Vindication of the “Guardian’s” Doctrines Respecting

the Rights of Capital and Labour

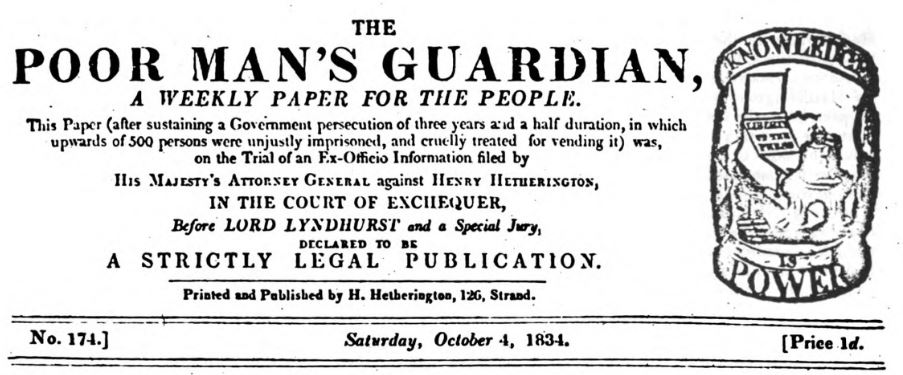

The Poor Man's Guardian. 1834

Source: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015013160968;

Written: by James Bronterre O'Brien, editor of “Poor Man’s Guardian” (‘editor’), in response to a letter written by someone with the pen name “Common Sense”;

First Published: in 1834, in The Guardian.

Friends, Brethren, and Fellow-Countrymen,

We publish to-day a letter signed “Common Sense,” which claims your especial attention. It is the production of a highly-gifted friend of the working classes – of one, too, who is a working man himself, and consequently has a personal but honourable interest in the present struggle between labour and capital. Before, however, we remark on this letter, the writer must permit us to take him to task upon the first paragraph of it, which is anything but complimentary to ourselves.

“If there be,” he says, “any one thing in which we have always thought the ‘Guardian’ has betrayed a species of dishonesty, it has been the very circumstance of its not sufficiently enforcing this identical fact – namely, that capital and labour, or that the interests of capitalists and workmen, are diametrically opposed to each other; and this apparent dishonesty of the ‘Guardian’ I have always attributed to the fact that the proprietor of the ‘Guardian’ is, in some measure, a capitalist himself.”

This is a poor compliment to the Proprietor of the ‘Guardian,’ and a still poorer one to the Editor. It supposes the former to be no better than any of the numerous depredators who “grind the faces of the poor,” and the latter to be a mercenary wretch, who writes whatever the Proprietor bids him. How “Common Sense,” who knows both the Proprietor and the Editor, could have formed this opinion, we are at a loss to conjecture, for we defy him, or any other of our readers, to point out any rational grounds to justify such a belief.

Let “Common Sense” take a retrospect of our former publications – let him only revert to the back numbers of the ‘Guardian’ or ‘Destructive’ – let him consult these, and then ask himself what other publication, stamped or unstamped, has ever been so explicit and uncompromising as we have been on the subject of capital. His answer must be, “There is none!” He must admit that if we have not stood alone, we have been at least the most ardent and untiring of all the enemies that capital has had to contend with.

Indeed, we have pursued the subject almost usque ad nauseam. Week after week, and in number after number, have we expatiated on the frauds of capital. With the certainty of offending many, and the risk of tiring all, we reverted again and again to the subject. Our correspondent must surely recollect how we exposed most of the great London houses in the “Destructive” and “People’s Conservative.” He must remember our exertions at the time the Linen Drapers’ Association was formed – how we espoused the cause of the assistants against the gormandizing capitalists, who wanted (under a show of benevolence) to make degraded tools of them, and how it was mainly owing to our exposures that the capitalists had to renounce their aristocratic pretentions, and suffer the young men to form the institution on the basis of universal suffrage, annual elections, the vote by ballot, and no property qualifications. If “Common Sense” will revert to our writings of that period (some of which were subsequently republished as penny tracts), he will see reason to do us justice; or, if his reading of us has been even confined to the “Guardian,” the result must be the same, for we could point out at least fifty numbers of the latter, the main drift of which was to convince the Radicals that all reforms in Church and State which did not go to emancipate the labourer from the tyranny of capital would be useless, or worse than useless, to the working classes. This we have always stated to be the master-evil of society.

