Works of Lev Vygotsky

We shall now focus on the concrete material of the studies and try to identify the distinctive traits of the historical development of human behavior. In doing so we shall not consider every single aspect of the behavior of primitive man. We shall merely dwell on the three areas of greatest interest to us, as they will enable us to arrive at certain general conclusions on the history of behavior in general. First we shall consider the memory, and then the thinking and speech of primitive man, as well as his numerical operations, and we shall try to establish how these three functions work.

Let us begin with memory. All observers and travelers have unanimously praised the outstanding memory of primitive man. LÚvy-Bruhl rightly points out that in the psychology and behavior of primitive man memory plays a much greater role than in our mental life, because some of its former functions in our behavior have been transferred elsewhere and changed.

As our experience is condensed in concepts, we are free from the need to retain a huge amount of concrete impressions, whereas in primitive man almost the whole of experience relies on memory. However, besides the quantitative differences between our memory and that of primitive man, it has, as LÚvy-Bruhl has observed, a special tonality which sets it apart from ours.

The constant use of logical mechanisms and abstract concepts has profoundly altered the functioning of our memory. The primitive memory is at once very accurate and very emotional. It retains representations with a great abundance of detail, and always in exactly the same order in which they are really connected to each other. The same author notes that in primitive man the mechanism of memory supplants the mechanism of logic: if one representation reproduces another, the latter is assumed to be a consequence or a conclusion. Signs are therefore almost always interpreted as causes.

LÚvy-Bruhl goes on to remark, “That is why we should expect to find a highly developed memory in primitive man.” He attributes the astonishment of travelers relating the extraordinary powers of the primitive memory to their naive belief that the memory of primitive man has the same functions as our own. It appears to perform miracles, while at the same time functioning quite normally.

Spenser and Gillen found the memory of Australian aboriginals phenomenal in many respects. Not only can they recognize the tracks of each animal and each bird, but they can also immediately tell, by looking at the freshest tracks on the ground, where a particular animal is now. Another remarkable trait is their ability to recognize the footprints of someone they know.

Roth also remarked on the “miraculous powerful memory – of the natives of Queensland. He heard them repeat the whole of a song cycle lasting more than five nights. These songs were reproduced with amazing accuracy. Even more astonishing was the fact that they were performed by tribes speaking different languages, in different dialects and living more than a hundred kilometers apart.

Livingston remarked on the outstanding memory of the natives of Africa, such as that manifested by the envoys of chiefs, who carried very lengthy messages over enormous distances and then repeated them word for word. They usually traveled in groups of two or three, repeating their message each evening as they moved along, so as not to alter its precise language. One of the arguments adduced by the natives against learning to write was that these messengers could transmit news over a long distance quite as well as the written word.

The commonest form of outstanding memory in primitive man is “topographical memory”, or recollection of a particular place. It retains an image of a place, down to the tiniest details, that enables primitive man to find his way with an assurance Europeans regard as astonishing.

As one author says, this kind of memory is practically miraculous. It is sufficient for North American Indians to be in a place just once in order to have a perfectly accurate and permanently indelible picture of it. No matter how vast or dense the forest, they move through it with ease once they have become oriented.

Their sense of direction at sea is just as good. Charlevoix sees in this an innate ability. He wrote, “They are born with this talent, which is the result of neither their observations, nor a large amount of practice. Children who have yet to go beyond the confines of their village move about just as confidently as those who have already travelled throughout the entire country.” [10] Quoting travelers’ tales of extraordinary and seemingly miraculous topographical memory, LÚvy-Bruhl remarks that the only miracle involved is a highly developed local memory. Von dem Steinem describes a primitive man he had observed: he saw and heard everything, accumulating in his memory the most insignificant details, thus making it hard for the author to believe that anyone could memorize so many things without written symbols. He had a map in his head – or rather, he retained in a certain order a huge number of facts, regardless of their relative importance.[11]

As LÚvy-Bruhl points out, primitive man’s exceptionally well developed concrete memory, which so impresses observers with its ability to reproduce previous perceptions in accurate and fine detail, and in the proper order, can also be discerned in the wealth of vocabulary and the grammatical complexity of the language of primitive man.

It is interesting to note that those same people who speak these languages and possess such outstanding memories, in Australia or northern Brazil, for example, cannot count beyond two or three. The slightest abstract reasoning frightens them so much that they promptly say they are tired and give up.

