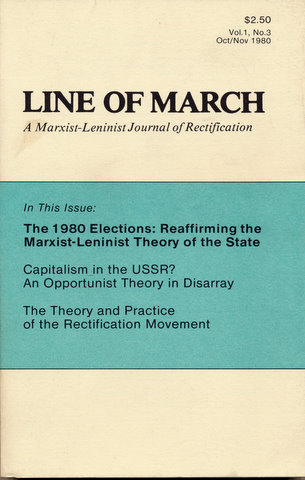

First Published: Line of March Vol. 1, No. 3, October-November 1980.

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

The great spectacular of bourgeois politics–the quadrennial ritual of the ballot box by which U.S. imperialism’s chief executive is designated–is at this moment approaching its grand finale.

For almost a year the attention of the masses has been directed toward the reassuringly familiar stage business of a presidential election, the very terminology of which (trial balloons, dark horses, hats in the ring, balanced tickets, running-mates, etc.) is strongly suggestive of its obligations to the work of circuses. Faithful to the scripts of yesteryear, the 1980 election is playing out its appointed hour upon the stage with a reenactment of those time-honored rites which serve to impart an image of stability and historical continuity to the rule of U.S. capital.

It is not mere poetic license which has led the bourgeoisie’s own commentators to describe this process as a pageant. That is the essence of this ballet which begins with the endless rounds of declared and undeclared candidacies, continues with the sweep of the nominating primaries played out against shifting backdrops which range from the snows of New Hampshire to the ghettoes of Chicago, reaches a crescendo with the three-ring circuses called political conventions, and concludes with the high drama of public counting of ballots on the nation’s television screens.

What is the purpose of this elaborate extravaganza? Marxists have long noted that insofar as its stated purpose is concerned–determining the question of political power in modern society–it is no more than a charade, a political sleight of hand in which the more things seem to change, the more do they remain the same. But Marxists do not deserve any special credit for making such an observation. One hardly has to be a Marxist to grasp the fact that bourgeois elections do not, in any way, impinge upon or alter questions of power. The general cynicism among the masses toward politics and politicians–a cynicism which runs far deeper than can be measured solely by noting the large numbers of people who do not bother to vote in elections–is itself proof that the futility and corruption of bourgeois politics has become a part of U.S. folklore.

But because bourgeois elections are a charade and do not alter the fundamental relations of power and property does not at all signify that they are without meaning or political significance. And those among the communists who content themselves with merely denouncing the bourgeoisie’s electoral process without undertaking to explain the actual political content of each election can hardly be said to be offering vanguard leadership to the working class.

To analyze that content we might well begin by noting Engels’ comment that bourgeois elections under the conditions of universal suffrage offer a “gauge of the maturity of the working class.” But they offer more than that. These elections also provide an extremely important window into the ways in which the bourgeoisie views its own contradictions. In fact, bourgeois elections are a gauge of the political motion of all classes; and communists, if they are to fulfill their vanguard role in relation to the working class, must be prepared to offer the most advanced explanation of this political motion which all can see but which few fully comprehend. For as Lenin pointed out (What Is To Be Done?): “Those who concentrate the attention, observation and even consciousness of the working class exclusively, or even mainly, upon itself alone are not Social Democrats; for its self-realization is indissolubly bound up not only with a fully clear theoretical–it would be even more true to say not so much with a theoretical– as with a practical understanding of the relationships between all the various classes of modern society acquired through experience of political life.”

Of course, the working class does not need the communists in order to engage in U.S. political life. Spontaneously it already does so and even, to a certain extent, as a class. The organized trade union movement is clearly a mainstay of the Democratic Party. Its propaganda work, fund-raising and organizational efforts to bring workers to the polls on behalf of particular candidates play a definite and significant role in the electoral process. And a considerable number of workers do attempt to affect their own conditions of life by participating in the rites of election. In the absence of revolutionary leadership, of course, such activity amounts to spontaneous “trade union politics” and offers no long term prospects for emancipation of the working class.

Unfortunately, the state of the communist movement is such that its leadership at this point is limited almost exclusively to exploration alone. Given the present level of development of revolutionary forces, efforts at actively intervening in the bourgeois election process are qualitatively circumscribed. There is not a single party or organization of the left– using that term broadly–able to combine an advanced line with influence among the masses so that its efforts, whatever they might be, could in any way register some effect on the electoral barometer.