As to our correspondent’s suspicion arising from the fact of Mr. Hetherington’s being a capitalist himself, it is equally unworthy of the writer, or Mr. Hetherington, and of the Editor of this paper. Hetherington’s interests as a capitalist may or may not be distinct from those of the class for whom he publishes; but “Common Sense” knows little of the man if he supposes that any base motives of self-interest could make him a traitor to his conscience, or an apostate from the creed and practice of his life. Still less does he know of the Editor, if he supposes him capable of being a tool for such purpose. Mr. Hetherington is the proprietor of the “Guardian,” but not of the Editor’s conscience. And “Common Sense” may take our word for it, that were it possible for Hetherington to renounce, or even shrink from his principles, the writer of this would be as ready to denounce him, in a new publication, as the Proprietor would be now to cut all connexion with the Editor, were he for one instant to prostitute his columns to such unworthy ends. To this we will only add, that a man of less penetration than our correspondent ought to know that the same parties who were honest enough to publish his former letters could never be so dishonest as to merit his unworthy suspicion.

And now for the letter itself. We challenge the whole junta of little masters to answer it, – we challenge them to meet it by a single fact or argument that can stand its ground a moment before the plain logic of our correspondent. They must not plead want of leisure or opportunity: of the former they have more than our correspondent, who, as a working man, is forced to give almost all his time to get a living for his family; and so to opportunity, they have the same that he had, for our columns are as open to them as to him, not to speak of the stamped newspapers, which, though hermetically sealed against us, are ever at their service. But they dare not answer it! – they know that they could not. ‘Tis easy to denounce the “Guardian,” when the “Guardian” is not present to refute them. ‘Tis easy to make assertions about “rights of capital,” where there is none present to disprove them; but why do not these masters condescend to explain what those “rights” are, or how “capital” has acquired them? This would be the obviously honest course of proceeding; but to go on asserting that the rights of capital are identical with those of labour, or (as the more usual slang is) that “labour has its rights, and so has capital, and that they ought to be mutually respected,” without any fact or argument to sustain such assertions, is, to say the least, a sorry specimen of imbecile improbity.

With respect to our correspondent’s reasoning, it may be right, perhaps, to observe, that where he supposes a case for the sake of illustration, his words are not to be constructed literally, for this is unnecessary to his argument. For instance, when he supposes the shopkeeper or manufacturer to sell the produce of labour for twice the price they pay for it, he neither means to say that the profits of trade always average out this much, or that these profits go all exclusively to the manufacturer or shopkeeper. What he complains of is, that too much is taken from the producer, or too little given back to him, which may be the case as well where the profits are only 10 per cent. as where they average cent. per cent.; and, as to the parties who appropriate the remainder, it makes not a farthing difference to the producer whether the profit-hunter keeps the whole to himself or divides it with the landlord, parson, or any other description of plunderer. In either case it is taken from the labourer, of whose wages it should constitute a part, and that is all that really does concern him. In fact, what our correspondent means is, that every farthing which is kept back from the producer out of the sale of his produce, beyond what would be a fair remuneration for the time and skill of the capitalist, or distributor, is so much plunder taken from the people.

And this brings us to the question of “property,” which is now being actively canvassed in France and the United States of America. Men have been always ready enough to cry out for the security of property, and to pass the most sanguinary laws for its protection, but few have taken the trouble to inquire how property is generally acquired, much less how it ought to be acquired. Very little reflection, however, will show that this is even a more important question than the other. For if the interests of society demand that property should be protected after it is acquired (and this is the only reason advanced by its advocates), those interests are still more vitally concerned in the modes or processes by which property is acquired. Indeed, it is doubtful to us whether there would be any laws at all wanted to protect property, provided there were just laws in the first instance, to render the acquisition of it possible only by fair and honest means. But, as matters go now, nine-tenths, or perhaps ninety-nine parts in a hundred, of what is called property, is acquired by legalized plunder; and hence that eternal war of those who want against those who have, and all the sanguinary laws resorted by the latter for their protection.

