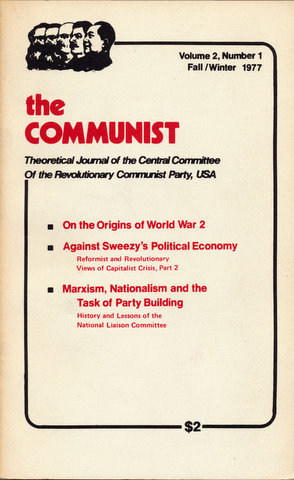

First Published: The Communist, Theoretical Journal of the Central Committee of the Revolutionary Communist Party, USA, Vol. 2, No. 1, Fall/Winter 1977.

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

The following article was written by a former leader of the Black Workers Congress (BWC) and the Revolutionary Workers Congress (RWC), the most significant of the organizations that survived a series of splits within the BWC, and the only one of the offshoots of the BWC to make any real attempt to actually apply Marxism-Leninism, Mao Tsetung Thought to concrete struggle and on this basis to link up with and help build the mass movement. In recent months, summing up the lessons, both positive and negative, of their past experience and reaching agreement with the line of the Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP), many members of the RWC have, in accordance with the Constitution of the RCP, joined its ranks. (In the course of this the RWC itself dissolved.) The author was a member of the National Liaison Committee, whose history is summarized below–Ed.

The degeneration and disintegration in late 1973 and after of the Black Workers Congress and another organization with which it was closely allied, the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Workers Organization (PRRWO) was the result of a retreat by these organizations away from Marxism-Leninism, Mao Tsetung Thought and into nationalism and other forms of bourgeois ideology which were closely linked to this nationalist outlook–though all of this was put forth in the guise of Marxism-Leninism, Mao Tsetung Thought. This turn toward opportunism resulted in a split between the BWC and the PRRWO on the one hand and the Revolutionary Union (RU) on the other, and caused the breakup of the National Liaison Committee (NLC) which had been built by these three organizations and served for over a year in 1972-73 as a vehicle for building toward the single Party of the U.S. working class and carrying out joint mass work with that goal in mind (for a time, another organization involved in the NLC was I Wor Kuen, about which more shortly).

Over the past several years a good deal has been said and written about the National Liaison Committee, most of it inaccurate gossip and subjective summation by people and groups who were not involved in it and/or whose ideological and political line prevents them from making a scientific analysis. For this reason, and most of all because the real history of the NLC and the line struggles which led to its breakup hold valuable lessons for the revolutionary movement today, it is important to sum up the actual development of the Liaison Committee and the forces and struggles within it.

In the summer of 1972, a major advance was made by Marxist-Leninist forces in the U.S., particularly towards the creation of a multinational revolutionary communist Party. This was represented by the formation of the National Liaison Committee, marked by the coming together of the Black Workers Congress, organized in 1970, the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Workers Organization, originally (1969-72) the Young Lords Party (YLP), and the Revolutionary Union, formed in 1968.

The BWC and PRRWO had their roots in the left wing or radical elements of the struggle of the oppressed nationalities. The makeup of these organizations was primarily students, revolutionary intellectuals and youth turned political activists. There were some workers, including from basic industry, particularly in the case of the BWC which had developed in part out of the thrust of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, a Detroit-centered organization which had built political organization among Black workers in the late ’60s.

The League was particularly noted for its development of the Revolutionary Union Movements–the most noted of these groups being Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM). The League greatly influenced and inspired the radical wing of the Black liberation movement and the entire revolutionary movement in those years, particularly in the wake of the degeneration of the Black Panther Party. For a time the League had a direct organizational relationship with the BWC until 1972, when a split occurred between the two groups.

To a large degree the BWC was composed of former “movement activists” from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), revolutionary intellectuals from the League, students who were turning towards Marxism-Leninism, and a smaller number of workers out of the Black workers caucus movement of the late ’60s. Among the principal strengths of the early BWC–and this was perhaps even more the case for the YLP-PRRWO–were these attempts to link up with the actual mass struggle of the people.

However, particularly in the early years of BWC (and the same is true of PRRWO) there was a tendency to downplay or deny altogether the revolutionary role and potential of white workers and to hold that Black people and “third world people” in the U.S. could make revolution in this country, in alliance with other liberation movements around the world but without the rest of the working class–or at least without white workers as a group. This was characteristic of the movement of the oppressed nationalities and the revolutionary movement generally in those times which BWC and PRRWO shared to a large extent.

The BWC in particular tried to unite with and develop the growing Black workers struggle–attempting to organize “RUM”-type (Revolutionary Union Movement) organizations from Los Angeles to New York, from Birmingham to Buffalo, from Detroit to New Orleans. BWC also played an active role in prison struggles through the Harriet Tubman prison movement which it led.

At the time of the Attica uprising in 1971 the BWC in coordination with the Harriet Tubman prison movement held significant mass demonstrations rallying masses in the Black communities in support of the prisoners’ demands.

In Detroit the BWC linked the Attica struggle with the stop and kill policy of the police under the name of STRESS, and organized a demonstration of 10,000 Black people in that city. In Buffalo it organized the largest demonstration in the history of the Black community there, bringing out over 4000 Black people. It built struggle against the war in Vietnam, and organized a Black Workers Freedom Convention which was attended by nearly 500 Black and other “third world” workers.

PRRWO was composed of students, a very large number of unemployed youth and a small number of workers. PRRWO had evolved out of the YLP; a major influence in the development of the YLP was the Black Panther Party–hence YLP’s early heavy emphasis on the ”lumpenproletariat as the vanguard.”

YLP-PRRWO had strong ties, even significant influence, among the Puerto Rican masses, especially in New York City, based on its leadership in the mass struggle. In the early years of YLP, even with its “lumpen vanguard” line, it had organized the Health Revolutionary Unity Movement, an organization of health workers which developed out of the struggle against proposed layoffs and cutbacks in services in the city hospitals of New York. Later they led the takeover of a large church in Spanish Harlem, turning it into a center where masses in the community received necessities and education in the basically revolutionary principles of the YLP. Hundreds of people were mobilized in this struggle.

The Lords set up health and breakfast programs in the church. They led numerous struggles against police brutality, bad housing and welfare, and played an important role in raising the issue of independence for Puerto Rico.

The RU was a multinational organization, and had been so almost from the start. It was true that, when the RU was first formed in the San Francisco Bay Area, it was composed almost entirely of white youth of student origin, most of whom had been active in building support for the struggle of the oppressed nationalities, the antiwar movement, the student movement, community organizing or all of these. A small number of veteran communists who had left the CPUSA after its revisionist betrayal played an important role in the RU’s formation. It was also true that the birth of the RU occurred primarily as a result of the struggles of the oppressed nationalities in this country.

The RU began directing its main activity to the working class and its members began rooting themselves in industrial work–an orientation and line that was greatly strengthened by an ideological struggle in the RU in late 1970-early 1971 against infantile adventurism and terrorism.

As the RU’s work developed it made ties with a number of white and oppressed nationalities workers who, as they became revolutionary oriented, joined the ranks of the RU.

The RU had significant influence on the antiwar movement and the youth and student movement generally, helping to develop it in a more consistently anti-imperialist direction. The RU did much to spread Marxism-Leninism among revolutionary-minded people, making many contributions in this regard through developing political line and carrying on ideological struggle over important questions facing the movement–the working class as the leading and decisive class in making revolution in U.S. society, the united front strategy, the correct line on the Black national question, the women question, the nature of the Soviet Union and others.

