Fr

France—1793

This year marked the beginning of the second period of the French Revolution; this was characterized by the dictatorship of the petty bourgeoisie supported by the working masses of the capital. Having been removed from the throne Louis XVI became the centre of all the counter.revolutionary movements in the country: he bribed members of the legislative assembly, made contact with the European monarchs and prepared a military campaign against the revolutionary country. Robespierre and Marat, the leaders of the left wing of the Jacobin coalition correctly estimated the role of the king in the formation of a European coalition against revolutionary France. ‘Before we assault the foreign tyrants we must finish with our own tyrant as Robespierre said or as Marat said ‘Before we can deal with the kings outside France let us finish with the king of France’. On January 21 the king was executed. On February 1, Britain joined the European coalition. The revolutionary army which had up to that time sustained victories, lost one conquered territory after another. The Convention which was controlled by the Girondists sent out commissars into the departments to recruit three hundred thousand men. On Danton’s suggestion the Convention established on March 10 an extraordinary criminal tribunal for infringements of the ‘freedom, equality and sovereignty of the people.’ Famine ravaged the country, recruiting levies ruined the peasantry and a counter.revolutionary mutiny flared up in the Vendée. In the Convention a struggle developed between the Montagne and the Gironde. Whether all feudal obligations should be abolished without compensation and whether a law on a maximum, i.e. a tax on bread and on other prime necessities, be introduced—upon the solution of these two problems hung the fate of the two revolutionary classes the peasantry and the urban petty-bourgeoisie. The commune of Paris resolved to exact from the rich a special levy of twelve million livres for military needs.

The Convention set up the Committee of Twelve to investigate the action of the commune. On May 31. the commune declared an insurrection The Montagne put 29 Girondist deputies on trial. On July 13, Charlotte Corday murdered Marat. On July 27, Danton, a representative of the bourgeois intelligentsia who had attempted to reconcile the Girondists and the Montagnards was removed from power. Robespierre became the head of the govern. ment. The Reign of Terror struck down the enemies of the revolu. tion. On October 31 the arrested Girondists were executed. The Convention adopted the draft of a new constitution introducing universal suffrage, abolishing all feudal obligations without com. pensation, returning common lands to the peasants and issued a law on maxima, and progressive income tax and a whole number of other measures of a social-economic nature. 1793 formed the culminating year in the development of the revolution. From then on the revolution began its decline.

See French Revolution Archive.

France—1830

1830—The period 1815-1830 in France was characterized by the rapid development of capitalism and a corresponding growth of the industrial bourgeoisie. However, only the very largest industrialists and financiers were drawn into the management of the state apparatus whose power belonged to the noblemen and the big bourgeois landowners. In their interest, high duties on corn were introduced which increased the price of bread and were thus unfavourable to the industrial bourgeoisie. The aristocratic reaction strengthened their positions increasingly; the government decided to award a thousand million francs to emigrants for the lands they had lost, abolish Jury courts and to expel oppositionists from the civil service. The liberals formed the political representatives of the bourgeoisie and together with the deputies of other opposition groups held in parliament 270 votes out of 430. But then by the decree of July 26, the king dissolved parliament. The July revolution of 1830 was the answer to this. For three days on end the workers of Paris fought on the barricades while the soldiers refused to go into action against the people. The liberal bourgeoisie took fright at the revolution. Its leader, Thiers, later to be the butcher of this Paris Commune, addressed an appeal to the people in which he proposed to hand the crown to a nominee of the French people. The result of the July revolution was the substitution of one king by another and the transfer of power from the big landowners to the financial bourgeoisie. ‘From now on the bankers will reign’ said the liberal banker Laffitte as he escorted the new king Louis-Philippe Orleans into the Hotel de Ville. ‘Laffite gave away the secret of the revolution’ as Marx put it.

