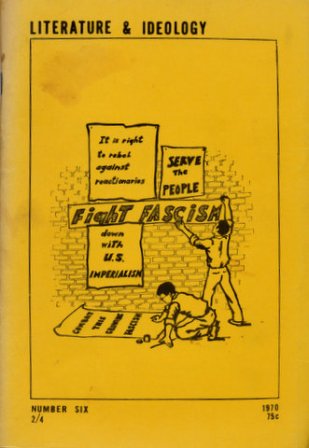

First Published: Literature & Ideology, No. 6, 1970.

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

The petty bourgeoisie is not a counter-revolutionary class per se, even though some sections of it do work for U. S. imperialism. Masses of the petty bourgeoisie support the sentiment for change and are actively participating in the mass democratic struggles against the fascist policies of oppression at home and aggression abroad. In order to combat the growing revolutionary sentiment of the American people, U.S. imperialists sponsor agents from within the most opportunist sections of petty bourgeoisie and dress them up as “revolutionaries” of the new generation. Monopoly capitalist publishing houses, national television networks and popular weeklies give publicity to these petty-bourgeois self-seeking and self-promoting opportunists and careerists who advocate the politics of ecstatic self-indulgence and drug-induced “inferior illumination” and withdrawal into the self. The individuals who participate in this kind of activity are called the “New Man,” their minor emotional disorientations the “New Sensibility.” Their aim is to create the “Alternative Society” in the midst of U.S. imperialist culture. Whatever they may be indulging in at any moment is labelled “The Movement.”

The objective historical role of “The Movement” is to hold high the banner of self-centred, decadent and parasitic living and to glorify the bliss of “pleasurable idleness.” Jerry Rubin, Abbie Hoffman and Norman Mailer are three of the popular proponents of “The Movement.” They belong to the group of mystics and culture-heroes which includes T. Leary, Allen Watts, Allen Ginsberg and other prophets of acid, drug, rock and mind expansion. They are irrational and egocentric in their outlook and want to live a passive but exciting life of consuming everything produced by U.S. industry. Jerry Rubin defines “The Movement” in his Do It:

The movement is a school and its teachers are the Fugs/Dylan/Beatles/Ginsberg/mass media/hippies/ students fighting cops in Berkeley/blood on draft records/sit-ins/jail.

Abbie Hoffman explains his notion of “The Movement” in Revolution for the Hell of It:

Fun. I think fun and leisure are great. I don’t like the concept of a movement built on sacrifice, dedication, responsibility, anger, frustration and guilt. All those down things. I would say. Look, you want to have more fun, you want to get laid more, you want to turn on with friends, you want an outlet for your creativity, then get out of school, quit your job. Come on out and help build and defend the society you want. Stop trying to organize everybody but yourself. Begin to live your vision.

In Armies of the Night Norman Mailer blesses “The Movement” as the pursuit of a vision:

An extraordinary multiplication of the romantic, but it was not Rubin’s apocalyptic vision alone–it had been seen before by men so vastly different (but for the consonants of their name) as Castro, Cortes, and Christ–it was the collective vision now of the drug-illumined and revolutionary young of the American middle class.

He recommends “The Movement” for its “belief” in “the revelatory mystery of the happening where you did not know what was going to happen next; that was what was good about it.”

“The Movement” does its best to make things exciting for its petty-bourgeois seekers of fun. The fun is based on the gratification and flattery of the self. Herbert Marcuse, R.D. Laing and many others have stressed recently the idea of the ego as the core of experience. R. D. Laing says in The Politics of Experience that the “ego” is “the instrument of living in this world.” And he praises “transcendental experience,” for “the outer divorced from any illumination from the inner is in a state of darkness. We are in an age of darkness.” And Norman Mailer says in Cannibals and Christians:

So long as it is a healthy soul, its nourishment comes from growth and victory, from exploration, from conquest, from pomp and pageant and triumph, from glory.

Is this sufficiently simple for you? It lives for stimulation, for pleasure. It abhors defeat. Its nature is to become more than it is.

Translated into political action, Mailer’s philosophy produces Abbie Hoffman’s excitement about the revolution, when the political activity takes the form of mind expansion:

Revolution for the Hell of It? Why not? It’s all a bunch of phony words anyway. Once one has experienced LSD, existential revolution, fought the intellectual game-playing of the individual in society, of one’s identity, one realizes that action is the only reality; not only reality but morality as well. One learns reality is a subjective experience. It exists in my head. I am the Revolution.

Says Jerry Rubin in Do It:

That is guerrilla war in Amerika: everyone doing his own thing, a symphony of varied styles, rebellion for every member of the family, each to his own alienation.

The message is clear: Follow your own whims for self-gratification and cultivate your ego.

The best example of the cultivation of the ego can be seen in these counter-revolutionaries’ hatred for ideology. Ideology, they say, is a disease. The ideal situation, according to Jerry Rubin, the birth of a party without an ideology, can be found in this characterization of the “Yippie” movement:

We got very stoned so we could look at the problem logically:

It’s a youth revolution. Gimme a “Y.”

It’s an international revolution. Gimme an “I.”