From its beginning the RU carried on hard-hitting polemics against erroneous trends in the movement, playing a big part in exposing many incorrect lines which still had popular currency and summing up scientifically a number of opportunist lines that were hated, but not deeply understood by many people. It took on anarchism and revisionism as well as Trotskyism and upheld and explained Marxism-Leninism, Mao Tsetung Thought and its basic application to the U.S. in opposition to these bourgeois lines within the movement.

In particular the RU struck hammer blows at the Progressive Labor Party (PLP), especially as the struggle against its line was coming to a head within Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) in 1969. At that time PLP claimed to uphold Mao Tsetung and China but actually promoted Trotskyism–denouncing the Vietnamese people for not fighting immediately for socialism; attacking the Black liberation struggle in the U.S. because it was nationalist not socialist and, PLP claimed, “all nationalism is reactionary”; denouncing the student movement as useless since it did not make its main focus linking up with workers in economic struggles, etc. The RU showed how PL’s line was in fact a perversion of and objectively an attack on Marxism-Leninism, Mao Tsetung Thought. This inspired many revolutionaries among the youth and students in particular to take up Marxism-Leninism, Mao Tsetung Thought and provided a revolutionary alternative not only to PLP’s Trotskyism but also to the two main tendencies within the student movement opposed to PLP at that time–the adventurism of the Weathermen and the even less justifiable stereotyped, stagnant and reformist “Marxism” and petty promoterism of forces clustered around Mike Klonsky (now head of the Communist Party–Marxist-Leninist).

The RU upheld the Black Panther Party (BPP) when it was a leading revolutionary force, building support and defense for it, especially with the growing violent attacks by the state on the Panthers. At the same time, while not engaging in open polemics against the BPP or incorrect aspects of its line, the RU carried on principled ideological struggle with the Panthers and popularized the understanding that the working class and working class ideology are the leading force in the revolutionary movement.

The RU not only carried on ideological struggle about the revolutionary role of the working class but initiated communist work in the working class itself, linking up with strikes and spreading revolutionary ideas in connection with workers struggles. All this had a big impact on the revolutionary movement and represented an important step in merging communism with the workers movement.

For a time I Wor Kuen (IWK), an Asian organization, was a part of the NLC–until it discovered it could no longer dodge ideological struggle and the carrying out of common work particularly among the industrial proletariat. IWK then fled like a vampire from a cross.

IWK’s development was quite the opposite of BWC, PRRWO and RU. It suffices to say IWK did not develop out of any particular mass struggle nor did it play any real role in linking up with mass struggle. Where it did join it more often than not played a backward role. IWK used as its principal cover–or more to the point, its capital–the fact that they were members of oppressed nationalities, and when it became fashionable to call themselves Marxist-Leninist they did so, only, however, to oppose Marxism-Leninism.

It sometimes happens as a section of the movement turns to Marxism-Leninism for honest reason, some who have in fact based their careers on attacking Marxism-Leninism suddenly take up the banner of Marxism-Leninism only to oppose and attack it from another angle.

So much for IWK. Back to the NLC. At its inception the NLC set for itself two basic tasks: common work and ideological struggle, that is, the linking up with the actual mass struggle of the American people especially the working class and the building of a new communist Party through forging a unified ideological and political line.

The NLC was formed based on the recognition that in the U.S. there is only one working class, a single multinational proletariat, and this multinational proletariat, especially the industrial proletariat, is the main and leading force of the revolution. The NLC was united around the need to build the Party of the proletariat to act as its vanguard at the earliest time in accordance with placing ideological and political line in the forefront and on the basis of establishing deeper ties with the masses, especially the working class. Further principles of unity of the committee were upholding Marxism-Leninism, Mao Tsetung Thought and opposition to revisionism and Trotskyism.

The NLC started with this basic level of unity and in roughly a year BWC and PRRWO had come to a higher level of unity with the RU, reaching essential agreement on Party building, the trade union question, the united front as the basic strategy for revolution, the analysis of the Black national question, and the woman question.

A charge made by some opportunists is that the NLC was simply “negotiations at the top.” The real fact of the matter was the Liaison Committee was far from this. There was the National Liaison Committee, which was composed of representatives from each organization; in addition, in each city where at least two of the organizations existed a local Liaison Committee was established.

While upholding the democratic centralism of the organizations in the NLC, joint work was carried out on the closest political and organizational unity, on a national and local scale. On the basis of discussion within and between the three organizations and within certain limits, the National Liaison Committee discussed priorities of mass work, nationally mapped out plans to unfold such work, struggled over the line and policy of work and later summed up the work.

On the local level a similar process was carried out. When comrades from the organizations which made up the NLC found themselves in the same work place, or the same general industries, or same area of mass work, work teams were set up. In one city commissions were established to give overall guidance to almost every major area of work. During the period of the NLC’s existence, a city-wide hospital organization was built in New York; in Detroit the organizations jointly took up building of a rank and file committee around the ’73 auto contract.

The NLC attempted to provide some leadership for the antiwar movement, and to particularly involve workers and oppressed nationalities in this effort. This took the form of the November 4th Coalition in several cities–named after the 1972 demonstrations held by the coalition right before the ’72 election. The NLC through the November 4th Coalition gave crucial and timely leadership as a large section of the antiwar forces had fallen under the McGovern hoax of ”vote for me and I will stop the war.”

The NLC put forward the line that given the mounting military defeat at the hands of the Vietnamese people, U.S. imperialism would be forced, before long, to change course in Vietnam, no matter who sat in the White House. It called for demonstrations around the country on election eve, under the slogan “Victory Through Our Struggle, Not Through the Election.” It called for the American people, through persisting in mass action, to continue struggling against U.S. aggression in Indochina. The demonstrations raised, among other demands, support for the Vietnamese peace proposal.

In New York more than 5000 people participated, one third to one half being minorities–Latin, Asian and Black, with 25% of the demonstration working class in composition.

This was followed with organizing an anti-imperialist contingent, drawn from people in many parts of the country, in the January 20 demonstration on inauguration day in Washington, D.C. A demonstration was held at the same time in San Francisco. On May Day ’73 the November 4th Coalition in New York organized a demonstration and rally of 2000 people, 60% of whom were oppressed nationalities and a solid core of which was working class. It should be remembered that these events took place in the general period, though at the end, of the mass upsurge of oppressed nationalities and antiwar struggle.

This was one aspect of the life of the NLC–the carrying out of common work–but the life of the NLC was also characterized by sharp but mainly productive ideological struggle as well as common study. The early meetings of the NLC focused particularly on deepening and further clarifying the understanding of the need for a multinational communist Party. Today this struggle might seem superficial to some, but it must be kept in mind that both the BWC and PRRWO had only recently broken with the line of a party for each nationality and began to grasp there was a single working class in the U.S. (IWK in essence remained wedded to these earlier positions even while stating formal agreement. This line manifested itself particularly in IWK’s reluctance to do work among workers, especially the industrial proletariat, and their constant retreat to work exclusively in Chinatown–and not much of that, to be frank.)

Further, at the time of the YLP-PRRWO Congress there had also been struggle around the role of multinational organization in the pre-Party period. Some members of PRRWO argued for the need for an all white communist organization among white people.

