Proponents of the so-called "economic" concept of socially-necessary labor say: a commodity can be sold according to its value only on condition that the general quantity of produced commodities of a given kind corresponds to the volume of social need for those goods or, which is the same thing, that the quantity of labor actually expended in the given branch of industry coincides with the quantity of labor which society can spend on the production of the given type of commodities, supposing a given level of development of productive forces. However, it is obvious that this later quantity of labor depends on the volume of social need for the given products, or on the amount of demand for them. This means that the value of commodities does not only depend on the productivity of labor (which expresses that quantity of labor necessary for the production of commodities under given, average technical conditions), but also on the volume of social needs or demand. Opponents of this conception object that changes in demand which are not accompanied by changes in productivity of labor and in production technique bring about only temporary deviations of market prices from market-values, but not long-run, permanent changes in average prices, i.e., they do not bring about changes in value itself. In order to grasp this problem it is necessary to examine the effect of the mechanism of demand and supply (or competition).[1]

"In the case of supply and demand... the supply is equal to the sum of sellers, or producers, of a certain kind of commodity, and the demand equals the sum of buyers or consumers (both productive and individual) of the same kind of commodity" (C., III, p. 1931). Let us first of all dwell on demand. We must define it more accurately: demand is equal to the sum of buyers multiplied by the average quantity of commodities which each of them buys, i.e., demand equals the sum of commodities which can find buyers on the market. At first glance it seems that the volume of demand is an accurately determined quantity which depends on the volume of social need for a given product. But this is not the case. "The definite social wants are very elastic and changing. Their fixedness is only apparent. If the means of subsistence were cheaper, or money-wages higher, the laborers would buy more of them, and a greater 'social need' would arise for them" (C., III, p. 188; Rubin's italics). As we can see, the volume of demand is determined, not only by the given need of the present day, but also by the size of income or by the buyers' ability to pay, and by the prices of commodities. A peasant population's demand for cotton can be expanded: 1) by the peasant population's greater need for cotton instead of homespun linen (we leave aside the question of the economic or social causes of this change of needs); 2) by an increase of income or purchasing power among the peasants; 3) by a fall in the price of cotton. Assuming a given structure of needs and given purchasing power (i.e., given the distribution of income in the society), the demand for a particular commodity changes in relation to changes in its price. Demand "moves in a direction opposite to prices, swelling when prices fall, and vice versa" (C., III, p. 191). "The expansion or contraction of the market depends on the price of the individual commodity and is inversely proportional to the rise or fall of this price" (Ibid., p. 108). The influence of the indicated cheapening of commodities on the expanding consumption of these commodities will be more intense if this cheapening is not transitory but long-lasting, i.e., if the cheapening is the result of a rise in the productivity of labor in the given branch and of a fall in the value of the product (C., III, p. 657).

Thus the volume of demand for a given commodity changes when the price of the commodity changes. Demand is a quantity which is determined only for a given price of commodities. The dependence of the volume of demand on changes in price has an unequal character for different commodities. Demand for subsistence goods, for example bread, salt, etc., is characterized by low elasticity, i.e., the fluctuations of the volume of consumption of these commodities, and thus of the demand for these commodities, are not as significant as the corresponding price fluctuations. If the price of bread falls to half its former amount, the consumption of bread does not increase two times, but less. This does not mean that the cheapening of bread does not increase the demand for bread. The direct consumption of bread increases to some extent. Furthermore, "a part of the grain may be consumed in the form of brandy or beer; and the increasing consumption of both of these items is by no means confined within narrow limits" (C., III, p. 657). Finally, "price reduction in wheat production may result in making wheat, instead of rye or oats, the principal article of consumption for the masses" (Ibid.), which increases the demand for wheat. Thus even subsistence goods are subsumed by the general law according to which the volume of consumption, and thus the volume of demand for a given commodity, changes inversely to the change in its price. This dependence of demand on price is perfectly obvious if we remember the restricted character of the purchasing power of the masses of population, and in first place of wage laborers in the capitalist society. Only cheap commodities are available to the working masses. Only to the extent that certain commodities become cheaper do they enter the consumption patterns of the majority of the population and become objects of mass demand.

In the capitalist society, social need in general, and also social need equipped with buying power, or the corresponding demand, do not represent, as we have seen, a fixed, precisely-determined magnitude. The magnitude of a particular demand is determined by a given price. If we say that the demand for cloth in a given country during a year is for 240,000 arshins, then we must certainly add: "at a given price," for example 2 roubles 75 kopeks per arshin. Thus demand may be represented on a schedule which shows different quantities of demand in relation to different prices. Let us examine the following demand schedule for cloth:[2]

| PRICES, in roubles (per arshin) |

DEMAND (in arshins) |

| 7 r. - k. | 30,000 |

| 6 r. - k. | 50,000 |

| 5 r. - k. | 75,000 |

| 3 r. 50 k. | 100,000 |

| 3 r. 25 k. | 120,000 |

| 3 r. - k. | 150,000 |

| 2 r. 75 k. | 240,000 |

| 2 r. 50 k. | 300,000 |

| 2 r. - k. | 360,000 |

| 1 r. - k. | 450,000 |

This schedule can be expanded in an upward or a downward direction: upward to the point when commodities will find a small number of buyers from the wealthy classes of society; downward to the point when the need for cloth of the majority of the population is satisfied so fully that a further cheapening of cloth will not cause a further expansion of demand. Between these two extremes, an infinite number of combinations of the volume of demand and the level of prices is possible. Which of these possible combinations takes place in reality? On the basis of the demand alone we cannot see if the volume of demand for 30,000 arshins at 7 roubles per arshin will be realized with a greater probability than a volume of demand for 450,000 arshins at 1 rouble per arshin, or if a combination which lies between these two extremes is more probable. The real volume of demand is determined by the magnitude of the productivity of labor, which is expressed in the value of an arshin of cloth.

Let us turn to the conditions in which the cloth is produced. Let us assume that all cloth factories produce cloth on the basis of the same technical conditions. The productivity of labor in cloth manufacturing is at a level at which it is necessary to expend 2% hours of labor (including expenditures on raw materials, machines, and so on) for the production of 1 arshin of cloth. If we assume that one hour of labor creates a value equal to one rouble, then we get a market-value of 2 roubles 75 kopeks for 1 arshin. In a capitalist economy, the average price of cloth is not equal to the labor-value, but to the production price. In this case, we assume that the production price is equal to 2 roubles 75 kopeks. In our further analysis, we will generally treat market-value as equal either to labor-value or to production price. A market-value of 2 roubles 75 kopeks is a minimum below which the price of cloth cannot fall for long, since such a fall in price would cause a reduction in the production of cloth and a transfer of capital to other branches. We also assume that the value of one arshin of cloth equals 2 roubles 75 kopeks regardless of whether a smaller or a larger quantity of cloth is produced. In other words, the increased production of cloth does not change the quantity of labor or the costs of production spent on the production of one arshin of cloth. In this case the market value of 2 roubles 75 kopeks, "the minimum with which the producers will be content, is also ... the maximum"[3] above which the price cannot rise for long, since such a price increase would cause a transfer of capital from other branches, and an expansion of cloth production. Thus from an infinite quantity of possible combinations of the volume of demand and price, only one combination can exist for long, namely that combination where the market value is equal to the price, i.e., a combination which in Table 1 occupies the seventh place from the top: 2 roubles 75 kopeks-240,000 arshins. Obviously that combination is not manifested exactly, but represents the state of equilibrium, the average level, around which actual market prices and the actual volume of demand will fluctuate. The market value of 2 roubles 75 kopeks determines the volume of effective demand, 240,000 arshins, and the supply (namely the volume of production) will be attracted to this amount. The increase of production, for example, to the level of 300,000 arshins, will bring about, as can be seen in the table, a fall in price below market value, approximately to 2 roubles 50 kopeks, which is disadvantageous for the producers and forces them to decrease production. The inverse will take place in the case of a contraction of production below 240,000 arshins. Normal proportions of production or supply will equal 240,000 arshins. Thus all combinations of our schedule except one can only exist temporarily, expressing an abnormal market situation, and indicating a deviation of market price from market-value. Among all the possible combinations, only the one which corresponds to the market-value: 2 roubles 75 kopeks for 240,000 arshins, represents a state of equilibrium. The market value of 2 roubles 75 kopeks can be called an equilibrium price or normal price, and the amount of production of 240,000 arshins can be called an equilibrium amount[4] which at the same time represent the normal demand and normal supply.