France—1848

1848—Although in this period France saw the growing antagonism of two classes, the proletariat and the bourgeoisie, for their struggle against a common enemy, the ruling finance clique, they entered into a temporary agreement in order to liquidate the July monarchy. Two world economic events hastened the revolutionary eruption of 1848 – the potato blight and poor harvest of 1845 and 1846 and the general commercial and industrial crisis in Britain. In Paris during the winter of 1847, assistance had to be given to more than a third of the city’s population. A series of banquets formed the starting-point of the movement in which at first even the most moderate bourgeois groups took part. They demanded the relaxation of the electoral qualifications. The republicans joined with the moderate bourgeoisie, the so-called dynastic left. After the government’s banning of the banquet to be held in the 12th arrondissement the movement overflowed on to the streets. The business initiated by the bourgeoisie was completed by the revolutionary movement of the working masses. On February 24, after a three-day battle on the barricades, the monarchy was overthrown. A provisional government was formed in which two representatives of the workers sat: Louis Blanc and Albert (Alexandre Martin). Under the pressure of the Paris proletariat the provisional government proclaimed a republic in the government of which the workers’ representatives put forward the demand ‘the organization of labour and the creation of a special ministry of labour’. A proletarian ministry of labour existing alongside bourgeois ministries of finance, trade, and public works, could not in effect be other than a bourgeois ministry of labour and inevitably was to turn into a ‘ministry of impotence, a ministry of good intentions and a socialist synagogue’. The Paris proletariat did force the republic to make this concession to it. National workshops were organized which by the end of May employed over 100,000 workers and paid out daily in wages some 70,000 livres. However, the ‘right to work’ could not solve the basic problems facing the country. The financial question was solved by the government by introducing a new tax of 45 centimes on each peasant holding – this set the peasants against the revolution. A second question was that of the date of convening the Constituent Assembly. The bourgeoisie wanted to convene the Assembly as soon as possible. The republicans and socialists sought to postpone the elections to the Assembly so as to have an opportunity to organize the revolution and to educate the masses and win their confidence in revolutionary power. They managed to get it postponed from April 9 to the 23. When it met, a majority of members of the Constituent Assembly consisted of moderate republicans while from the workers representatives only Louis Blanc and Albert gained seats. The elections marked the victory of the bourgeoisie over the prole-tariat and of the towns over the countryside. Feeling its new power, the government of the bourgeoisie on May 24 made an order for the closing down of the national workshops and the moving of the workers employed in them from Paris. On June 21, the order began to take effect. The result was the June uprising which was drowned in the blood of the Paris workers. Some 50,000 were killed and some 25,000 arrested. On June 28, the uprising was crushed and on the 30th the annulment of the decree limiting the length of the working day was announced. Reaction had triumphed. On December 10, 1848 elections for the president of the republic were declared.

Louis Napoleon Bonaparte was elected receiving 54 million votes of 74 million. Marx wrote: ‘December 10, 1848 was the day of the peasant insurrection ... The republic had announced itself to this class as the tax collector; this class announced itself to the republic with the emperor.’ On December 2, 1851 the president of the republic dissolved the legislative National Assembly and proclaimed himself emperor. Louis-Napoleon reigned until 1871.

See Revolution of 1848 History Archive.

France—1871

1871—This refers to the Paris Commune which held power from March 18 until May 28, 1871. The basic causes leading to the proclamation of the Commune were the catastrophic defeat of France in the Franco-German War, the openly displayed treachery and impotence of the reactionary Thiers government and the grave famine facing the working masses of Paris who had expected from the government the collection and requisitioning of supplies and other measures in vain. The Commune was remarkable for its radical legislation which found an expression in the acts of abolish-ing the standing army, the separation of church from state and so forth. A socialist character was borne by the decrees on the registration of factories abandoned by their owners and the plans for their operation and the equalization of the pay of all state officials with that of workers’ wages. However capitalism did not die away under the Commune but concealed its power substantially intact. The Communards fatally hesitated to seize the Bank of France. Generally the working class was insufficiently conscious and organized and after a heroic eight-day resistance the Paris Commune fell to the forces of the Thiers government. The triumphant bourgeoisie took savage reprisals against the insurgent workers. The Paris Commune played a role of world-historical importance. It was an embodiment of the dictatorship of the proletariat in an incomplete form. The Paris Commune destroyed the illusion of a peaceful transfer of power to the proletariat. The Communards under-estimated the furious resistance that the ruling classes would mount. Besides this the Commune brought home the necessity for the centralized leadership of a political party without which even the most powerful spontaneous movement can be easily smashed. Herein lie the principal lessons of the Paris Commune. For a more detailed analysis the reader should see Marx’s The Civil War in France and Lenin’s The State and Revolution.

See Paris Commune History Archive.

Franco-Prussian War (July 19, 1870 - May 10, 1871)

This war marked the end of French hegemony in Europe and resulted in the creation of Germany as Europe's strongest economic and military power. The war brought to an end an era of military tactics: close troop formations and cavalry charges, seriously under assault since the US Revolutionary war, disappeared from Europe after the war.

