Hi

Higgins, Jim (1930–2002)

Born into a working-class family in Harrow, Jim Higgins joined the Young Communist League at 14 and left school at 16. Two years later he was apprenticed to the Post Office as a telecommunications engineer. After National Service in the early 1950s, he became active in both the Communist Party and the Post Office Engineering Union. He broke with the CP in 1956 following Khrushchev’s “secret speech” and the Soviet invasion of Hungary. Higgins read Trotsky voraciously, and joined a small group – Socialist Labour League – and then the Socialist Review Group which became the International Socialists.

By the 1960s he was a POEU branch secretary and was elected to the union’s national executive, but he gave up his union work to become IS’s full-time national secretary in the early 1970s. IS grew rapidly in the later 1960s and early 70s but in a burst of internal quarrels in the period 1973-76 he was forced out of the organisation and then built a new life as a journalist. He remained active as a writer and speaker at left wing meetings up until his death.

Hilbert, David (1862-1943)

German mathematician who reduced geometry to a series of axioms and contributed substantially to the establishment of Formalism in foundations of mathematics. His work in 1909 on integral equations led to 20th-century research in functional analysis; his Formalism, which treats mathematics as a series of symbols which can be rearranged according to various formal rules, sheds no light on the obvious relevance of mathematics to natural science, but led to the development of meta-mathematics, the systematic study of the comparative structures of mathematical theories, which was essential to subsequent elucidation of the problems of the foundations of mathematics by Gödel and others.

German mathematician who reduced geometry to a series of axioms and contributed substantially to the establishment of Formalism in foundations of mathematics. His work in 1909 on integral equations led to 20th-century research in functional analysis; his Formalism, which treats mathematics as a series of symbols which can be rearranged according to various formal rules, sheds no light on the obvious relevance of mathematics to natural science, but led to the development of meta-mathematics, the systematic study of the comparative structures of mathematical theories, which was essential to subsequent elucidation of the problems of the foundations of mathematics by Gödel and others.

Hilbert completed his PhD at the University of Königsberg in 1884, remaining there till 1895, after which he was appointed Professor of Mathematics at the University of Göttingen, where he remained for the rest of his life.

Hilbert introduced a highly original approach to the consideration of mathematical invariants which allowed the structure of mathematical theories to be themselves the subject of mathematical analysis in a way hither to unimagined. An invariant is that aspect of something which remains the same when a corresponding transformation is applied to something. The meaning of invariant is most easily understood in terms of geometrical transformations such as displacement (where shape and size are invariant) or dilation (where shape but not size are invariant). Hilbert proved that all invariants can be expressed in terms of a finite number. His new method allowed him to produce a set of axioms for Euclidean geometry which marked a turning point in the theory of axioms.

Much of Hilbert's fame rests on a list of 23 unsolved problems of mathematics he enunciated in Paris in 1900 in an address published as The Problems of Mathematics. Many of the problems have since been solved, and each solution has been an ‘event’.

Over the first two decades of the twentieth century, Hilbert struggled to construct an axiomatic foundation for mathematics for which he could prove that a finite number of steps of reasoning could not lead to a contradiction. However, Gödel’s 1931 theorem showed this to be unattainable: every consistent theory must contain propositions that are undecidable, he proved. Nevertheless, the development of logic after Hilbert was different, for he established the formalistic foundations of mathematics.

Hilbert's name is given to Infinite-Dimensional space, called Hilbert space, used as a conception for the mathematical anaysis of the kinetic gas theory and the theory of radiations.

Further Reading: Foundations of Mathematics, 1927. See also, Ernst Kolman and Sonya Yanovskaya's Hegel & Mathematics and Value & Quantity.

Hilferding, Rudolph (1877-1941)

A practicing physician, but had a long-time interest in structure and economics. Contributed to Die Neue Zeit and in 1904 wrote his classic Response to Böhm-Bawerk's in his criticism of Marxist economics, Karl Marx and the Close of His System.

Leader and teacher in the German Social Democratic Party prior to World War I and author of the book Finance Capital, an analysis of then-current capitalist development. He took a pacifist position during that war, which led him to the Independent Social Democrats (USPD), later to returning to the Social Democratic Party and become finance minister in the Stresemann cabinet in 1923 and the Mueller cabinet, 1928-30. He fled to France when the Nazis came to power, but the Petain regime turned him over to the Gestapo in 1940, and he died in a German prison. His major work was Finance Capital.

A practicing physician, but had a long-time interest in structure and economics. Contributed to Die Neue Zeit and in 1904 wrote his classic Response to Böhm-Bawerk's in his criticism of Marxist economics, Karl Marx and the Close of His System.