If the means of acquiring property be, then, of such paramount importance, the question naturally arises, How ought property be acquirable? – or when can it be said to be honestly acquired? This is a question that has never yet been fairly answered in practice, but, until it shall be so answered, the world will continue as heretofore, a theatre of crime and misery; for as long as bad laws enable one man to appropriate the fruits of another’s labour (without yielding him an equivalent), so long must the injured parties be expected to resist and retaliate in the best way they can.

To determine how property can be legitimately acquired, the legislator should ever keep this in view – that it is the duty of all to contribute to society, as much as they take from it or consume: in other words, all men should be workers as well as spenders. When the Almighty planted the foundations of the world, he willed that man should be sustained by his labour: this is not only evidenced in the laws of nature, which ordain that there shall be no wealth where there is no industry, but also in the revealed Word, in which it is written that in the sweat of his face man shall eat his bread. Nor is there any reservation or qualification in favour of particular castes or persons: the law of nature knows no such distinctions, and revelations disowns them, since it has made no mention of them. Labour is, therefore, the pre-ordained lot of all.

But how is this divine law to become the practice of society, seeing that every man tries as far as he is able to appropriate his neighbour’s produce? We answer, there is but one way of doing it, – it is to establish Democracy, not only in the government, but throughout every industrial department of society. The monarchic principle has hitherto governed all establishments, local and general, and hence the monstrous inequalities of wealth and station we behold. Take a factory, for instance, and is not the proprietor of it a sort of petty monarch? Has he not a sort of absolute control over all the wealth produced in it, though he has not added one single particle of wealth? And does he not possess a more direct and immediate power of life or death over the hands employed in it than any regal monarch can be said to possess over his subjects. Undoubtedly he does. But is it right that he should possess this power. Is it right that one man should thus hold the lives of hundreds at his pleasure, or that he should be able to say to one man, “Stay, and accumulate for me upon my terms,” and to another, “Go and starve, for I don’t want your services?” No man will pretend it. The proprietor of a factory is no more than a director or manager. He does nothing but what a salaries agent of the concern could do as well, or better. Nay, he is often a mere sinecurist, who has no more to do with the concern than has a non-resident parson with the souls of his parishioners. They, both of them, employ others to do the work, and, provided they duly receive the profits, give themselves no further trouble. Now, surely if the hands in a factory, with a proper officer to direct them, can accumulate capital for a drone of this kind, they ought to be able to do the same for themselves.

If a bloated pluralist in Naples can cure souls in England through a hired curate, the devil is in it if the curate and parishioners could not manage the affair without him; and if a bloated capitalist can, by hiring a few hundred men, and a few managers to superintend, accumulate a mountain of capital for his own use, the devil is in it if the same men and the same superintendents could not accumulate the same capital for themselves. The wealth of a factory is solely the result of the labour and skill employed in it: to the proprietors of this skill and labour should the wealth belong. The superintendents of the concern should be mere agents appointed to conduct the business. They should be elected by the body at large, and paid their weekly wages like the rest of the men. These wages, as well as those of the men, should be regulated by the voice of a majority, according to the respective services of each; and to give the whole a just, as well as a concurrent, interest in the establishment, the profits should be divided among all in the like proportions at the winding up of the concern.

(To be continued in our next, when the subject shall be more minutely canvassed.)

