slaughter on the battlefields of France, the savagery of the civil war with Krasnov on the Don and with the Czecho-Slovaks on the Volga, the Supreme Council of Public Economy was silently becoming the centre of the new economic life of the republic. It had been created while the more prominent political body, the Soviet, was struggling to preserve the existence of the republic from enemies within and without. The Supreme Council of Public Economy was the tool designed to create the new order in Russia; the Soviet was only the temporary weapon to protect the hands that worked that tool.

In tackling its problems not the least difficult was the economic separatism of the provinces and the conflict of interests between craft and industry. These problems hamper the labour movement in every country to a greater or less degree. How often in England has the multiplication of craft unions in the same industry or public service retarded the efforts of British labour to unite in a common policy for its emancipation? Yet in Russia the inexperienced, untried proletarian, freed from the traditions and encumbrances of an older, more archaic social system, succeeded in a few weeks in finding means to reconcile craft with industry. The first Councils of Public Economy in the provinces constituted themselves out of delegates sent by the professional alliances, to represent the economic interests of the workers organised in crafts, and an equal number of delegates from the shop-stewards’ committees to represent the interests of the workers organised in industries. To them were also added delegates from the local Soviets to represent the general political interests of the district, members of the local Soviet executives, which included numerous departments such as transport, produce, agriculture, commercial exchange, and also members of the workers’ cooperative societies and technical experts. The Supreme Council of Public Economy also in Moscow was formed from the same elements in their all-Russian capacity, drawn from the all-Russian union of professional alliances, the all-Russia shop-stewards’ union, the central Soviet executive, and the People’s Commissariats. Thus the machinery was created which enabled the interests of craft and industry to become reconciled and to work together in the common interest of reorganising the productive capacity of the country as a whole.

But more important even than the machinery, the spirit was there which kept the newly-formed professional alliances from pressing craft claims conflicting with general public interests, and which also prevented the shop-stewards’ movement from running those industries no longer needed by the community. The remarkable degree of cooperation observed between these two types of labour organisations after the October Revolution, a degree of cooperation not hitherto seen in any other country, can of course be attributed to the youth, one might almost say the immaturity, of the Russian industrial system. For the country has only just developed from a peasant-serf state, in which no traditions of craft unions have accumulated throughout the centuries. Thus the removal of trade-union restrictions on production and of the anti-social power of separate crafts, which in Western and Central Europe has required an imperialist war and the consequent flooding of the factories with unskilled labour, has been accomplished in Russia by a much simpler process. There the industries from the first have been largely supplied with the labour of peasants just released from serfdom and consequently untrained in any craft, except perhaps in some small domestic industry. It was very easy therefore for the professional alliances to organise the workers of a whole industry, say the textile or engineering trade, in such a way as to prevent each union from being split up into a number of smaller conflicting craft unions. The professional alliances in the course of 1918 in fact began to organise themselves on the basis of industries, leaving the shop-stewards’ committees as a sort of local autonomous units of these industries, working in close contact with them.

In addition to creating machinery for organising labour, the Supreme Council of Public Economy during the summer of 1918 began to tackle the problems of finance and distribution. It would take too long to enlarge upon these schemes fully, but I would point out that the general idea was to introduce a system of paying the worker partly in cash and partly in coupons, which he could exchange for food. This gradually affected the state finances by reducing the need for further currency issues, and it also made possible the introduction of a system of direct exchange. In order therefore to regulate exchange of produce between town and country, the whole urban proletariat and a considerable part of the rural population by the autumn of 1918 were classified into categories according to the amount and the intensity of the labour which each individual performed. Each individual then received food varying in amount according to these categories.

The machinery created for all this was only very gradually formed and the chief hindrance to its effective working was the disorders created by the German government and by the governments of the Allies, whose agents on the Don, the Volga, in Archangel and Siberia financed counter-revolutionary rebellions, blew up railway bridges, cut off food supplies and raw materials, and thereby created an anarchy which caused infinite suffering and privations to the workers and peasants of Central Russia throughout the greater part of 1918.