Leader and teacher in the German Social Democratic Party prior to World War I and author of the book Finance Capital, an analysis of then-current capitalist development. He took a pacifist position during that war, which led him to the Independent Social Democrats (USPD), later to returning to the Social Democratic Party and become finance minister in the Stresemann cabinet in 1923 and the Mueller cabinet, 1928-30. He fled to France when the Nazis came to power, but the Petain regime turned him over to the Gestapo in 1940, and he died in a German prison. His major work was Finance Capital.

See Rudolf Hilferding Archive.

Hill, Christopher (1912-2003)

Marxist historian whose radical interpretation of the 17th century changed the way we think about the English revolution .

Marxist historian whose radical interpretation of the 17th century changed the way we think about the English revolution .

Christopher Hill was the commanding interpreter of 17th-century England, and of much else besides. As a public figure, he achieved his greatest fame as master of Balliol College, Oxford, a post he held from 1965 until 1978. Yet it was as the defining Marxist historian of the century of revolution, the title of one of the most widely studied of his many books, that he became known to generations of students around the world. For all these, too, he will always be the master.

It would be a pardonable exaggeration to say that Hill created the way in which the people of late 20th-century Britain – and the left in particular – looked at the history of 17th-century England. As he never tired of pointing out, some of the themes he illuminated so richly had already been explored by left-wing scholars in the 1930s. But from 1940, when he published his tercentenary essay, The English Revolution 1640, his own voluminously expanding and unfailingly literate work became the starting point of most subsequent interpretation, even for those who rejected his method and conclusions.

No historian of recent times was so synonymous with his period of study; he is the reason why most of us know anything about the 17th century at all. He was, EP Thompson once said, the dean and paragon of English historians.

Hill was born in York, where his father was a solicitor. His parents were Methodists, a fact to which he attributed his lifelong political and intellectual apostasy. Though his life was to be the embodiment of a secularised form of dissent, his high moral seriousness and egalitarianism surely had roots in this radical Protestant background.

At St Peter's school in York, his academic prowess was immediately evident. It is said that, when Hill was 16, the two Balliol dons – Vivien Galbraith and Kenneth Bell – who marked his entrance papers agreed to award him 100%, before travelling to York to capture him for the college and prevent him going any further with a Cambridge application. Galbraith, in particular, was to remain an immense influence.

Hill's association with Balliol was to continue, with only brief interruptions, from his arrival as an undergraduate in 1931 until his retirement as master 47 years later. Academic honours regularly fell his way, starting with the prestigious Lothian prize in 1932, and continuing with a first-class degree in 1934 and an All Souls fellowship that winter. But he was a successful rugby player too, the scorer of a famous cup-winning try for Balliol. Even more lastingly, he had become a Marxist.

Exactly when and why this happened is uncertain, since Hill was always notoriously inscrutable about discussing his personal life. He once claimed it came about through trying to make sense of the 17th-century metaphysical poets, but although he read Marx as an undergraduate, the moment of his conversion to communism is elusive.

His contemporary, RW Southern, once teasingly remembered “a time when Christopher was not in the least bit leftish", but Hill was an undergraduate during the period of the great depression, the hunger marches, the New Deal, Hitler's rise (he visited the Weimar Republic before going up to Oxford), and the first (favourable) impact of Stalin in the west. He was a regular attender at GDH Cole's Thursday Lunch Club, where, as he once put it, “I was forced to ask questions about my own society which had previously not occurred to me.”

Certainly by the time he graduated, Hill had joined the Communist party. In 1935, he spent a year in the Soviet Union, during which he was very ill, but also formed a lasting affection for Russian life – and a somewhat less lasting one for Soviet politics.

After Moscow, he had two years as an assistant lecturer at University College, Cardiff, before returning to Balliol as a fellow and tutor in modern history. In 1940, he was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry, before becoming a major in the intelligence corps and being seconded to the Foreign Office from 1943 until the end of the war. This was, to put it mildly, an intriguing period, about which he rarely let fall much detail.

By this time, he had begun to publish, at first pseudonymously, articles and reviews which, among other things, did much to draw attention to the burgeoning Soviet school of English 17th-century studies. Then, in 1940, arising out of intensive debate among a group of Marxist historians, who included Leslie Morton, Robin Page Arnot and – particularly influential on Hill – Dona Torr, came the decisive The English Revolution 1640.

The essay was originally published as one of a collection of three reflections (the others were by Margaret James and Edgell Rickword). Hill's contribution, which was subsequently published alone, was a no-holds-barred assertion of the revolutionary nature of England between 1640 and 1660, and an assault on the traditional presentation of these years as an aberration in the stately continuity of English history.