Among the infinity of unstable combinations of demand, we have found only one stable combination of equilibrium which consists of the equilibrium price (value) and its corresponding equilibrium amount. The stability of this combination can be explained in terms of the stability of the production price (value), not by the stability of the equilibrium amount. The mechanism of the capitalist economy does not explain why tne volume of demand tends to be for an amount of 240,000 arshins regardless of all upward and downward fluctuations. But this mechanism does fully explain that market prices must tend toward the value (or production price) of 2 roubles 75 kopeks, in spite of all fluctuations. Thus also the volume of demand tends toward 240,000 arshins. The state of technology determines the value of the product, and value in turn determines the normal volume of demand and the corresponding normal quantity of supply, if we suppose a given level of needs and a given level of income of the population. The deviation of actual from normal supply (i.e., overproduction or underproduction) brings about a deviation of market price from value. This price deviation in turn brings about a tendency to change the actual supply in the direction of normal supply. If this whole system of fluctuations or this mechanism of demand and supply revolves around constant quantities-values-which are determined by the technique of production, then changes of these values which result from the development of productive forces bring about corresponding changes in the entire mechanism of supply and demand. A new center of gravity is created in the market mechanism. Changes in values change the volume of normal demand. If, due to the development of productive forces, the quantity of socially necessary labor needed to produce one arshin of cloth decreased from 2% to 254 hours, and thus the value of one arshin of cloth fell from 2 roubles 75 kopeks to 2 roubles 50 kopeks, then the amount of normal demand and normal supply would be established at the level of 300,000 arshins (if the needs and purchasing power of the population remained unchanged). Changes in value bring about changes in demand and supply. "Hence, if supply and demand regulate the market-price, or rather, the deviations of the market-price from the market-value, then, in turn, the market-value regulates the ratio of supply to demand, or the center round which fluctuations of supply and demand cause market-prices to oscillate" (C., III, p. 181). In other words, value (or normal price) determines normal demand and normal supply. Deviations of actual demand or supply from their normal levels determine "market prices, or more precisely, deviations of market price from market-value," deviations which in turn bring about a movement towards equilibrium. Value regulates price through normal demand and normal supply. We call the equilibrium stage between supply and demand the state in which commodities are sold according to their values. And since the sale of commodities by their values corresponds to the state of equilibrium between different branches of production, we are led to the following conclusion: equilibrium between demand and supply takes place if there is equilibrium between the various branches of production. We would commit a methodological error if we would take the equilibrium between demand and supply as the starting-point for economic analysis. The equilibrium in the distribution of social labor among the different branches of production remains the starting-point, as was the case in our earlier analysis.

Although Marx's views of demand and supply which he expressed in Chapter 10 of Volume III of Capital (and elsewhere) are fragmentary, this does not mean that we do not find in Marx's work indications which testify to the fact that he understood the mechanism of demand and supply in the sense presented above. According to Marx, market-price will correspond to market-value on condition that sellers "bring enough commodities to the market to fill the social requirements, i.e., a quantity for which society is capable of paying the market-value" (Ibid.,). In Marx's words, "social requirements" depend on the quantity of commodities which find buyers on the market at the price which is equal to value, i.e., the quantity which we called "normal demand" or "normal supply." Elsewhere Marx speaks of "the difference between the quantity of the produced commodities and that quantity of them at which they are sold at market-value" (Ibid., p. 186), i.e., of the difference between actual and "normal demand." Thus various passages in Marx's works are explained, passages where he speaks of "usual" social requirements and the "usual" volume of demand and supply. He has in mind "normal demand" and "normal supply," which correspond to a given value and which change if the value changes. Marx said, about an English economist: "The good man does not grasp the fact that it is precisely the change in the cost of production, and thus in the value, which caused a change in the demand, in the present case, and thus in the proportion between demand and supply, and that this change in the demand may bring about a change in the supply. This would prove just the reverse of what our good thinker wants to prove. It would prove that the change in the cost of production is by no means due to the proportion of demand and supply, but rather regulates this proportion" (C., III, p. 191, footnote; Rubin's italics).

We have seen that changes in value (if the requirements and purchasing power of the population are unchanged) bring about changes in the normal volume of demand. Let us now see if there is also an inverse relation here: if a long-range change in demand brings about a change in the value of the product, when the production technique remains unchanged. We are referring to long-range steady changes in demand, and not of temporary changes which only influence market-price. Such long-range changes (for example the increase of demand for a given product) which are independent of changes in the value of products, can take place either because of an increase of purchasing power of the population, or because of increased requirements for a given product. The intensity of needs can increase because of social or natural causes (for example, long-range changes in climactic conditions may create a larger demand for winter clothing). We will treat this question in greater detail below. For now we will accept as given that the schedule of demand for cloth changed, for example, because of increased requirements for winter clothing. Changes in this schedule are expressed by the fact that now a larger number of buyers agree to pay a higher price for cloth, namely that a larger number of buyers and a larger demand correspond to each price of cloth. The schedule takes on the following form:

| PRICES, in roubles (per arshin) |

DEMAND (in arshins) |

| 7 r. - k. | 50,000 |

| 6 r. - k. | 75,000 |

| 5 r. - k. | 100,000 |

| 3 r. 50 k. | 150,000 |

| 3 r. 25 k. | 200,000 |

| 3 r. - k. | 240,000 |

| 2 r. 75 k. | 280,000 |

| 2 r. 50 k. | 320,000 |

| 2 r. - k. | 400,000 |

| 1 r. - k. | 500,000 |

The market-price which corresponded to value in Table 1 was 2 roubles 75 kopeks, and the normal volume of demand and supply was 240,000 arshins. The change in demand shown in Table 2 directly increased the market-price of cloth to about 3 roubles for one arshin, since there were only 240,000 arshins of cloth on the market. According to our schedule, this was the quantity sought by buyers at the price of 3 roubles. All producers sell their commodities, not for 2 roubles 75 kopeks as earlier, but for 3 roubles. Since the production technique did not change (by our assumption), producers received a superprofit of 25 kopeks per arshin. This brings about an expansion of production and, perhaps, even a transfer of capital from other spheres (through expansion of credits which banks give to the cloth industry). Production will expand until it reaches the point when the equilibrium between the cloth industry and other branches of production is reestablished. This takes place when the cloth industry increases its production from 240,000 to 280,000 arshins which will be sold for the previous price of 2 roubles 75 kopeks. This price corresponds to the state of technique and the market-value. The increase or decrease of demand cannot cause a rise or fall in the value of the product if the technical conditions of production do not change, but it may cause an increase or decrease of production in one branch. However, the value of the product is determined exclusively by the level of development of the productive forces and by the technique of production. Consequently, demand does not influence the magnitude of value; rather value, combined with demand which is partly determined by value, determines the volume of production in a given branch, i.e., the distribution of productive forces. "The urgency of needs influences the distribution of productive forces in society, but the relative value of the different products is determined by the labor expended on their production."[5]