The struggle over this question was closely linked with discussion and debate over the relationship between the national and class struggles and over what were the necessary steps towards a new Party. The RU put forward that the key to creating such a united general staff was active participation in the class struggle and the carrying out of theoretical work and ideological struggle in that context.

This discussion on the Party itself was followed by a period in which the question of line for work in the workers movement was the focus of discussion. This had two aspects: struggle against the IWK line which amounted to opposing the concentration of work in the working class–and actually opposed the line that the working class is the main and leading force in socialist revolution; and the achievement of greater clarity and unity on the part of the other groups around the need to build workers organizations intermediate between the Party and the trade unions, to rely on the rank and file not trade union leaders but not to abandon the unions to these hacks or promote dual-unionism, ripping the advanced away from the rest of the class, etc.

Towards the middle of the period of the NLC’s existence the Black national question was taken up as a major issue of discussion. This discussion occupied a center spot for several meetings, with PRRWO, then BWC reaching unity around the basic position put forward by the RU. Once this struggle began–and it was clear that the RU, PRRWO and BWC were moving toward unity, IWK split.

This was followed by a discussion on the initial Party-building proposal (more on this later). An enlarged meeting discussion of the full proposal was then held, which was in fact the last meeting of the NLC.

But ideological struggle was not simply limited to the confines of the NLC. It was conducted throughout what was then the new communist movement. The forums sponsored by the Guardian newspaper in 1973 were a case in point.

These forums covered major questions, from Party building to the national question. While the Guardian had its intention of using these forums to set itself up as the rallying center of the new communist movement, overall these forums were positive. They focused the attention of many revolutionary-minded people on Marxism-Leninism and how to apply it to some of the burning questions facing the revolutionary movement, and through the role of the RU, BWC and PRRWO a basically correct line was put forward and popularized through these forums in opposition to various opportunist lines.

This, too, was just one example of the fact that the purpose served by the unity of these three organizations was not, as some had slandered, to secretly go off and form the Party, but rather to take concrete steps toward building it through common work and ideological struggle and to be in a stronger position to unite all who could be united around a correct line to form the Party when more of a basis had been laid to take that step.

The three organizations joined in the NLC because they shared basic unity around some major questions–as opposed, for example, to the opportunist lines represented by the October League (OL) and the Communist League (CL). Part of their contribution to laying the basis for the Party was to be to build this unity from a lower to a higher level within the NLC. This was a serious approach to political line and unity, as opposed to trying to opportunistically use the level of unity achieved as a kind of capital, by advertising it publicly. The point was not to proclaim “here’s the center of the movement, here’s the core of the Party” but to actually build political unity through work and struggle.

This approach was again clearly evidenced later by the RU Party proposal, which–taking into account both the unity and differences among the three groups–put forward that the development of things had reached the point where the leap to the Party was required and that differences could only be resolved in the context of moving toward the Party. The proposal called exactly for these three organizations to go out broadly to involve many others in the actual struggle over the Programme for the Party and to unite all who could be united in this process. (More on the RU’s Party proposal later.)

Beyond these Guardian forums there was particularly sharp struggle throughout this period against the right opportunist lines of the October League and the Guardian on the one hand and the dogmatism of groups like the Communist League on the other.

It should also be stated frankly that throughout the existence of the NLC there were certain tendencies by PRRWO towards dogmatism and sectarianism and in the case of BWC a certain tendency during a large portion of the life of the NLC toward reluctance to involve themselves in mass struggle, following a July ’72 organizational conference of the BWC, which planned a three month program of cadre training and clarifying the political line of the BWC as virtually the sole task. This was followed by a series of internal struggles in the BWC, and very little real mass work was done.

A major aspect of the NLC right from its inception was Party building. The NLC came into existence based on the recognition that the formation of the NLC was a step towards bringing the Party into being. It was also understood by all organizations in the NLC that the next big step which the NLC would play a role in facilitating was the formation of the Party itself. The NLC was seen as the cornerstone of the new Party. This was roughly summed up in what became the unofficial slogan of the NLC: “the subordination of each organization in the Liaison Committee to what was coming into being” (the multinational communist Party).

While there was the tendency to downplay the importance of building toward the Party, the truth is quite contrary to the dogmatist invention that the RU in particular and the NLC in general placed Party building on the back burner until one day the RU decided to get the jump on the opportunists and issued a Party building proposal.

The real story and real line differences with the dogmatists, however, are quite another matter. These dogmatists argued that Party building is always the central task when you don’t have a Party, and therefore the principal task must be given to the study of theory and to ideological struggle within the communist movement against opportunism and for a correct line. The RU, since its formation and later in the NLC, stressed the importance of forming the Party as soon as possible. It did not, however, take the position that Party building was the central task for the entire period until the Party was formed. Such a position reduces the question to meaningless generality and phrase-mongering; it avoids the concrete conditions and the necessary steps which had to be taken to lay the basis for the Party.

During the period prior to the formation of the RCP, the period Marxist-Leninists were faced with was characterized by the fact that on the one hand there existed no vanguard Party, but on the other hand there were tremendous mass movements involving large numbers of people, from various classes, strata and groups. It was these struggles that brought forward many forces who, inspired especially by the Cultural Revolution in China, took up the study of Marxism-Leninism, Mao Tsetung Thought. The question posed by these developments was how to bring into being a real vanguard, able to act as a single staff.

The correct road was to begin the process of linking of Marx-ism-Leninism, Mao Tsetung Thought with the mass movement, and in particular to begin the process of merging communism with the practical struggles of the working class. In this way the RU was able to deepen its theoretical understanding, to conduct ideological struggle within the context of carrying out practical work as the main task. To the dogmatists a correct line is simply the working out of an idea in one’s head; they are blind to the basic principle that the correct line must be developed on the basis of and returned to practice–yes, theory must be developed to guide and must be tested in the “funky mass movement” (as leaders of the BWC who later completely degenerated into dogmatism would refer to the mass struggle).

As it was stated in the Communist, Volume 1, No. 2, in the article “WVO: Undaunted Dogma from Puffed-Up Charlatans,” “Studying theory and carrying out ideological struggle, though very important, was not then the key link to resolving these questions–applying Marxism-Leninism to the actual struggles and summing this up was the key link” (p. 78).

The attitude of the NLC towards the question of Party building was summed up perhaps in the most straightforward and frank way by the RU representative at the YLP-PRRWO Congress shortly before the formation of the NLC: “Ideological struggle to resolve differences between these various groups is extremely important; but in order for this to be meaningful, it must go on in the context of actual struggle around common areas of work . . .”

As stated earlier, the NLC was indeed a big step forward; it represented a significant break, at least to a large degree, with some of the major ideological and political weaknesses of the movement of the late ’60s and early ’70s, which were rooted in the nationalism and the tailing after the bourgeois nationalism of the oppressed nationalities, and which held sway among a significant section of the new communist forces.

These lines took many forms in the developing communist movement, such as each nationality working for revolution exclusively from its own “national tent” and exclusively among its own “national sector” of the proletariat.

Perhaps this is brought out most sharply in the early practice of the BWC (1970-72) which refused as a matter of principle to even give leaflets, or sell its paper to white workers at the plant gates. Black or “third world” workers as the vanguard, the denial of the revolutionary potential of white workers, the idea of forming separate communist parties for each nationality, of working separately (perhaps in alliance on programs, tactics and joint struggles)–such was the baggage that, in sometimes “updated form,” was carried over from the movement of the ’60s.