It’s people trying to have meaning, fun, ecstasy in their lives–a party.

Gimme a “P.”

Whattaya got?

Youth International Party.

Paul Krassner jumped to his feet and shouted: “YIPPIE! We’re yippies!” A movement was born.

These petty bourgeois make a mystery of experience and select for admiration only the totally personal and incommunicable in an individual’s sense of his own life. Mailer’s audience consists of those who have inner experience but no ideology, as he himself explains in Cannibals and Christians:

I suppose it’s that audience which has no tradition by which to measure their experience but the intensity and clarity of their inner lives. That’s the audience I’d like to be good enough to write for.

“The Intensity” Mailer talks about is “The Movement’s” euphemism for a rejection of any clear and scientific analysis of the political struggle for defeating U. S. imperialism.

By and large, “The Movement” is anti-intellectual, anti-rational, and opposed to class struggle in the ideological field. The “Movement” activists love confusion and ignorance of history and let the ego express itself in thousands of different forms. It would be insane to undertake a project to make sense of the publications and speeches of “The Movement,” but it would be wrong to argue that “The Movement” is inconsistent. It consistently serves the class interest of U.S. imperialism. “The Movement” makes constant efforts to put itself in leading positions with the aim of persuading people that “happenings,” egoistic theatrics or obscenities should be substituted for anti-imperialist struggles. “The Movement” may change its stage props in the course of a year, but its basic class role is always the same.

“The Movement” consists of a small band of “leaders” who reach the public through the courtesy of pro-imperialist media like the Guardian and the New Yorker. These leaders specialize in self-dramatization and “heroic” clowning. Jerry Rubin explains how to carry on class struggle in the classroom in Do It:

Marvin Garson takes off his shirt and begins tongue-kissing with his chick Charlie. I rip off my shirt and start soul-kissing with Nancy.

There we are in the middle of the class, shirts off, kissing, feeling each other up and smoking pot.

Abbie Hoffman glorifies himself by claiming that he has been a: drug salesman, ghetto organizer, campaign coordinator (peace campaign of Stuart Hughes and Thomas Adams, both in Massachusetts), SNCC field worker, movie theatre manager, grinder in an airplane factory, camp counselor, and cook. Mailer has carved a career and a philosophy for himself out of self-dramatization. He declares in “The White Negro” (Dissent, 1957) that the greatest question facing heroes like himself who believe in excitement and ecstasy is how to live with death:

It is on this bleak scene that a phenomenon has appeared: the American existentialist–the hipster, the man who knows that if our collective condition is to live with instant death. . . why then the only life-giving answer is to accept the terms of death, to live with death as immediate danger, to divorce oneself from society, to exist without roots, to set out on an uncharted journey into the rebellious imperatives of the self.

Mailer has called the life of the hipster “existential politics.” It is the politics of class-collaborationist self-dramatization.

“The Movement” believes in heroes and despises the masses; it believes in personalities and despises ideologies. Mailer has written in Presidential Papers:

Existential politics is rooted in the concept of the hero, it would argue that the hero is the one kind of man who never developed by accident, that a hero is a consecutive set of brave and witty self-creations.

Existential politics, however, derives not from politics as a prime phenomenon, but from existentialism. So it begins with the separate notion that we live out our lives wandering among mysteries, and can construct the few hypotheses by which we guide ourselves only by drawing into ourselves the instinctive logic our inner voice tells us is true to the relations between mysteries. The separate mysteries we may never seize, but to appropriate meaning from the relationship is possible.

Personality, heroism, mystery, instinctive logic: all these words occur frequently in the writings of “The Movement” and characterize its class role.

All these works occurred frequently also in the speeches and books of Adolf Hitler who believed in heroes and despised the masses and who believed in personalities and despised ideologies. Hitler said in Mein Kampf:

A philosophy of life which endeavours to reject the democratic mass idea and give this earth to the best people–that is, the highest humanity–must logically obey the same aristocratic principle within this people and make sure that the leadership and the highest influence in this people fall to the best minds. Thus, it builds, not upon the idea of the majority, but upon the idea of personality.

Hitler promised “to place thinking individuals above the masses, thus subordinating the latter to the former.” He spoke of the broad masses in these words:

The broad masses are only a piece of Nature and their sentiment does not understand the mutual handshake of people who claim that they want the opposite things. What they desire is the victory of the stronger and the destruction of the weak or his unconditional subjection.

This condemnation of the masses and a faith in the superiority of its own heroes is the essence of the fascist ideology of the self, propagated by “The Movement.”

A movement based on heroes and personalities is a fascist movement. It must pretend that it serves the interests of the people and must appropriate revolutionary language for counter-revolutionary purposes. But “The Movement” does not have any faith in the people: it hates “the oppressed” “for not fighting decisively to end their own oppression.” The most common form of anti-people propaganda is the stress on the generation gap as the basis of the revolution. The older are the enemy of the younger people, because they suppress adventure. Says Jerry Rubin: “Generational war cuts across class and race lines and brings the revolution into every living room.” The new generation is in possession of a new consciousness which is not available to the broad masses of people. Rubin sings praises of the new consciousness:

Instead of talking about communism, people were beginning to live communism.