October 4, 1834

To the Editor of the Poor Man’s Guardian

Sir, – I perceive by the public papers that the Little Masters, at their meeting on Monday week, at the Queen’s Arms Tavern, Red Lion square, denounced your statement in the “Poor Man’s Guardian” of the week previous, wherein you said that the interests of capital and labour are not the same; or, in other words, that the interests of capitalists and their workmen are not identical, but that they are opposed to each other! Now, if there be any one thing in which I have always thought the “Guardian” has betrayed a species of dishonesty, it has been the very circumstance of its not sufficiently enforcing this identical fact, namely, that capital and labour, or, that the interest of capitalists and their workmen are diametrically opposed to each other; and this apparent dishonesty of the “Guardian” I have always attributed to the fact, that the proprietor of the “Guardian” is, in some measure, a capitalist himself.

A Mr Robarts, and a Mr. Burden (two little masters), appear to have been the principal speakers who denounced your statement as being false. Win these two little capitalists undertake to shew us what it is that constitutes what is called capital, and likewise how this capital is acquired, before they again attempt to identify the interest of capitalists and their workmen? No, I will be bound they will not; and if they will, it will be done in much the same way as a Jew clothesman shews an old coat: before you have time to look at one part at will be twisted over and over a hundred times, so that if you look for an hour you will not be able to discover its defects, nor be any thing the wiser. Now I am one of that sort of folk who do not like any of this kind of twisting and shuffling. I like to hold a thing perfectly still, and look fairly at it, before I attempt to decide upon its merits or demerits, or its interests, or any thing else concerning it. Suppose, then, before we say any more about the interest of capital and labour, that I undertake to define what capital is, and likewise how capital is acquired, and then, perhaps, we shall be better able to understand whether its interest be identified with that of labour, or whether it be not. I shall have no twisting and shuffling; I shall hold Mr. Capital perfectly still till we see clearly what he is, even though he look as white and as confused as Cain, after he slew his brother Abel.

Well, then, capital consists of what, at the present day, is called property, no matter whether that property consists of money, houses, land, goods, or machines for making goods. All these things are called the property of somebody, and therefore they all constitute what is called capital in the hands or possession of somebody or other. Now, the question is, – how is this capital, or property, acquired? Let us see. A man must work fifty years, and receive forty shillings every week during that time, and live on nothing, to be enabled to accumulate five thousands pounds by his own industry. He may rest assured, therefore, that large masses of capital, or capital to any large extent, cannot be acquired by one’s own honest industry; because forty shillings a week is just three times as much as the average pay, wages, or income of the honest and industrious part of the community. How then is this capital acquired? Why, in this way: – capital in the hands of a shopkeeper is acquired by exorbitant profits (that is, by buying cheap and selling dear); – capital in the hands of a master-employer is acquired by employing a number of workmen, and instead of paying them little short of what they earn, he sends them home to their families with empty pockets, and keeps their earnings himself; (that is, be buys their labour cheap, like the shopkeeper, and sells it dear); – capital in the hands of a landowner was originally acquired by stealing the land from the rest of the community; and the present capital, called rent, is acquired by taking that money in the name of rent which ought to be paid to the agricultural labourers in the name of wages; – capital in the hands of a priest , or parson, is acquired by taking that money in the name of tithe which ought also to be paid to the labourers in the name of wages; – capital in the hands of a lawyer is acquired by receiving a part of the capital of other capitalists for settling the disputes about the capital they have acquired; in short, capital is acquired in all cases by imposing on the working people, by keeping their earnings and amassing it into capital, instead of paying it to them in the name of wages; in pain truth, capital is acquired by plundering the working people of their wages, or earnings, and therefore capital to any extent, and particularly without honest labour, is plunder.

Now, will this Mr. Rob-arts, and this Mr. Burden-on-the-arts – will these two little capitalists say, if a shopkeeper stocks his shop with goods to the amount of two hundred pounds, and afterwards sells one half of those goods for the same sum, and thereby amass the other half into capital, that his interest, and the interest of his customers (who pay just double what they ought to do for the goods), are identically the same? Will these two little capitalists say, if a workman takes his body into the market, as it is called, and sells it to them for four shillings a day, and they afterwards sell the produce of his body for eight shillings a day, that their interest, and the interest of this workman, are the same? Will they say that keeping his earnings and amassing it into capital for themselves and families, and paying his earnings to him for the comfort of himself and his family, are identically the same, and both parties have the same interest in both cases. If they will, why not pay all their workmen every shilling of what they earn and relinquish their desire to amass their earnings into capital? No, no, no, Mr. Editor, this side of the question won’t do. Mr. Rob-arts and Mr. Burden-on-the-arts will not agree to this. The interest of capital and labour are identical only when Mr. Capital is allowed to do as he likes, and take what he pleases.