In that sense, the electoral gauge cited by Engels clearly demonstrates that in 1980 the political maturity of the U.S. working class is extremely low, precisely because the working class does not as yet have its own independent political expression.

This is even more conspicuous with the developing anti-revisionist, anti-“left” opportunist trend which is today incapable of mounting even a token independent effort in the elections. Nevertheless, we take up the question of the 1980 elections today from the standpoint of this trend. In doing so, we start with the assumption that it is necessary to rectify the general orientation of the U.S. communist movement toward bourgeois elections, recognizing that we are combatting a two-fold negative legacy: that of modern revisionism and social democracy which sows illusions either about one or another section of the bourgeoisie or the capacities of the electoral process itself; and that of ultra-leftism which, in its most classical form, disdains and will have nothing to do with bourgeois politics and, in a slightly more sophisticated form, participates in the elections in a formal sense by putting up candidates but does not take responsibility for guiding the working class through the twists and turns of independent political activity.

The present article attempts to contribute to the rectification of the communist movement’s orientation toward bourgeois politics by making a concrete analysis of the 1980 U.S. presidential election. Its principal focus is on the bourgeois parties since, at the present time, theirs is the only historically significant activity taking place in this arena. Nevertheless, the shadow of the class struggle–both domestically and internationally–hovers over the process and ultimately defines it. We undertake such a task because even in a period when the communists are without a party it is necessary to maintain a close surveillance over the political life of the country. Such surveillance is necessary to the forging of a general line which will provide the basis for re-establishing a communist party in the U.S. Further, the way in which we approach such political questions at the present moment itself begins to establish the theoretical, ideological and political underpinnings for the party’s future work in the bourgeois political arena.

In order to make such an analysis of the 1980 elections, it is necessary to reaffirm and amplify some of the basic propositions of the Marxist theory of the state. The first section of this article, then, takes up the theory of bourgeois elections and advances views in an implicitly polemical fashion with other approaches which have currency in the communist movement. The second section analyzes the 1980 election in the concrete, with particular emphasis on the bourgeoisie’s rehabilitation of Ronald Reagan, the failure of the liberal challenge in the Democratic Party and the less than meteoric rise and fall of the John Anderson “independent” candidacy. The final section briefly discusses the left and popular alternatives which presently exist, and advances some views on our movement’s future orientation toward electoral work.

The particular usefulness to the working class of bourgeois elections– particularly those in which the head of a capitalist state is “chosen” by the electorate–is that for a brief period general attention is focused on the question of political power. Naturally, the bourgeoisie does its best to obscure the question even while seeming to address it. But in doing so, it faces a dilemma.

On the one hand, the illusion that such elections can decide the question of power is one of the bourgeoisie’s most carefully nurtured myths, the basis for palming off the actual rule of capital as the workings of majority choice. At the same time, however, the bourgeoisie is periodically compelled to remind the masses that capital has imposed stern limits on what the masses may be permitted to choose. Thus the widely expressed complaint among the electorate this year after the Reagan and Carter nominations were assured–“What kind of choice have they given us?”–signifies a certain intuitive perception that someone (“they”) determines the parameters of the democratic choice.

But it would be extremely short-sighted for communists to glorify such spontaneously developed perceptual knowledge among the masses. In the absence of a scientific explanation of this phenomenon and a working class political alternative, common sense observations of this sort are more likely to herald a retreat from politics altogether rather than a move toward class maturity.

To begin with, then, let us reassert some of the fundamental propositions of the Marxist theory of politics and the state. In antagonistic class society based on exploitive economic relations which benefit some classes at the expense of others, political power is the capacity of one class to impose its will on another. The dominant political power of that society is invariably the power of the dominant economic class and is expressed principally through the state. That state is much more than the government; it is the entire bureaucratic apparatus of the state, its code of laws which establish and reinforce the prevailing property relations and the military power to enforce those laws. As Lenin puts it, “The state is a special organization of force; it is an organization of violence for the suppression of some class.” (State and Revolution.)

But the state is also more than a coercive institution. For the state, which comes into being only with the emergence of antagonistic social classes, and functions as the force which maintains and reinforces the relationship between those classes, is therefore at bottom a social relation. Just as the city-state of the Greeks came into being on the basis of the definite historical class divisions in ancient Hellenic society, so the modern bourgeois state is the expression of the relationship between the bourgeoisie and the other classes in capitalist society; most particularly, of course, between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat.