The fragmented life of capitalist Amerika–the separation between work and play, school and fun. property and freedom–was reconstituted by the joyous celebrants.

Neither the civil rights movement, the Free Speech Movement or the antiwar movement achieved its stated goals. They led to deeper discoveries–that revolution did not mean the end of the war or the end of racism. Revolution meant the creation of new men and women.

Mailer attests to the existence of the new generation in Armies of the Night:

The new generation believed in technology more than any before it, but the generation also believed in LSD, in witches, in tribal knowledge, in orgy, and revolution.

To take part in the new politics of “The Movement” is “to partake of Mystery.” The name of the new generation is “Woodstock Nation.” Hoffman points out the way “to partake of Mystery”: “It’s only when you get to the End of Reason can you begin to enter WOODSTOCK NATION. It’s only when you cease to have motives at all can you comprehend the magnitude of the event.”

Words like “Mystery,” “blood,” “impulse,” and “myth” appeal to “The Movement” as much as they did to Hitler and his storm-troopers. “Act first. Analyze later. Impulse– not theory–makes the great leap forward,” says Rubin.

Abbie Hoffman says, “I trust my impulses. I find the less I try to think through a situation, the better it comes off.” Mailer babbles about the Mystery of Christ as an explanation of the American aggression in Vietnam: in Armies of the Night he announces that the love of the Mystery of Christ and the love of no Mystery whatsoever “brought the country to a slate of suppressed schizophrenia so deep that the foul brutalities of the war in Vietnam were the only temporary cure possible for the condition. ...” Anti-people propaganda of this sort informs the writings of “The Movement” and is used by Mailer in The Presidential Papers to predict the appearance of a Hitler in America:

Why do you think people loved Hitler in Germany? Because they all secretly wished to get hysterical and stomp on things and scream and shout and rip things up and kill–tear people apart. Hitler pretended to offer them that. ... If America gets as sick as Germany was before Hitler came in, we’ll have our Hitler. One way or another, we’ll have our Hitler.

Reading Mailer, Hoffman and Rubin, we find that it is these leaders of “The Movement” who are hysterical. Then combine brutality with a flimsy idealism; they scream; what they want is that a Hitler should come and save them. Hence they talk about the myth–the myth which brought Hitler to power in defence of disintegrating German capital. Rubin’s mythical vision has elements of a Hitlerite ecstasy: “The Festival of Life vs. the Convention of Death: a morality play, religious theater, involving elemental human emotions–future and past; youth and age; love and hate; good and evil; hope and despair. Yippies and Democrats.” The elemental human emotions Rubin glamourizes belong to the “Beast” on whose back, according to Mailer, Hitler rode to power. “The Beast” is what many “Movement” leaders want to be and try their best to be. They conceive of their public and private lives as beast-like heroism.

An insatiable ambition of the leaders of “The Movement” is to be able to do whatever they want to do. Hoffman goes on with his proposition of “fun and games”: “People can do whatever they want. They can begin to live the revolution if only within a confined area.” This confined area for the “Beast” is evidently the vagina; Hoffman believes that “people should fuck all the time, anytime, whomever they wish. ...” “The Movement” works for the overthrow of civilization and a return to the animal “Alternative Society.” Jerry Rubin puts forward the ideals of the “Alternative Society” in Do It:

We are liberating the city, turning the streets into our living rooms. We live, work, eat, play and sleep together with our friends on the streets. Power is our ability to stand on a street corner and do nothing. We are creating youth ghettos in every city, luring into the streets everyone who is bored at home, school, or work. And everyone is looking for “something to do.”

For us empty pockets means liberation – from draft cards, checkbooks, credit cards, registration papers–we are close to our naked bodies.

These petty-bourgeois self-promoters imagine that people’s lives are vacant, depleted, meaningless and dull, and that they need to be returned to life through the agency of an “Alternative Society.” The class collaboration in this argument is that U. S. imperialism cannot be destroyed and that “The Movement” should function as an oasis in the deserts of an “affluent” culture. But this does not reveal the full extent of the reactionary character of “Alternative Society.” “Alternative Society” is an epitome of the most degenerate, parasitic and decadent features of U. S. imperialist culture. The American people hold “The Movement”, in utter contempt. Progressive Americans see a connection between one’s social practice and one’s consciousness and have never accepted the reactionary concept of an “Alternative Culture.”

“The Movement” leadership reduces political struggles to the whims of its own ego and personality, to the needs of its own selfish desires, and to a parasitic way of life. The leaders of “The Movement” hate the broad masses of people and slander them every day. Through it all shines the egomania of “the most important figures on the N. Y. Hippie Scene.” Hoffman writes, “One learns reality is a subjective experience. It exists in my head. I am the Revolution.” Bourgeois egoism is rooted in the monopoly capitalist relations of production and will vanish with the destruction of U.S. imperialism. The “stars” of “The Movement” will shine as long as there is national television and mass media owned by monopoly capital. Once the American people destroy bourgeois relations of production, these “stars” will disappear forever.