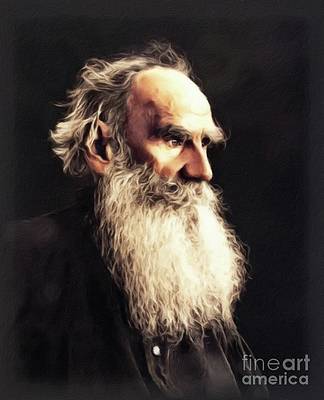

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1908

Source: From RevoltLib.com

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

‘The wretchedness of war and military preparation not only fail to comply with the reasons presented in their justification, but for the most part these reasons are so insignificant that they are unworthy of consideration and are quite unknown to those who die in war.’

‘People are so accustomed to maintaining the external order of life by violence that they cannot conceive of life being possible without violence.

Moreover, if men employ violence to establish an outwardly just life, then the people who establish this sort of life must know what justice is and be just themselves. If some people can know what justice is and are able to be just, why cannot everyone know it and be just?’

‘If people were completely virtuous they would never digress from the truth.

The truth is only dangerous to those who commit evil. Those who do good love the truth.’

‘Reason is often the slave of sin; it strives to justify it.’

‘It is sometimes astonishing to see a person defending very strange, irrational propositions, whether they are religious, political or scientific. Look further and you will discover that he is defending his own position.’

The true meaning of Christ’s teaching consists in the recognition of love as the supreme law of life, and therefore not admitting any exceptions.

Christianity (i.e. the law of love not admitting any exceptions) that does permit the use of violence in the name of other laws, presents an inner contradiction resembling cold fire or hot ice.

It would seem evident that if some people, despite recognizing the virtue of love, can admit the necessity of tormenting or murdering certain people for the sake of some future good, then others, by just the same right and also acknowledging the virtue of love, can claim the same necessity in the name of some future good. Thus it might appear obvious that the admission of any kind of exception to the requirements of fulfilling the law of love diminishes the whole significance, meaning and virtue of this law which lies at the basis of all religious doctrines and teachings on morality. It seems so obvious that one might be ashamed at being asked to prove it; nevertheless the people of Christendom, both believers and nonbelievers who still acknowledge the moral code, regard the teaching on love that opposes all violence (especially the doctrine of nonresistance to evil that follows from the law of love) as something fantastic, impossible and totally inapplicable to life.

One can see why those in power say that without employing violence there can be no order, or decent life, meaning by the word ‘order’, that structure of life wherein the minority can indulge in excess through the labor of others, and by ‘decent life’, the lack of any impediment to leading such a life. However unjust what they say is, one can see that they are able to speak thus because the suppression of violence would not only deprive them of the possibility of living in the way they do, but would expose all the age-old injustice and cruelty of their life.

One might think the working populace do not need the violence which, surprising as it may seem, they employ so systematically against one another, and from which they suffer so badly. For the violence the rulers do to the oppressed is not the direct, spontaneous violence of the strong over the weak, or the majority over the minority, one hundred over twenty, etc. The violence of the rulers is upheld in the only way the violence of the minority over the majority can be: by the fraud which cunning, quick-witted people established long ago, as a consequence of which people, for the sake of small but instant gain, deprive themselves not only of greater profits but of freedom, and expose themselves to the most cruel sufferings. The essence of this fraud was stated as far back as four centuries ago by the French writer La Boëtie in his article ‘Voluntary Slavery’. This is what he says about it:

‘It is not weapons, not armed men – cavalry and infantry – that defend tyrants, but, however hard to believe, three or four men support a tyrant and keep the whole country in servitude to him. The circle of people closest to the tyrant has always consisted of five or six men. These men have either wormed their way into his favor, or been chosen by him, in order to be the accomplices of his cruelty, the companions of his pleasure, and to share in his robberies. These six have six hundred in their power who behave towards the six as the six behave towards the tyrant. The six hundred have six thousand beneath them, whom they have elevated to the position and appointed to govern the provinces and handle financial affairs on the condition they serve their avarice and cruelty. And these are followed by a still larger retinue. And anyone who wishes to get to the heart of the matter will see that there are not just six thousand, but hundreds of thousands, even millions, chained to the tyrant by these links. Thanks to this there is an increase in the number of public functionaries, and this supports the tyranny. And all those who are engaged in this service also profit by it themselves, and by these profits are bound to the tyrant; and the number of people for whom tyranny is advantageous is so plentiful that they approach in number those who would welcome freedom. As the doctor says, if there is something poisonous in our bodies all the bad juices will pour into the unhealthy spot, and it is just the same with governance: as soon as a tyrant is created he gathers all the rotten wastes of the State around him – all the gangs of thieves and good-for-nothings who are unequipped to do anything but are simply self-interested and grasping, assemble in order to participate in the booty, and to become petty tyrants under the chief one.