LÚvy-Bruhl had the following to say, “As far as concerns intellectual functions, our own memory is. reduced to the subordinate role of recording the results arrived at through the logical elaboration of concepts. The gap between an eleventh-century scribe who patiently reproduced page after page of a manuscript, and the modern printing press which can print hundreds of thousands of copies in a few hours, is no greater than that which separates the prelogical thinking of primitive man, for whom only the connection between representations exists, and who relies almost exclusively on memory, from logical thought using abstract concepts."[12]

However, such a description of the memory of primitive man, though essentially true, is extremely one-sided. We shall now try to explain, from the scientific standpoint, this. superiority of the primitive memory. At the same time, in order to convey a correct impression of the operation of this memory, we should also note that in a great many respects the memory of primitive man is markedly inferior to that of civilized man.

An Australian child who has never left his village, may impress a civilized European with his ability to find his way around a region where he has never been before. Yet a European schoolchild who has taken just a single geography course will thereby have absorbed more knowledge than primitive man could absorb in a whole lifetime.

Besides the excellent development of the natural memory which records external impressions with virtually photographic precision, primitive memory is also distinguished by the qualitative peculiarity of its functions. This second aspect, when compared with the excellence of the natural memory, sheds some light on the memory of primitive man.

Leroi rightly attributes all the peculiarities of the primitive memory to its functions. Lacking the written word, primitive man has to rely entirely on his immediate memory. This is why we find a similar form of primitive memory in illiterate people. In that same author’s opinion, the explanation for primitive man’s ability to find his way and to reconstruct complex events from tracks, however, lies not in the superiority of the immediate memory, but elsewhere. Most primitive men, as one observer testifies, cannot find their way without some external sign. Leroi assumes that orientation has nothing to do with memory. Similarly, when primitive man reconstructs some event from tracks, he uses his memory no more than when a magistrate investigates a crime on the basis of the evidence. Observation and speculation play a more important role here than memory. Practice has made the sensory organs of primitive man more highly developed than ours – in fact this is all that distinguished him from us in this regard. However, this ability to interpret tracks derives from training and not from instinct. It develops in primitive man from early childhood. Children teach their children to recognize tracks; adults imitate animal tracks, and children reproduce them.

Experimental psychology has quite recently discovered a special and highly interesting form of memory, which many psychologists compare to the astonishing memory of primitive man. Although experimental studies on primitive man in this sphere are being conducted only now, and are still not completed, nonetheless there is such a similarity between the facts collected by psychologists in their laboratories, on the one hand, and those reported about primitive man by researchers and travelers, on the other, that one may safely assume that this form of memory is in fact characteristic of primitive man.

As Pensch has observed, this form of memory essentially enables some humans to actually see an object or picture again, moments after it has been presented to them once, or even a long time thereafter. Such people are known as eidetics, and that form of memory as eidetism. The phenomenon was discovered by Urbanchich in 1907, though experimental studies and research have been conducted on it, by the school of Pensch, only in the past decade.

In the chapter on child psychology, we shall dwell in greater detail on the results of research into eidetism. Here we shall merely discuss the methods, used in such research. For a brief period, of some 10-30 seconds, the eidetic child is shown some highly complex picture with a vast number of details. The picture is then taken away, and is replaced by a gray screen, on which the child continues to see the missing picture in such detail that he can give a thorough description of what is before him, reading the words it contains, etc.

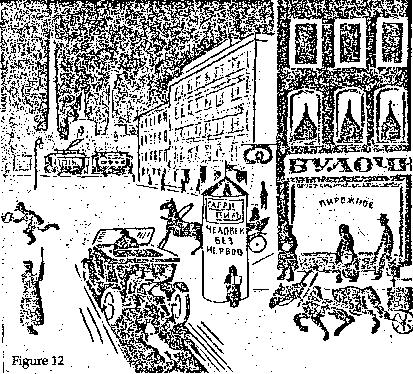

An example illustrating the nature of eidetic memory is given in Figure 12, which is a photo of the picture shown to eidetic children in the experiments of our colleague K.I. Veresotskaya. After being shown the picture briefly (30 seconds) the child continues to see its image on the screen, as verified by control questions and a comparison between the answers and the original of the picture. The child reads the text to the letter, counts up the number of windows on each floor, defines exact arrangement of objects and names their color, describing the tiniest details.