But right from the start the NLC reflected the ideological and political growth of the new communist movement–or at least of a very important section of it. This was reflected most clearly by the BWC representative at the YLP-PRRWO Congress: “Our organization has come to realize that the fundamental problem inside the U.S. is between capital and labor and that the solution to this problem is proletarian revolution. We recognize that the working class in this country is multinational and that to accomplish the task of proletarian revolution requires a proletarian party that represents and leads the whole class.” This was in 1972.

To bring out more vividly how this position represented significant forward motion, a good example in contrast is the line put forward by the League in 1970 and later taken as part of the guiding line of BWC and many others throughout the developing revolutionary and communist movement up to that time. In an interview in the Leviathan, Volume 2, June 1970, a representative of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers stated boldly: “Whites in America don’t act like workers. They don’t act like a proletariat. They act like racists. And that is why I think that blacks have to continue to have black organization independent of whites. In terms of the future it depends on whether or not whites can make the transition of giving up, you know, the privileges that they have.” This political conclusion was reflected in the early platform of the BWC: “. . .we hold firm to the position that the working class of blacks, Chicanos, Puerto Ricans, Native Americans, Asians, and other Third World people are the vanguard force in the United States ...” (from the “Constitution for the Black Workers Congress,” 1971, p. 1).

The critical point here is not merely to recount what group held what line back when. While this is important, the central point is that the line of “Bundism,” of adapting socialism to nationalism, ran throughout the history of the revolutionary movement in the U.S. in the ’60s and early ’70s and the development of what was then the new communist movement (and it is alive and well in many so-called communist organizations or “parties” today).

One of the earlier forms this line took was that Black people and other oppressed nationalities in the U.S. (perhaps in alliance with the peoples of the Third World) could and would make revolution alone in this country, or with a small number of white supporters mainly from the petty bourgeoisie. The situation of the oppressed nationalities in the U.S. was seen as being essentially the same as the peoples of the colonial and semi-colonial world of Asia, Africa and Latin America, and the task of the revolution seen as similar–national liberation.

James Forman, onetime Executive Secretary of SNCC and later the central figure in the BWC from 1970-72, set forth this position most clearly in his speech, “Liberation Will Come from a Black Thing” (1967):

To view our history as one of resistance is to recognize more clearly the colonial relationship that we have with the United States.” In the same speech he goes on to say, “The serious conditions in which we find ourselves as a people demand that we begin talking more of the colonized and the colonies.

In another speech, entitled “Total Control as the Only Solution to the Economic Problems of Black People” (1969), Forman further elaborates on the implication of this line:

We say that there must be a revolutionary black vanguard and that white people in this country must be willing to accept black leadership, for that is the only protection that Black people have to protect ourselves from racism rising again in this country.

Racism in the U.S. is so pervasive in the mentality of whites that only an armed, well-disciplined, black-controlled government can insure the stamping out of racism in this country. . . We say . . . think in terms of total control of the U.S. Prepare ourselves to seize state powers. Do not hedge, for time is short and all around the world, the forces of liberation are directing their attack against the U.S. It is a powerful country, but that power is not greater than that of Black people. We work the chief industries in this country and we could cripple the economy while the brothers fought guerrilla warfare in the streets.

This line, however, in the period in which it developed and held sway, represented a big step over the militant reformism of the early and mid-’60s. It represented a break with the line of passive resistance. It looked for the solution of the liberation of Black people and other oppressed nationalities outside the bounds of the system. It placed the struggle of the oppressed nationalities in the context of worldwide struggle against imperialism, particularly the fight being waged by the peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America.

On the other hand this line was a far cry from a scientific analysis of the actual condition and requirements even of Black liberation–it was not a line which showed the actual relationship between Black liberation and revolution in the U.S., which could only mean proletarian revolution. While it was a real advance in that period, in the end this notion of liberation or revolution proved to be illusory.

As Mao points out in On Practice, “If a man wants to succeed in his work, that is, to achieve the anticipated results, he must bring his ideas into correspondence with the laws of the objective external world; if they do not correspond, he will fail in his practice. After he fails, he draws his lessons, corrects his ideas to make them correspond to the laws of the external world ...” (Selected Readings, p. 67).

In the face of the fact that such a line could not lead to further advances, some forces began to seriously take up the study of Marxism-Leninism and see that revolution in a capitalist country like the U.S. means proletarian revolution. This new understanding, however, was often still combined with the baggage of the earlier period, producing an erroneous political current, the line that the proletariat will make revolution, but Black and other oppressed nationality workers are the only real proletariat.

This went hand and glove with the infamous “white skin privileges” line. According to this reactionary position the white worker has been bribed off, has sold out through a “gentleman’s agreement” between the ruling class and the masses of white workers through the “labor lieutenants” of the capitalist class. The white workers have supposedly agreed not to make trouble as long as they have privileges denied Blacks; hence the cornerstone of the white workers becoming revolutionary is for them to repudiate their privileges. The implication of this runs counter in every possible way to the approach of the proletariat to inequality–”an injury to one is an injury to all,” not “injuries must be suffered equally by all.”

When all is said and done this position lets the bourgeoisie dead off the hook, and ends up holding hands with the Kerner Report, reducing the fight against national oppression to the subjective attitude of white people and particularly white workers.

Yes, white workers do have some petty privileges denied Black people and other oppressed minorities but these petty privileges as compared to a lifetime of exploitation and oppression are exactly that–mere crumbs. Nor is the source of the oppression of Black people these crumbs, or anyone’s attitude. Black people suffer dual oppression in the real world by a real monster–U.S. monopoly capitalism which fosters and promotes racism and chauvinism.

As this white skin privilege line, too, ran up against a wall, showing itself to be a mortal sin against objective reality, some of these forces studied Marxism-Leninism more deeply, summed up this development and grasped more firmly, that “the question is not what this or that proletarian, or even the whole proletariat at the moment considers as its aim. The question is what the proletariat is, and what, consequent on that being, it will be compelled to do” (from The Holy Family, Marx). In a word, many began to understand more fully that the proletariat is an objective social class, defined fundamentally by its relationship to the means of production and that in the U.S. the proletariat is multinational.

In order to understand why these earlier incorrect lines were able to flourish on the one hand and on the other hand the significance of the development of the NLC and later the struggle waged by the RU against these incorrect lines and particularly the retreat of BWC and PRRWO back to nationalism, it is necessary to review the development of the revolutionary mass movement and what was then the new communist movement.

In the late ’50s the Black people’s struggle for civil rights erupted and later developed into the modern Black liberation movement shaking the country at its very foundations. This movement produced many revolutionary-minded people and gave tremendous inspiration and encouragement to millions of other people in the country–and around the world–who were fighting back against the same imperialist ruling class, especially other oppressed nationalities, the youth, students, women and sections of the working class in the U.S.

This occurred at a time when U.S. imperialism still sat alone atop the imperialist pile, when there was a lull in the workers movement and, due to the revisionist betrayal of the CPUS A, the working class was without its general staff, its vanguard Party. The workers struggle, while often breaking out, was mainly on the trade union level, and not marked by a high degree of class consciousness or political struggle against the ruling class and its various forms of oppression of the people.