If a workman receives four shillings for making an article, and his master, or capitalist, afterwards charges four shillings more on the same article in the name of profit, the price of that article (setting the materials aside), will be eight shillings; and if the same workman be desirous afterwards of buying this article for his own use, he can, with his four shillings of wages, obtain only one-half of it; whereas, on the contrary, if the workman was to receive seven shillings, and the master, or capitalist’s profit were only one shilling, the workman could obtain seven-eights of the same article for himself and family. Will Mr. Rob-arts and Mr. Burden-on-the-arts say that the interest of the capitalist and the workman in both these cases are the same? But Mr. Rob-arts and Mr. Burden-on-the-arts will say, perhaps, that they are builders of houses, and that their workmen do not buy houses, and therefore my examples are not applicable to them, or to their trade. God bless us, and keep us: they don’t buy houses! Well, but they hire houses, and if Mr. Rob-arts and Mr. Burden-on-the-arts charge as much in the name of profit for the building of a house as they pay their workmen for doing the work, the price of that house, as far as wages and profits are concerned, will be double what it would be without profits, and the owner, for whom the house is built, will charge his tenant double the amount of rent he would otherwise have done to recover the expence or charge of that profit, which the workman, or occupier, or whatever he may be, will have to pay, let his wages be ever so small; and therefore he has to pay an additional rent out of his low wages for his master’s profits. In short, he has to pay for his master’s profits in the shape of additional rent to another man. Is the interest of capitalists and their workmen in all these cases, or in any one of these cases the same? If they be, why did Mr. Rob-arts and Mr. Burden-on-the-arts meet to oppose the interest of other capitalists? It won’t do, it won’t do, Mr. Editor, the web is too flimsy; they are like the Roman Catholic priests, who declaim against tithe-capital, because the tithes are not in their possession. These men want the chance of robbing the workmen, instead of the large capitalists: this is their sole object. They have no sympathy whatever for the men, and this is the reason why, with one breath, or in one sentence, they condemn the influence of capital on those men, and yet assert that the interest of capital and labour are identically the same!

We can easily discover a motive then, in the name of selfishness, for these little capitalists, in their attacks upon you. But what shall we say of Mr. Wild, who represented himself to be an operative. This is a wild affair indeed. I can account for his conduct in no other way than that of downright ignorance; or otherwise that some Mr. Rob-arts, or Burden-on-the-arts, or some other little Burdensome capitalist, had taken him by the arm and led him to the meeting, and that he was wild enough to suppose that by succumbing to capitalists be should soon become a capitalist himself. Really, Sir, when one sees an operative, for whom you have fought through thick and thin, turn round upon you and denounce your efforts as false and mischievous, it is enough to make one exclaim with the old Grecian philosopher, when speaking of such people. “I know nothing that they approve,” said he, “and I approve of nothing that they know.”

However, let us not be too severe. Let us not suppose, because we have discovered one wild man amongst the operatives, that the great body of them are not more civilized and more enlightened. The very fact of their striking against the capitalists is a proof that they are more enlightened than Mr. Wild. I hope, therefore, you will continue to hold up the mirror of truth as high as you can reach, regardless of any wild man who may happen to be among the crowd, and if he cannot stand the reflection let him retire to the woods.

I am, Sir, yours respectfully.

Sept. 24th, 1831.

Common Sense.