Research has shown that such eidetic images are subject to all – the laws of perception. The physiological basis of such a memory is clearly the inertia of the stimulation of the optical nerve, which lasts after the effect of the original stimulus has ceased. Eidetism of this sort manifests itself not only in vision, but also in auditory and tactile sensations.

Among the civilized peoples, eidetism is found mainly in children. In adults, it is a rare exception. Psychologists believe that eidetism represents an early primitive phase in the development of memory – one that usually ends before puberty and rarely lasts into adulthood. It is found most frequently among mentally retarded and culturally underdeveloped children. Biologically speaking, this form of memory is very important because, as it develops, it turns into two other types of memory. First of all, research has shown that, as develop~ ment progresses, eidetic images merge with our perceptions, rendering them stable and constant. On the other hand, they are transformed into visual images of the memory, in the true sense of the term.

Researchers therefore believe that eidetic memory is a primary undifferentiated stage of the unity of perception and memory, which become differentiated and develop into two separate functions. Eidetic memory is the basis of all graphic, concrete thinking.

The above facts about the outstanding memory of primitive man, collected by LÚvy-Bruhl, lead Pensch to the conclusion that it has much in common with eidetic memory. Moreover, primitive man’s mode of perception, thought and representation is also clearly at a stage of development remarkably close to the eidetic stage. Pensch likened the visionaries found among primitive peoples to two eidetic boys he once studied, who sometimes saw the most extraordinary places and buildings.

Bearing in mind that visual images can be strengthened in eidetics by emotional stimulus or exercise as well as by various pharmacological substances, it seems that the famous pharmacologist Levin was right to assert that the shamans, or medicine men, of primitive peoples artificially induce eidetic activity in themselves. Mythological creativity on the part of primitive man is also close to the seeing of visions and eidetism.

Comparing all these facts with those of eidetic research, Pensch concludes that our knowledge of the memory of primitive man suggests that it is in the eidetic phase of memory development. Mythological images, in his opinion, are also due to eidetism.

Blonsky observes that, “We need only add that such elves and goblins, coming into being in the right circumstances and under the influence of powerful emotions among primitive eidetics, are then reinforced by the longlasting state of mind characteristic of eidetics. Eidetism among the primitive peoples accounts not only for the emergence of mythological images, but also of certain peculiarities of primitive language and art.

With its abundance of concrete details and words, the language of primitive man, which we shall discuss below, is far more colorful and graphic than the languages of civilized peoples. With regard to art, Wundt raised the question of why, of all places, the graphic art of cave-dwellers flourished in the dark interior of caves. Blonsky believed that this was “because eidetic images are. brighter in the dark, or when one’s eye is closed.”

Dantsel has reached similar conclusions on this question, arguing that memory plays an immeasurably greater role in the mental life of primitive man than in our own. A remarkable feature of the operation of this type of memory is the “unprocessed nature of the materials” retained by the memory, and its persistently photographic quality. The reproductive function of such a memory is far higher than in civilized man.

As Dantsel has observed, aside from its fidelity and objectivity, primitive memory is also astonishingly well integrated. The memory of primitive man does not move incrementally from one element to the next, since his memory retains the entire phenomenon for him as a whole, and not parts of it.

The last distinctive trait of the memory of primitive man, in the opinion of Dantsel, is that primitive man still finds it very difficult to separate perceptions from recollections. In his mind, those objective things that he has actually perceived merge with what he has merely imagined. The only explanation for this can the eidetic nature of the recollections of primitive man.[13]

The organic memory of primitive man, or the so-called mnema, based on the plasticity of our nervous system – its ability to retain and reproduce the imprint of external stimuli – reaches its most highly developed state in primitive man. Beyond that, no further development is possible.

As primitive man gradually absorbs culture, we find this type of memory declining, just as it does during the cultural development of the child. The question then arises: which path does the development of the memory of primitive man follow? Does the memory we have just described become improved in the shift from a low to a higher level?

Research has invariably shown that this does not happen in actual fact. Here we hasten to emphasize the distinctive form memory takes in this case, a form which is extremely significant in the historical development of behavior. As an objective scrutiny of primitive man will show, it functions spontaneously, like a natural force.