If we recognize the influence of changes in demand on the volume of production, on its expansion and contraction, do we contradict the basic concept of Marx's economic theory that the development of the economy is determined by the conditions of production, by the composition and level of development of the productive forces? Not at all. If changes in the demand for a given commodity influence the volume of its production, these changes in demand are in turn brought about by the following causes: 1) changes in the value of a given commodity, for example its cheapening as a result of the development of productive forces in a given productive branch; 2) changes in the purchasing power or the income of different social groups; this means that demand is determined by the income of the different social classes (C., III, pp. 194-5) and "is essentially subject to the mutual relationship of the different classes and their respective economic position" (Ibid., p. 181), which, in turn, changes in relation to the change in productive forces; 3) finally, changes in the intensity or urgency of needs for a given commodity. At first glance it seems that in the last case we make production dependent on consumption. However, we must ask what causes changes in the urgency of needs for a given commodity. We assume that if the price of iron plows and the purchasing power of the population remain the same and the need for plows is increased by the substitution of iron plows for wooden plows in agriculture, the increasing need brings about a temporary increase in the market price of plows above their value, and as a result increases the production of plows. The increased need or demand brings about an expansion of production. However, this increase of demand was brought about by the development of productive forces, not in the given productive branch (in the production of plows) but in other branches (in agriculture). Let us take another example, which is related to consumer goods. Successful anti-alcoholic propaganda decreases the demand for alcoholic beverages; their price temporarily falls below value, and as a result the production of distilleries decreases. We have purposely chosen an example where the reduction of production is brought about by social causes of an ideological and not an economic character. It is obvious that the successes of anti-alcoholic propaganda were brought about by the economic, social, cultural and moral level of different social groups, a level which in turn changes as a result of a complex series of social conditions which surround it. These social conditions can be explained, in the last analysis, by the development of the productive activities of society. Finally, we can move from the economic and social conditions which change demand to natural phenomena which may also influence the volume of demand in some cases. Sharp and long-range changes in climactic conditions could strengthen or weaken the need for winter clothes and bring about an expansion or contraction of cloth production. Here there is no need to mention that changes of demand brought about by purely natural causes and independent of social causes are rare. But even such cases do not contradict the view of the primacy of production over consumption. This view should not be understood in the sense that production is performed automatically, in some kind of vacuum, outside of a society of living people with their various needs which are based on biological requirements (food, protection from cold, etc.). But the objects with which man satisfies his needs and the manner of satisfying these needs are determined by the development of production, and they, in turn, modify the character of the given needs and may even create new needs. "Hunger is hunger; but the hunger that is satisfied with cooked meat eaten with fork and knife is a different kind of hunger from the one that devours raw meat with the aid of hands, nails and teeth."[6] In this particular form hunger is the result of a long historical and social development. In just the same way, changes in climactic conditions bring about needs for given goods, for cloth, namely for cloth of a determined quality and manufacture, i.e., a need whose character is determined by the preceding development of society and, in the last analysis, of its productive forces. The quantitative increase of demand for cloth is different for the different social classes, and depends on their incomes. If in a given period of production, a given level of needs for cloth (a need based on biological requirements) is a fact given in advance or a prerequisite of production, then such a state of needs for cloth is in turn the result of previous social development. "By the very process of production, they [the prerequisites of production] are changed from natural to historical, and if they appear during one period as a natural prerequisite of production, they formed in other periods its historical result" (Ibid., p. 287). The character and change of a requirement for a given product, even if basically a biological requirement, is determined by the development of productive forces which may take place in the given sphere of production or in other spheres; which may take place in the present or in an earlier historical period. Marx does not deny the influence of consumption on production nor the interactions between them (Ibid., p. 292). But his aim is to find social regularity in the changes of needs, a regularity which in the last analysis can be explained in terms of the regularity of the development of productive forces.

We have reached the conclusion that the volume of demand for a given product is determined by the value of the product, and changes when the value changes (if the needs and productive power of the population are given). The development of productive forces in a given branch changes the value of a product and thus the volume of social demand for the product. As can be seen in demand schedule No. 1, a determined volume of demand corresponds to a given value of the product. The volume of demand equals the number of units of the product which are sought at the given price. The multiplication of the value per unit of product (which is determined by the technical conditions of production) times the number of units which will be sold at the given value, expresses the social need which is able to pay for the given product.[7] This is what Marx called the "quantitatively definite social needs" for a given product (C., III, p. 635), the "amount of social want" (Ibid., p. 185), the "given quantity of social want" (Ibid., p. 188). The "definite quantity of social output in the various lines of production" (Ibid.) the "usual extension of reproduction" (Ibid.), correspond to this social need. This usual, normal volume of production is determined by "whether the labor is therefore proportionately distributed among the different spheres in keeping with these social needs, which are quantitatively circumscribed" (C., III, p. 635).

Thus a given magnitude of value per unit of a commodity determines the number of commodities which find buyers, and the product of these two numbers (value times quantity) expresses the volume of social need, by which Marx always understood social need which is able to pay (C., III, pp. 180-181, p. 188, pp. 192-193). If the value of one arshin is 2 roubles 75 kopeks, the number of arshins of cloth which are sought on the market equals 240,000. The volume of social need is expressed by the following quantities: 2 roubles 75 kopeks x 240,000 = 660,000 roubles. If one rouble represents a value created by one hour of labor, then 660,000 hours of average social labor are spent in the production of cloth, given a proportional distribution of labor among the particular branches of production. This amount is not determined in advance by anyone in the capitalist society; no one checks it, and no one is concerned with maintaining it. It is established only as a result of market competition, in a process which is constantly interrupted by deviations and breakdowns, a process in which "chance and caprice have full play" (C., I, p. 355), as Marx pointed out repeatedly (C., I, p. 188). This figure expresses only the average level or the stable center around which the actual volumes of demand and supply fluctuate. The stability of this amount of social need (660,000) is explained exclusively by the fact that it represents a combination or multiplication of two figures, one of which (2 roubles 75 kopeks) is the value per unit of commodity, which is determined by the productive techniques and represents a stable center around which market prices fluctuate. The other figure, 240,000 arshins, depends on the first. The volume of social demand and social production in a given branch fluctuates around the figure 660,000 precisely because market-prices fluctuate around the value of 2 roubles 75 kopeks. The stability of a given volume of social need is the result of the stability of a given magnitude of value as the center of fluctuations of market prices.[8]

Advocates of the "economic" interpretation of socially-necessary labor have placed the entire process on its head, taking its final result, the figure of 660,000 roubles, the value of the entire mass of commodities of a given branch, as the starting-point of their analysis. They say: given a particular level of development of productive forces, society can spend 660,000 hours of labor on cloth production. These hours of labor create a value of 660,000 roubles. The value of the commodities of the given branch must therefore be equal to 660,000 roubles; it can neither be larger nor smaller. This definitely fixed quantity determines the value of a particular unit of a commodity: this figure is equal to the quotient which results from dividing 660,000 by the number of produced units. If 240,000 units of cloth are produced, then the value of one arshin is equal to 2 roubles 75 kopeks; if production increases to 264,000 arshins, then the value falls to 2 roubles 50 kopeks; however, if production falls to 220,000 arshins, then the value rises to 3 roubles. Each of these combinations (2 r. 75 k. x 240,000; 2 r. 50 k. x 264,000; 3 r. x 220,000) equals 660,000. The value of a unit of product can change (2 r. 75 k., 2 r. 50 k., or 3 r.) even if the production technique does not change. The general value of all products (660,000 roubles) has a constant and stable character. The general amount of labor which is needed in a given sphere of production given a proportional distribution of labor (660,000 hours of labor) also has a stable and constant character. In given conditions, this constant magnitude can be combined in different ways with two factors: the value per unit of commodity and the number of manufactured goods (2 r. 75 k. x 240,000 = 2 r. 50 k. x 264,000 = 3 r. x 220,000 = 660,000). In this way, the value of the commodity is not determined by the amount of labor necessary for the production of a unit of commodity, but by the total amount of labor allocated to the given sphere of production[9] divided by the number of manufactured goods.