The chief characteristic of the state is as a public force, seemingly independent of the antagonistic classes, designed to maintain order. But since the state attempts to reconcile class antagonism on the basis of a definite system of actual property relations, the “order” that the state maintains is nothing but the suppression of one class by another. In earlier periods, this public power was relatively weak. “The public power grows stronger, however, in proportion as class antagonisms within the state become more acute, and as adjacent states become larger and more populated.” (Engels, Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State.)

With the growth of public power, represented in the first place by the institutions of coercion (standing army, police force, prisons, courts, etc.), the cost of maintaining the state increases rapidly.

The state has existed over the course of many millenia, ever since the earliest forms of society, which were characterized by the absence of class differentiation, gave way to class society. But it is only with the emergence of capitalist society that the state has become the powerful force we are familiar with today. The bourgeoisie brought into being the modern nation-state which, by encompassing large territories and providing the instruments of violence to enforce bourgeois property relations everywhere in the world that capital ventures, is the necessary political structure for the capitalist mode of production. In this sense, the bourgeois nation-state corresponds to the character of capital as an ever-expanding social relation, one which requires a broad and secure domestic and international market. It likewise corresponds to the competitive nature of capital, which itself requires a medium of mediation that, while in the service of no one sector of the capitalist class is in the service of all. And, most important, the modern bourgeois nation-state corresponds to the broadened and intensified nature of class struggle, ultimately simplified to the struggle between the two principal contending classes of contemporary society, the bourgeoisie and the proletariat.

In all these functions, the bourgeois state is founded upon, reflects and maintains the prevailing property relations of capitalist society. The bourgeois state, therefore, no matter what form it appears in. is nothing but the political expression of the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie.

A standard argument of social democracy and of revisionist theoreticians is that there has been a qualitative expansion of democracy unanticipated by the foremost Marxist theoreticians of the past, and that this development requires a revision of the Marxist theory of the state.

First of all, let us more closely examine the assumption underlying the argument. It is undoubtedly true that there has been a considerable expansion of bourgeois democracy ever since capitalism arose historically. A century and a half ago, for instance, access to the ballot was circumscribed by all manner of property restrictions and confined to adult males. (All this signified was that in the period before the bourgeoisie had fully consolidated its political and economic power, it was not about to permit the exploited classes to turn the bourgeoisie’s own political instruments against it.)

Since that time, virtually all legal restrictions to participation in the electoral process have been eliminated. No longer are there property qualifications. Women can now vote. In the U.S., all legal restrictions (and a considerable measure of the operational barriers) on the right of Blacks and other minority peoples to the ballot have been dropped. The legal age for voting has been lowered and in many areas of heavy minority concentration, literacy in English is no longer a requirement.

There has also been an expansion of legal rights in areas other than elections. Legally speaking, freedom of speech, press and assembly is today significantly less restricted than it was even 50 years ago.

But is the rule of capital today one whit shakier as a result of this expansion of bourgeois democracy? Has wider access to the ballot in any way brought about a firmer political challenge to the bourgeoisie even within the confines of the electoral system? Radicals may be able to say more inflammatory things in print today than was permitted in the past, but in no way has this development weakened the rule of monopoly.

It is not our intention to dismiss the significance of the gains in bourgeois democracy which have been won. Communists value these on two counts. First, every expansion of bourgeois democracy can be utilized by the working class not as the means of changing society but as the means of changing its own class consciousness. Second, the more bourgeois democracy grows the more does it become apparent that the problem confronting the working class is not a problem of the absence of certain legal rights, but the absence of actual power.

But the fact remains that the growth of bourgeois democracy has taken place solely in the context of strengthening of the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie. Indeed the former would not have been conceded without the development of the latter. Thus along with the expansion of bourgeois democratic rights has come the expansion of the state’s police apparatus and the development of a far more sophisticated machinery for repression than ever before. Along with the expansion of voting rights has come the ever greater significance of concentrated wealth in the manipulation of the political process. Along with a broader permissibility of expression has come a much more developed system of ideological controls in the hands of the bourgeoisie. (To paraphrase Anatole France, the law in its majesty permits any group of millionaires or any group of workers to open a steel mill, open a bank, or launch a television network.)

