History of Algerian Independence

French Colonization: For over 300 years Algeria was an autonomous province of the Ottoman Empire – after the empire helped overthrow Spanish captivity of Algeria in 1518. The autonomous Algeria was very powerful, with a fleet that ruled all the Mediterranean while European nations payed taxes to cross it – those who refused to recognize Algeria’s claim to the sea would have their ships captured and ransomed off. As capitalism advanced throughout Europe, international trade began to slowly develop in earnest, and property claims over water was a fundamental enemy. In 1815, the United States sent a fleet across the Atlantic to battle Algeria, with mixed results. The following year the English and Dutch sent a second, combined fleet to crush Algerian might – but were unable to beat algerian tactical supremacy. In 1830, the French invaded and successfully suppressed Algeria, capturing the capital port city of Algeirs and by 1834, Algeria was annexed as a colony of France.

Under french domination, Algerians could not hold public meetings nor even leave their homes without permission. French state racism kept Algerians at the bottom of society, working as servants, unskilled labourers and peasants, while only French citizens or other whites were allowed skilled jobs and positions in the social institutions (from the police to the government).

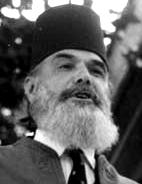

After the Russian Revolution, the Algerian Communist Ahmed Messali Hadj began underground struggles to build a revolutionary movement to overthrow French Colonialism. By the second world war, Ferhat Abbas, once a well-known Algerian social-democratic reformist, became a Communist and joined with Hadj to build a militant workers party – Friends of the Manifesto and Liberty.

See Messali Hadj Archive.

See Nothing is Lost, from Alger Républicain, June 1945

and Common Declaration of the Socialist and Communist Parties of Algiers, 1945

Ouradour-sur-Glane in Algeria, Ohé Partisans! No. 4 August 1945

In 1947, fearful of the growing nationalistic uprisings in the wake of the second world war, the French government established a parliamentary assembly in Algeria, made up of half European and Algerian delegates, with the purpose of upholding French colonial rule. It did not last.

In March of 1954, Ahmed Ben Bella, an ex-sergeant in the French army who was deported to Egypt for his leftist political beliefs, joined eight other Algerian exiles to form what would become the National Liberation Front (FLN). On November 1, 1954, just a few months after it’s creation, the FLN heroically began coordinated attacks on government buildings, military and police posts, and communications installations.

See Proclamation. To the Algerian people November 1, 1954

and The Saboteurs of our Struggle 1955

The FLN was waging a guerrilla war, much like their ancestor and hero, Abd al-Qadir, who led a guerilla struggle for 13 years at the outset of French rule in 1834. By 1957, the guerrilla’s made such progress that the French desperately called in 400,000 soldiers to bolster their occupation of the rising nation. Atrocities were committed on both sides: the genocidal French slaughtered entire villages of Algerians, while certain groups within the FLN used terrorism against the white civilian population.

See the Editorial in the first issue of “El Moudjahid”, published by the FLN in 1956,

Why the Communist Voted in Favor of the Government, Jacques Duclos, March 1956

Ali-la-Pointe, hero of the battle of Algiers

and Letter to the Europeans of Algeria, Algerian Communist Party, October 1957.

The French erected electrified fences along the Tunisian and Moroccan borders to restrict the free movement of the FLN; while they began rounding up all Algerians in concentration camps. Outraged by the lack of even more thorough repression in May, 1958, French settlers overthrew their own government, and installed General Charles de Gaulle as the ruler of Algerian France.

Not all French people turned their backs on the Algerians however. There were “pied-noir” (European Algerians) who supported the liberation war, and one of these was Fernand Iveton.

In less than a year however, de Gaulle openly announced his association with the French government, and explained that the only way out was a tactical retreat – giving in to demands for free elections. French settlers unsuccessfully tried again to overthrow General de Gaulle, including terrorist attacks in Paris, while their genocidal war against the FLN and Algerians continued.

- Open Letter from Henri Maillot, 4 April 1956

- Appeal of the FLN to Our Israelite Compatriots, 1 October 1956

- Save Djamila Bouhired, April 1958

- Minutes of a Meeting between the FLN and the PCF, 30 May 1958

- “Manifesto of the 121,” published by French independent Leftists, Aug 1960

- The 121, La Vérité des Travailleurs, #111, December 1960

- Ben Bella’s response

- Letter of the FLN to the Harkis, 14 July 1960.

- Declaration of the Michel Pablo and Sal Santen Support Committee, November 1960.

- A First-Hand Account of Torture, by Omar Hamadi, 5 December 1960

- Principles and Refusing Army Service, La Vérité des Travailleurs, November 1960

- The Algerian Revolution is Six Years Old, La Vérité des Travailleurs, November 1960

- Letter of the French Federation of the FLN, 10 October 1961

- The Massacre of 17 October 1961

- Appeal to the French, 22 October 1961

- To the Israelites of Algeria, FLN-ALN General Staff 1962

- The Crémieux Decree declaring the Jews native to Algeria to be French citizens, 1870

See Algeria and the defeat of French Humanism,

The Arab Revolution, Michael Pablo November 1958, Preface, June 1959, and

Alain Krivine on Algeria, 1956-62.