This summary of the argument of advocates of the so-called "economic" version of socially-necessary labor is, in our view, inadequate for the following reasons:

1) Taking the quantity of labor allocated to a given sphere of production (the result of the complex process of market competition) for the starting-point of analysis, the "economic" version imagines the capitalist society according to the pattern of an organized socialist society in which the proportional distribution of labor is calculated in advance.

2) The interpretation does not examine the question of what determines the quantity of labor which is allocated to a given sphere, a quantity which, in capitalist society, is not determined by anyone nor consciously maintained by anyone. Such analysis would show that the indicated quantity of labor is the result or the product of the value per unit times the quantity of products demanded on the market at a given price. Value is not determined by the quantity of labor in the given sphere, but rather that quantity presupposes value as a magnitude which depends on the production technique.

3) The economic interpretation does not derive the stable, constant (in given conditions) volume of labor which is allocated to a given sphere (660,000 hours of labor) from the stable value per unit of commodity (2 roubles 75 kopeks or 2% hours of labor). Instead, this interpretation derives the stable character of the value of the total mass of products of a given sphere from the multiplication of two different factors (value per unit and quantity). This means that it concludes that the magnitude of value per unit of product (2 roubles 75 kopeks, 2 roubles 50 kopeks, 3 roubles) is unstable and changing. Thus it completely denies the significance of the value per unit of product as the center of gravity of the price fluctuations, and as the basic regulator of the capitalist economy.

4)The economic interpretation does not take into account the fact that among all the possible combinations which yield 660,000 with a given state of technique (and precisely with the expenditure of 2% hours of socially-necessary labor on the production of one arshin of cloth), only one combination is stable: the constant equilibrium combination (namely 2 r. 75 k. x 240,000 = 660,000). However, the other combinations can only be temporary, transitional combinations of disequilibrium. The economic interpretation confuses the state of equilibrium with a state of disturbed equilibrium, value with price.

Two aspects of the economic interpretation must be distinguished: first, this interpretation tries to ascertain certain facts, and secondly, it tries to explain these facts theoretically. It asserts that every change in the volume of production (if technique does not change) brings about an inversely proportional change in the market price of the given product. Due to this inverse proportionality in the changes of both quantities, the product of the multiplication of these two quantities is an unchanged, constant quantity. Thus, if the production of cloth decreases from 240,000 to 220,000 arshins, i.e., by 11/12ths, the price per arshin of cloth increases from 2 r. 75 k to 3 r., i.e., by 12/11ths. The multiplication of the number of commodities by the price per unit in both cases equals 660,000. Going on to explain this, the economic interpretation ascertains that the quantity of labor allocated in a given sphere of production (660,000 hours of labor) is a constant magnitude and determines the sum of values and the market prices of all products of the given sphere. Since this magnitude is constant, the change in the number of goods produced in the given sphere causes inversely proportional changes of value and of the market price per unit of product. The quantity of labor spent in the given sphere of production regulates the value as well as the price per unit of product.

Even if the economic interpretation correctly ascertained the fact that changes in the quantity of products are inversely proportional to changes in the price per unit of product, its theoretical explanation would still be false. The increase of the price of one arshin of cloth from 2 r. 75 k. to 3 r. in the case of a decrease of production from 240,000 to 220,000 arshins would mean a change in the market price of cloth and its deviation from value, which would remain the same if the technical conditions do not change, i.e., it would be equal to 2 r. 75 k. This way, the quantity of labor allocated to a given sphere of production would not be the regulator of the value per unit of product, but would regulate only the market price. The market price of the product at any moment would equal the indicated quantity of labor divided by the number of manufactured goods. This is the way certain spokesmen of the "technical" interpretation represent the problem; they recognize the fact of inverse proportionality between the change in quantity and the market price of a product, but they reject the explanation given by the economic interpretation.[10] There is no doubt that this interpretation, according to which the sum of market prices of products of a given sphere of production represents, despite all price fluctuations, a constant quantity determined by the quantity of labor allocated to the given sphere, is supported by some of Marx's observations.[11] Nevertheless, we think the view of the inverse proportionality between changes in the quantity and the market price of products runs into a whole series of very serious objections:

1) This view contradicts empirical facts which show, for example, that when the number of commodities doubles, the market price does not fall to half the former price, but above or below this price, in different amounts for different products. In this context, a particularly sharp difference can be observed between subsistence goods and luxury goods, According to some calculations, the doubling of the supply of bread lowers its price four or five times.

2) The theoretical conception of the inverse proportionality between the change in the quantity and price of products has not been proved. Why should the price rise from the normal price or value of 2 r. 75 k. to 3 r. (i.e., by 12/11ths of the original price) if production is reduced from 240,000 to 220,000, i.e., by 11/12ths of the previous volume? Is it not possible that (in cloth manufacturing) the price of 3 r. may not correspond to the quantity of production of 220,000 arshins (as the theory of proportionality assumes) but to the quantity of 150,000 arshins, as is shown in our demand schedule No. 1? Where, in capitalist society, is the mechanism which makes the market price of cloth invariably equal to 660,000 roubles?

3) The last question reveals the methodological weakness of the theory we have looked into. In capitalist society, the laws of economic phenomena have similar effects as "the law of gravity" which "asserts itself when a house falls about our ears" (C., I, p. 75), i.e., as tendencies, as centers of fluctuations and of regular deviations. The theory which we are discussing transforms a tendency or a law which regulates events into an empirical fact: the sum of market prices, not only in equilibrium conditions, i.e., as the sum of market values, but in any market situation and at any time, completely coincides with the quantity of labor allocated to the given sphere. The assumption of a "pre-established harmony" is not only disproved, but also does not correspond to the general methodological bases of Marx's theory of the capitalist economy.

The objections we have listed force us to throw out the thesis of the inverse proportionality between changes in the quantity and the market price of products, namely the thesis of the empirical stability of the sum of market prices of the products of a given sphere. Marx's statements in this context must be understood, in our view, not in the sense of an exact inverse proportionality, but in the sense of an inverse direction between changes in the quantity and market price of products. Every increase of production beyond its normal volume brings about a fall in price below value and a decrease of production causes a rise in price. Both of these factors (the quantity of products and their market prices) change in inverse directions, even though not with inverse proportionality. Because of this, the quantity of labor which is allocated to a given sphere does not only play the role of a center of equilibrium, an average level of fluctuation towards which the sum of market prices tends, but represents to some extent a mathematical average of the sums of market prices which change daily. But this character of a mathematical average in no way means that the two quantities completely coincide, and in addition does not have a particular theoretical significance. In Marx's work we generally find a more cautious formulation of the inverse changes in the quantity of products and their market prices (C., III, p. 178; Theorien über den Mehrwert, III, p. 341). We feel all the more justified in interpreting Marx in this sense because in his work we sometimes find a direct negation of the inverse proportionality between changes in the quantity of products and their prices. Marx noted that in the case of a poor crop, "the total price of the diminished supply of grain is greater than the former total price of a larger supply of grain" (Critique, p. 134). This is an expression of the known law which was cited above, according to which the decrease of production of grain to half its former amount raises the price of a pood[12] of grain to more than twice its former price, so that the total sum of prices of grain rises. In another passage, Marx rejects Ramsey's theory, according to which the fall in the value of the product to half its former value due to the improvement of production will be accompanied by an increase of production to twice its former amount: "The value (of commodities) falls, but not in proportion to an increase in their quantity. For example, the quantity may double, but the value of individual commodities may fall from 2 to 1¼, and not to 1" (Theorien über den Mehrwert, III, p. 407), as would follow according to Ramsey and according to proponents of the view we are examining. If the cheapening of commodities (due to an improvement of technique) from 2 r. to WA r. may be accompanied by a doubling of the production of that product, then inversely an abnormal doubling of production may be accompanied by a fall in price from 2 r. to 1¼r., and not to 1 r. as would be required by the thesis of inverse proportionality.