Background: In May 1869, Empress Eugenie of France, seeing the gradual rot and decay of the Empire, declared that the spoils of war would save the Bonaparte dynasty; namely the expansion of the French border to the Rhine river. Meanwhile, Prussia had recently defeated Austria in the Seven Weeks war in 1866, and was a rising power in Europe. By September 1869, an agreement of the growing Prussian threat was reached between Austria, Italy and France; all three realized that should Prussia ever unite with the Southern German states, the balance of power in Europe could be in Prussian hands, with Napolean III explaining: "I can guarantee peace only as long as Bismarck respects the present status: if he draws the south German states into the North German Confederation, our guns will go off by themselves."

On July 2nd 1870, the Provisional Spanish Government proclaimed the candidature of Prince Leopold of the Hohenzollern dynasty (whose staunchest supporter was Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck) as the next King of Spain, succeeding Queen Isabella who had been deposed in September 1868. Not only was the Prince Prussian, but he was of Southern German decent and a Catholic -- the prospects of which were dreadful for France. On July 6th, France protested, and on July 9th, the French Ambassador to Prussia, Count Vincent Benedetti, requested Kaiser William I to withdrawal the candidacy while the Kaiser was on vacation at Bad Ems. On July 12th, Leopold recieved and obeyed his Kaiser's instructions to step down and withdrawal his candidacy.

The French wanted a greater diplomatic route, and on the next day sent Ambassador Benedetti to request that Kaiser William I promise that never again would a Prussian Prince aspire to the Spanish throne. While the Kaiser was polite and diplomatic in his refusal, Bismarck seized the moment and published the world over an inflammatory note in the hopes of instigating a war in his infamous Ems Dispatch. On July 19th, an outraged Napolean III of France in response declared war on Prussia.

Military Preparedness: The French army was an accomplished force; re-organised in 1866 to meet with the changing times, they possesed two powerful technological innovations: the whole army was equipped with the breech-loading chassepot rifle; and some units were equipped with the gas powered gattling gun. Previous gatling guns could work only with hand cranks; but with the introduction of smokeless powder, gatling guns became internally powered. Since smokeless powder burns at an even rate, gasses emitted from the explosion of the round are directed to a piston which rotates the weapon to the next barrel. Without an even rate of burn the gun would jam or misfire, since an equal amount of power is needed to turn to the next barrell -- any more or less would not turn the weapon sufficiently or would turn it too much.

The Prussian military, however, was not without its own innovations and power. The bolt-action rifle was invented by a Prussian (Dreyse in 1838), and was used for the first time in the war of 1866 with enourmous success. The Prussian soldiers ripped through Austrian armies, firing six shots for every one fired by the Austrians. All of Europe realized the awesome power of the bolt action as a result, and began producing them in masse. The French version was created by Antoine-Alphonse Chassepot; an 11 millimetre rifle called the Fusil d'Infanterie Modéle 1866, of which 1.03 million were ready at the outset of the war. The Prussian rifle featured a much bigger round and a faster rate of fire in the 15.43 millimetre Zundnadelgewehr Modell 1862, and being equipped with 1.15 million rifles, Prussian troops were experienced with the pros and cons of using such a deadly weapon. After the war, both rifles would be upgraded considerably due to the low quality and reliability of paper cartridges (a legacy from the musket area), the paper would be replaced by a metal encasment holding the round and powder.

Furthermore, in what would remain an area of great success and national pride until the end of the second world war, Prussia had another tremendous advantage; the theories of Clausewitz (which would be translated into English after the war) and the genius of General Hulmuth von Moltke. The Prussian military created an exteremly capable and effecient Army general staff under the direction of General Moltke as chief of staff, who planned to excrucating detail the rapid and highly organised depolyment of massive troop formations to the various battle fronts. Molke's brilliance was in creating a decentralized command structure to achieve greater centralization of forces on the battlefield: "An order shall contain everything that a commander cannot do by himself, but nothing else." Instead of concentrating troop movements, Moltke believed in seperating columns while moving into position and co-ordinating attacks at various points, instead of launching one massive push. No nation in the world compared to Prussia's awesome ability, nor gave the same degree of resources and importance, to managing war in a synergy of decentralization and potency.

Bismark thus had extreme confidence in the capabilities of his military, and believed that a sucessful war against the thereto all-powerful France would be cause enough to end centuries of infighting among the divided states of Germany. Bismark envisioned a united nation of Germany, with Prussia and its North German Confederation at the helm. At the outset of war, Bismark saw immediate results: the South German states of Bavaria, Baden, and Wurttemberg agreed to send troops to "defend" Prussia as a result of France's declaration of war. This gave Prussia a large numercial superiority over the French, but the Prussians were even more prepared for war than all of Europe could imagine.