All this is what the uncritical enthusiasts of bourgeois democracy conveniently forget.

In addition, it is completely untrue that the earlier Marxists based their analysis of the bourgeois state on forms of bourgeois rule in which democracy had not yet reached its full flowering. Lenin, in fact, based State and Revolution much more on the model of the democratic republic than the Czarist autocracy. This is likewise the case with Engels’ Origin of the Family. Many communists are familiar with this latter work either through the brief excerpts quoted by Lenin in his work on the state or as a work which helps establish the materialist foundation for Marxist writings on the woman question, but do not sufficiently appreciate the extent to which Engels precisely analyzed the workings of bourgeois democracy.

“The highest form of the state,” writes Engels, “the democratic republic, which under our modern conditions of society is more and more becoming an inevitable necessity, and is the form of state in which alone the last decisive struggle between proletariat and bourgeoisie can be fought out–the democratic republic officially knows nothing any more of property distinctions. In it wealth exercises its power indirectly, but all the more surely. On the one hand, in the form of the direct corruption of officials, of which America provides the classical example; on the other hand, in the form of an alliance between government and stock exchange, which becomes the easier to achieve the more the public debt increases and the more joint stock companies concentrate in their hands not only transport but also production itself, using the stock exchange as their center.”

The instructive thing about Engels’ remarks is how well they anticipate those developments of capitalist politics which are so often cited as the reason for the need to re-examine the Marxist theory of the state. Far from being dazzled by the “expansion” of democracy which has led many a social reformer to conclude that the way has now been opened to a parliamentary transition to socialism, Engels notes that this form of rule is the “inevitable necessity” for the bourgeoisie. The full flowering of the democratic republic does not alter the tenacity of the bourgeoisie when its power is challenged, however; it merely (we do not mean to understate the significance of this “merely” since it lays the foundation for combining legal with illegal communist work) establishes the conditions under which the actual struggle for power proceeds. Engels likewise anticipates the enormous growth in the state bureaucracy (the rise in the public debt) and the further proliferation of monopoly by which the republican form of the state is ever more readily subject to the control of capital.

What makes the democratic-republican form of government an “inevitable necessity” for the rule of capital? The most common view among Marxists holds that this form provides the best instrument for tricking the masses. And undoubtedly bourgeois democracy performs this trickery well, for it allows the class rule of the bourgeoisie to project itself as the rule of, by and for the people for the first time in history. Legal barriers to formal democratic rights or property ownership disappear under a fully developed bourgeois democracy; so the image of a society not divided into classes can attain the figment of a material base.

The great myth of democracy is that in the democratic republic the ruling class is accountable to the masses. (By this standard, the masses have only themselves to blame if “their” leaders do not perform appropriately.) But the very nature of the democratic republic is to completely mystify the question of accountability. For in no way is capital legally accountable to the working class in terms of its economic decisions: and for every portion of the state apparatus which seems to be accountable to the electorate, there are a hundred other agencies, bureaus and institutions whose function is in no way determined by the elected portion of the state.

But all this deception is not so much the cause as the consequence of this form of rule. The bourgeois democratic republic is not and could not be such a consciously-designed plot by the bourgeoisie. Rather, the bourgeois democratic republic has developed into the best political shell for capital in a complex and historically definite manner.

What must be noted in the first place is that capitalism does not come into the world in its “pure” form, the step-by-step unfolding of the bourgeoisie’s ideal social arrangement. To the contrary, it comes into existence in the heat and as the result of intense class struggle. In seeking its own emancipation from the political and economic tyrannies of feudal society, the bourgeoisie opposes the existing political and ideological institutions thrown up by the feudal mode of production. As a result, its ideologists proclaim themselves the apostles of freedom, by which they mean freedom from every form of authority but one, the authority of private property. Thus, the democratic republic, which separates church and state and breaks the hold of the landed aristocracy on the government, becomes part and parcel of the bourgeoisie’s rise to political power. (In certain cases, where the prevailing form can be brought under the control of the bourgeoisie–such as England’s limited monarchy– capitalism can maintain the outmoded political form and force it to serve the needs of the bourgeoisie.)