“I wrote as a very angry young man, believing he was going to be killed in a world war,” Hill later told an interviewer. The book, he said, “was written very fast and in a good deal of anger, [and] was intended to be my last will and testament.” It has rarely, if ever, been out of print since.

The discussions surrounding Hill's essay also produced, in 1946, the Communist Party Historians Group, an association he regarded as “the greatest single influence” on his subsequent work. This formidable academy, which included Edmund Dell, Maurice Dobb, Rodney Hilton, Eric Hobsbawm, James Jeffreys, Victor Kiernan, George Rudé, Raphael Samuel, John Saville and Dorothy Thompson, has a good claim to have redefined the study of history in Britain, especially after the launch, in 1952, of the journal Past And Present, of which Hill rapidly became the moving spirit and, later, the doyen. It also generated the path-breaking collection of documents, The Good Old Cause, that he edited with Dell in 1949.

The active, 20-year involvement with communism, which also led to his short biography, Lenin And The Russian Revolution (1947), came to a crisis after the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956. Along with many in the CP, Hill had become disenchanted with the party's lack of democracy and its reluctance to criticise the Soviet Union. Both issues came to a head in the late weeks of 1956, though his own break did not come until the following year. He was appointed to a CP review of inner-party democracy, but the rejection of the critical minority report, written by Hill (with Peter Cadogan and Malcolm MacEwen), precipitated his final departure.

These were watershed years in Hill's personal life too. A wartime marriage to Inez Waugh, the former wife of a colleague, produced a home life which combined the high seriousness of Balliol Marxism with an extravagant bohemianism. It also produced their daughter Fanny Hill, later a dashing figure on the Oxford scene, who drowned off the Spanish coast in her 40s. The marriage collapsed early and, in 1956, he married again, this time to Bridget Sutton, then a history tutor with the Workers' Educational Association in Staffordshire. Turbulence was replaced by the single greatest happiness of Hill's life. With Bridget, he had a son and two daughters, one of whom died in a car accident.

After 1957, Hill's career ascended to new heights as he began the remarkable output of books on which his reputation will rest, and which continued undiminished until he was well into his 80s. Hill always argued that the connection between leaving the CP and his wider fame was post-hoc rather than propter-hoc, and it is certainly true that 1956-57 caused no revolution (let alone a counter-revolution) in his analysis of the English revolution. On the other hand, the Bridget effect can hardly be underestimated.

If the steady flow of books which began with Economic Problems Of The Church (1955) can, to some extent, be seen as a succession of more scholarly explorations of the themes sketched out in the early didactic essays, they also reflect the extraordinary sweep of Hill's interests and mind. Central to the whole project was a patient fascination with religion, represented, in particular, in his attempt to understand the revolutionary power of puritanism.

But Hill's explorations were in no way bound by traditional or preconceived theories. The single, most striking and controversial aspect of his method was the way in which he subtly identified intellectual connections, currents and continuities between the most unlikely pieces of evidence – from scraps of court records to Paradise Lost and Pilgrim's Progress. His use of literary sources was one of his most fascinating characteristics.

Many of the tasks he set himself were laid out in his next book, Puritanism And Revolution (1958). They were further explored in Society And Puritanism In Pre-Revolutionary England (1964) and the remarkable Intellectual Origins Of The English Revolution (1965, and extensively revised 31 years later), this last based on his 1962 Ford lectures. Alongside came more popular works of exegesis – a Historical Association pamphlet on Cromwell (1958), the bestselling (but not adulatory) biography God's Englishman (1970), the textbook The Century Of Revolution (1961) and the hugely successful Penguin economic history, Reformation To Industrial Revolution (1967).

Those who heard Hill deliver the lectures on which it is based – lectures delivered in a nervous, slightly stuttering voice – will always reserve a special place for his 1972 study of radical and millenarian ideas, The World Turned Upside Down. Not only was this one of the very few history books to be turned into a play (at the National theatre), it was also a work made more exciting by the time in which it was written, an era of counter-cultural energy which Hill observed (and quietly celebrated) from the Balliol master's lodgings.

This was a period of immense academic daring (and, thought some, of over-reaching) as Hill scythed through received tradition in his study of AntiChrist In 17th-century England (1971) and his controversial study of Milton And The English Revolution (1977), which, like many of his later works, was written at the plain but lovely house in Périgord which Bridget badgered him into buying in 1969.