Thus we consider incorrect the view according to which the quantity of labor allocated to a given sphere of production and- to the individual products manufactured in this sphere determines the value of a unit of product (as is held by proponents of the economic interpretation) or coincides precisely with the market price of a unit of product (as is held by proponents of the economic interpretation and some proponents of the technical interpretation). The value per unit of product is determined by the quantity of labor which is socially-necessary for its production. If the level of technique is given, this represents a constant magnitude which does not change in relation to the quantity of manufactured goods. The market price depends on the quantity of goods produced and changes in the opposite direction (but is not inversely proportional) to this change in quantity. However, the market price does not completely coincide with the quotient which results from a division of the quantity of labor allocated to the given sphere with the number of goods produced. Does this mean that we are completely ignoring the quantity of labor which is allocated to a given sphere of production (given a proportional distribution of labor)? In no way. The tendency to a proportional distribution of labor (it would be more accurate to say, a determined, stable[13] distribution of labor) between different spheres of production which depends on the general level of development of productive forces, represents a basic event of economic life which is subject to our examination. But as we have observed more than once, in a capitalist society with its anarchy of production, this tendency does not represent the starting-point of the economic process, but rather its final result. This result is not manifested precisely in empirical facts, but only serves as a center of their fluctuations and deviations. We recognize that the quantity of labor which is allocated to a given sphere of production (given a proportional distribution of labor) plays a certain role as regulator in the capitalist economy, but: 1) this is a regulator in the sense of a tendency, an equilibrium level, a center of fluctuations, and in no way in the sense of an exact expression of empirical events, namely market prices; and 2) which is even more important, this regulator belongs to an entire system of regulators and is a result of the basic regulator of this system-value-as the center of fluctuations of market prices.

Let us take an example with simple figures. Let us assume that: a) the quantity of labor socially necessary to produce one arshin of cloth (given average technique) is equal to 2 hours, or the value of one arshin equals 2 roubles; b) given this value, the quantity of cloth which can be sold on the market, and thus the normal volume of production, consists of 100 arshins of cloth. From this it follows that: c) the quantity of labor required by the given sphere of production is 2 hours x 100 = 200 hours, or the total value of the product of the given sphere equals 2 r. x 100 = 200 roubles. We are facing three regulators or three regulating magnitudes, and each of them is a center of fluctuations of determined, empirical, actual magnitudes. Let us examine the first magnitude: a1) to the extent that it expresses the quantity of labor necessary for the production of one arshin of cloth (two hours of labor), this magnitude influences the actual expenditure of labor in different enterprises of the cloth industry. If a given group of enterprises of low productivity does not spend two but three hours of labor per arshin, it will gradually be forced out by more productive enterprises, unless it adapts to their higher level of technique. If a given group of enterprises does not spend two hours but rather 1½, then this group will gradually force out the more backward enterprises, and in a period of time it will decrease the socially-necessary labor to 1½ hours. In short, the individual and the socially-necessary labor (even though they do not coincide) display a tendency toward equalization. a2) If the same magnitude indicates the value per unit of production (2 roubles), it is the center of the fluctuations of market prices. If market price falls below 2 roubles, production falls and there is a transfer of capital out of the given sphere. If prices rise above values, the opposite takes place. Value and market-price do not coincide, but rather the first is the regulator, the center of fluctuation, of the second.

Let us now move on to the second regulating magnitude, designated by the letter b: the normal volume of production, 100 arshins, is the center of fluctuations of the actual volume of production in the given sphere. If more than 100 arshins are produced, then the price falls below the value of 2 roubles per arshin and a reduction of production begins. The opposite takes place in the case of underproduction. As we can see, the second regulator (b) depends on the first (a2), not only in the sense that the magnitude of value determines the volume of production (given the structure of needs and the purchasing power of the population) but also in the sense that the distortion of the volume of production (overproduction or underproduction) are corrected by the deviation of market prices from value. The normal volume of production, 100 arshins (b), is the center of fluctuations of the actual volume of production precisely because the value of 2 roubles (a2) is the center of fluctuations of market prices.

Finally, we turn to the third regulating magnitude, c, which represents a product of the multiplication of the first two, namely 200 = 2 x 100, or c = ab. However, as we have seen, a can have two meanings: a, represents the quantity of labor expended on the production of one arshin of cloth (2 hours), a2 represents the value of one arshin (2 roubles). If we take a1b = 2 hours of labor x 100 = 200 hours of labor, then we get the quantity of labor which is allocated to a given sphere of production (given proportional distribution of labor), or the center of fluctuations of actual labor expenditures in the given sphere. If we take a2b = 2 roubles x 100 = 200 roubles, then we get the sum of values of the products of the given sphere, or the center of fluctuations of the sums of market values of the products of the given sphere. Thus we do not in any way deny that the third magnitude, c = 200, also plays the role of regulator, of center of fluctuations. However, we derive its role from the regulative role of its components, a and b. As we can see, c = ab, and the regulative role of c is the result of the regulative roles of a and b. 200 hours of labor is the center of fluctuations of the quantity of labor expended in the given sphere precisely because 2 hours of labor indicates the average expenditure of labor per unit of product, and 100 arshins is the center of fluctuations of the volume of production. In just the same way, 200 roubles is the center of fluctuations of the sum of market prices of the given sphere precisely because 2 roubles, or value, is the center of fluctuations of market prices per unit of product, and 100 arshins is the center of fluctuations of the volume of production. All three regulative magnitudes, a, b, and c, represent a unified regulative system in which c is the resultant of a and b, and b, in turn, changes in relation to changes in a. The last magnitude (a), i.e., the quantity of labor socially necessary for the production of a unit of product (2 hours of labor), or the value of a unit of product (2 roubles) is the basic regulating magnitude of the entire system of equilibrium of the capitalist economy.

We have seen that c = ab. This means that c may change in relation to a change in a or to a change in b. This means that the quantity of labor expended in a given sphere diverges from the state of equilibrium (or from a proportional distribution of labor) either because the quantity of labor per unit of production is larger or smaller than what is socially necessary, given the normal quantity of manufactured goods, or because the quantity of units produced is too large or too small compared to the normal quantity of production, given the normal expenditure of labor per unit of production. In the first case 100 arshins are produced, but in technical conditions which may, for example, be below the average level, with an expenditure of three hours of labor per arshin. In the second case, the expenditure of labor per arshin is equal to the normal magnitude, 2 hours of labor, but 150 arshins are produced. In both cases the total expenditure of labor in the given sphere of production consists of 300 hours instead of the normal 200 hours. On this basis, proponents of the economic interpretation consider both cases equal. They assert that overproduction is equivalent to an excessive expenditure of labor per unit of production. This assertion is explained by the fact that all their attention is concentrated exclusively on the derived regulating magnitude c. From this point of view, in both cases there is excessive expenditure of labor in the given sphere: 300 hours of labor instead of 200. But if we do not remain on this derived magnitude, but move on to its components, the basic regulating magnitudes, then the picture changes. In the first case the cause of the divergence lies in the field of a (the expenditure of labor per unit of output), in the second case, in the field of b (the amount of produced goods). In the first case, equilibrium among enterprises with different levels of productivity within a given sphere, breaks down. In the second case, the equilibrium between the quantity of production in the given sphere and in other spheres, i.e., the equilibrium between different spheres of production, breaks down. This is why in the first case equilibrium will be established by the redistribution of productive forces from technically backward enterprises to more productive enterprises within the given sphere; in the second case, the equilibrium will be established by the redistribution of productive forces among different spheres of production. To confuse the two cases would mean to sacrifice the interests of scientific analysis of economic events for a superficial analogy and, as Marx often said, for the sake of "forced abstractions," i.e., the desire to squeeze phenomena of a different economic nature into the same concept of socially-necessary labor.