It was in this context, with the upsurge of Black people, other oppressed nationalities and students and youth generally, that many people began to see there was something more at stake than a particular injustice or a struggle they were involved in, that there was something more fundamentally wrong with society, and that the problem couldn’t be solved without getting to the root of it.

Many activists began to look at the experience of other countries where revolutionary struggle was being waged. Some began to see there was only one ideology which enabled people to consistently and thoroughly stand up to imperialism, one ideology which, when grasped by the masses enabled them to change the material conditions they faced in a thoroughgoing way–Marxism-Leninism. In a word, many began to see the need for revolutionary theory–though, of course, this did not mean that even the most advanced forces in the U.S. at the time grasped this theory and applied it in a consistent, scientific way.

The rapid development of the Black struggle was accompanied by the development and growth of Black revolutionary organization that did much to change the political map of the U.S. Revolutionary ideas and the conscious study of Marxism-Leninism spread among a large section of Black people; this was also a major force in turning large sections of other oppressed nationalities and white youth to the study and practice of Marxism-Leninism.

The group that by far had the most profound effect in turning many heads towards revolutionary struggle and Marxism-Leninism was the Black Panther Party. The BPP’s ideology was, to be sure, eclectic–reflected most sharply in their characterization of the “brother on the block” (i.e. unemployed youth in particular) as the leading social force in making revolution and picking up the gun (“offing the pigs”) as the principal content of revolutionary work in the U.S.

It was, however, the BPP that placed the issue of revolution on the table in a way that it had never been done before since the betrayal by the CPUSA. It was the BPP that most clearly stated that the contradiction between the masses of American people and the system of imperialism could only be resolved through revolutionary struggle. The BPP however, exactly because it did not understand the role of the working class and the way in which Black workers, in particular, could act as a kind of link between the Black liberation struggle and the overall workers movement, could not grasp the correct relationship between Black liberation and the revolutionary struggle as a whole in the U.S.

Still it was the BPP at that time that most forcefully (if not thoroughly) raised the banner of Marxism-Leninism, and delivered telling criticism against those in the Black liberation movement such as the cultural nationalists, Pan Africanists and Black petty bourgeois reformists who all sang in single chorus, Marxism-Leninism is a ”honky thing” and has no relevance to Black people.

The raising of the banner of Marxism-Leninism by the Black Panther Party also administered a positive shock to those white youth and students who sought to create a new revolutionary ideology–New Leftism–claiming Marxism-Leninism was nothing but the obsolete dogma of the “old left.”

As was said earlier, while the BPP placed these things squarely on the table, the BPP itself remained in the final analysis within the walls of petty-bourgeois revolutionism and petty-bourgeois nationalism–its nationalism being characterized by such things as its advocacy of the line of a Black vanguard. Ultimately this inability of the BPP to make a leap beyond this outlook meant that the BPP was turned into its opposite, ceased to play a revolutionary role and degenerated.

Another important development which began to take place beginning around 1968 was the insurgent movement of Black workers which swept the country particularly in the basic industries. Black rank and file groups sprang up to combat the oppressive conditions of factory life and the racist sellout policies of the union misleadership. This movement reached its highest political expression with the development of the Revolutionary Union Movement based principally in the auto plants of Detroit and referred to earlier.

In 1969 the development of the RUM resulted in the formation of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, also Detroit based. The General Policy Statement and Labor Program of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers laid out quite explicitly where the League was coming from–“The League of Revolutionary Black Workers is dedicated to waging a relentless struggle against racism, capitalism and imperialism. We are struggling for the liberation of black people in the confines of the United States as well as playing a major revolutionary role in the liberation of all oppressed people in the world” (p. 1). This showed both the strengths and weaknesses of the League.

The League represented a significant advance for the Black liberation movement and the overall workers movement. In addition to sparking struggle in the working class–even, despite narrow nationalist lines, among white workers–the development of the Revolutionary Union Movement and the League acted as sort of a revolutionary kick in the pants to turn toward the working class some forces in the revolutionary movement who had felt the industrial proletariat, Black workers as well (if not as much) as whites, had been bought off; that it either actually benefits from imperialism, or is so bribed by the imperialists that at best it will fall in line at the rear of the revolutionary ranks somewhere far down the road to revolution.

However, while the League began to turn some activists in the revolutionary movement towards the working class, both in the case of the League itself as well as many revolutionaries who began to turn towards the working class, they summed up only half of reality–that Black and other oppressed nationalities workers were not bought off.

The communist forces which arose in this overall period were marked by both its positive factors–the great inspiration of the revolutionary national movements–and on the other hand its negative aspect–the revolutionary movement that had very little roots in the workers movement generally and among white workers in particular. Further, since these young communist forces had been cut off from the historical experience of class struggle as summed up by the leaders of the international communist movement, there was a strong basis for bourgeois ideology within the new communist movement, with regard to the national question mainly taking the form in those times of narrow nationalism and tailing after bourgeois nationalism of the oppressed nationalities.

Another thing influencing this development was the fact that in the face of the storm of Black rebellion the ruling class panicked, responding with the stick and the carrot as well. Under the guise of economic development and Black capitalism, the government pumped millions of dollars into Black enterprises.

Black capital went from $500 million in 1965 to $1.6 billion in 1973. Poverty programs were set up in virtually every ghetto in the country, while some professional jobs opened to Blacks, Puerto Ricans, Chicanos, etc. In addition, in several major cities which had become in the main Black, a number of Black faces replaced white faces as mayors, police chiefs and a whole host of bureaucrats. The essence of all this was to build up the petty bourgeois and bourgeois forces among the oppressed nationalities in an effort to put a brake on the struggle and divert it away from its revolutionary thrust–co-opt it.

This was coupled with somewhat of a tactical shift by the ruling class in the sphere of ideology and public opinion. While maintaining and even stepping up its chauvinist poison propaganda about the inferiority of the oppressed nationalities and pointing to them as the cause of their own oppression–and problems in society in general–the ruling class especially through its so-called liberal wing put tremendous effort into promoting and spreading bourgeois nationalism among the oppressed nationalities.

This took the form of pointing to white people and especially white workers as the real enemy of Black people and the source of their oppression. This bourgeois line was not walled off from the revolutionary movement, including the new communist forces, but in fact in some quarters it was picked up and promoted in more subtle forms and sometimes not so subtle forms.

Particularly with this backdrop, the NLC was an extremely positive development and was, as noted earlier, a testament to the ideological and political growth and developing influence of communists of all nationalities in the mass movement.

In the case of BWC and PRRWO what characterized these groups then and for much of the period of the NLC was their general forward direction toward Marxism-Leninism, towards taking the stand of the working class and away from nationalism and Bundism (adapting socialism to nationalism). This positive aspect of their development was not without its negative side, however, a tendency towards nationalism and Bundism in new forms.

For example, the YLP resolution at the Congress of 1972 (in which YLP became PRRWO), while stressing the necessity of building a single multinational party, also stated that in the United States, before that Party could be built, Marxist-Leninist organizations had to develop among Afro-Americans, Chicanos, Asians, Native Americans (meaning separate organizations for each nationality) to analyze their work and experiences with the proletariat of their nationality to create a base for a multinational proletarian Party in the future.