Nevertheless. whether in its American constitutional form or’ the European parliamentary form, there is indeed a considerable measure of freedom in the democratic republic; for capitalism requires an atmosphere of liberty, meaning the liberty of private wealth to make whatever economic decisions it deems advisable on the basis of self-interest. To guarantee that the fierce competition between the capitalists themselves does not result in unrestrained cannibalism to the detriment of all, the bourgeoisie likewise requires some “neutral” regulator of its common affairs. To assure the relative neutrality of this instrument, the bourgeoisie requires a code of laws and a number of institutions backed up by military force which, while designed primarily to maintain the rule of capital over the workers, also establish checks against any one sector of the bourgeoisie seizing the state apparatus for itself.

Likewise, the democratic republic is most conducive to the existence of a market in “free” labor, that is of workers who have nothing to sell but their labor power. The variety and sophistication of the tasks which this class of laborers must perform requires a general raising of the cultural level of the masses. Free public education is a demand advanced by the workers but which is ultimately readily granted by capital because an educated proletariat is needed to both produce and consume the variety of commodities of which capitalism is capable. At the same time, capitalism’s “marketplace of ideas” (the terminology is more than a happy coincidence) reflects both the commodity nature of intellectual life and the fact that freedom of expression is fundamentally the freedom to make available for sale a variety of intellectual products in the bourgeois marketplace.

Clearly we have hardly exhausted the Marxist theory of the state in noting the above propositions. But these are sufficient for our purpose, which is to demonstrate that the modern bourgeois state is nothing but an instrument of class rule and, in today’s circumstances, an incredibly powerful instrument on behalf of the greatest accumulation of wealth in all history. Therefore, to suppose that U.S. finance capital, sitting astride this concentration of political power which defends its economic power, would subject its rule to the vagaries of a popular election is to make the tales of Hans Christian Anderson scientific treatises in applied physics.

In fact, the bourgeois state is quite impervious to the electoral process.

In the U.S. version of this system, the branch of government with the least degree of power–the Congress–is the one most easily penetrated by the other classes. Even within this construct there is a convenient distinction. The House of Representatives functions as the medium for a united front under bourgeois hegemony between monopoly capital on the one hand and small capitalists, the petty bourgeoisie, and the labor aristocracy on the other. The Senate, having much more power, is a more stable institution, not even subject in its majority to the vagaries of a popular vote in any given election.

The Presidency is a much more powerful institution. Through this chairman of the bourgeoisie’s executive committee, monopoly capital must take all of the necessary steps to meet the contradictions constantly besetting it. This is the key post. The President’s actual powers–those conferred on the office by the Constitution and those systematically appropriated to the office by the most energetic representatives of capital–are enormous, particularly with its direct control over the military and police apparatus and likewise its control of the government’s purse. At the same time, there are a series of fail-safes that impose objective limitations on what the president can and cannot do. The entire executive establishment, most of which is not subject to the changing winds of the electoral process, is itself a reflection of the state as a social relation of capital–tied to the giant corporations and banks by considerations of personal career and ideology (and always subject to the displeasure of the most powerful sectors of capital)–which guarantees that in practice all laws and regulations, no matter what their content, are implemented on behalf of capital.

In addition, the judicial system operates as the bourgeoisie’s court of last legal resort. Here the very pillars of bourgeois rule, themselves not accountable even in form to the masses, are able to function as the guardians of the bourgeoisie’s social contract with the proletariat.

The actual political significance of the U.S. electoral process can only be comprehended in this framework of the actual working of bourgeois rule. In this context, any projection of an election as a device which could alter the essence of class rule becomes an obvious charade. But it hardly ends there. Equally specious is the view that sees momentous issues of policy even within the framework of bourgeois power being determined at the nation’s ballot boxes on the first Tuesday of every fourth November. To hold such to be the case is to believe that a U.S. bourgeoisie which has gone to great pains in order to ensure its control over society’s legal institutions would permit the masses, through their votes, to settle the complex questions of policy by which capital defends both its power and its wealth.

(Let us, however, be very clear on the fact that the class struggle can and does affect, modify and alter the actual policies which the bourgeoisie pursues and that it is completely capable of wresting significant concessions from capital. But that struggle is not conducted primarily through the bourgeois electoral process, although an election may well turn out to be the form through which the intensity of that struggle is registered and provide the instrumentality for making whatever concessions are deemed appropriate.)

Any review of U.S. political history readily confirms the fact that elections, at least since the Civil War, however much they may be the instrument through which bourgeois policy changes are realized, are not themselves decisive in the formulation of such changes.