In the words of Engels that we have quoted earlier, man uses it but does not dominate it. Indeed, this type of memory dominates him, by suggesting to him unreal fictions, and imaginary images and constructions. It leads him to establish mythologies that often impede the development of his experience, by screening the objective picture of the world behind subjective structures.

The historical development of memory begins from the point at which man first shifts from using memory, as a natural force, to dominating it. This dominion, like any dominion over a natural force, simply means that at a certain stage of his development man accumulates sufficient experience – in this case .psychological experience – and sufficient knowledge of the laws governing the operation of memory, and then shifts to the actual use of those laws. This process of accumulation of psychological experience leading to control of behavior should not be viewed as a process of conscious experience, the deliberate accumulation of knowledge and theoretical research. This experience should be called “naive psychology” by analogy with what K÷hler calls “naive physics”, with reference to the naive experience of apes with regard to the physical properties of their own bodies and of objects in the external world.

There comes a stage of his development in which primitive man first graduates from the ability to interpret tracks as signs suggesting and recalling entire complex pictures, in other words, from the use of signs to the creation of artificial signs. This truly marks a turning point in the history of the development of the memory of primitive man.

Thurnwald describes a primitive man in his service who used to take “auxiliary memory tools” with him when sent to the main camp with instructions, precisely in order to remember them. Despite the case made by Dantsel, Thurnwald believes that the use of auxiliary means need not be viewed from the standpoint of their magical origins. In its earliest form, writing acted precisely as such an auxiliary, by means of which man began to dominate his memory.

Writing has a long history. The original tools of memory were symbols, such as the golden figurines of West African storytellers, each which of brings to mind a special tale. Each of these figurines is a kind of initial title of a long story, for example the moon. A bag containing such figurines represents the primitive title of such early storytellers.

Other symbols are of an abstract character. As Thurnwald has observed, one typical abstract symbol of this sort is the knot, tied as a reminder of something, just the way we do today. He further noted that as these tools of memory are used in an identical fashion within certain groups, they become convention and begin to serve for purposes of communication.

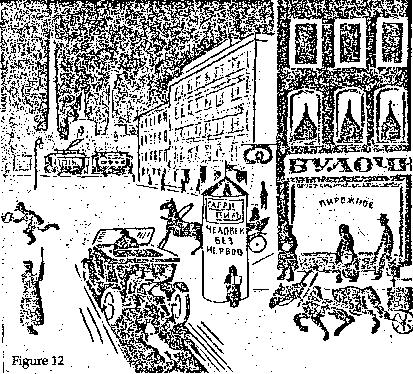

In Figure 13 we see a sample of the writing of primitive man. It consists of stringy reed fiber, two pieces of reed, four shells and a piece of fruit skin. There is a letter from an incurably ill father to his friends and relatives, saying that his illness is worsening and that help can come only from God.

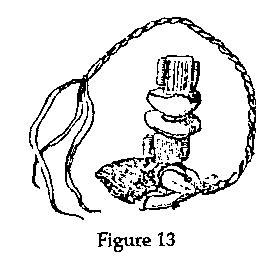

Among the Indians of the Dakota tribe such signs have acquired a general meaning. In Figure 14, the hole in feather (a), means that its bearer has killed his enemy; the triangular indentation in feather (b) means that he has slit his enemy’s throat and scalped him; the truncated end of feather (c) means that he has slit his throat; and the split feather (d) means that he has wounded his enemy.

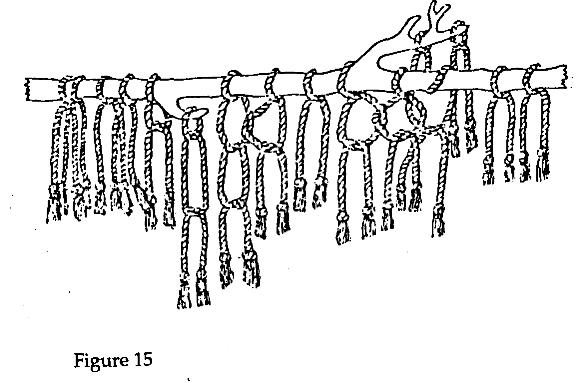

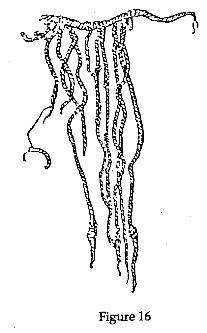

The most ancient monuments in the history of writing are the kvinus (“knots” in Peruvian) shown in Figures 15 and 16, which were used in ancient Peru, China, Japan and other parts of the world. These are conventional auxiliary signs for the memory which are in widespread use among the primitive peoples and require precise knowledge on the part of those tying the knots.