Nevertheless the Soviet Government of the Russian Republic, thanks to the discipline and political consciousness of its workers, after removing social parasitism and economic wage-slavery, set up the economic apparatus of the first Socialist state that has yet been created in the world. Its economic organs, elected by the workers, classed industrially and in technical groups, will one day become the supreme authority in the Socialist state. It will be the economic nerve-centre of public life and is destined to replace parliaments, elected on territorial basis without any qualifications to deal with problems of industry, transport, foreign trade, finance, etc. Parliaments become the easy prey of permanent executive departments, controlled by the propertied classes. The Supreme Council of Public Economy, on the other hand, in a Socialist state which is free from the need of defending itself from enemies without, combines legislative and executive functions and concentrates under its control the whole industrial and scientific apparatus of a modern state.

It now remains to see how the Soviet Government dealt with the third great problem of the revolution — the land. Measures for stopping the war had been taken the next day after the October Revolution. Shortly after that the skilled urban workers and the half-proletariat began to work their way up through workers’ control of industry to the creation of a great state apparatus for the public control of production and distribution. Now came the turn of the peasant. The decree on the land, which was issued on 28 October, handed over the great estates of the landlords, the former Imperial family, the cabinet ministers and the Church to provincial land committees. The latter now came back to the rights which the Kerensky government in the latter days robbed them of. It was necessary to act speedily. The peasants of Central Russia, exasperated at the delays in dealing with the land problem and knowing that intrigues were being carried on in Petrograd to prevent the land from getting out of the hands of the landlords and the big banks, to which much of the land had been mortgaged, had begun to take the law into their own hands. In several provinces the landlords’ mansions were burnt, the owners forced to flee, and the agrarian disorders threatened to ruin much agricultural stock of public value. The decree on land, issued by the Bolshevik Council of the People’s Commissaries, instantly quieted the peasants. They knew that the land would indeed be theirs if the land committees, which they controlled, had the handling of it.

But that did not solve the problem. The peasants themselves had no plan in their minds of how to deal with the land when they got it. Emancipated slaves who had only just cast off their chains, many of them had not yet learnt to act as men brought up in the atmosphere of freedom. The older generation of peasants and that part of the rural population which had never been in close contact with the half-proletariat, or with the urban skilled workers, could not think beyond the boundaries of the parish. To them it seemed that, as in the days of Tsarism, some beneficent power from above had given them the land. All they wanted therefore was to divide up the domain lands and add the portions of it to their allotments; to take the valuable livestock from the seigneur’s home farm and divide it equally among their families. It did not occur to them that by so doing they might ruin the great dairy industry, or might reduce the yield of cereals in the country by breaking up cultivation on an intensive scale. They did not see that to grab all the landlords’ latifundia (the second-rate land far away from the mansions) would also prevent other more needy peasants in provinces where land was scarce from improving their condition by emigration. All these facts were clear to the Bolshevik revolutionary leaders, however, for they at once took steps to deal with these elemental anarchist tendencies of the less politically-conscious part of the Russian peasantry, and when the third All-Russian Congress of Soviets met in January 1918, at once the representatives of the rural districts formed themselves into a special committee for working out a fundamental land law for the republic. For several weeks this commission sat in the Smolny Institute and at last produced the law which was passed by the Central Soviet Executive on 22 January 1918. The essential feature of the land law, which was the keystone to the new agrarian order, was contained in articles 1 and 2, which read as follows: ‘All private property in land, minerals, water, forests and the forces of Nature within the limits of the Republic are abolished for ever’, and ‘the land without any compensation to the owners (open or hidden) becomes the property of the whole people to be used for objects of common utility’. Thus at one blow the monopoly rights of those who held the source of all wealth was swept away and the Russian people acquired on those fateful days of January 1918 what no other working population has acquired in the world before — free access to the land. Moreover, the process was extremely simple. It was only necessary to declare all land public property and at once all the latifundia of the landlords, Imperial family, ministers and Church were automatically added to the miserable allotments which the peasants had received on emancipation; while the territorially small but economically important lands of the intensively cultivated domains were easily picked out, withheld from distribution among the peasants, and reserved for public development schemes. The Russian land law of January 1918 realised in practice what Mr Lloyd George in England in the years just preceding the war tinkered at but had not the courage to carry out. For by the Russian method there was no undeveloped land tax and unearned increment tax at a modest one to ten per cent. The Soviet Government took the bull by the horns and, by a simple hundred per cent tax, put an end to all profit-making in land at the public expense. Thus the Russian peasants were freed from the luxury of maintaining landlords, even in a form tamed and chastened by taxation. In other words, landlords as a social and economic factor simply ceased to exist.