It was exactly this Bundist thinking that led PRRWO to push virtually as a “matter of principle” for the inclusion of IWK in the NLC, as there was clearly no ideological or political basis for IWK’s inclusion–no Marxist-Leninist basis, that is–outside of the faint possibility they might in the course of the NLC reverse their course. All the other groups held at least basic unity around the fact that the multinational proletariat was the main and leading force and needed a single vanguard representing it as one class. For IWK it was quite another matter, however. At the YLP-PRRWO Congress, IWK called not for unity of the multinational proletariat but for a common front of the oppressed nationalities. “The present stage in the American revolution calls for unity among Black, Brown and Asian people in the U.S.” Further IWK upheld the reactionary line of “white skin privileges” and spoke almost entirely of basing themselves not among the industrial proletariat but on “community work.”

BWC, which knew nothing of IWK at the time, went along with PRRWO’s proposal to include IWK for the same Bundist reason that had prompted PRRWO to make the proposal in the first place.

The RU struggled against IWK’s inclusion, based on IWK’s line and practice, but felt in the end that the general forward motion of such a committee was more important than making the issue of IWK a splitting matter.

This tendency towards nationalism was also present in the BWC which, for example, defined the scope of its task as being “to sink deep roots among the Black sector of the proletariat” (July 8 Conference Report, 1972). However, the principal aspect of both PRRWO and BWC and their motion at that time was away from this baggage.

During this period, the matter of building the unity of the proletariat became much more than a declaration of intent. The three organizations attempted to build multinational organizations in the workplace, took up the task of working to build the struggles of the unemployed of all nationalities through the Unemployed Workers Organizing Committee, and built multinational coalitions such as the November 4th Coalition. BWC, while still attempting to build all-Black forms of mass organizations, also undertook the building of a multinational coalition around police brutality against Black people in Atlanta.

However towards the end of the existence of the NLC, and shortly before the discussion of the Party building proposal, the retreat back to nationalism began to manifest itself sharply. As opposed to moving forward in the direction of the need for the organizational unity of all proletarians and particularly the formation of the single vanguard of the working class, BWC and PRRWO began a steady backtrack, that was later to take leaps and bounds backwards.

This drift first began to manifest itself in PRRWO and BWC’s attempt to create more sophisticated justification for separate communist organizations based on nationality, for splitting the workers’ cause, organization and movement along national lines.

Towards the end of the NLC period, PRRWO set for itself, as its central task, the building of national forms of mass organizations around the democratic rights of the Puerto Rican national minority based on three principles: 1) the right to speak their language, 2) to struggle for bilingual programs that really teach Puerto Rican people’s history and culture, 3) the right to mobilize freely and agitate for the national liberation struggle of Puerto Rico.

These things should have been taken up by PRRWO but PRRWO should not have restricted its activity nor certainly its outlook to taking up these questions, nor should these questions have been seen as the sole responsibility and province of Puerto Rican communists.

BWC for its part put forth its central task as “the raising of the proletarian banner in the Black liberation struggle and to build the leadership of Black workers in the struggle of the entire multinational working class and the anti-imperialist struggle of all the people in the U.S.”

BWC began to rigidly stress that in order to build a lasting multinational proletarian Party, a Black communist organization must raise the proletarian banner in the Black nation and defeat bourgeois nationalism. The essence of this line was a retreat back to “sole representation” with the bottom line that the Black masses generally and the Black workers in particular could not be won right then to the line of a communist Party with a correct line and correct methods of work because it had white people in it. Hence a Black communist organization must first wipe out bourgeois nationalism–quite a feat!–in order to prepare the way. The “leading role of Black workers” line was also showing its head.

In general, however, these lines were just emerging in what became an overall backward turn and they still represented mainly seeds of differences which could possibly be resolved through struggle in the course of moving to the Party.

As pointed out earlier, some have claimed the Party proposal put forth by the RU in late 1973 was simply an opportunist maneuver of the RU to turn itself and its clique (meaning BWC and PRRWO) into the Party; it was an attempt to build a Party behind closed doors, they say.

The essence of the proposal was far different. At the heart of the proposal was the matter of ideological and political line, the Party programme. A draft or several drafts would be circulated publicly among all organizations, collectives and individuals with the objective of “uniting all who can be united” to form the Party. The adoption of the final programme and the selection of leadership of the Party were to be accomplished from the bottom up as opposed to top down, taking place at the founding congress. The members of all the organizations and other forces would be represented on a proportional basis (one delegate for so many members), guided by the principle all communists are equal regardless of nationality or the size of the group they had belonged to. The delegates would vote as individuals, not in blocs.

Further, in order to unite all who could be united, there would be teams set up–“flying squads”–with the task of contacting and struggling with independent collectives, organizations and individuals that were not marred by a consolidated opportunist line such as OL and CL–unless, of course, they repudiated this line. The flying squads were to go throughout the country.

It was proposed by the RU that the National Liaison Committee be expanded to include representatives from other forces that would be unifying around the building of the new Party. It was felt that if the three organizations took up this task, working together they could unite many forces.

BWC and PRRWO opposed this with Bundism, claiming that these collectives and individual Marxist-Leninists would be mainly “white petty bourgeois.” This completely overlooked the fact that there did exist at that time various Black and other oppressed nationality collectives as well as a number of people from the oppressed nationalities who were beginning to break with nationalism and turn towards Marxism. The RU further pointed out to BWC and PRRWO that while class origins are important the critical and decisive question is ideological and political line.

Although BWC and PRRWO rejected the Party proposal and broke up the Liaison Committee, the RU and others did carry out the line of “uniting all who can be united” to form the Party, contacting many forces throughout the country, discussing the need to form the Party in the immediate period ahead, the importance of building such a Party, and on what ideological and political basis it could be built, etc. The RU conducted extensive polemics against all major opportunist trends, and held Party building forums, drawing in some places many hundreds of people.

Even after BWC and PRRWO broke off the Liaison Committee, and initiated public polemics, the RU’s approach was that, while things were clearly on a downhill road for the BWC and PRRWO, the RU still called on these forces to unite on the basis of Marxism-Leninism to build the Party.

The RU stated at that time (as expressed in “Marxism vs. Bundism,” page 61, Red Papers 6):

We would like to remind the BWC and PRRWO of the high spirit of unity that marked the original formation of the liaison. This was based not on an absolute agreement on every political question, but on the commitment to subordinate the interest of our particular organizations to the overall and general interest of the proletariat and to ’what was coming into being’–the Party. This was not an organizational question of abolishing the democratic centralism of the separate organizations, but an ideological question of putting our priority on working together to build the mass movement and build toward the Party.

For our part, the RU has always recognized that organizational unity and merger would have to be based on developing closer and closer political unity. But we have always felt sure that this would be achieved so long as we all upheld the spirit of serving the people with which the liaison was formed. It was in this same spirit that we made our party proposal to the liaison committee. And we are convinced that by reviving and upholding this original spirit, principled unity can be achieved through struggle and we can move forward together to ’what is coming into being’–the Party and the revolution.

But because of their opportunist lines the BWC and PRRWO were bent on creating a breakup of the Liaison Committee. They were not interested in reviving the original spirit of the Liaison Committee; instead they were intent on reviving nationalism in the guise of Marxism.

It is by no means surprising that all-out struggle would break out with the issuing of the Party building proposal by the RU in late 1973, for the formation of the Party required a leap.

