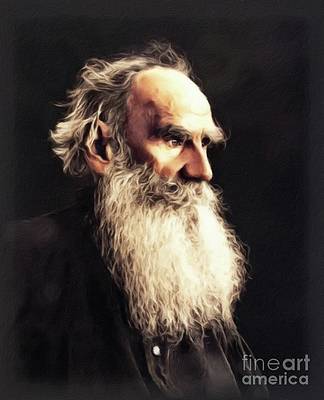

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1868

Source: Original Text from TheAnarchistLibrary.org

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

When Mr. Chevalier returned to his own room, after he had been up-stairs to arrange for his guests, he communicated his observations concerning the newcomers to the partner of his life, who, dressed in laces and silk, had her place in the Paris fashion behind the desk; in the same room sat several of the habitués of the establishment. Serozha, while he was down-stairs, had noticed that room and its occupants. You, probably, have also noticed it if ever you have been in Moscow.

If you, a modest man, not acquainted with Moscow, have arrived too late for a dinner invitation, have been mistaken in your supposition that the hospitable Muscovites will invite you to dinner and they have not invited you, or if you simply desire to dine in the best hotel, you will go into the anteroom. Three or four lackeys will dart forward; one of them will take your shuba from you and congratulate you on the new year, or the carnival, or your return, or will simply remark that it is a long time since you were there, although you may never have been at that establishment in your life. You go in, and the first thing that strikes your eyes is a covered table, spread, as it seems to you at the first instant, with an endless collection of edibles. But this is only an optical delusion, since the larger part of the space on this table is occupied by pheasants in their feathers, indigestible lobsters, baskets with scents, and pomade and vials with cosmetics and comfits. Only if you search carefully you will find vodka and a crust of bread with butter and a piece of fish under a wire fly-screen, perfectly useless in Moscow in the month of December, but there because they are used in that way in Paris.

A little farther on, beyond the table, you will see in front of you the room in which sits the French woman behind the desk, always with a disgusting exterior, and yet with the cleanest of cuffs and in the most charming of modish gowns. Next the Frenchwoman you will see an officer with unbuttoned coat, sipping vodka and reading a newspaper, and a pair of civil or military legs stretched out in a velvet chair, and you will hear a chatter of French and more or less genuine and hearty laughter.

If you wish to find out what is going on in that room, then I should advise you not to go into it, but simply to keep your eyes open as you go by, pretending that you want to obtain a tartine. Otherwise you would be greeted with a questioning silence and with the eyes of the habitués of the room fixed on you, and probably you will put your tail between your legs and take refuge at one of the tables in the big “hall” or in the winter garden. There no one will disturb you. These tables are for the general public, and there in your solitude you may call the garçon and order truffles, as much as you please. This room with the French woman exists for the select gilded youth of Moscow, and to become one of the chosen is not so easy as it may seem to you.

Mr. Chevalier, returning to this room, told his spouse that the man from Siberia was a bore, but on the other hand his son and daughter were young people such as could be brought up only in Siberia.

“You ought to look at the daughter, what a rose she is!”

“Oh, he loves fresh young women—this old man does!” exclaimed one of the guests, who was smoking a cigar.

The conversation, of course, was carried on in French, but I translate it into Russian, as I shall do throughout this story.

“Oh, I am very fond, too, of them,” replied Mr. Chevalier. “Women are my passion. Don’t you believe me?”

“Hear that, Madame Chevalier,” cried a stout young Cossack officer, who was deeply in the debt of the establishment and liked to chat with the landlady.

“Why, you see he shares my taste,” said Chevalier, tapping the stout officer on the epaulet.

“And so the little Sibiryatchka is pretty, is she?”

Chevalier put his fingers together and kissed them.

Whereupon ensued among the occupants a very gay and confidential conversation. It concerned the stout officer; he smiled as he listened to what was said about him.

“Can he have such mutable tastes,” shouted one man through the laughter. “Mademoiselle Clarisse, you know Strugof likes above all things, next to women, hens’ legs.”

Although Mademoiselle Clarisse, from behind her desk, did not see the wit of this remark, she broke out into laughter as silvery as her bad teeth and declining years allowed.