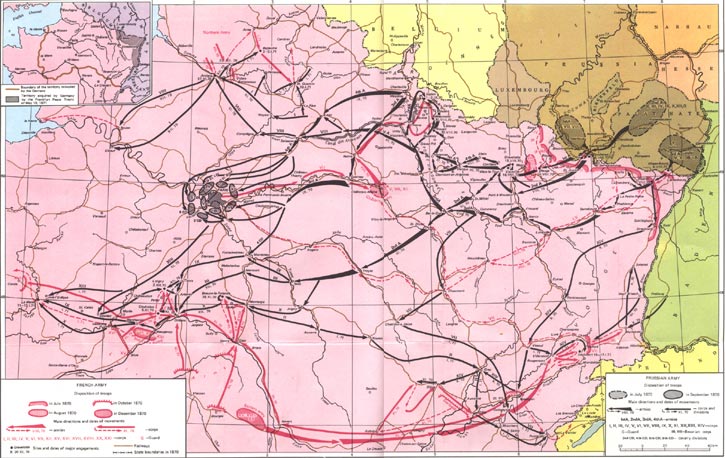

War: Soldiers of the North German Confederation and the South German States mobilised and achieved full strategic deployment on the Trier-Landau line in 13 days. Less than five days later 380,000 Prussian troops were on France's Eastern border. France was bewildered and in disarray. Though they had declared the war, their historcial laurels of arrogance had not thoroughly prepared for it, and they were astonished to see the armies of those they declared war on marching straight for France's cities!

As the Prussian's massed huge amounts of soldiers at the front, French soldiers scurried to thier posts late and without proper supplies. The Prussians devoloped a Northern (1st and 2nd Army) and Southern (3rd Army) spearhead; to which the French responded by creating a front 180 km long, from Strasbourg to Sierck. On August 4th, the Prussian 3rd Army attacked the Southern line, and immediately won the border city of Wissenberg from the French; quickly moving onto capture the city of Woerth two days later.

The French held the strong position of Fröschweiler and the heights near it [just outside of Woerth] with the utmost tenacity and conspicuous bravery.... Little by little we gained ground as the battle progressed. The unceasing din of cannon and musketry re-echoed loudly in the hills, while the sun had now broken through the clouds. Already numerous convoys of prisoners were passing the spot where I stood... A sight I shall never forget was that of a rifleman shot through the mouth, who was carried by on a stretcher directly under my eyes, and kept briskly waving his hand to me as long as ever he could see me, as he was unable to speak.... I could clearly recognize that little by little the French right wing was being retired--a movement the enemy carried out with exemplary skill, while his left wing held its ground against the Bavarians with the utmost tenacity. Several times over I saw French advances pushed forward with the greatest impetuosity, in which Zouaves leapt about with incredible agility; yet our gallant fellows repelled every attack successfully.... [After a successful push by the Bavarians] The French then were actually on the run; they were beaten and we were the victors! MacMahon's tough resistance, his practical skill, fighting for a gradual withdrawal, were well worthy of admiration - but he relinquished the battle-field to me and I had vanquished him.

War Diary of the Emperor Frederick III (Son of Kaiser William I), Sulz 6 August, 1870.

After less than a week of fighting, the entire French Rhine Army's Southern line (the I and V French Corps commanded by Marshal Patrice MacMahon) couldn't withstand the Prussian aggression and retreated West, further into French territory. The Prussians were relentless. On the same day of the French Southern retreat, 65 km to the North, the French Northern line (II, III and IV Corps, under Marshal Achille Bazaine) were beaten by the Prussians led by General Helmuth von Moltke near Saarbrucken, and retreated to the fortress at Metz, marking the begining of the most important battles of the war. By August 14th, the Prussian 1st Army, bitting at the heals of the retreating French, captured the city of Pange, about 15km East of Metz. Meanwhile, the Prussian 2nd Army split from the 1st in a flanking maneavour around Metz, meeting little resistance on the way, and captured the city of Pont´ Mousson and then Vionville on August 16th -- a city 20 km West of Metz.