The Party proposal in many ways represented the tip of the iceberg, so to speak. Why? Because in order to build a single unifying center–a Party–to develop a battle plan, a Party programme to guide the Party, in order to lead the class, to merge the national and class struggle, required a break with the petty bourgeois baggage of the past movement.

The whole of the communist movement was confronted with the necessity to make this leap–and in the case of BWC and PRRWO as for many others, it meant breaking with the most sacred of sacred possessions, the supreme sacred cow, narrow nationalism and the raising of the national question above every other–above and apart from the scientific class stand of the proletariat and the class struggle.

Further it was not as if the struggle just simply jumped out of the sky. As the objective conditions were changing, including the fact that the struggle of the whole class was beginning to grow, the mass movement had come up against the absence of a genuine vanguard to lead the struggle and build the united front under proletarian leadership to overthrow capital. The consciousness of the need to unite, along with the growing awareness that the whole system is rotten, was developing among all sections of the working class and masses.

What was required was to move the mass struggle to a higher level, showing the masses how to build unity, how to identify the enemy and how to fight him. This demanded an end to the scattered circles, activity working at cross purposes, and duplicating efforts. This situation called for uniting all who could be united around a correct line and programme to form a single general staff.

Thus, while BWC and PRRWO played a very progressive role at one stage in the development of the new communist forces, as the objective conditions made it impossible to continue on the old basis, BWC and PRRWO, like many others, were confronted with either moving forward on a qualitatively new basis or falling backward.

Unfortunately, BWC and PRRWO took the latter course, retreating into nationalism and then dogmatism combined with nationalism as their guiding ideology. For these reasons BWC and PRRWO were no longer able to contribute to building the Party and the revolutionary movement in general, but set themselves on an opposite course, resulting in further splits and degeneration on the part of these organizations.

In many ways it was as Stalin had pointed out regarding the development of the working class movement in Russia and the Bund: “Even before 1897 the Social-Democratic [Marxist] groups active among the Jewish workers set themselves the aim of creating a ’special Jewish workers’ organization. They founded such an organization in 1897 by uniting to form the Bund. That was at a time when Russian Social-Democracy as an integral body virtually did not exist. The Bund steadily grew and spread, and stood out more and more vividly against the background of the bleak days of Russian Social-Democracy. . . . Then came the 1900s. A mass labor movement came into being. Polish Social-Democracy grew and drew the Jewish workers into the mass struggle. Russian Social-Democracy grew and attracted the ’Bund’ workers” (Stalin, “Marxism and the National Question,” Vol. 2, p. 346, emphasis in original).

While the situation in the U.S. in 1973-74 was not exactly the same, nor is it correct to analyze history by parallel, the critical point is however the same, and the general lesson does hold true. To continue on the old basis when the objective and subjective condition demand a leap forward is to go backward.

One specific thing that kept BWC and PRRWO from making a leap forward was a tendency that had existed in both organizations, although it had not all along been the principal aspect. This was not summing up on the basis of Marxism-Leninism, looking for the essence of problems on the basis of ideological and political line, but instead adopting get-rich-quick schemes, hoping to develop enthusiasm into a substitute for a correct line and hard and patient work.

A good example of this came up towards the last meeting of the NLC. BWC and PRRWO had incorrectly summed up that the more they had taken up Marxism-Leninism the more isolated from the masses of the oppressed nationalities they had become–though this was not put forward in quite so straight up and blatant a way. Of course, taking up Marxism-Leninism does not enable one to have quick success or that automatically at any given time you have broad support among the masses. But it provides a basis of applying mass line to unite with the needs of the people in the practical struggle, while being able to point beyond that to the general and long-term interests of the working class and masses of people, and to persevere through the twists and turns of struggle, to keep sight of the long-range goal, and guide the mass movement toward that goal.

But looking for get-rich-quick schemes BWC and PRRWO failed to grasp this. This began to take sharp focus in the BWC with the consolidation of the line put forward by the RU on the Black national question–that Black people in the U.S. are a nation with their historical homeland in the Black Belt but today are dispersed from that homeland and concentrated mainly as workers in the urban areas of the North and South–that the Black national question in the U.S. is no longer in essence a peasant question but a proletarian question and that the Black nation in the U.S. existed under new and different conditions (more on this question later).

BWC felt now it was set to go to recreate the BPP or the League of Revolutionary Black Workers–on a higher basis, of course. However, it is not so simple a matter to recreate the past because both objectively and subjectively the conditions do not exist. Again this line itself was rooted in the case of both BWC and PRRWO in nationalism, namely that once communists of the oppressed nationalities take hold of Marxism-Leninism they could really get this thing going. When this petty bourgeois scheme fell short, when there was no instant mass base that fell into line behind BWC and PRRWO, it was concluded that groups like the BPP, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers and Young Lords Party were able to get a base among the masses of oppressed nationalities because they were both revolutionary nationalist and Marxist-Leninist.

This was the wrong conclusion, rather than summing up correctly that these groups, while progressive and even revolutionary and while raising the banner of Marxism-Leninism for a time, did not make a complete rupture with nationalism and were essentially revolutionary nationalist and not Marxist-Leninist.

The point is not that such groups automatically failed because they were not from the start thoroughgoing Marxist-Leninists. Such an analysis is metaphysics, not dialectics. The point is that for such groups–and this was directly relevant for BWC and PRRWO in early 1974–continuing to advance would have required making a qualitative leap, to grasp and apply Marxism-Leninism more thoroughly, and definitely not to go backward into bourgeois nationalism.

However, failing to draw the appropriate lessons from this, BWC and PRRWO began to take their weakness in ideology and raise it to a matter of principle. So the next get-rich-quick scheme consisted in first combining two into one–Marxism and nationalism.

This was followed by another erroneous position. To recreate the movement of the late ’60s, it was felt it was necessary to have an upsurge. So BWC and PRRWO set about to invent such an upsurge, or create it out of subjective desire to see it. BWC and PRRWO refused to face objective reality, denying that the movement of the oppressed nationalities had grown through a flow reaching a high tide in the mid and late ’60s–and then began to ebb in the early ’70s.

In their view there was no flow and ebb but just one continuous upward movement in a straight line, and to say that the struggle had ebbed was “racist,” was to say the oppressed nationalities were “bogged down.”

Further this overall line reflected BWC and PRRWO’s retreat from a correct summing up of the movement of the oppressed nationalities in the ’60s, which was sharply underlined in the September 1977 Revolution.

Similarly, the powerful Black liberation struggle which reached its high tide in the ’60s also suffered from the lack of class conscious working class leadership within it. . . . As in the antiwar movement, the lack of a strong working class ’pole’ within the Black liberation struggle made it easier for wrong and harmful tendencies to arise and more difficult to combat them. . . . And without the working class being in a position to clearly point a direction forward for the struggle, many were easily taken in by various schemes promoted by the capitalist enemy to direct the struggle from the real target–themselves.

This brings us right down to the heart of the matter which divided RU on the one hand and BWC and PRRWO on the other, Marxism vs. Bundism. At the outset of the struggle there were two questions around which the three organizations were divided into two camps: First, is the slogan “Black Workers Take the Lead” a correct slogan for the working class movement or for the Black liberation struggle in particular? And second, the issue of revolutionary nationalism–is revolutionary nationalism the same thing as Marxism-Leninism, is there an equal sign between them? That today a Black Marxist-Leninist must be a revolutionary nationalist meant that ideologically they are the same thing.