Has there been a single U.S. presidential election campaign in this century in which the general course of events would have been significantly altered had the presidential election verdict been reversed? Would the election of Charles Hughes rather than Woodrow Wilson in 1916 have kept the U.S. out of the great imperialist holocaust of World War I in defiance of the compelling needs of U.S. capital for an allied military victory? Would Al Smith have prevented the onset of the depression or been able to deal with the human misery it produced more effectively than did Herbert Hoover? Franklin D. Roosevelt’s bold measures to maintain social peace in the early thirties may have drawn the verbal fire of some ruling class ideologists, but the lop-sided election of 1936 demonstrated that monopoly capital was more than satisfied with the accomplishments of the New Deal. Would the Cold War not have been launched, the Taft-Hartley law not enacted or the leaders of the U.S. Communist Party not indicted had Thomas Dewey rather than Harry Truman been President of the U.S.? What would have been different about the 1950s if they had been known as the “Stevenson years” rather than the “Eisenhower years”? Lyndon Johnson, it should be recalled, was elected in 1964 by labelling Barry Goldwater the “war candidate,” although plans for U.S. military intervention in Vietnam were already far advanced. The principal issue at stake in the 1968 election was who would end the war in Vietnam, Nixon or Humphrey. The policy decision had already been made by Lyndon Johnson’s abdication and a ruling class consensus had concurred in it.

And when in the course of these agonies the bourgeois political process brings to the fore candidates who betray a tendency to become hostage to their electoral base at the expense of the interests of capital, no matter whether their loyalities are accorded to the left or the right, the bourgeoisie has other means for handling the situation. Thus, in 1964 the responsible sections of finance capital, (responsible to their long range class interests), deemed Barry Goldwater an unacceptable candidate. Consequently, they first did everything they could to block his nomination by the Republican Party. When this effort failed, his candidacy was simply undercut, resulting in a massive electoral victory for Johnson. The dominant sectors of the bourgeoisie, represented by Nelson Rockefeller and the “Eastern Establishment,” were unhappy with Goldwater for two reasons. First of all, he won the nomination through the efforts of a rightwing political base within the Republican Party and he gave every sign of being more accountable to that base than to monopoly capital itself. Even when the immediate political program required by capital coincides with that of such a base (it could as easily be left-liberal under other conditions), the bourgeoisie requires at the helm of its state individuals who look at the contradictions of the system all-sidedly. Conservatives must indicate their sensitivity to the uses of reform and tactical concession in the interests of social peace. Liberals must demonstrate that they can be tough with the masses when necessary (Kennedy’s sponsorship of the modified version of S.I., the criminal reform bill, was designed to meet this political need.) Anti-communists must make clear that they are ready to negotiate with and even make concessions to communist countries when it is in the interests of the bourgeoisie to do so, just as reformers and the architects of more sophisticated forms of neo-colonialism must be prepared to beef up the military budgets and employ the armed forces when necessary. Goldwater was seen as too much of an ideologue to be able to make the necessary accommodations to the bourgeoisie’s need for flexibility of response, especially in light of the treatment accorded Nelson Rockefeller at the Republican convention and the designation of an unknown right-wing congressman as the vice presidential candidate. (Ronald Reagan, as we shall see, handled this dilemma far differently and as a result was himself treated differently by the Rockefeller section of finance capital.)

More particularly, the ideological stance and concrete policies associated with Goldwater were deemed inappropriate for 1964. His conservative domestic policies were sure to exacerbate the already intensifying contradictions brought to the surface by the Black freedom movement. Even on Vietnam, the bourgeoisie’s consensus was based on the concept of “limited war” for fear that an all-out confrontation with both China and the Soviet Union in an Asian land war was not the right war at the right time for U.S. imperialism; Goldwater, on the other hand, gave no evidence of understanding the nuances involved. In addition, it seemed certain that the only way to make this war palatable to the masses in the U.S. was to have it conducted by an administration committed to keeping the social peace through a “guns and butter” policy in relation to the working class and appropriate legal and ideological concessions to the Black masses. Such a stance was clearly more suitable to Johnson and the Democrats than the Goldwater wing of the Republican Party.

It was this combination of ideological and political factors that did Goldwater in. Ultimately, Wall Street’s appraisal of his candidacy was telegraphed by Rockefeller’s boycott of the campaign effort and an ideological undercutting of the Goldwater candidacy that produced a massive Johnson victory at the polls.