Postscript. – These little capitalists complain that they shall be ruined by the big ones. But in this case, and the foregoing one about capital and the means of acquiring it, they have omitted to tell us what they mean by being ruined. I will therefore tell it for them. Well then, they mean, if they cannot get the contracts out of the hands of the big capitalists, that they shall be obliged to lay hold of the shovel, as the saying is; that is, that they shall be obliged to go to work and get their living by labour, like the workmen; and therefore they recommend these workmen to work for them for 4 shillings a day in preference to working for the large capitalists for 6 shillings, to save them from going to work, or from being ruined. This is what they mean by being ruined, and this is the sacrifice they ask for on the part of the workmen to save them from being ruined, as they call it. What dirty little dogs these little capitalists are. Why, if going to work constitute what they call ruin, then the workmen have been ruined ever since they were born, or ever since they have been able to work.

It is curious to observe the ideas which people attach to this word ruin. When speaking of a capitalist being ruined, one would suppose they meant he had broken both his legs, both his arms, or that he had become blind of both eyes; whereas they only mean that he is obliged to get his living by his own earnings, instead of living upon the earnings of other people. There are two hundred and eighty-four thousand little capitalists, and big capitalists, and others, who receive thirty millions a year, or two-thirds of all the government taxes, in the name of usury or interest for the money which they and their forefathers have squeezed out of the earnings of the working people and lent to the government. If these people had to go to work and soil their hands, instead of loitering about and receiving the earnings of the working people, of course, according to their acceptation of the word, they would be ruined. A father, having brought up his sons till they are fourteen or fifteen years of age, sets them to work for their living, instead of living, as heretofore, out of his earnings, and what is the consequence? Why, if we agreed with the little capitalists, and big capitalists, and other people of the same stamp, we should say that the boys are ruined beyond all cure. Now this sort of ruin is the only ruin which the working people ought to strive for as a relief from their own ruin; that is, that every man should earn his own living, instead of living on the earnings of other people.

But what do these little capitalists offer the workmen in return for this sacrifice of two shillings a day to prevent them from being ruined? They know the workmen want universal suffrage, or the right of assisting to make the laws; a circumstance which would soon set all things to right. Lord Durham says that these men have as great a right to have a share in making the laws as any other man in the kingdom. But do these little capitalists promise the workmen that they will assist them in acquiring this right; an object which they, in conjunction with the little shopkeepers, could accomplish at any election they chuse to fix upon? No, they will see the workman at the devil, and their families too, before they will promise, not to work, but even to speak, one word for them. The workmen then are as great a set of blockheads as ever rivetted a fetter upon their own limbs if they do not cut the connection with them, and suffer them to be ruined, unless they promise to use their influence with other little capitalists, and to vote for no member of Parliament who will not pledge himself to secure to every man his proper share in making the laws, and thereby a share in regulating the different institutions of the state.

C.S.

Friends, Brethren, and Fellow-Countrymen,

IN discussing last week the substance of property, we stated that the grand evil of society is, its allowing properly to be unfairly acquired. Most people, when they talk of the evils of property, complain of inequality in its distribution, or of the undue protection afforded to it by the Legislature. This is very foolish. It is like petting a child first, and then grumbling that he is spoilt. It is to the mode, or modes, of acquiring property we should look. If these be just and honest, it is certain there will be no large accumulations in the hands of individuals. If, on the other hand, these be founded upon injustice and usurpation, we must expect to see property distributed as it is now.

Be it observed, then, it is not of the amount of capital we complain, nor of the degree of protection afforded to it; these are faulty enough, but they are accidents, not principles. A man may possess but a very small fortune, and yet have come dishonestly by it; and a man with a very large fortune may have honestly acquired it. In either case it is not to the amount we look, but the mode in which it was acquired. In like manner, the protection given to property is, doubtless, an evil in its way, and a monstrous evil too, since it is often given at the expense of life and liberty, which are paramount rights; but, like the other, being only an accident in the system, it would be a waste of words to discuss it, so long as we permit the system itself. If property is unnaturally acquired, it will require unnatural means to protect it. Besides, it is with principles, not accidents, we profess to deal here.