The issues raised in this struggle were very important in the development of the correct line and program on how to wage the fight against national oppression as part of the overall class struggle and how to bring about the merger of the national and class struggle.

To understand the actual development of this struggle it is important to grasp that while the RU essentially held a proletarian line, for the RU, too, it was a matter of motion and development and one dividing into two in this matter as well. The RU had also held many of these incorrect lines, or aspects of them.

This is most evident, for instance, in a pamphlet on a strike by workers at Temple University in Philadelphia, published by the Revolutionary Union in 1972. This pamphlet called Black workers “the most advanced section” of the working class–in essence the “Black Workers Take the Lead” line. In fact the pamphlet was entitled “Black Workers Lead Strike to Victory.”

It was in fact through the course of trying to apply such positions that the RU began to sum up that these policies were in contradiction to a correct line and to the general development of the RU’s work, that they were not aiding the revolutionary struggle, not aiding the building of the unity of the working class, not aiding the development of the struggle of the working class as a whole or the Black people and other oppressed nationalities but in fact were holding it back.

In one plant, for example, the RU was putting forward the need for a Black shop steward. In opposition to this, many workers raised questions and objections. One Black worker pointed out, “What’s important is that we have somebody good to represent us, to fight against discrimination in the plant and to fight around all the questions the workers here face. It’s not the question of what nationality somebody is that’s important, but what stand they take and what they fight for that’s important.”

One white comrade under the influence of this incorrect line failed to do anything about a blatant act of discrimination against a Black worker in the shop, because he was white and “couldn’t give leadership to the national struggle.” In another case a Black comrade influenced by this line went into coalitions and committees of Black people, including many petty bourgeois Blacks, trying to push “Black Workers Take the Lead” down their throats and was unable to unite people broadly. In yet another case where there had been some police shootings of several members of the Nation of Islam (now the World Community of Islam in the West), the Bundist line advocated doing nothing–white comrades shouldn’t take this up, and Black comrades cannot do anything because they are connected with whites (see Red Papers 6, “National Bulletin 13,” by the RU).

It became clear that these erroneous positions prevented communists from getting involved in applying a correct line in important struggles. Under the cover of upholding the national struggle this line led communists to stand aloof from struggle on this front, and in the working class as a whole it meant maintaining divisions.

On the basis of this experience and the need to sum it up, a sharp struggle broke out with the RU, with a small handful, led by the RU representative to the NLC, taking a reactionary stand of upholding all that was wrong and reactionary in these positions. This representative carried this struggle into the NLC and more generally colluded with leaders of the BWC and PRRWO to oppose and attack the RU in its move to sum up and correct its errors and the line that led to them.

The RU as a whole overwhelmingly rejected this line, while BWC, PRRWO and a few within the RU (who soon split from it) went on to seek profound justifications for it. This led to the struggle between the organizations, which immediately was felt most sharply on the NLC level.

In fact it was the NLC that became one of the chief headquarters of bourgeois nationalism. In the later stages of the NLC it more resembled a “third world caucus” than communists coming together to hammer out serious matters of line and to sum up and give guidance to practical work.

In a real sense, however, it was the RU representative who took the lead in consolidating many of these incorrect lines–though to be sure there already existed fertile soil for this development in BWC and PRRWO.

This relates to the fact that in the way the RU approached the NLC involved a concession to nationalist tendencies in BWC and PRRWO. This was manifested in the RU’s decision to have as its representative to the NLC a Black member of its leadership in place of the leading RU comrade who had represented it at the YLP/PRRWO Conference in 1972 when the NLC was first formed. The erroneous thinking behind this decision was the idea that having a Black to deal with would “soften” things for BWC and PRRWO in relating to a multinational organization. The full consequences of this error were felt later when the RU representative on the NLC used it as a base for pushing a reactionary nationalist line.

In the later days of the NLC the question of Black leadership of the American revolution was stressed, as a matter of principle, and became a major rallying cry. The line was put forward that since there is a Black nation therefore before a Party can be formed there must be a Black communist organization to have a significant base in the Black proletariat and deal a major defeat to the Black bourgeoisie’s hold on the Black masses.

Then there was the position that revolutionary nationalism is Marxist-Leninism for a communist of an oppressed nationality.

The BWC had never previously held such a position, and PRRWO while holding this line back in the days of the YLP had never put it forward in recent years and had in fact moved away from it. In fact it was promoted by the RU representative on the NLC, representing to a large degree, especially on this question, his own views and not the RU’s. This was followed by the “caucus” (NLC) demanding an all-Black meeting to sum up the Black liberation movement as opposed to a meeting of those with the most extensive experience and most of all those with the best grasp of Marxism-Leninism, including its application to this question, to sum up the Black liberation movement. In fact the spectre of Black nationalism was rising to such a degree that PRRWO, which also had Black members, had to ask in a subtle way, couldn’t Puerto Ricans attend such a meeting?

To keep this line from going so far as to cause a split between Blacks and Puerto Ricans, the banner of Black and Puerto Rican unity became a big rallying cry–with the bottom line that Puerto Ricans are really just like Blacks. They can “party,” “get down,” etc.–in a word, they are basic brothers and sisters. But in the end this Black and Puerto Rican unity would also deteriorate, showing itself as only a mere opportunist marriage of convenience.

Following BWC and PRRWO’s break with the RU and later with the CL, their unity soon broke up. The only basis for real and lasting unity among people of different nationalities is a correct ideological and political line representing the outlook and interests of the working class.

Towards the last days of the NLC some of the nationalism was nothing but a straight up, unrefined, mask torn off and coming out naked “my nationality first and only.” Chicanos were attacked outright by the RU representative who created a distinction between Chicanos and Mexican-Americans, claiming the former are part of the oppressor (white) nation, that they are descendants of the original holders of Spanish land grants in the Southwest, that given they are white (according to some bourgeois legal classifications) unlike the “dark-skinned Mexican-Americans,” they do not really suffer national oppression. Hawaiians were referred to by the RU representative as “pineapples,” Chinese Americans as nothing but petty bourgeois, and Japanese as white people.

While hardly anyone from BWC and PRRWO united with this blatant national chauvinism, the basic line of nationalism was united with by all. During this period and increasingly as BWC and PRRWO sank deeper into nationalism and dogmatism and the polemics between them and the RU sharpened, BWC and PRRWO members could be seen wearing red, black and green (the so-called “national colors” of Blacks) caps, scarves, buttons, etc. and some were even referring to the white masses as “honkies” and white communists as “white boys,” longing for the day when we get “our state” and be rid of these racists (more on this later).

The line of “Black Workers Take the Lead” was in essence a throwback, in more sophisticated form of course, to the position that said Black and other oppressed nationalities are the only real workers. The line of “Black Workers Take the Lead” as put forth by BWC had both a political as well as organizational content. Firstly, BWC and PRRWO seized on a correct aspect–that the Afro-American people’s struggle had been a “clarion call to all the exploited and oppressed people of the United States to fight against the barbarous rule of the monopoly capitalist class” (as powerfully stated by Mao Tsetung in 1968, emphasis added). Further the struggle of Black workers in particular had been a spark in the struggle of the industrial proletariat as a whole. But they seized on this correct aspect only to twist it into its opposite –combining two into one by confusing a struggle that had played an advanced role with the question of the conscious leadership of the working class and the masses generally.