Thus the basic error of the "economic interpretation" does not lie in the fact that it fails to recognize the regulating role of the quantity of labor which is allocated to a given sphere of production (given a proportional distribution of labor) but in the fact that it: 1) wrongly interprets the role of a regulator in a capitalist economy, transforming it from a level of equilibrium, a center of fluctuations, into a reflection of empirical fact, and 2) it assigns to this regulator an independent and fundamental character, whereas it belongs to an entire system of regulators and actually has a derived character. Value cannot be derived from the quantity of labor allocated to a given sphere, because the quantity of labor changes in relation to changes in value which reflect the development of the productivity of labor. In spite of claims of its proponents, the "economic interpretation" does not complement the "technical" interpretation, but rather discards it: asserting that value changes in relation to the number of produced goods (given constant technique), it rejects the concept of value as a magnitude which depends on the productivity of labor. On the other hand, the "technical interpretation" is able to explain completely the phenomena of the proportional distribution of labor in society and the regulating role of the quantity of labor allocated to a given sphere of production, i.e., to explain those phenomena which the economic interpretation supposedly solved, according to its proponents.

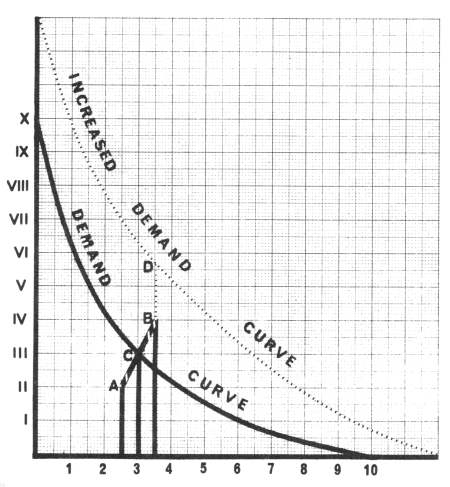

Above, in our schedules of demand and supply, we assumed that the expenditures of labor necessary for the production of a unit of output remained constant when the volume of output increased. Now we introduce a new assumption, namely that a new, additional quantity of products is produced under worse conditions than before. We can remember Ricardo's theory of differential rent. According to this theory, the increase of demand for grain due to the increase in population makes it necessary to farm less fertile land or plots of land which are further away from the market. Thus the quantity of labor necessary for the production of a pood of grain in the least favorable conditions (or for the transportation of grain) increases. And since precisely this quantity of labor determines the value of the entire mass of grain produced, the value of grain rises. The same phenomenon can be observed in mining, when there is a movement from rich mines to less abundant mines. The increase of production is accompanied by an increase in the value per unit of output, whereas earlier we treated the value of a unit of output as independent of the amount of production. An analogous situation can be found in branches of manufacturing where production takes place in enterprises with different levels of productivity. We assume that enterprises with the highest productivity, which could supply goods at the lowest price, cannot produce the quantity of goods which would be demanded on the market at such a low price. In view of the fact that the production must also take place in enterprises of average and low productivity, the market value of commodities is determined by the value of commodities produced in average or less favorable conditions (see the chapter on socially-necessary labor). Here too the increase of production means an increase of value and thus an increase in the price per unit of output. We present the following schedule of supply:

| VOLUME OF PRODUCTION (in arshins) |

PRICE OF PRODUCTION (or value) (in roubles) |

| 100,000 | 2 r. 75 k. |

| 150,000 | 3 r. - k. |

| 200,000 | 3 r. 25 k. |

We assume that if the price level is below 2 r. 75 k., producers will not produce at all and will interrupt production (with the exception, perhaps, of insignificant groups of producers who are not taken into account). To the extent that the price is increased to the level of 3 r. 25 k., production will attract enterprises with average and low productivity. However, a price above 3 r. 25 k. would give such a high profit to entrepreneurs that we can consider the level of production at this price unlimited compared to the limited demand. Thus prices may fluctuate from 2 r. 75 k. to 3 r. 25 k., and the volume of production from 100,000 to 200,000 arshins. However, at what level will the price and the volume of production be established?

We return to demand schedule No. 1 and compare it to the supply schedule. We can see that the price is established at the level of 3 roubles and the volume of production at 150,000 arshins. Equilibrium between demand and supply is established and price coincides with labor-value (or with the price of production), which is determined by the labor expenditures in enterprises of average productivity. Now we assume (as we did above) that, because of this or that cause (because of the increase in the purchasing power of the population or the intensification of the urgency of needs), the demand for cloth increases and is expressed by demand schedule No. 2. The price of 3 roubles cannot be maintained, because at this price the supply consists of 150,000 arshins and the demand of 240,000. The price will rise because of this excess of demand until it reaches the level of 3 r. 25 k. At this price, demand as well as supply equal 200,000 arshins and are in a state of equilibrium. At the same time the new price of 3 r. 25 k. coincides with a new increased value (or price of production) which, due to the expansion of production from 150,000 to 200,000 arshins, is now regulated by the labor expenditures in enterprises with low productivity of labor.

If we said above that the increase in demand influences the volume of production, not influencing the magnitude of value (earlier the increase of production from 240,000 to 280,000 arshins took place at the same value of 2 r. 75 k.), in this case the increase in demand brings about an increase of production from 150,000 to 200,000 arshins, and is accompanied by an increase of value from 3 r. to 3 r. 25 k. Demand somehow determines value.

This conclusion is of decisive significance for representatives of the Anglo-American and mathematical schools in political economy, including Marshall.[14] Some of these economists hold that Ricardo subverted his own theory of labor-value with his theory of differential rent, and that he opened the door for a theory of demand and supply which he rejected, and in the last analysis for a theory which defines the magnitude of value in terms of the magnitude of needs. These economists use the following argument. Value is determined by the labor expenditures on the worse plots of land, or in the least favorable conditions. This means that value increases with the extension of production to worse land or, in general, to less productive enterprises, i.e., to the extent that production increases. And since the increase in production is brought about by an increase in demand, then value does not regulate supply and demand, as Ricardo and Marx thought, but value itself is determined by demand and supply.

Proponents of this argument forget a very important circumstance. In the example we discussed, changes in the volume of production at the same time mean changes in the technical conditions of production in the same branch. Let us examine three examples.