Thus the tyrant enslaves some of his people through others who, if they were not good-for-nothings, he would fear. But, as they say, ‘in order to chop wood, they take wedges of the same wood’. Similarly, his retainers must be of the same type as those from whom they protect him.

They sometimes suffer at his hands, but these God-forsaken, lost souls are prepared to endure all evil so long as they are in a position to inflict it in their turn – not on those who inflict it on them, but on those who cannot do anything except endure it.’

This lie is now so firmly rooted in the nation that those very people who only suffer from the use of violence justify it and even demand it as if it were something essential to them, and they inflict it on one another. The result of this habit of deception, now become second nature, is the astonishing human delusion whereby the people who suffer the most from the deception are the ones who support it.

One would think it would be the working people, receiving no advantage from the violence exercised over them, who would eventually see through the deceit in which they are entangled and, having once done so, free themselves in the most simple and easy way: by ceasing to participate in the violence which can only be done to them by virtue of their participating in it.

It would seem so simple and natural for the working people, particularly the agricultural workers, who in Russia, as in the rest of the world, form a majority, to finally understand that they have for centuries been suffering from something they have brought upon themselves to no advantage; that the chief cause of their sufferings is that the land is owned by people who do not work on it, and this is upheld by them themselves acting as watchmen, village constables and soldiers; and that all the taxes demanded of them, both directly and indirectly, are collected by them themselves, as village elders, tax-collectors and, again, as policemen and soldiers. It would seem such a simple thing for the working people to realize this and to finally say to those they regard as their leaders: ‘Leave us in peace! If you, emperors, presidents, generals, judges, bishops, professors and other learned men need armies, navies, universities, ballets, synods, conservatoires, prisons, gallows and guillotines, do it all yourselves: collect your own taxes, judge, execute and imprison among yourselves, murder people in war, but do it all yourselves and leave us in peace because we need none of it, and we no longer wish to participate in all these useless, and above all evil deeds!’

What could be more natural than this? And yet, the working people, more especially the agricultural workers for whom none of it is necessary, do not do so, either in Russia or in any other country in the world. Some of them, the majority, continue to torment themselves, fulfilling government demands that run counter to their own needs by becoming policemen, tax collectors or soldiers; while the others, the minority, trying to escape violence, inflict it, at any given revolutionary opportunity, on those from whose violence they suffer; in other words, they stifle fire with fire, and only achieve an increase in the violence used against themselves.

Why do people act so irrationally?

Because, as a result of the perpetuated deception, they can no longer see the connection between their oppression and their participation in violence.

Why do they not see the connection?

For the same reason that accounts for all human misery: because they lack faith and without faith people can only be guided by self-interest, and a person guided only by self-interest cannot do otherwise than deceive or be deceived.

And this leads to the apparently surprising phenomenon that, despite all the evident advantages of violence, despite the fact that the deceit in which the working classes are entangled has become so evident today, despite the obvious exposure of the injustices from which they suffer, despite all the revolutions aimed at the extermination of violence, the working people, the vast majority of the population, not only submit themselves to violence but continue to support it and, contrary to common sense and their own interests, commit acts of violence against each other.

Some of the working people, the vast majority, continue out of habit to cling to the old, false Christian teaching of the Church while no longer believing in it but only in the doctrine of ‘an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth’, and the political structure based on it. The other section, the factory workers who have been touched by civilization (especially in Europe) deny all religion and yet in the depths of their souls they unconsciously believe in the ancient law of ‘an eye for an eye’, and following this they submit, although hating it, to the existing regime when they can see no alternative. When they see an alternative they attempt to exterminate violence through the most diverse violent means.

The first, the great majority of the uncivilized workers, cannot alter their position, because professing belief in the political structure they cannot refrain from participating in violence; the civilized working people, who have no faith and who follow nothing but various political doctrines, cannot free themselves from violence because they try to exterminate it with violence.