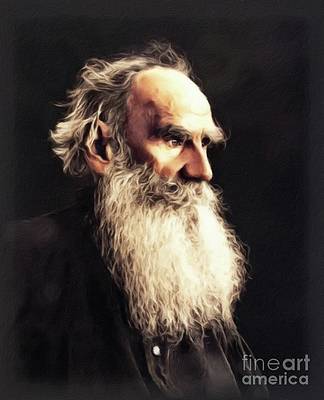

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1887

Source: Original Text from Gutenberg.org

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

The guide pointed out the ford; and the vanguard of cavalry, with the general and his suite immediately in its rear, began to cross the river. The water, which reached the horses' breasts, rushed with extraordinary violence among the white boulders which in some places came to the top, and formed foaming, gurgling whirlpools around the horses' legs. The horses were frightened at the roar of the water, lifted their heads, pricked up their ears, but slowly and carefully picked their way against the stream along the uneven bottom. The riders held up their legs and fire-arms. The foot-soldiers, literally in their shirts alone, lifting above the water their muskets to which were fastened their bundles of clothing, struggled against the force of the stream by clinging together, a score of men at a time, showing noticeable determination on their excited faces. The artillery-men on horseback, with a loud shout, put their horses into the water at full trot. The cannon and green-painted caissons, over which now and then, the water came pouring, plunged with a clang over the rocky bottom; but the noble Cossack horses pulled with united effort, made the water foam, and with dripping tails and manes emerged on the farther shore.

As soon as the crossing was effected, the general's face suddenly took on an expression of deliberation and seriousness; he wheeled his horse around, and at* full gallop rode across the wide forest-surrounded field which spread before us. The Cossack horses were scattered along the edge of the forest.

In the forest appeal's a man in Circassian dress and round cap; then a second and a third ... one of the officers shouts, "Those are Tatars!" At this instant a puff of smoke came from behind a tree ... a report—another. The quick volleys of our men drown out those of the enemy. Only occasionally a bullet, with long-drawn ping like the hum of a bee, flies by, and is the only proof that not all the shots are ours.

Here the infantry at double quick, and with fixed bayonets, dash against the chain; one can hear the heavy reports of the guns, the metallic clash of grape-shot, the whiz of rockets, the crackling of musketry. The cavalry, the infantry, converge from all sides on the wide field. The smoke from the guns, rockets, and fire-arms, unites with the early mist arising from the dew-covered grass.

Colonel Khasánof gallops up to the general, and reins in his horse while at full tilt.

"Your Excellency," says he, lifting his hand to his cap, "give orders for the cavalry to advance. The standards are coming,"[26] and he points with his whip to mounted Tatars, at the head of whom rode two men on white horses with red and blue streamers on their lances.

"All right,[27] Iván Mikháïlovitch," says the general. The colonel wheels his horse round on the spot, draws his saber, and shouts "Hurrah!"

*

"Hurrah! hurrah! hurrah!" echoes from the ranks, and the cavalry dash after him.

All look on with excitement: there is a standard;[28] another; a third; a fourth!...

The enemy, not waiting the assault, fly into the forest, and open a musket fire from behind the trees. The bullets fly more and more thickly.

"Quel charmant coup d'œil!" exclaimed the general as he easily rose in English fashion on his coal-black, slender-limbed little steed.

"Charmant," replies the major, who rolls his r's like a Frenchman, and whipping up his horse dashes after the general. "It's a genuine pleasure to carry on war in such a fine country," says he.[29]

"And above all in good company," adds the general still in French, with a pleasant smile.

The major bowed.

At this time a cannon-ball from the enemy comes flying by with a swift, disagreeable whiz, and strikes something; immediately is heard the groan of a wounded man. This groan impresses me so painfully that the martial picture instantly loses for me all its fascination: but no one beside myself seems to be affected in the same way; the major smiles apparently with the greatest satisfaction; another officer with perfect equanimity repeats the opening words of a speech; the general looks in the opposite direction, and with the most tranquil smile says something in French.

"Will you give orders to reply to their heavy guns?" asks the commander of the artillery, galloping up. "Yes, scare them a little," says the general carelessly, lighting a cigar.

*

The battery is unlimbered, and the cannonade begins. The ground shakes under the report; the firing continues without cessation; and the smoke in which it is scarcely possible to distinguish those attending the guns, blinds the eyes.

The aul is battered down. Again Colonel Khasánof dashes up, and at the general's command darts off to the aul. The war-cry is heard again, and the cavalry disappears in the cloud of its own dust.

The spectacle was truly grandiose. One thing only spoiled the general impression for me as a man who had no part in the affair, and was wholly unwonted to it; and this was that there was too much of it,—the motion and the animation and the shouts. Involuntarily the comparison occurred to me of a man who in his haste would cut the air with a hatchet.

[26] znatchki. This word among the mountaineers has almost the signification of banner, with this single distinction, that each jigit can make a standard for himself and carry it.—AUTHOR'S NOTE.