In the first case, production takes place only in better enterprises which supply the market with 100,000 arshins at the price of 2 r. 75 k. In the second case (from which we started in our example), production takes place in the better and average enterprises, which together produce 150,000 arshins at the price of 3 roubles. In the third case, production takes place in the better, average and worse enterprises and reaches a level of 200,000 arshins at the price of 3 r. 25 k. In all three cases, which correspond to our schedule No. 3, not only the volumes of production are different, but also the technical conditions of production in the given branch. The value has changed precisely because the conditions of production changed in the given branch. From this example, we should not draw the conclusion that changes of value are determined by changes in demand and not by changes in technical conditions of production. Inversely, the conclusion can only be that changes in demand cannot influence the magnitude of value in any way except by changing the technical conditions of production in the given branch. Thus the basic proposition of Marx's theory that changes in value are determined exclusively by changes in technical conditions remains valid. Demand cannot influence value directly, but only indirectly, namely by changing the volume of production and thus its technical conditions. Does this indirect influence of demand on value contradict Marx's theory? In no way. Marx's theory defines the causal relationship between changes in value and the development of productive forces. But the development of productive forces, in turn, is subject to the influence of a whole series of social, political and even cultural conditions (for example, the influence of literacy and technical education on the productivity of labor). Has Marxism ever negated that tariff policy or enclosures influence the development of productive forces? These factors may, indirectly even lead to a change in the value of products. The prohibition of imports of cheap foreign raw materials and the necessity to produce them inside the country with large expenditures of labor raises the value of the product processed from these raw materials. Enclosures which pushed peasants to worse and more distant lands led to an increase in the price of grain. Does this mean that changes in value are caused by enclosures or tariff policies and not by changes in the technical conditions of production? On the contrary, from this we conclude that various economic and social conditions, which include changes in demand, may affect value, not side by side with the technical conditions of production, but only through changes in the technical conditions of production. Thus the technique of production remains the only factor which determines value. Marx considered such an indirect effect of demand on value (through changes in the technical conditions of production) entirely possible. In one passage Marx referred to the transfer from better to worse conditions of production which we examined. "In some lines of production it may also bring about a rise in the market-value itself for a shorter or longer period, with a portion of the desired products having to be produced under worse conditions during this period" (C., III, pp. 190-191).[15] On the other hand, the fall of demand can also influence the magnitude of the value of a product. "For instance, if the demand, and consequently the market-price, fall, capital may be withdrawn, thus causing supply to shrink. It may also be that the market-value itself shrinks and balances with the market-price as a result of inventions which reduce the necessary labor-time" (Ibid., p. 190). "In this case, the price of commodities would have changed their value, because of the effect on supply, on the costs of production."[16] it is known that the introduction of new technical methods of production which lower the value of products frequently takes place in conditions of crisis and decreasing sales. No one would say that in these cases the fall in value is due to the fall in demand and not the improvement of the technical conditions of production. And we can hardly say, from the example cited above, that the increase of value is the result of the increase of demand, and not of the worsening of the average technical conditions of production in the given branch.

Let us examine the same question from another angle. Proponents of the theory of demand and supply assert that only competition, or the point of intersection of the demand and supply curves, determines the level of prices. Proponents of the labor theory of value assert that the point of intersection and equilibrium of supply and demand does not change at random, but fluctuates around a given level which is determined by the technical conditions of production. Let us examine this question with the example we have been using.

The demand schedule shows numerous possible combinations of the volume of demand and the price; it does not give us any indication of the combinations which may take place in reality. No combination has greater chances than the others. But as soon as we turn to the supply schedule, we can say with confidence: the technical structure of the given branch of production and the level of productivity of labor in it are limited in advance to the extremities of the value fluctuations between 2 r. 75 k. and 3 r. 25 k. No matter what the volume of demand, the fall of prices below 2 r. 75 k. makes further production disadvantageous and impossible, given the technical conditions. However, a price rise above 3 r. 25 k. causes an immense increase of supply and an opposite movement of prices. This means that only three combinations of supply, determined by the technical conditions of the given branch, confront the infinity of possible demands. The maximum and minimum possible changes of value are established in advance. Our main task in analyzing supply and demand consists of finding "the regulating limits or limiting magnitudes" (C., HI, p. 363).

So far we only know the limits of the changes of value, but we do not yet know if value will equal 2 r. 75 k., 3 r., or 3 r. 25 k. Changes in the volume of production (100,000 arshins, 150,000 arshins or 200,000 arshins) and the extension of production to worse enterprises changes the average magnitude of socially-necessary labor per unit of output, i.e., changes the value (or price of production). These changes are explained by the technical conditions of a given branch.

Among the three possible levels of value, the one that takes place in reality is the level at which the volume of supply equals the volume of demand (in demand schedule No. 1, that value is 3 roubles, and in schedule no 2, 3 r. 25 k.). In both cases the value completely corresponds to the technical conditions of production. In the first case the production of 150,000 arshins takes place in better enterprises. In the second case, in order to produce 200,000 arshins, the worse enterprises must also produce. This increases the average expenditures of socially-necessary labor, and thus the value. Consequently we reach our previous conclusion that demand may indirectly influence only the volume of production. But since a change in the volume of production is equivalent to a change in the average technical conditions of production (given the technical properties of the branch), this leads to the increase of value. In every given case the limits of possible changes of value and the magnitude of value established in reality (obviously as the center of fluctuations of market prices) are completely determined by the technical conditions of production. Without reference to whole series of complicating conditions and round-about methods, our analysis (whose goal is to discover regularities in the seeming chaos of the movement of prices and in competition, in what are at first glance accidental relations of demand and supply) has led us directly to the level of development of productive forces which, in the commodity-capitalist economy, is reflected by the specific social form of value and by changes in the magnitude of value.[17]

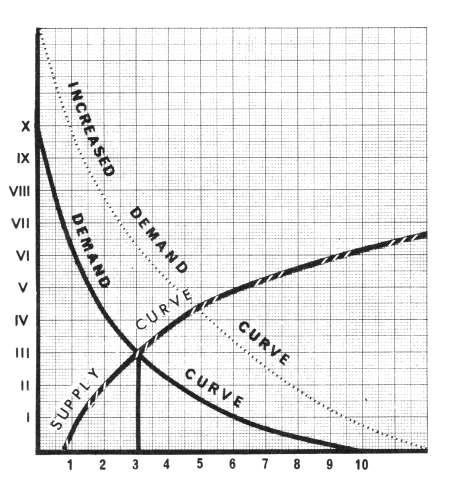

After the preceding analysis, it will not be hard for us to determine value according to the well-known "demand and supply equation" in which the mathematical school formulates its theory of price. This school revives an old theory of supply and demand, eliminating its internal logical contradictions on a new methodological basis. If the earlier theory held that price is determined by the interrelations between demand and supply, the modern mathematical school rigorously understands that the volume of demand and supply depend on price. This way the proposition that there is a causal dependence of price on demand and supply becomes a vicious circle. The labor theory of value emerges from this vicious circle; it recognizes that even if price is determined by supply and demand, the law of value in turn regulates supply. Supply changes in relation to the development of productive forces and to changes in the quantity of socially-necessary labor. The mathematical school has found a different exit from this vicious circle: this school renounced the very question of the causal dependence between the phenomena of price and restricted itself to a mathematical formulation of the functional dependence between price, on the one hand, and the volume of demand and supply, on the other. This theory does not ask why prices change, but only shows how simultaneous changes in price and demand (or supply) take place. The theory illustrates this functional dependence among the phenomena in the following diagram:[18]

The segments along the horizontal axis, 1, 2, 3, etc. ^the horizontal coordinates) show the price per unit of output: 1 rouble, 2 v., 3 r., etc. The segments along the vertical axis (the vertical coordinates) show the quantity of demand or supply, for example, / means 100,000 units, // means 200,000, etc. The demand curve slopes downward; it starts very high at low prices; if the price is near zero, demand is greater than X, i.e. 1,000,000. If the price is 10 roubles demand falls to zero. For every price there is a corresponding volume of demand. To know the volume of demand, for example when the price is 2 roubles, we must extend a vertical line to the point where it cuts the demand curve. The ordinate will be approximately IV i.e., at the price of 2 roubles the demand will be 400,000. The supply curve moves in an inverse sense from the demand curve. It increases if prices increase. The point of intersection of the demand and supply curves determines the price of commodities. If we extend a vertical projection from this point, we see that the point is approximately at 3, i.e., the price equals 3. The amount of the vertical coordinate equals approximately HI, i.e., at the price of 3 roubles the demand and supply equal approximately 300,000, i.e., demand and supply balance each other; they are in equilibrium. This is the equalization of supply and demand which takes place in the given case of a price of 3 roubles. For any other price, equilibirum is impossible. If the price is below 3 roubles, demand will be greater than supply; if the price is above 3 roubles, the supply will exceed the demand.