Nor had the landlords any reason to be anything but thankful to the Bolsheviks, since all through the summer of 1917, while Kerensky’s government was vacillating, they were being threatened with pogroms and massacre by the morose and sullen peasantry. The land law enabled them quietly to disappear from the scene in an orderly legal manner. Nor were they cruelly treated by the law. They had the right to apply through the provincial land committees of the Peasants’ Soviets for that amount of their former land which they were capable of working with their own labour. If any landlord was old, infirm or unable for any reason to work, he was under article 8, section 1, given the right ‘to receive a pension on the scale of that granted to a disabled soldier’. Thus the libels circulated outside Russia that the Soviet Government threw out the landlords from their mansions to starve is seen on examination of the facts to be false. In those places where outrages did occur, they were due to peasantry who, as a result of excessive exasperation, had got out of hand and disobeyed the Bolshevik government authorities, or else they were due to provocative acts on the part of the landlords themselves.

Now what was the system which the new land law established for the distribution of land among the peasants? It was easy to break up estates, but difficult to create a new agrarian system which would not lower agricultural productivity and thus intensify the famine. Under section 2 of the land law a scheme was drawn up which provided for the order in which land allotments should be made. First in the scale came the state land departments, local and central, and public organisations working under their control. They were to be the first to have the right to withhold land from distribution among the peasants, in order to open experimental stations, intensive cultivation farms, or to run the domain homesteads for purposes of general public utility. Next in order came private societies and associations, and here preference was given to the ‘labour commune’, that is, to groups of peasants or urban workers’ families who should agree to work with common livestock and by common labour a given tract of land, to divide the products for their families and the profits from their sales in common. These new forms of communes were really large farms organised on a cooperative basis, both for production and consumption. They were admirably suited for the work of taking over the landlords’ domains and the home farms and for providing, under control of the state food department, the necessary agricultural produce for the urban population. Next in order came the old Russian peasant commune, which could, after the former categories had been satisfied, receive additions to the old allotments, which had been parcelled out in 1861. This old type of commune represents a much more archaic system of husbandry — a system under which the land is divided equally, but each family maintains its separate stock and farms independent of its neighbours. It has the disadvantage of splitting up the land into small isolated patches with the object of preventing any member of the commune from obtaining advantage over another member. It has none of the advantages of a common system of husbandry. The new land law thus did everything to encourage the new type of commune and to discourage the old. During the course of the summer of 1918 many hundreds of the new type were created in the central provinces by soldiers and sailors discharged from the old army, by skilled urban workers who, as a result of the famine in industrial raw products, had been thrown out of work, and by the half-peasant half-proletarian who had insufficient land allotments and who during the war had lost his livestock and the means to cultivate on his own.

From the first, therefore, it was clear to the leaders of the revolution that a change in the system of land tenure must be accompanied by a complete change in the system of husbandry. In the years before the war the average yield of a dessatine of land in Russia was 52 poods for wheat and 61 poods for oats. In Germany the same area of land yielded 137 poods of wheat and 141 poods of oats. The average productive capacity of one Russian rural inhabitant was many times lower than that of an urban inhabitant. The latter numbering four million at the commencement of 1915 produced annually between seven and eight milliard roubles-worth of industrial products, that is, each urban inhabitant produced 3000 roubles-worth each. The 130 million rural workers, on the other hand, produced annually 10 milliard roubles-worth of produce, that is, 125 roubles-worth each. The most intensive production was carried out on the domains of the great estates and from them a large portion of the produce was exported abroad, did not reach the Russian consumer, and the profits on its sale went into the hands of a small aristocratic clique. The young Russian republic of labour, coming into possession of these domains and being faced with the necessity of increasing production, determined to accomplish this end by encouraging the new form of labour commune among the peasantry and half-proletariat. Again the problem of carrying through the agrarian revolution was greatly assisted by the peculiar conditions of Russian society. In the absence of highly-developed farming and of a system of agricultural capitalism, it was not necessary first to break down, as it is in Western and Central Europe, the thousands of private interests, yeomen freeholders and the interests of private land-development syndicates. It was only necessary to remove the effete agrarian aristocracy and then to keep within bounds the anarchical instincts of the less educated peasantry. In this task the leaders of the revolution were assisted by the fact that in Russian society there exists, as I have mentioned above, a numerous element of unskilled workers who have not lost touch with the village and who thus become the link between town and country. This half-peasant half-proletarian became the advanced guard of the revolutionary army educating the backward peasantry in the remote rural districts during the summer of 1918.

But the conditions under which this task was attempted seemed almost hopeless. When the Germans and General Krasnov had cut off the food supplies from the Don and the Ukraine, when the Czecho-Slovaks had cut the great commercial artery of the Volga and the Allies had closed the window to the west at Murmansk, when in fact the economic outlook of Soviet Russia, surrounded by imperialist enemies on every side, seemed blackest, the Central Soviet Executive, nothing daunted, began the work of slowly, laboriously building up the new social order in the villages. I was present in June at a conference of the Central Soviet Executive and the All-Russian Professional Alliances in Moscow just at the darkest hour when all seemed lost. It would have almost seemed better to those, who had not the heart of lions, to confess that the revolution was a failure and to let the proletariat of Russia put back its neck beneath the yoke of the agrarian aristocracy, of ‘financial capital’ and the foreign concessionaires. But the working men of Moscow and Petrograd had indeed the heart of lions. They were already isolated by the governments of the whole world and now at the risk of arousing against them their own peasantry who did not understand the meaning of the agrarian revolution, they decided to create in each rural district ‘committees of the poorer peasantry’, which should stop the more well-to-do elements of the rural population from anarchically breaking up the great estates among themselves and from plundering the domain farms; which should organise the new type of communes and should teach the peasantry in the hard school of discipline that they had responsibilities to the revolution as well as privileges. At first these committees of the poorer peasantry met with resistance in the villages. Rebellions against the republic broke out in many districts and were fermented by the agents of the ‘Allied’ governments and the German government, as the documents published by the Extraordinary Commission for the Fight with the Counter-Revolution proves. Just as the Vendée and the Champagne revolted against the proletariat and the small bourgeoisie of Paris in the French Revolution and were aided by a British naval expedition, which blockaded the French coast in the interests of the ‘real France’, so now the wealthy and ignorant part of the Russian peasantry struck against the urban workers and the half-proletariat and were assisted by the ruling classes of England, who proved true once more to their traditions as suppressors of all movements for freedom in Europe, by conspiring to overthrow the popular movement in Russia. But the peasant revolts in the central provinces were put down by the Soviet Government. Stern revolutionary discipline was enforced and the saying of Mirabeau was confirmed: ‘Angels are not made out of butter in time of revolution.’

What were the Committees of the Poorer Peasantry? They consisted for the most part of that social element referred to above — the half-proletarian, half-peasant class. This class had suffered very severely from the war. Having been employed in unskilled work in towns for part of the year and having had no special qualifications which enabled them to find work in the rear, they were driven by thousands into the Tsar’s army at the crack of the gendarme’s whip. Those who returned found industries requiring only half the number of hands that were employed before, while in the villages the allotments, which they cultivated every spring and summer, had for four years either been left untouched and had gone to waste or else had been taken by someone else, who could not now be ousted. The position of most of them was very tragic, but they readily accepted the idea of forming labour communes to re-establish their ruined husbandry on the land. To this element therefore the revolutionary leaders now turned to organise the ‘committees of the poorer peasantry’. Little by little during the summer of 1918 these committees grew in the western and central provinces. They got their members elected on to the local Soviets, removed speculators and the rich farmer element that had crept into them, took over the administration of the corn requisitioning, and began to establish the new labour communes. This work soon began to bear fruit. By September requisitioned food began to come to the starving towns, and nearly 500 of the new communes were registered with the Commissariat of Agriculture. It was found that a slow but radical improvement in the system of husbandry and in the productivity of the land was beginning. In one place in the Tula province figures were worked out which showed that under the old form of commune 50 persons, cultivating 100 dessatines of land, each working independently of each other, required 40 horses and 12 ploughs. Under the new form of commune, in which each individual worked as a member of the whole, only 20 horses and five ploughs were needed. Thus the saving of time and expense enabled more capital to be laid out in improvements, which in turn increased productivity.