Such kvinus are still used today in Bolivia by herdsmen as a means of counting their livestock; they are also found in Tibet and elsewhere. The system within which the signs and the counting methods is used are closely linked to the economic way of life of these primitive peoples. Not only the knots but also the colors of the string have their own significance. White strings means silver and peace; red, warriors or war; green, corn; and yellow, gold.

Klodd considers the mnemonic stage to be the first stage in the development of writing. According to Herodotus, when Darius ordered the lonians to stay behind to defend a pontoon bridge across the river Ister Danube, he tied sixty knots on a strap, saying, “People of lonia, take this strap and do as I say. As soon as you see that I have attacked the Scythians, from then on you must untie one knot on each succeeding day, and when you find that the days marked by these knots have passed, then you may go home.”

This kind of knot, tied as a memory aid, is clearly the oldest vestige of man’s shift from the use of memory to control over it.

These kvinus were used in ancient Peru for recording the chronicles, for the transmission of instructions to remote provinces and detailed information about the state of the army. They were even placed inside tombs to preserve the memory of the deceased.

The Chudi tribe of Peru, according to Taylor, had a special officer assigned to the task of tying and interpreting kvinus. Although they became highly proficient at their craft, they were rarely able to read other people’s kvinus, unless they were accompanied by oral comment. Anyone arriving from a remote province with a kvinu had to explain whether it was in connection with a census, the collection of taxes, war, etc.

Through constant practice the officials improved their system to such an extent that they could use these knots to record all the major matters of state, and depict laws and events. Taylor reports that in southern Peru there are still some Indians who are thoroughly familiar with the contents of several historical kvinus that have been preserved since ancient times, but that they keep their knowledge a closely guarded secret, and are particularly anxious to hide it from whites.

Nowadays, this kind of knot-based mnemotechnical system is most frequently used for the memorization of various counting operations. Peruvian herdsmen record their bulls on one string of the kvinu, their cows, subdivided into milking and dry, on the second, and then their calves, sheep, etc. The products of animal husbandry are recorded by means of knots tied on special strings. The color of the string and the different ways the knots are tied indicate the nature of the record being kept.

Instead of dwelling on the further development of human writing, we shall simply say that this transition from the natural development of memory to the development of writing – from eidetism to the use of external systems of signs, from mnema to mnemotechics – was an absolutely pivotal change, which determined the entire subsequent course of the development of human memory. Internal development had now become external.

Memory is enhanced to the extent that systems of writing and of symbols, together with the methods for using those symbols, are enhanced. This corresponds to what was known in ancient and medieval times as memoria technica, or artificial memory. The historical development of human memory essentially consists of the development and enhancement of the auxiliary means elaborated by social man in the process of his cultural life.

At the same time, however, while the natural or organic memory obviously does not remain unchanged the changes that do occur are determined by two vital factors. Firstly, those changes are not autonomous. The memory of a man capable of recording what he needs to remember is used and exercised, and therefore develops, differently from the memory of a man who is quite incapable of using symbols. The internal development and enhancement of memory is accordingly not an autonomous process; it is dependent and subordinate, since its course is determined by external influences within man’s social environment.

A second and equally important limitation is the highly one-sided nature of the development and enhancement of this kind of memory. Since it adapts to the type of writing system prevalent in any given society, in many respects it does not develop at all. Instead, degeneration and involution occur; in other words, it loses its properties, or undergoes retrograde development.

In this way, for example, during the process of cultural development the outstanding natural memory of primitive man tends to wither away. Baldwin was therefore quite right to uphold the idea that all evolution is to an equal extent involution; in other words, retrograde processes, whereby old forms shrink and wither away are themselves inherent in any process of development.

We need only compare the memory of an African envoy, transmitting word for word the lengthy message of some tribal chief, relying solely on his natural eidetic memory, with the memory of a Peruvian “officer in charge of knots”, Who had to tie and read the kvinu, to see the direction in which human memory developed under the influence of the growth of culture. In particular, such a comparison shows us the driving force behind such development, and the precise manner in which it occurred.

The “officer in charge of knots” stands higher on the ladder of cultural development than the African ambassador, not because of a commensurate improvement in his natural memory, but because he has learned to make better use of memory, and to dominate it by means of artificial signs.

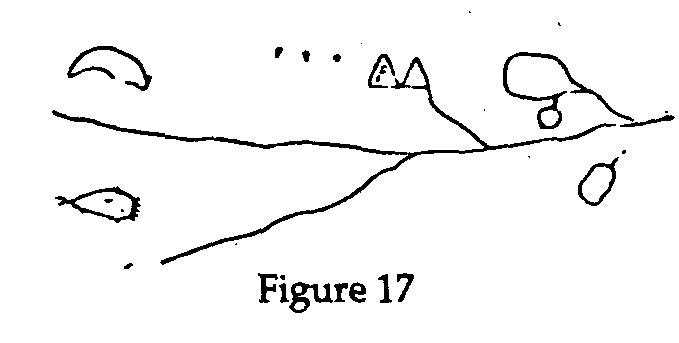

We shall now go one step higher and consider the kind of memory corresponding to the next stage in the development of writing. Figure 17 gives an example of what is known as “pictographic” writing, in which visual images serve to convey certain thoughts and concepts. On a piece of birch bark, a girl from the Ojibwa tribe is writing a letter to her lover in white territory. Her totem is a bear, and his, an ant chrysalis. These symbols refer to the sender and the recipient of the letter. Two lines from the site of these symbols, converge and then continue as far as a place lying between two lakes. A path leading to two tents branches off from this line. Three girls who are converts to the Catholic faith – as indicated by three crosses – live here in their tents. The tent on the left is open, and a hand making a beckoning gesture is protruding from it. The hand, which belongs to the author of the letter, is making the Indian sign of welcome to her lover – with the palm held forward and pointed down – while the extended index finger points to the place occupied by the speaker, showing her guest the path to be followed.

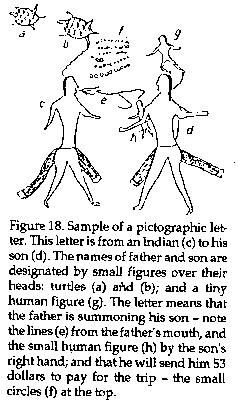

Writing at this stage already requires the memory to function in a completely different manner (see Figure 18). Yet another form enters the picture when man moves on to ideographic or hieroglyphic writing, using symbols whose relationship with objects becomes increasingly remote. Mallory has rightly observed that in most cases these were merely mnemonic inscriptions, but that they were interpreted in connection with physical objects used for mnemonic purposes.[14]

The remarkable story of writing, of man’s efforts to control his memory, is uniquely characteristic of human psychology. The decisive point in the transition from natural to cultural development of memory lies in the watershed dividing mnema from mnemotechnics, the use of memory from dominion over it, the biological or internal form of its development from the historical or external form.

We should note that such dominion over memory first took the form of signs intended less for oneself than for others, with social purposes, which only later came also to have a personal use. Arsenyev, noted for his research on. the Ussur region, describes a visit to an Udekheitsy village, in an extremely remote location. The Udekheitsy complained of encroachments by the Chinese, and asked him, on his return to Vladivostok, to convey their feelings to the Russian authorities and seek their help.

When the traveler left the next day, a crowd of its inhabitants escorted him to the outskirts of the village. A gray-haired elder stepped out of the crowd, handed him a lynx claw and instructed him to put it in his pocket, so as not to forget their request concerning Li-Tai-Kui. Not trusting their natural memory, the Udekheitsy used an artificial symbol, totally unrelated to the things the traveler had to remember, which was an auxiliary technical tool of memory, a way of steering memorization into the proper channel and controlling its flow.

The operation of memorization with the aid of a lynx claw, addressed first to another and then to oneself, marks the beginning of the path followed by the development of memory in civilized man. Everything that civilized humanity remembers and knows at present, all the accumulated experience in books, monuments and manuscripts – all this colossal expansion of the human memory, without which there could be no historical and cultural development, Is due precisely to external human memorization based on symbols.