My Discovery of Algeria, by Henri Alleg

In March of 1962, a cease-fire was established: by July a nation-wide referendum was held with the Algerian people voting overwhelmingly for independence, with presidential elections scheduled for September.

Independence: (1962 - 1991) The eight year war of independence extracted a heavy, one-sided toll. One hundred thousand French settlers and soldiers had died, while over one million Algerian civilians and guerrillas were executed and killed.

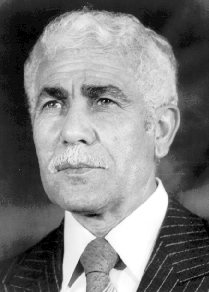

Ahmed Ben Bella, with the support of Colonel Houari Boumedienne, the National Liberation Army chief of staff, was elected the first president of Algeria in 1962. Algeria was declared an Arab-Islamic socialist state with a single party political system: the FLN. Economic centralized planning began, private industry was nationalized and land reform began. The liberation of women from their former constraints began in earnest, while Islam and Arabic were recognized as the "essential spiritual force" of the revolution (only Muslims were allowed to serve as president of the Republic), while freedom of religion was allowed to all. A tremendous amount of power was vested in the single person of the president however, and grass roots democratic organisations essentially did not exist. A constitution was passed by popular referendum in 1963 to this effect.

>> 1963: Constitution of Algeria

In 1965, Defence Minister Houari Boumedienne broke the electoral process and staged a bloodless coup which imprisoned Ben Bella, and installed himself in power until 1978. He formed a 26-member Council of the Revolution – staffed by officials of the military – a council that became the country’s highest government body. Boumedienne began to develop the country’s oil resources and industry, while he held onto some tenants of social development, and thus mass education and literacy became a primary focus while agricultural land reform continued.

In 1978, Colonel Chadli Benjedid became the second elected president of Algeria, and began to relax the government’s authoritarian practices, pardoning for example Ahmed Ben Bella in 1980, though he continued to follow Boumedienne’s practice of putting the military into the political arena. Benjedid was re-elected to the presidency in 1984, this time because he ran unopposed. Soon however, world oil prices fell and the economy began to weaken – causing widespread rioting in 1985, when some began calling for an Islamic government. Benjedid responded by initiating a programme of reforms, including removing some of the military dominance in government, and introduced small-scale privatization and decentralization. Regardless, in October 1988, Algeria exploded into riots again.

The government responded by creating a new constitution in February 1989, reducing the role of the FLN, allowing political opposition, restricting the role of the army to defence matters, and giving public sector employees the right to strike. As a result of these allowances, the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS), who had initially been united with the socialist FLN under Ahmed Ben Bella (who was himself a Muslim), won an overwhelming victory over the FLN in municipal and provincial elections in 1990, and in the December 1991 general elections, the FIS swept the FLN in the first round of elections.

Civil War: (1991 - present) The military then brutally crushed Algeria’s re-emerginig democracy – forcing the FLN’s Benjedid to resign immediately, and thereafter calling a complete halt to the electoral process and suspending the parliament. A High Committee was established with Mohammed Boudiaff appointed as president. Both the FLN and FIS strongly suspected Western assistance to the military in order to smash the FIS and FLN, in the year that governments around the world fell.

The FIS responded to the military oppression with a campaign of terrorism, both against the military and against foreigners who the FIS was certain were involved in this injustice. The FIS assassinated Boudiaff in June 1992; the military easily replaced him with Ali Kafi, who in turn was quickly replaced by a 5-member presidential High Council. In 1994, the Council named Algeria’s defence minister Liamine Zeroual as interim president of Algeria for a 3-year term, allowing him to "negotiate" with the FIS, FLN, and 3 other groups to give up their fight and negotiate terms of surrender. These negotiations led to elections in 1995, controlled and supervised by the military who claimed they were open and multi candidate – but were boycotted by the FIS. President Liamine Zeroual won the election, while the FIS continued it’s terrorism. On 7th December 1996, President Liamine Zeroual then signed new constitutional reforms which banned political parties that are formed on the basis of religion or language. These reforms led to an escalation of violence, with wide spread massacres and atrocities being committed by both sides.

On 15th April 1999, Algeria held elections which were won by Abdelaziz Bouteflika, a former foreign minister who has the support of the army. The elections were held amid allegations of fraud – six candidates with drew from the elections in protest. Though "ammnesty" was granted to the FIS in 2000, the civil war continues to this day, while the ethnic minority Berbers are just beginning their struggle for emancipation, and mainstream unions are joining them with frequent general strikes.

A Stubborn Fidelity, by Pierre Vidal-Naquet 1986.

Two Open Letters, from Djamila Bouhired, 2009.

The Algerian Communist Party, by Mitchell Abidor

Links: Algeria Watch: An excellent resource site for Algerian Material.

See also the Documents section. In français. (also available in Deutsch)

Battle of Algiers: from Rialto Pictures