Meanwhile, in 1965, Hill had defeated Ronald Bell in the election for master of Balliol, a success which caused raised eyebrows (it was only 10 years or so since academics with Hill's politics had been, to all intents and purposes, blacklisted from many posts) and much press attention. His tenure was deft and collegiate, and he tried to maintain his teaching and research amid the administrative and ceremonial duties. He never seriously hid his enthusiasm for the two main innovations of his mastership – the opening of male-only Balliol to women, and the representation of students on the college governing body. “Common sense varies among the young,” he admitted, “as among the old.”

Retirement found his productivity undiminished. He moved to Sibford Ferris, on the Cotswold hills, and, for two years, worked as a visiting professor at the Open University, an entirely characteristic effort to bring his learning to a wider audience. Then he settled down to further books: Some Intellectual Consequences Of The English Revolution (1980); The World Of The Muggletonians (1983); and The Experience Of Defeat (1984), an account of the Restoration made poignant by the reverses 20th-century leftwing politics were suffering at the time.

A marvellously vivid study of Bunyan followed in 1988, before The English Bible In 17th-century England (1993) and Liberty Against The Law (1996). Three volumes of essays were published in the 1980s – throughout his life, Hill wrote some of his most challenging and original work in articles and reviews.

Hill was honoured by an OUP festschrift, Puritans And Revolutionaries, when he retired from Balliol in 1978, and Verso published a series of tributes and criticisms, Reviving The English Revolution, 10 years later. Yet, for the last 20 years of his life, he became once again a more controversial figure.

His methodology was famously assaulted by JH Hexter in a Times Literary Supplement review in 1975, and his assessment of Milton was powerfully denounced by Blair Worden. A reaction against his big reading of 17th-century history took root in the work of Conrad Russell, John Morrill and others. Yet Morrill's tribute in 1989 – “If we can be sure that the 17th century changed England and Englishmen more than any other century bar the present one, we owe that recognition to him more than to any other scholar” – shows how, even in relative eclipse, Hill remained the central point of reference in 17th-century studies.

People always felt there was something enigmatic about Hill. Whether as a friend walking through Oxfordshire or the Dordogne, as a tutor hunched in his armchair discussing an essay – and still more on formal occasions – he kept his cards close to his chest, forcing you to do the talking, making you listen to what you were saying in the way that he was listening too. But then he would make a joke, often just a pointed ironic observation, that made you love him. As someone once said, although he affected to be severe, he could not help being benign.

But tough too. Always. Hill once gave a radio talk marking the centenary of the publication of Das Kapital. He ended it by telling how, in old age, Marx had bumped into a fellow revolutionary from the 1848 barricades, now prosperous and complacent. The acquaintance reflected that, as one got older, one became less radical and less political. “Do you?” Marx replied. “Do you? Well, I do not!” And nor, he clearly intended us to understand, did Christopher Hill.

From The Guardian (UK), February 26, 2003.

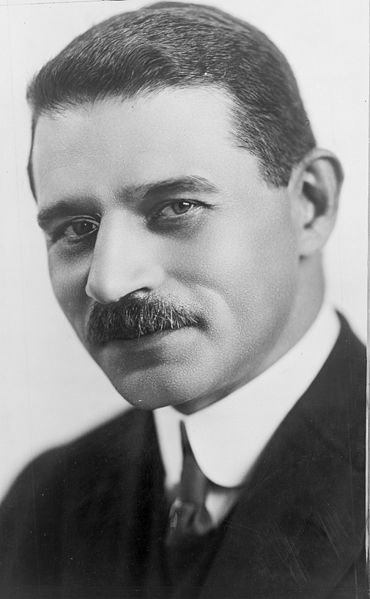

Hillquit, Morris (1869-1933)

Morris Hillquit was a founder and leader of the Socialist Party of America, as well as a prominent labor lawyer in New York City’s Lower East Side during the early 20th century.

Morris Hillquit was a founder and leader of the Socialist Party of America, as well as a prominent labor lawyer in New York City’s Lower East Side during the early 20th century.

The future Morris Hillquit was born Moishe Hillkowitz in Riga, Latvia, on August 1, 1869, the second son of German-speaking Jewish factory owners.[1] From the time he was 13, young Moishe attended a non-Jewish secular school, the Russian language Alexander gymnasium.[2] At the age of 15, in 1884, Moishe’s father, Benjamin Hillkowitz, lost his factory in Riga and decided to leave for America to improve the family’s financial situation.[3] In 1886, Benjamin sent for the rest of the family and they emigrated to the United States, settling in New York City.[4] The family remained poor in the new world, living in a tenement in a predominately Jewish area of the lower East Side.[5] In this period Moishe worked various short-term jobs in the New York city textile industry and as a picture frame maker in a factory.[6]

Hillquit’s biographer Norma Fain Pratt remarks that Moishe was quickly drawn to the socialist movement in America:

Almost as soon as he settled in New York, Hillquit was drawn into East Side Jewish radical circles. He was then a small (5’4”), slightly built, frail adolescent with dark hair, dark oval-shaped eyes, and a gentle charming manner. He was immediately attracted to other young Jewish immigrants, mostly former students, now shop workers, who considered themselves intellectuals – a new radical intelligentsia.... For the most part their radicalism was rooted in their experiences in the European socialist and anarchist movements. But emigration and economic hardships in the United States also contributed to their further radicalization. As foreigners in America they were situated far enough outside the society to observe its failings. As frustrated but literate people, they were ambitious enough to participate in it. These young intellectuals were interested in finding alternatives to their present circumstances; their solution was to transform them.[7]

On his 18th birthday in August 1887, the future Hillquit joined the Socialist Labor Party of America, brought into the ranks by a fellow garment worker and Russian language socialist newspaper editor, Louis Miller. Moishe became a member of Section New York’s Branch 17, a Russian-speaking unit established by Jewish emigrés from tsarist Russia not long before his joining.[8]

Within a year or so of joining the SLP, biographer Pratt notes, Moishe Hillkowitz became one of the party’s leading crusaders against anarchism, publishing a lengthy article “Sotzializm un anarchizm” in the Arbeter zeitung [Workers’ News], a Yiddish newspaper that he helped to establish. Hillkowitz contrasted the individualism of anarchism with the communalism of socialism in this piece.[9] During this time the 19 year old HIllkowitz worked as the business manager of the Arbeter zeitung, a paper which was jointly founded with Abraham Cahan, Louis Miller, and Morris Winchevsky in an effort to speak to the city’s Yiddish-speaking immigrant working class about socialism in their own idiom.[10] Hillkowitz, ironically, was not fluent in Yiddish, having been raised with the German and Russian languages.[11]

He helped to found the United Hebrew Trades, a garment workers’ union formed in 1888, while writing for the Arbeiter Zeitung, a Yiddish-language newspaper. He later graduated from New York University Law School in 1893.

Hillquit led the departure of a dissident faction from Daniel De Leon’s Socialist Labor Party in 1899, a group which united with the Chicago-based Social Democratic Party of Victor Berger and Eugene V. Debs in 1901 to form the Socialist Party of America (SPA). He remained a foremost political leader of that organization for the rest of his life, said to have espoused “the most popular brand of evolutionary Socialism within the Socialist Party."[12]

In 1904, Hillquit attended the International Socialist Conference at Amsterdam and was involved in moving the proposed Anti-Immigration Resolution, which opposed any legislation which forbade or hindered the immigration of foreign working men, some of which were forced by misery to migrate. However, following “further consideration of the fact that workingmen of backward races (Chinese, Negroes, etc.) are often imported by capitalists to keep down the native workingmen by means of cheap labour, which constitutes a willing object of exploitation, lives in an ill-concealed state of slavery” as something which should be combatted by Social Democracy “with all its energy.”

Hillquit ran for US Congress in the New York 9th Congressional District in 1908, winning 21.23% of the vote in a losing effort against a Democratic incumbent.[13] After this campaign, Hillquit turned his attention to inner-party affairs. This brought him into conflict with the SPA’s syndicalist Left Wing. His biographer notes at least four serious points of departure between Hillquit and the Industrial Workers of the World wing of the party: (1) a disbelief in the stability and efficacy of industrial unions; (2) A distaste for the strike-oriented tactics of the IWW as opposed to collective bargaining; (3) A belief in the separation of functions between the political and labor wings of the workers’ movement, as opposed to the IWW’s desire to make industrial organization primary; and (4) The radical tone of IWW propaganda, which Hillquit believed served to alienate much of society from the socialist movement and marginalize the left.[14] His biographer declares that

“His leadership fanned the fires of Party disagreement and although [Hillquit] was not alone in causing the break in 1913 with an important segment of its left wing, he certainly made a major contribution towards this unfortunate rupture."[15]

In 1911, IWW leader William “Big Bill” Haywood was elected to the National Executive Committee of the Socialist Party, on which Hillquit also served. The syndicalist and the electoral socialist squared off in a lively public debate in New York City’s Cooper Union on Jan. 11, 1912. Haywood declared that Hillquit and the socialists ought to try “a little sabotage in the right place at the proper time” and attacked Hillquit for having abandoned the class struggle by helping the New York garment workers negotiate an industrial agreement with their employers. Hillquit replied that he had no new message rather than to reiterate a belief in a two-sided workers movement, with separate and equal political and trade union arms. “A mere change of structural forms would not revolutionize the American labor movement as claimed by our extreme industrialists,” he declared.[16]

Hillquit’s battle against the syndicalist left of the party continued at the 1912 National Convention, held in May in Indianapolis. Hillquit’s biographer notes that

“As chairman of the Committee on Constitution he more than likely authored the amendment to the Party’s Article II, Section 6, which provided for the expulsion from the Party of ‘any member of the party who opposes political action or advocates crime, sabotage, or other methods of violence as a weapon of the working class to aid in its emancipation....’” He voiced his justification for this anti-sabotage amendment by reassuring the convention that ‘if there is one thing in this country that can now check or disrupt the Socialist movement, it is not the capitalist class; it is not the Catholic Church; it is our own injudicious friends from within.’"[17]

The issue of “syndicalism vs. socialism” was bitterly fought over the next two years, consumated by “Big Bill” Haywood’s recall from the SP’s NEC and the departure of a broad section of the left wing from the organization. The radical wing never forgave Hillquit for his anti-IWW orientation of these years and made him a major whipping boy in the big split that was to come.

As a staunch internationalist and antimilitarist, Hillquit represented the ideological center of the Socialist Party during the years of World War I, which controlled the organization in coalition with the more pragmatist right wing exemplified by such locally-oriented leaders, politicians, and journalists as Victor Berger, Daniel Hoan, John Spargo, and Charles Edward Russell. He was elected to the SP’s governing National Executive Committee on multiple occasions and was a frequent speaker at national conventions of the party. Due to his foreign birth, however, Hillquit was not constitutionally eligible to serve as President or Vice President of the United States and was thus never a candidate of the party for national office.

Hillquit was a principal co-author of the resolution against the United States’ entry into World War One which was passed overwhelmingly both by an emergency Socialist Party convention held just after the April 6th, 1917, U.S. declaration of war and by a subsequent membership referendum.[18] Despite official repression, popular patriotic pressure and vigilante action against the SP of A’s organization, members and press, Hillquit never wavered on the issue of intervention, staunchly backing Debs, Berger, Kate Richards O’Hare and other socialists charged under the Espionage Act for opposing the war effort.

On January 26, 1916, Hillquit was part of a three person delegation to President Wilson to advocate part of the Socialist Party’s peace program, which proposed that “the President of the United States convoke a congress of neutral nations, which shall offer mediation to the belligerents and remain in permanent session until the termination of the war.” A resolution to this effect had been offered in the House of Representatives by the SP’s lone Congressman, Meyer London of New York, and Wilson received Hillquit, London, and socialist trade unionist James H. Maurer at the White House, along with various other delegations. Hillquit later recalled that Wilson was at first “inclined to give us a short and perfunctory hearing” but as the Socialists made their case to him, the session “developed inot a serious and confidential conversation.” Wilson told the group that he had already considered a similar plan but chose not to put it into effect because he was not sure of its reception by other neutral nations. “The fact is,” Wilson claimed, “that the United States is the only important country that may be said to be neutral and disinterested. Practically all other neutral countries are in one way or another tied up with some belligerent power and dependent on it."[19]

Beginning in June 1917, Hillquit served as chief defense lawyer in a series of high profile cases on behalf of various socialist magazines and newspapers. The Wilson administration, headed in the matter by Postmaster General Albert Burleson, began to systematically ban specific issues or entire publications from the mail, or to force publications into financial peril by denying them access to low cost periodical rates. Hillquit argued cases on behalf of a number of important radical publications, including Max Eastman’s radical artistic and literary magazine, The Masses; the two socialist dailies – the New York Call and the Milwaukee Leader; the SP’s official weekly, The American Socialist; the popular monthly Pearson’s Magazine; and the Yiddish language Jewish Daily Forward. In each of these cases, Hillquit argued that the socialist press was truly “American” and that a socialist definition of “patriotism” included the freedoms of press and speech and the right to criticize in a democratic society.[20] Hillquit was unsuccessful in winning access to the mails for the papers he represented, but he did manage to keep the proprietors of The Masses out of prison.

In the summer of 1917, with nationalism and pro-war sentiment sweeping the nation, Hillquit ran for Mayor of New York City. Hillquit’s campaign was based on an anti-war platform and commitment to economical public services and drew the diverse support both of committed socialists, pacifists and other anti-war activists, and pro-war liberals endorsing his campaign as a protest against the government’s “sedition” policy, which effectively served to curb freedoms of speech and press.[21] Hillquit seems to have been largely immune from attack by the Socialist Party’s left wing or other radicals during this high-profile campaign,[22] which ended with Hillquit collecting an impressive 22% of the citywide vote. This campaign, combined with the ongoing electoral success of Congressman Meyer London (elected as a Socialist in 1915, 1915, and 1921) marked the high point for Socialist Party politics in New York City.

As a member of the SP’s National Executive Committee Hillquit worked closely with National Secretary Adolph Germer and James Oneal to defend the party from what in modern parlance might be described as an “unfriendly takeover” by its revolutionary socialist left wing. However, due to ill health Hillquit did not participate in the pivotal 1919 Emergency National Convention at Chicago which formalized the split of the left wing from the Socialist Party to form the Communist Labor Party and the Communist Party of America. Instead, Hillquit was ensconced in a sanitorium in upstate New York, recovering from another bout of tuberculosis, and was informed about the events of the convention after the fact.

In 1920 Hillquit served as the lead attorney in the unsuccessful defense of the five democratically-elected Socialist assemblymen expelled from the New York State Assembly. Hillquit’s efforts to see Assemblymen Orr, Claessens, Waldman, DeWitt, and Solomon restored to office was ultimately unsuccessful.

From 1922 through the election of 1924, Hillquit was a leading advocate of Socialist Party participation in the Conference for Progressive Political Action (CPPA).

In 1932, shortly before his death from tuberculosis, Hillquit received over one-eighth of the vote in his second campaign for Mayor. This proved to be Hillquit’s final electoral run; during his life, he had been twice a candidate for Mayor of New York and on five times a nominee for Congress.

One of the buildings of the East River Housing Corporation, a housing cooperative started by the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union in Cooperative Village on the Lower East Side, was named in Hillquit’s honor.

Hillquit’s papers are housed at the State Historical Society of Wisconsin at Madison and are available on microfilm.

Hillquit was first and foremost an orator, delivering a torrent of public talks on socialist themes to various audiences throughout his life. In his memoirs, Hillquit conservatively estimates the total number of such speeches to have been “at least 2,000.” He often appeared in public debates taking up the socialist banner. He wrote frequently for popular magazines and the party press but fairly infrequently for publication in leaflet or pamphlet form. Despite the fact that Hillquit was not a prolific pamphleteer, he did author of a number of substantial books, including a serious academic history of socialism, History of Socialism in the United States (1903, revised 1910 – translated into both Russian and German); works of popularization, such as Socialism in Theory and Practice (1909) and Socialism Summed Up (1912); a short theoretical piece, From Marx to Lenin (1921); as well as a posthumously published memoir, Loose Leaves from a Busy Life (1934).

Books

Hillquit, Morris:

- From Marx to Lenin. New York: Hanford Press, 1921.

- History of Socialism in the United States. (1903) New York: Funk & Wagnalls, Revised and Expanded (5th) edition, 1910 (reprinted in 1971 by Dover Publications, New York, ISBN 0-486-22767-7).

- Loose Leaves from a Busy Life. New York: Macmillan, 1934.

- Socialism in Theory and Practice. New York: Macmillan, 1909.

- Socialism on Trial. New York: B.W. Huebsch, 1920.

- Socialism: Promise or Menace? New York: Macmillan, 1914. – written debate with Father John A. Ryan, a leading Catholic social justice theorist.

- Socialism Summed Up. New York: H.K. Fly, 1912.

Others:

- Epstein, Melech, Profiles of Eleven: Profiles of Eleven Men Who Guided the Destiny of an Immigrant Society and Stimulated Social Consciousness Among the American People. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1965.

- Esposito, Anthony V., The Ideology of the Socialist Party of America, 1901-1917. New York: Garland Publishing, 1997.

- Hyfler, Robert, Prophets of the Left: American Socialist Thought in the Twentieth Century. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1984.

- Howe, Irving, World of Our Fathers. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976 (ISBN 0-15-146353-0).

- Kipnis, Ira, The American Socialist Movement, 1897-1912. New York: Columbia University Press, 1952

- Pratt, Norma Fain, Morris Hillquit: A Political History of an American Jewish Socialist. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1979 (ISBN 0-313-20526-4).

- Quint, Howard, The Forging of American Socialism: Origins of the Modern Movement. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1953; 2nd edition (with minor revisions) Indianapolis, Indiana: Bobbs-Merrill, 1964

- Salvatore, Nick, Eugene V. Debs: Citizen and Socialist, Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1982 (ISBN 0-313-20526-4).

- Shannon, David A. The Socialist Party of America: A History. New York: Macmillan, 1950 (reprinted in paperback by Quadrangle Books, Chicago, 1967).

- Weinstein, James, The Decline of Socialism in America, 1912-1925 New York: Monthly Review Press, 1967 (first paperback edition, New York: Vintage Books, 1969)

Periodicals

- American Socialist/Eye Opener (Chicago) (1914-1919)

- New Leader (New York) (1924-1934)

- New York Worker/New York Call (1907-1923)

- Socialist World (Chicago) (1919-1925)

Footnotes

1. Norma Fain Pratt, Morris Hillquit: A Political History of an American Jewish Socialist. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1979; page 3. ISBN 0-313-20526-4.

Pratt, Morris Hillquit, p. 4.

2. Pratt, Morris Hillquit, p. 5.

3. Pratt, Morris Hillquit, p. 5.

4. Pratt, Morris Hillquit, p. 6.

5. Pratt, Morris Hillquit, p. 6.

6. Pratt, Morris Hillquit, pp. 6-7.

7. Pratt, Morris Hillquit, pp. 8-9.

8. Hillkowitz, “Sotzializm un anarchizm,” Arbeter zeitung, April 8, 1890. Cited in Pratt, Morris Hillquit, p. 11.

9. Pratt, Morris Hillquit, pp. 14-15.

10. Pratt, Morris Hillquit, p. 16.

11. Robert Hyfler, Prophets of the Left: American Socialist Thought in the Twentieth Century. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1984; p. 39.

12. Pratt, Morris Hillquit, p. 96.

13. Pratt, Morris Hillquit, pp. 99-100.

14. Pratt, Morris Hillquit, p. 99.

15. Hillquit, “What shall the Attitude of the SP Be Toward the Economic Organization of the Workers?” (Haywood Debate) in Hillquit Papers; quoted in Pratt, Morris Hillquit, p. 106.

16. Pratt, Morris Hillquit, p. 108.

17. War proclamation and program adopted at the National Convention of the Socialist Party of the United States, St. Louis, Mo., April 1917 accessed June 18, 2008. Available in print as “St. Louis Manifesto of the Socialist Party 1917” in Socialism in America from the Shakers to the Third International: a documentary history, edited by Albert Fried, New York: Doubleday Anchor edition, 1970; page 521. See also chapters IV and V of David Shannon’s Socialist Party of America, especially pages 93-98.

18. Morris Hillquit, Loose Leaves from a Busy Life, New York: Macmillan, 1934; pg. 161.

19. Pratt, Morris Hillquit, p. 139.

20. Pratt, Morris Hillquit, p. 129.

21. Pratt, Morris Hillquit, p. 129.

22. Hillquit, Loose Leaves from a Busy Life, p. 80.

Hindenburg, Paul von Beneekendorif und von (1847-1934)

Prussian militarist. Fought in war against France 1870-71. General in 1903. Retired 1911. Recalled at beginning of War. Victor at Tannenburg 1914 and the Masurian Lakes 1915 against Russia. Later Field Marshal. Succeeded Ebert as President 1925 Co-existed with Hitler from 1932 till his death.

Hirsch, Carl (1841-1900)

German Social-Democrat, journalist, former Lassallean. In 1868 he edited the Demokratisches Wochenblatt [Democratic Weekly] with Wilhelm Liebknecht; in 1870 he was editor of the Social-Democratic Bauern and Bürgerfreund [The Peasants' and Citizens' Friend]. During Liebknecht's imprisonment in the winter of 1870-71 Hirsch replaced him as editor of the Volksstaat. In 1874 he settled in Paris where he took part in the workers' movement. After his expulsion from Paris he went to Belgium where he published a weekly called the Laterne (1878-79) in which he sharply criticised the opportunist attitude of a section of the German Social-Democratic leaders. In the 'eighties he lived in Paris.

Hirsch, Werner (1899–1937?)

Son of Jewish banker. In USPD in 1917, then in Spartacus League, where he supported Jogiches. Arrested at beginning of 1918, freed and conscripted into navy. Took part in Kiel mutinies, helped organise People’s Naval Division. Delegate to KPD(S) Foundation Congress. Distanced himself from Party after Levi was expelled, became press correspondent in Vienna. Returned to KPD (Kommunistischen Partei Deutschlands/German Communist Party) in Germany in 1924, as journalist in 1926. Chief Editor of Die Rote Fahne in 1930, secretary to Thaelmann in 1932. Arrested in 1933, freed in 1934, wrote a pamphlet on Nazi camps. Went to USSR in 1937, arrested as ‘spy’ and shot.

Hitler, Adolph (1889-1945)

German fascist dictator. Leader of the Nazi Party. German Chancellor in 1933 and Führer of the Third Reich after 1934.

See Marxists on Fascism Archive.