Whether there ought to be such a thing as property at all has been a subject of much perplexity, and some of the best philosophers were of opinion that the world would go on happier without it. For our own part, we are free to confess ourselves of this school, though not without some important reservations. We believe, that if the word property had been never heard, or the idea never formed, mankind would be a far happier race than we find them; but having once got into the property-system, (and perhaps in the first instance unavoidably) it is questionable whether they will ever be wise enough to get out of it again. At all events, a community of property, if it exists, must be a voluntary association. It will not take place by force, nor yet by Act of Parliament; it must be the spontaneous work of a highly-enlightened people, acting under an entirely new state of public opinion. So far then as protection or encouragement would go, we are staunch co-operators; but we should have no man robbed by law, or otherwise, merely because another man or party thinks he would be happier without property than with it. If people choose to get into community let them do so, but there should be no compulsion – no foul play of any kind.

But, as we cannot get men to co-operate and live in common, the next best thing is – to enable them to acquire property fairly, and use it in the same way. As society works now, few acquire property fairly; it is almost all got by fraud, or force, or an admixture of both; a single glance at society must convince us of this; for wherever we turn, we see most wealth where there is least industry, and the greatest poverty with those who contribute most to the common stock. There is no getting over this: no sophistry can gild or smooth down a system that engenders such results. Property, to be fairly distributed, must take directly the opposite course; that is, those who contribute most to the common stock should possess most; those contributing in the next degree, should possess next most; and those not contributing at all should possess nothing at all, unless disabled by physical or other natural causes.

But how are we to have this just distribution, for there is no use talking of it unless the thing can be done? We answer, as we did before, by establishing the democratic principle in every department of society. Unless this is done, we shall never see a different state from the present; and, if it cannot be done, we see no alternative before us but death or bondage. At present the monarchic principle governs throughout society. We find it in every industrial department; we find it in the factory, in the workshop, in the counting-house, in the farm, in every branch and walk of life. Whatever relates to the distribution and production of wealth, and even to education and public morals, is governed by the monarchic principle. The rulers are in all these cases self-appointed, or (which is the same) appointed by persons having the same interest as themselves. The factory is governed by an autocrat, who is self-elected, and responsible to no one for the proceeds of the establishment. These proceeds are the sole result of the labour and skill of the hands employed: to these hands should the wealth, therefore, belong. But here the autocrat steps in, and says, “No; I am master of this concern. I was not appointed by you to organize and direct your industry; but you were commanded by me, under a penalty of starvation, to slave for me as you have slaved, and to take as much as I gave you, and no more. It is true all the capital I possess is the offspring of your industry, but what avails that since I am your lord and master,” &c.

And the same principle obtains in the counting-house and farm. In the former, whatever labour is done is done by the clerks and assistants, but the self-appointed monarch monopolizes all the proceeds. Nor are the actual labourers the only sufferers; the little monarchs who rule them in the first instance are themselves the slaves of a still direr despotism than their own: we mean that of the bankers and large capitalists. Upon these hangs their credit and very existence. An act they dare not do, a syllable they dare not utter, to displease these potentates. Nay, the wealth they have so unmercifully wrung out of their serfs in profits is still more unmercifully wrung from themselves by the all-ruling usurer. Not more than three days ago we saw a tradesman give a usurer a bonus of £20 for cashing an accommodation bill of three months – that is, the wretched borrower had to pay at the rate of 80 per cent. per annum for the loan of £100.!

And so it runs throughout society; the monarchic principle prevails in all, and, as a consequence, all are slaves except the few great capitalists. The wealth which the people produce, instead of being a source of enjoyment to them, becomes an instrument for oppression in the hands of their task-masters; so much so, indeed, that the fact is become notorious, that the more wealth the population shall produce in future, the greater will be their own privations and bondage; and for this plain reason, that it will merely go to increase the number and power of their task-masters.