Battles of Mars la Tour and Gravelotte: 130,000 French soldiers were bottled up in the Fortress of Metz after suffering several defeats at the front. Shortly four days after their retreat, on the 16th, the ever-present Prussian forces, here a group of grossly outnumbered 30,000 men of the advanced III Corps (of the 2nd Army) under General Constantine von Alvensleben, found the French Army near Vionville, east of Mars-la-Tour. Despite odds of four to one, the heroic III Corps routed the French and captured Vionville, blocking any further escape attempts to the West. Once blocked from retreat, the French in the fortress of Metz had no choice but to fight in a battle that would see the last majory calvary engagement in Western Europe. III corps was decimated by the incesent calvary changes, losing over half its soldiers, while the French suffered equivelent numerical loses of 16,000 soldiers, but still held onto overwhelming numercial superiortiy. The following day, on the 17th, the French ran for the hills between Saint-Privat-la-Montagne and Gravelotte, a few kilometers to the west of Metz, not realizing the Prussians had outflanked them. The French secured an extremely defensible position in the hills, and naturally, the Prussians attacked regardless.

The Prussians invaded St. Privat in the northern tip of the French forces, and suffered huge loses in bloody door to door fighting at the hands of fierce French soldiers and citizens. Meanwhile, in the Southern section of the line near Gravelotte, where French soldiers had dug themselves into trenches behind a deep ravine, the Prussian soliders (VII and VIII Corps, led by Moltke) were absolutely slaughtered and almost totally annihalted in an insane assault attempt, losing over 20,000 men (compared to 13,000 French). When night fell on August 18th, however, the French general's had eyes only for defeat, and instead of seizing a perfect opportunity to counter-attack, Bazaine ordered his valliant troops to pull back to Metz under the cloak of night. The seige of Metz was thus underway.

Battle of Sedan: Meanwhile, 60 km to the South, the Prussian 3rd Army was capturing town after town, while thier defeated opponents of the French Rhine Army (I and V Corps) hastily retreated to Chalon-s.-Marne making sure to stay out of the way of the advancing Prussians by heading Southwest while the Prussians drove West.

The 120,000 strong remnants of the French Rhine army (I, VII, XII Corps), was now led by both Mac-Mahon and Napoleon III. The French began marching from Chalons-s.-Marne North/Northeast, in an attempt to rally the besieged army at Metz over 130 km to the East (leaving V and VI Corps behind to protect Chalons-s.Marne, which the Prussians would never end up attacking). But the Prussian 3rd Army advance was incredible; in less than 3 weeks the army covered over 325 km, and intercepted the French army along the Meuse River, and for three days battled it (August 29 to 31), forcing the French to fall to Sedan. Meanwhile, the Prussians had created a 4th Army from the IV and XII Corps of the 2nd Army, and marched the 4th to the Southern flank of Sedan, while the 3rd Army dug in North of Sedan.

On September 1, 1870, the Prussians thus layed siege to the city of Sedan. Standing at the gates was a powerful force of 200,000 Prussian soldiers under the prolific General Helmuth von Moltke. The French were highly indecisive, allowing the Germans to move in re-inforcements to completely encircle Sedan. The French would then counter the encirclement with bloody but largely ineffective cavalry charges. The Prussians were not merely content to lay seige with Napolean III captive behind city walls, however, and thus launched a massive offensive on September 2nd. Napolean quickly surrendered, along with his remaining 83,000 French troops. The Prussians then began thier march on Paris.

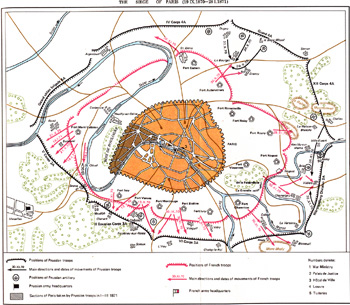

The Seige of Paris: In France, a new goverment arose in Paris on September 4th, 1870, and declared the establishment of the Third Republic. But by September 19, the Prussians began to besiege Paris. French citizens and soldiers began fighting the Prussians in a guerilla war, achieving much better results than they had as a conventional army commanded by weak leadership. The couragous Léon Gambetta escaped Paris in a baloon, and began organising a new convential army in the countryside. After learning that Bismark would settle for nothing less than Alsace and Lorraine, Jules Favre, foreign minister in the Government for National Defence, broke off peace negotiations. But the French army was without hope, and its leadership decimated; the fortress at Metz finally fell on October 27th, after Bazaine surrendered along with his 140,000 soldiers. On 27th December 1870, on Bismarck's orders and against the advice of the Empress and General Moltke, Paris was bombarded. Paris endured several months of hardship while making many attempts to break the seige, but finally gave in as well, on January 28, 1871.

Treaty of Frankfurt: The fall of Paris was allowed by the French leaders so long as a French National Assembly could be elected with the authority to conclude a definite peace. Adolphe Thiers and Favre came to consensus on this agreement after lengthy deliberations on February 26, and it was ratified on March 1. This gave cause for the rise to the Paris Commune, which overthrew the power of the French burecrats in Paris and aimed at liberating all of France for the working people themselves. The Commune was betrayed by the same cowardly French generals who fled the battle fields months earlier, Generals who commanded French brothers to set thier sights on thier fellow workers to appease their new Prussian lords and the desperate French aristocracy. After tens of thousands of citizens of Paris were slaughtered and shot without trial in a vicous blood bath ordered by the French aristocrats, Prussia enacted the terms of its treaty on May 10, 1871: Prussia annexed Alsace, Moselle, Haut Rhine, Bas Rhine, and half of Lorraine; in addition France had to pay an indemnity of 5 billion francs. Until the reparations were paid, the Prussians would continue to occupy France and charge France for all costs associated with the continued occupation.

The victory of Prussia brought about the union of Germany under Prussian hegemony. Wilhelm I was crowned Emperor of Germany at Versailles on 18th January 1871.

[Speaking on the next great war Germany would wage:] "Its length will be incalculable and its end nowhere in sight... and woe to him who first sets fire to Europe, who first puts the flame to the powderkeg!"

Helmuth Karl von Moltke, 1890

By the outbreak of World War I, every nation in Europe had rebuilt thier armies around the tactics and principles envisioned by Moltke, but none would use it so effectively as his German inheritors for decades to come.

Prussian battle statistics for August 4 to January 28:

156 "significant small actions"

17 major battles

26 fortresses captured

11,650 French Officers captured

363,000 French Soldiers captured

Battle dates redux:

August: 13 actions, 8 battles at Wissembourg (4th), Wörth (6th), Spicheren (6th), Courcelles, Vionville, Gravelotte (18th), Noisseville, Beaumont-Sedan; 4 fortress were taken- Lützelstein, Lichtenberg, Marsal, Vitry.

September: 13 actions, Sedan (1st); 4 fortresses were taken: Sedan, Lyon, Toul (23rd), Strasbourg.

October: 37 actions; 3 fortresses were taken: Soissons (15th), Schlettstadt, Metz.

November: 15 actions, 2 battles at Amiens and Beaune-la-Rolande; 7 fortresses were taken: Verdun, Montbéliard, Neuf-Brisach, Ham, Thionville, La Fčre (27th), the Citadel of Amiens.

December: 30 actions, the battles around Orleans and on the Hallue; 2 fortresses were taken: Pfalzburg, Montmédy.

January: 48 actions, 3 battles at Le Mans, Montbéliard, and St.Quentin (19th); 5 fortresses were taken: Mézières, Rocroy, Péronne, Longwy, Paris.

The new German Empire:

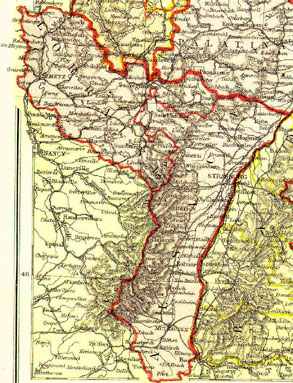

The newly annexed territory of Alsace and Lorrane (map of 1882):

See Notes on the Franco-Prussian War, July 1870 - February 1871, 60 articles written by Engels for The Pall-Mall Gazette.

French Workers Party split

The split in the French Workers Party [Parti ouvrier] took place at the Congress at St. Etienne in September 25, 1882. The National Committee moved to exclude the Marxists from the Party as they could not "obey both the decisions of the Congress, and the will of a person who is himself located in London outside all Party control." The Marxist minority of the Congress, led by Guesde and Lafargue, retired from the Congress as a result of falsified votes the Possibilists used to gain the majority, and opened their own Congress in Rouen.

Regarding the Possibilists, Engels wrote to Bernstein on November 28, 1882: "These people are...anything but a workers' party. They are: however, in germ, what the people here [in London] are in full maturity: the tail of the bourgeois radical party.... They have no workers' programme at all. And in my opinion the workers' leaders who lend themselves to the production of a herd of working-class voting-cattle of this sort are guilty of direct treachery."