“Has the Siberian girl awakened such thoughts in him?” and again they all laughed harder than ever. Even Mr. Chevalier almost died with laughing, adding, “Ce vieux coquin,” and patting the Cossack officer on the head and shoulders.

“But who are they—these Sibiryaki—manufacturers or merchants?” asked one of the gentlemen when the laughter had somewhat subsided.

“Nikit! Go and ask the gentleman who has just come for his passport,” said Mr. Chevalier. “‘We Alexander, Autocrat.’” ....

Chevalier was just beginning to read the passport which was brought him, when the Cossack officer snatched the paper out of his hands, but his face suddenly expressed amazement.

“Well, now, guess who it is,” said he; “all of you know him by reputation.”

“How can we guess, tell us.” ....

“Well, Abd-el Kader, ha, ha, ha..... Well, Cagliostro, ha, ha, ha..... Well, then, Peter III., ha, ha, ha.”....

“Well, then, read for yourselves.” ....

The Cossack officer unfolded the paper and read: the former Prince Piotr Ivanovitch and one of those Russian names which every one knows and pronounces with a certain respect and pleasure when speaking of any one bearing that name, as of a personal friend or intimate.

We will call it Labazof.

The Cossack officer vaguely remembered that this Piotr Labazof was a person of some consequence in ’25, and that he was sent to the mines of Siberia as a convict, but why he was famous he did not remember very well.

The others knew nothing about it, and they replied:—

“Oh, yes, famous,” just exactly as they would have likewise said “Famous” of Shakespeare who wrote the “Æneid”!

The most that they knew about him was what the stout officer said,—that he was the brother of Prince Ivan, uncle of the Chikins, the Countess Prunk, yes, “famous.” ....

“Why, he must be very rich if he is a brother of Prince Ivan,” remarked one of the young men. “If they have restored his estates to him. They have restored their property to some.”

“How many of these exiles are coming back nowadays,” remarked another person present. “Truly I don’t believe there were so many sent as have already returned. Yes, Zhikinsky, tell us that story about the eighteenth of the month,” said he, addressing an officer of light infantry, reputed as a clever story-teller.

“Yes, tell us it.”

“In the first place, it is genuine truth and happened here, at Chevalier’s, in the large ‘hall.’ Three Dekabrists came here to dinner. They took seats at one table, they ate, they drank, they talked. Now opposite them was sitting a man of respectable appearance, of about the same age, and he kept listening to what they had to say about Siberia:—‘And do you know Nerchinsk?’—‘Why, yes, I lived there.’—‘And do you know Tatyana Ivanovna?’—‘Why, of course I do.’—‘Permit me to ask if you were also exiled?’—‘Yes, I had to suffer that misfortune.’—‘And you?’—‘We were all sent on the 14th of December. Strange that we don’t know you, if you also were among those sent on the 14th. Will you tell us your name?’—‘Feodorof.’—‘Were you also on the 14th?’—‘No, on the 18th.’—‘How on the 18th?’—‘18th of September; for a gold watch; I was falsely charged with stealing it, and though I was innocent, I had to go.’”

All burst out laughing except the narrator, who with a preternaturally solemn face looked at his hearers each and all, and swore that it was a true story.

Shortly after this tale one of the gilded youths got up and went to his club. After passing through the room furnished with tables, where old men were playing cards; after turning into the “infernalnaya” where already the famous “Puchin” was beginning his game against the “assembled crowd”; after lingering awhile near one of the billiard-tables at which a little old man of distinction was making chance shots; and after glancing into the library where some general was reading sedately over his glasses, holding his newspaper far from his eyes, and where a literary young man, striving not to make a noise, was turning over the files of papers,—the gilded youth sat down on a divan in the billiard-room with another man, who like himself belonged to the same gilded youth, and was playing backgammon.