Before the editor of the “Guardian'’ appeared as a writer, it was generally fancied by the people that the taxes were the main cause of their distress. This was a very foolish idea, but considering what very eminent men held that opinion, – considering too, that Paine and Cobbett were amongst its promulgators, it is not surprising the people believed it. Now, however, they are pretty well cured of the delusion. We have shewn them that the taxes are not as a feather in the scale in comparison with the whole of their burdens. We have shewn them the utter inadequacy of Cobbett’s propounded remedies to meet the evil. We have shewn them that, even if it were practicable to-morrow (which it is not) to go back to his standard of government expenditure, (that of 1792) we should be no better off than we are now. Indeed, a single fact is enough to prove this – it is, that Paine considered £10,000,000 of taxes to be absolute ruin in 1792, and made it the foundation of all his attacks on monarchy; and yet this expenditure, which Paine thought death and destruction, is demanded by Cobbett as a sovereign panacea. The Lord deliver us from our friends!

We shall conclude these remarks with the following strictures on capital, which we extract from a second letter of our worthy correspondent, “Common Sense.”

In your “Guardian” of the 27th ultimo, you asked what the rights of capital, or what the rights of capitalists are. I am not so presumptious as to suppose that I am infallible in all I say, but I will venture to give an opinion upon this point. In plain honesty, then, and impartial justice, capitalists have no rights whatever beyond other people. No capitalist has a right to appropriate the earnings of other people to his own private use; and, if he does, it is plunder. But as working men in general, probably, if left to their own discretion, would not build themselves houses and warehouses, and provide such other things as are provided at present, we may concede to a capitalist or master the right to retain as much of the earnings of his workmen as will enable him to build those houses, &c, and likewise the right of letting those houses, and so on, to his workmen, and of demanding as much rent for them, and profit for his warehouses and machines, as will keep those things in repair. But he has no right to any more than will effect that purpose. He has no right to retain as much of their earnings as will enable him to provide himself with coaches, curricles, pleasure-horses, hounds, servants, or as will enable him to go to plays, routs, and frolics, nor to live more sumptuously than his men; nor has he any right to demand as much rent or profit on his houses, warehouses, &c., beyond the requisite sum necessary to keep them in repair, as will enable him to resort to those extravagancies. All those extravagancies are obtained by robbing his workmen of their earnings, or of extorting from them more rent than he is entitled to. The proper guide, then, for all working men is this: -

They should observe whether their master indulges in any extravagance of which they are not enabled to obtain a proportional share; or whether he keeps servants to do those household duties in his family which their wives are obliged to do in their families, and if he does, they may rest assured that they are imposed upon, and he could pay them higher wages if he chuses. All those extravagancies and servants are paid for out of his workmens’ earnings, and is so much fraud upon them. His workmen are more entitled to, and could consume as fair a share of every thing they produce, as he and his family can, were he not to withhold their earnings. The same observations are applicable to shopkeepers, and to all other capitalists.

But if we grant to a capitalist the right to demand rent on his houses, &c. for the purpose of keeping them in repair, what shall we say of the rights of a money-capitalist? Money requires no repair, or what is next to nothing. The wear and tear of money is only ten per cent. per century; that is, ten pounds wear on a hundred pounds sterling, in a hundred years, which is two shillings on a hundred pounds sterling in one year. What then shall we say of a money-capitalist, who lends a hundred pounds to another capitalist or master, upon the condition that he stops one hundred shillings a year out of the earnings of his workmen to give to him for the use of that hundred pounds, or fifty times as much as is required to keep it in repair? What shall we say to this? Why that it exceeds everything else that bears the name of fraud. Rent and tithe on land, however, are worse still, for no part of that whatever is appropriated to the repair of the land. But there is something else far worse still; but that I will not name, lest it should drive the injured party mad.

At the time of William Pitt, or 40 years ago, the whole of the money and other capital of the kingdom was reckoned at thirteen hundred millions. At the present time it is upwards of three thousand millions; so that here is seventeen hundred millions of capital reared out of the people’s earnings in 40 years, and upon which they are obliged to give up, year by year, much more than is necessary to keep it in repair, the overplus of which is spent principally in the shape of extravagance; and this is an addition to what they gave up at the time I have named. Capital has already swallowed up every thing in Ireland, and it is no difficult matter to see that it will soon do the same here. These are my opinions on what is called the rights of capital.

Common Sense