It is possible to go on describing without end the new social perspectives that have opened out before the rural and urban population of Russia as the result of the land and industrial laws passed by the government of the Soviet Republic. All this constructive social work, the greatest and most daring of its kind ever yet attempted in the history of the world, requires to be written not in a pamphlet but in a book — nay, in many books. And, let it be remembered, all this is going on now as I write these lines in spite of the thunder of the revolutionary war, in which the Red Army of the Russian workmen and peasants is defending its labour republic against the attacks upon it from without by the armed forces of the London, Berlin, Paris and New York stock exchanges. But enough has been written to show that what is going on in Russia today is not the work of a mob of madmen or of a gang of robbers. The robbers are they who have been for years under Tsarism sucking the lifeblood of the Russian working class and the peasantry, converting them into slaves to maintain the exploitation profits of syndicates in the ‘City’ and Wall Street. The madmen are they who think that they can, by overthrowing the government of the Soviet Republic through punitive expeditions, re-impose the yoke of financial capital upon the Russian workers and peasants. Madmen, I say, for is it likely, even if these expeditions should succeed, that the Russian people can be permanently reduced to slavery once more? Slavery means that the subjected person must either by superior force or by cajolery be made to obey and work for his master. Can this force be permanently applied to hold down 180 million people? Can they be cajoled to put their necks under the yoke again? The Russian workman and peasant has known for the first time in his history what it is to be a free man and he can say: ‘I am no longer a slave, civis Romanussum.’

Can it be said then that the Russian revolution has brought anarchy and chaos to East Europe? Is it not truer to say that the promoters of anarchy are those governments who in a four years’ holocaust have killed and wounded 25 million human beings, have destroyed thousands of milliards of pounds-worth of the gifts which Nature has given men in order that military castes may have glory and banking cliques may run economic wars after the war and profit out of the blood and tears of their people? Yes, there is the anarchy and chaos — in Western and Central Europe — and it is bringing the rotten house of ‘financial capital’ crashing to the ground. The law and order is seen in the country which, in spite of all the attempts to sow in it anarchy from without, is laboriously building up the new social order in which the workmen are learning to control their own industries and the peasants are learning to work, not as serfs for a seigneur, but as members of a communal society. The leaders of the Bolsheviks who made the October Revolution and inspired the Soviet Government from its outset knew that in making their audacious attempt they had the masses at their back. They found the country floundering in the slough of capitalist chaos and an imperialist war; they liquidated that war and cleared away the agrarian feudalism and the capitalist system, which were automatically burning themselves out in that war; they organised the most conscious and educated element among the working classes in town and country and fought those elements of the peasantry who, not understanding the needs of the moment, went off into anti-social bypaths. Having accomplished this they then laid the foundation of an economic system, transitory between financial capitalism and state socialism. And, whatever happens in the future their work cannot be undone, for conditions are being created in every country of the world which are forcing the masses to liquidate the old social and economic systems. And it is not by a league either of financial capitalists or of so-called ‘democratic’ nations that are run by those capitalists that freedom for humanity can be won. Leagues of that type have already formed in the outer marches of Russia on the Don, in the Ukraine and the Kuban under the combined tutelage of Allied and German military missions, no longer at enmity with one another when once class interests are affected. This is the new form of the Holy Alliance to protect not the legitimacy of sovereigns to rule, as in last century, but the privileges of bankers to profit. The League of Nations can only be a reality when the leaders of the people in Europe and America see what the leaders of the Russian revolution saw in October 1917, that the rebuilding of the whole foundation of human society is the first essential condition to the creation of the palace of the people’s peace. Then there will be a league of nations indeed — a league of free emancipated workers which make up those nations. Then the old order in Europe will be replaced by the new order which, for reasons set forth in the above lines, has appeared first in Russia and is working its way slowly into other lands.

And so to the Russian Revolution we can apply the words of the great French Socialist and philosopher, J Jaurès, in the introduction to his History of the French Revolution:

Let us try to understand the meaning of that fundamental economic evolution which finds its expression in the popular institutions of nations, as well as of that passionate longing of the spirit to reach the eternal truth, that noble uplifting of the individual consciousness which despises suffering, tyranny and death.

These words were written for the French Revolution which liquidated an old social order. They are none the less true today for the Russian Revolution, which in its turn is liquidating the order made possible by the French Revolution. And if we grasp the real meaning of these great movements of mankind that come so rarely and are so terrible for the weak-hearted, but so hopeful for the strong, in the sense suggested to us by Jaurès in his lines, we shall see the Russian Revolution not as the anarchical work of personalities, factions or parties, but as a signpost on the road of Time marking the orderly progress of human society.

Last updated on 10 January 2019