It was the luncheon day, and there were present many gentlemen who were frequenters of the club. Among the number was Ivan Pavlovitch Pakhtin. He was a man of forty, of medium height, pale complexion, stout, with wide shoulders and hips, with a bald head, a shiny, jolly, smooth-shaven face. Though he did not play backgammon, he joined Prince D——, with whom he was on intimate terms, and he did not refuse the glass of champagne which was offered to him. He arranged himself so comfortably after his dinner, slightly smoothing the seat of his trousers, that any one would think he had been sitting there a century, smoking his cigar, sipping his champagne, and happily conscious of the nearness of princes and counts and the sons of ministers. The tidings of the return of the Labazofs disturbed his equanimity. “Where are you going, Pakhtin?” asked the son of a minister, who in the interval of his play, noticed that Pakhtin got up, pulled down his waistcoat, and drank his champagne in great swallows.

“Seviernikof invited me,” said Pakhtin, feeling a certain unsteadiness in his legs, “say, are you going?”

Anastasya, Anastasya, otvoryaï-ka vorota.

This was a gypsy song that was in great vogue at the time.

“Perhaps so. And you?”

“How should I go, an old married man?”

“There now.”

Pakhtin, smiling, went to find Seviernikof in the “glass room.” He liked to have his last word take the form of a jest. And so it was now.

“Tell me, how is the countess’s health?” he asked, as he joined Seviernikof, who did not know him at all, but, as Pakhtin conjectured, would consider it of the greatest importance to know of the Labazofs’ return. Seviernikof had been himself somewhat implicated in the affair of December 14, and was a friend of the Dekabrists.

The countess’s health was much better, and Pakhtin was very glad of it.

“Did you know that Labazof got back to-day, and is staying at Chevalier’s?”

“What is that you say? Why, we are old friends. How glad I am. He has grown old, poor fellow. His wife wrote my wife ....”

But Seviernikof did not cite what she wrote. His partner, who was playing without trumps, made some mistake. While talking with Ivan Pavlovitch, he kept his eye on them, but now suddenly he threw his whole body on the table, and, pounding on it with his hands, proved that he ought to have played a seven.

Ivan Pavlovitch got up and went to another table, joined the conversation there, and communicated to another important man his news, again got up and did the same thing at a third table. All these men of distinction were very glad to hear of Labazof’s return, so that when Ivan Pavlovitch came back to the billiard-room again he no longer doubted, as he had at first, whether it was the proper thing to be glad of Labazof’s return, and no longer employed any periphrasis about the ball, or the article in the Viestnik, or any one’s health, or the weather, but broke his news at once with an enthusiastic account of the happy return of the famous Dekabrist. The little old man, who was still making vain attempts to hit the white ball with his cue, was, in Pakhtin’s opinion, most likely to be rejoiced by the news. He went to him.

“You play remarkably well, your highness,” said Pakhtin, just as the little old man struck his cue full in the marker’s red waistcoat, signifying by this that he wished it chalked.

The title of address[4] was not spoken at all as you would suppose, with any servility,—oh, no, that would have been impossible in 1856. Ivan Pavlovitch called this old man simply by his given name and patronymic, and the title was given partly as a joke on those who did use it, and partly to let it be known that “we know with whom we are speaking, and yet we like to have a bit of sport and that is a fact; “ at any rate, it was very subtile.

“I have just heard that Piotr Labazof has got back. He has arrived to-day from Siberia with his whole family.”

Pakhtin uttered these words at the instant that the little old man was aiming at his ball again—this was his misfortune.

“If he has come back such a hare-brained fellow as he was when he was sent off, there is nothing to be rejoiced over,” said the little old man, gruffly, provoked at his incomprehensible lack of success.

This reply disconcerted Ivan Pavlovitch; once more he did not know whether it was the proper thing to be glad of Labazof’s return, and in order definitely to settle his doubts he directed his steps to the room where the men of intellect collected to talk, the men who knew the significance and object of everything, who knew everything, in one word. Ivan Pavlovitch had the same pleasant relations with the habitués of the “intellectual room” as he had with the gilded youth and the dignitaries. To tell the truth, he was out of his place in the “intellectual room,” but no one was surprised when he entered and sat down on a divan. The talk was turning on the question in what year and on what subject a quarrel had occurred between two Russian journals. Taking advantage of a moment’s silence, Ivan Pavlovitch communicated his tidings, not at all as a matter to rejoice over, nor as a matter of little account, but as if it were connected with the conversation. But immediately, by the way the “intellectuals”—I employ this word to signify the habitués of the “intellectual room”—received the tidings and began to discuss it, immediately Ivan Pavlovitch understood that here at least this tidings was investigated, and that here only it would take such a form as he could safely carry it further, and “savoir à quoi s’en tenir.”

“Labazof was the only one left,” said one of the “intellectuals.” “Now all of the Dekabrists who are alive have returned to Russia.”

“He was one of the band of famous ....” said Pakhtin, in a still experimental tone of voice, ready to make this quotation either comic or serious.

“Undoubtedly Labazof was one of the most important men of that time,” began one of the “intellectuals.” “In 1819 he was ensign of the Semyonovsky regiment and was sent abroad with dispatches for Duke Z——. Then he came back, and in 1824 was admitted to the first Masonic lodge. All the Masons of that time met at D——‘s and at his house. You see, he was very rich; Prince Z——, Feodore D——, Ivan P——, those were his most intimate friends. And so his uncle, Prince Vissarion, in order to remove the young man from their society, brought him to Moscow.”

“Excuse me, Nikolaï Stepanovitch,” interrupted another of the “intellectuals.” “It seems to me that that was in 1823, because Vissarion Labazof was appointed commander of the third Corpus in 1824 and was in Warsaw. He took him on his own staff as aide, and after his dismissal brought him here. However, excuse me, I interrupted you.” ....

“Oh, no, you finish the story.”

“No, I beg of you.”

“No, you finish; you ought to know about it better than I do, and besides, your memory and knowledge have been satisfactorily shown here.”

“Well, in Moscow he resigned, contrary to his uncle’s wishes,” proceeded the one whose “memory and knowledge had been satisfactorily shown.” “And here around him formed another society of which he was the head and heart, if one may so express oneself. He was rich, had a good intellect, was cultivated. They say he was remarkably lovable. My aunt used to say that she never knew a man more charming. And here, just before the conspiracy, he married one of the Krinskys.” ....

“The daughter of Nikolaï Krinsky, the one who before Borodino .... oh, yes, the famous one,” interrupted some one.

“Oh, yes. Her enormous property is his now, but his own estate, which he inherited, went to his younger brother, Prince Ivan, who is now Ober-hoff-kafermeister—that is what he called it—and was minister. Best of all was his behavior toward his brother,” continued the narrator. “When he was arrested the only thing that he had time to destroy was his brother’s letters and papers.”

“Was his brother implicated?”

The narrator did not reply “yes,” but compressed his lips and closed his eyes significantly.

“Then to all questions Piotr Labazof inflexibly denied everything that would reflect on his brother, and for this reason he was punished more severely than the others. But what is best of all is that Prince Ivan got possession of his whole property, and never sent a grosh to him.”

“They say that Piotr Labazof himself renounced it,” remarked one of the listeners.

“Yes, but he renounced it simply because Prince Ivan, just before the coronation, wrote him that if he did not take it they would confiscate the property, and that he had children and obligations, and that now he was not in a condition to restore anything. Piotr replied in two lines: ‘Neither I nor my heirs have or wish to have any claim to the estate assigned to you by law.’ And nothing further. Why should he? And Prince Ivan swallowed it down, and with rapture locked this document and various bonds into his strong-box and showed it to no one.” ....

One of the peculiarities of the “intellectual” room consisted in the fact that its habitués knew, when they wanted to know, everything that was done in the world, however much of a secret it was.

“Nevertheless it is a question,” said a new speaker, “whether it would be fair to take from Prince Ivan’s children the property which they have had ever since they were young, and which they supposed they had a right to.”

The conversation thus took an abstract turn which did not interest Pakhtin.

He felt the necessity of finding fresh persons to communicate his tidings to, and he got up and made his way leisurely through the rooms, stopping here and there to talk. One of his fellow-members delayed him to tell him the news of the Labazofs’ return.

“Who doesn’t know it?” replied Ivan Pavlovitch, smiling calmly as he started for the front door. The news had gone entirely round the circle and was coming back to him again. There was nothing left for him to do at the club, so he went to a reception. It was not a formal reception, but a “salon,” where every evening callers were received. There were present eight ladies and one old colonel, and all of them were awfully bored. Pakhtin’s assurance of bearing and his smiling face had the effect of immediately cheering up the ladies and girls. The tidings was all the more apropos from the fact that there was present the old Countess Fuchs with her daughter. When Pakhtin repeated almost word for word all he had heard in the “intellectual” room, Madame Fuchs, shaking her head and amazed to think how old she was, began to recall how she had once ridden horseback with Natasha Krinsky before she was married to Labazof.

“Her marriage was a very romantic story, and it all took place under my eyes. Natasha was almost engaged to Miatlin, who was afterwards killed in a duel with Debro. Just at that time Prince Piotr came to Moscow, fell in love with her, and made her an offer. Only her father, who was very favorably inclined to Miatlin and was especially afraid of Labazof as a Mason—her father refused his consent. But the young man continued to meet her at balls, everywhere, and he made friends with Miatlin, and asked him to withdraw. Miatlin consented. Labazof persuaded her to elope with him. She had already agreed to do so, but repented at the last moment”—the conversation was carried on in French—“she went to her father and told him that all was ready for their elopement, and that she could leave him, but that she hoped for his generosity. And in fact her father forgave her, all took her part, and he gave his consent. And so the wedding took place, and it was a gay wedding! Who of us dreamed that within a year she would follow him to Siberia? She was an only daughter, the richest and handsomest heiress of that time. The Emperor Alexander always paid her attention at balls, and how many times he danced with her. The Countess G. gave a bal costumé, if I remember rightly; and she went as a Neapolitan girl, wonderfully beautiful. Whenever the Emperor came to Moscow he would ask: Que fait la belle Napolitaine? And suddenly this woman, in a delicate condition,—her baby was born on the way,—without a moment’s hesitation, without making any preparations, without packing her trunks, just as she was, when they arrested him, followed him for five thousand versts.”

“Oh, what a wonderful woman,” exclaimed the hostess.

“And both he and she were such uncommon people,” said still another woman. “I have been told, but I don’t know whether it is true or not, that everywhere in Siberia where they work in the mines, or whatever it is called, the convicts who were with them became better from associating with them.”

“Yes; but she never worked in the mines,” corrected Pakhtin.

That is what the year ’56 was! Three years before no one had a thought for the Labazofs, and if any one remembered them, it was with that inexplicable sense of terror with which one speaks of the recently dead. Now how vividly all their former relations were remembered, all their admirable qualities were brought up, and every lady already began to form plans for securing a monoply of the Labazofs, and by means of them to attract other guests.

“Their son and daughter have come with them,” said Pakhtin.

“If only they are as handsome as their mother was!” said the Countess Fuchs .... however, their father also was very, very handsome.”

“How could they educate their children there?” queried the hostess.

“They say they are admirably educated. They say the young man is so handsome, so likable! and educated as if he had been brought up in Paris.”

“I predict a great success for the young lady,” said a very handsome girl. “All these Siberian ladies have about them something pleasantly trivial, and every one likes it.”

“Yes, that is so,” said another girl.

“So we have still another wealthy match,” said a third girl.

The old colonel, who was of German extraction, and three years before had come to Moscow to make a rich marriage, decided that it was for his interest, as soon as possible, before the young men found out about this, to get an introduction to her, and offer himself. The girls and ladies had almost precisely the same thought regarding the young man from Siberia.

“This must be and is my fate,” thought one girl who for eight years had been vainly launched on society. “It must have been for the best that that stupid cavalier guardsman did not offer himself to me. I should surely have been unhappy.”

“Well, they will all grow yellow with jealousy when this young man like the rest falls in love with me,” thought a young and beautiful woman.

Whatever is said of the provincialism of small towns, there is nothing worse than the provincialism of high society. There one finds no new faces, but society is ready to take up with any new persons as soon as once they appear; here it is rarely that, as now with the Labazofs, people are acknowledged as belonging to their circle and received, and the sensation produced by these new personages was even stronger than would have been the case in a district city.