From the diagram it follows that the price is determined exclusively by the point of intersection of the demand and supply curves. Since this point of intersection moves with every shift of one of the curves, for example the demand curve, then it seems at first glance that the change in demand changes the price, even if there are no changes in the conditions of production. For example, in the case of an increase in demand (the dotted curve of increased demand on the diagram) the demand curve will cross the same supply curve at a different point, a point which corresponds to the quantity 5. This means that in the case of the indicated increase of demand, the equilibrium between demand and supply will take place at a price of 5 roubles. It seems as if the price is not determined by the conditions of production, but exclusively by the demand and supply curves. The change in demand all alone changes the price which is identified with value.

Such a conclusion is the result of an erroneous construction of the supply curve. This curve is constructed according to the pattern of the demand curve, but in the opposite direction, starting with the lowest price. Actually, the mathematical economists grasp the fact that if the price is near zero, there is no supply of goods. This is why they start the supply curve, not at zero, but at a price which approaches 1, on our diagram close to 2/3, i.e., at 66 2/3kopeks. If a price is 66 2/3 then the supply approaches the midpoint towards I, i.e., it is equal to 50,000; if the price is 3 roubles, supply equals 777, i.e., 300,000. At the price of 10 roubles, the curve increases to approximately VI - VII, i.e., it is approximately equal to 650,000 units. Such a supply curve is possible if we are dealing with a market situation at a given moment. If we assume that the normal price is 3 roubles and the normal volume of supply is 300,000, it is possible that if prices fall catastrophically to 66 2/3 kopeks, only a small number of producers will really be forced to sell goods at such a low price, namely 50,000 units at this price. On the other hand, an unusual increase of prices to the level of 10 roubles forces producers to deliver to the market all stocks and inventories and to expand production immediately, if this is possible. It may happen, though it is not very likely, that in this way they will succeed in delivering to the market 650,000 units of goods. But from the accidental price of one day we pass to the permanent, stable, average price which determines the constant, average, normal volume of demand and supply. If we want to find a functional connection between the average level of prices and the average volume of demand and supply on the diagram, we will immediately notice the erroneous construction of the supply curve. If an average volume of supply of 300,000 corresponds to an average price of 3 roubles, then the fall of price to 66 2/3 kopeks, given the previous technique of production, will not result 'in a reduction of average supply to 50,000, but in a total stoppage of supply and a transfer of capital from the given branch to other branches. On the other hand, if the average price (given constant conditions of production) increased from 3 roubles to 10 roubles, this would cause a continuous transfer of capital from other branches, and an increase of the average volume of supply would not remain at 650,000, but would increase far beyond this magnitude. Theoretically, supply would increase until this branch completely devoured all the other branches of production. In practice, the quantity supplied would be larger than any volume of demand, and we could recognize it as an unlimited magnitude. As we can see, some instances of equilibrium between demand and supply, represented in our diagram, unavoidably lead to a destruction of equilibrium among the various branches of production, i.e., to the transfer of productive forces from one branch to another. Since such a transfer changes the volume of supply, this also leads to a destruction of equilibrium between demand and supply. Consequently, the diagram only gives us a picture of a momentary state of the market but does not show us a long-range, stable equilibrium between demand and supply, which may be theoretically understood only as the result of equilibrium between the various branches of production. From the standpoint of equilibrium in the distribution of social labor among the various branches of production, the form of the supply curve must be completely different from that shown in Diagram 1.

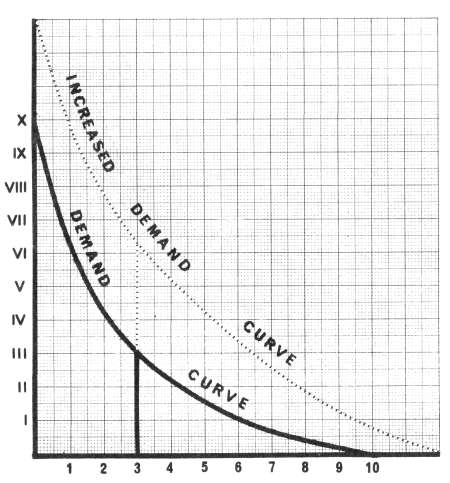

First of all let us assume (as we did at the beginning of this chapter) that the price of production (or value) per unit of output is a given magnitude (for example 3 roubles) independent of the volume of production, if technical conditions are constant. This means that, at the price of 3 roubles, equilibrium is established among the given branches of production and other branches, and the transfer of capital from one branch to another stops. From this it follows that the fall of price below 3 roubles will bring about a transfer of capital from the given sphere and a tendency to a total stoppage of supply of the given commodity. However, the increase of price above 3 roubles will bring about a transfer of capital from other spheres and a tendency to an unlimited increase of production (we may point out that we are, as earlier, not talking of a temporary increase or decrease of price, but of a constant, long-range level of prices, and of an average, long-range volume of supply and demand). Thus if the price is below 3 roubles, supply will stop altogether, and if the price is above 3 roubles, supply may be taken as unlimited in relation to the demand. We do not present any supply curve. The equilibrium between demand and supply can only be established if the level of prices coincides with value (3 roubles). The magnitude of the value (3 roubles) determines the volume of effective demand for a given commodity and the corresponding volume of supply (300,000 units of output). The diagram has the following form:

As we can see from this diagram, the technical conditions of production (or socially-necessary labor in a technical sense) determine value, or the center around which average prices fluctuate (in the capitalist economy such a center will not be labor value, but rather price of production). The vertical coordinate can be established only in relation to the quantity 3, which signifies a value of 3 roubles. However, the demand curve determines only the point which is expressed by the vertical coordinate, namely the volume of effective demand and the volume of production which, in the diagram, approaches the quantity III, i.e., 300,000. A shift of the demand curve, for example an increase of demand for one or another reason, can only increase the volume of supply (in the given example to VI-i.e.. to 600,000-as can be seen from the dotted curve in the diagram) but does not increase the average price which remains, as before, 3 roubles. This price is determined exclusively by the productivity of labor or by the technical conditions of production.

Let us now introduce (as we did earlier) an additional condition. Let us assume that in the given sphere, enterprises of higher productivity can supply to the market only a limited quantity of goods; the rest of the goods have to be produced in enterprises of average and low productivity. If the price of 2 r. 50 k. is the production price (or value) in the better enterprises, the volume of supply will be 200,000 units; if the price is 3 roubles, the supply is 300,000, and at 3 r. 50 k., 400,000. If the average price is below 2 r. 50 k., a tendency to complete stoppage of production will become dominant. If the average price is higher than 3 r. 50 k., a tendency toward unlimited expansion of supply will dominate. Because of this, the fluctuations of average prices are limited in advance by the minimum of 2 r. 50 k. and the maximum of 3 r. 50 k. Three levels of average prices or values are possible within these limits: 2 r. 50 k., 3 r., and 3 r. 50 k. Each of them corresponds to a determined volume of production (200,000, 300,000 and 400,000) and thus to a given level of productive technique. The diagram then has the following form: