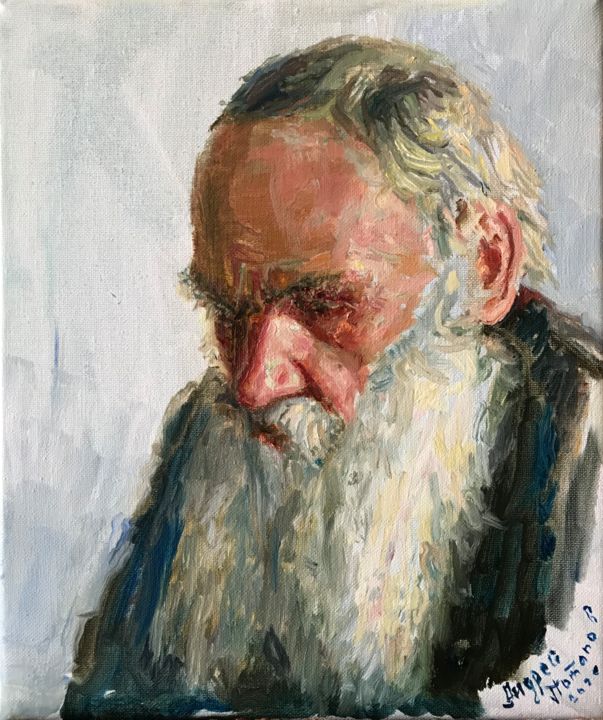

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1904

Source: "Fables for Children," by Leo Tolstoy, translated from the original Russian and edited by leo Wiener, assistant Professor of Slavic Languages at Harvard University, published by Dana Estese Company, Boston, Edition De Luxe, limited to one thousand copies of which this is no. 411, copyright 1904, electrotyped and printed by C. H. Simonds and Co., Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

Man sees with his eyes, hears with his ears, smells with his nose, tastes with his mouth, and feels with his fingers. One man's eyes see better, another man's see worse. One hears from a distance, and another is deaf. One has keen senses and smells a thing from a distance, while another smells at a rotten egg and does not perceive it. One can tell a thing by the touch, and another cannot tell by touch what is wood and what paper. One will take a substance in his mouth and will find it sweet, while another will swallow it without making out whether it is bitter or sweet.

Just so the different senses differ in strength in the animals. But with all the animals the sense of smell is stronger than in man.

When a man wants to recognize a thing, he looks at it, listens to the noise that it makes, now and then smells at it, or tastes it; but, above all, a man has to feel a thing, to recognize it.

But nearly all animals more than anything else need to smell a thing. A horse, a wolf, a dog, a cow, a bear do not know a thing until they smell it.

When a horse is afraid of anything, it snorts,—it clears its nose so as to scent better, and does not stop being afraid until it has smelled the object well.

A dog frequently follows its master's track, but when it sees him, it does not recognize him and begins to bark, until it smells him and finds out that that which has looked so terrible is its master.

Oxen see other oxen stricken down, and hear them roar in the slaughter-house, but still do not understand what is going on. But an ox or a cow need only find a spot where there is ox blood, and smell it, and it will understand and will roar and strike with its feet, and cannot be driven off the spot.

An old man's wife had fallen ill; he went himself to milk the cow. The cow snorted,—she discovered that it was not her mistress, and would not give him any milk. The mistress told her husband to put on her fur coat and kerchief,—and the cow gave milk; but the old man threw open the coat, and the cow scented him, and stopped giving milk.

When hounds follow an animal's trail, they never run on the track itself, but to one side, about twenty paces from it. When an inexperienced hunter wants to show the dog the scent, and sticks its nose on the track, it will always jump to one side. The track itself smells so strong to the dog that it cannot make out on the track whether the animal has run ahead or backward. It runs to one side, and then only discovers in what direction the scent grows stronger, and so follows the animal. The dog does precisely what we do when somebody speaks very loud in our ears; we step a distance away, and only then do we make out what is being said. Or, if anything we are looking at is too close, we step back and only then make it out.

Dogs recognize each other and make signs to each other by means of their scent.

The scent is more delicate still in insects. A bee flies directly to the flower that it wants to reach; a worm crawls to its leaf; a bedbug, a flea, a mosquito scents a man a hundred thousand of its steps away.

If the particles which separate from a substance and enter our noses are small, how small must be those particles that reach the organ of smell of the insects!