A similar point is to be made concerning the Eugene McCarthy effort in 1968, in which the responsibility of managing the U.S. defeat in Vietnam was not to be left to a maverick senator from Minnesota whose political history was such that he could not be seen as appropriately accountable to monopoly capital. This was true, even though he had done the system a good turn by anticipating its political needs and offering the masses a lightning rod that would bring their anger back into the bourgeoisie’s legal apparatus. The political question at that point was not ending the war, but how it would be done.

The essence of these phenomena, however, cannot be grasped at the empirical level. Nor is the relationship between monopoly capital and the electoral process a simplistic one in which a designated representative of the titans of investment banking notifies the national committees of the two major parties of the names of the candidates they are to nominate.

The process, in fact, much more closely resembles the workings of the bourgeois marketplace. The various political figures who make up the pool of those to whom the reins of state will be entrusted bring their product–themselves–to market over the course of time, attempting to demonstrate through their political careers their capacity to serve the bourgeoisie while maintaining sufficient credibility with the masses (or a significant section) to keep getting elected to office. The likelier candidates build up a fairly sizeable entourage, each of whom has an appropriate stake in the enterprise, over the course of time, so that ultimately the bourgeoisie selects not just an individual but a fairly cohesive team, unified around its leading personality, to whom it will entrust political power. It is hardly an accident that this process has been described as the real American Beauty contest, easily overshadowing in interest and significance the sexist anachronism annually staged along the boardwalk in Atlantic City. The complexity involved is that the parading aspirants are strutting their stuff for two audiences– the electorate (as registered not only in primaries but in popularity polls and general image) and monopoly capital. Since it is monopoly capital’s choice which is decisive (the electorate only chooses after capital has winnowed out the field), let us examine its considerations in finding a candidate acceptable.

First, the candidate should be a significant national political figure. While occasionally an “outsider” is deliberately promoted, confining the pool to those who have been in the public spotlight for a lengthy period of time means that those who have made it thus far to the top of the political heap have undoubtedly demonstrated already in a thousand different ways their sense of responsibility and fidelity to the needs of monopoly capital; and indeed, the majority probably are directly indebted to one or another sector of capital.

Second, the candidate should represent a general political/ideological image that is in tune with the particular needs of the bourgeoisie at the given moment. Paraphrasing Ecclesiastes, for the bourgeoisie there is a time for war and a time for peace, a time to grant concessions to one or another section of the masses and a time to take those away, a time to demonstrate the “openness” of government and a time to show the mailed fist. And for each of these times there is a candidate. Thus, in a time of great social unrest, the candidate must be able to represent a means of securing social peace, whether through carefully conceived concessions to the masses, the use of repressive measures, or a combination of the two, depending on the precise combination deemed most advisable at the time.

Ideally, the bourgeoisie would prefer to have its pool of available talent made up exclusively of pragmatic technicians who would simply effect whatever policies are called for with no pretense of having any other views than those that serve the best interests of U.S. imperialism. But the third requirement for a candidate–the necessity to secure a popular base, maintain credibility among the masses, and win elections, requires of every politician, no matter how pragmatic, an image based on a set of beliefs which seem to be independent of the vagaries of the needs of the bourgeoisie. To be sure, these beliefs are rarely if ever operative in office. But they are essential to winning an election and legitimizing the state apparatus in the eyes of the masses.

Not every bourgeois politician with a popular base whose general stand on immediate questions corresponds with the needs of capital is acceptable to the bourgeoisie, however. Here the final requirement is introduced that ultimately separates the amateurs from the professionals in bourgeois politics. That is, while maintaining a sufficiently strong image to keep whatever political base they have in line, the professionals will clearly indicate that they are treating their supporters tactically and dealing with finance capital strategically.

In short, every would-be wielder of power in the bourgeois political process must be acceptable to the major sectors of finance capital while maintaining a sufficient degree of credibility among the masses. Of these, the approval of finance capital is principal. Credibility and name-recognition may be important, but there are ways of manufacturing it if necessary (Jimmy who?). The never-ending ballet to balance these considerations constitutes the essential choreography of modern bourgeois politics.

The bourgeois state can never be, ultimately, anything but the form through which capital exercises its dictatorship in society. But as an institution the state takes on a certain life and logic of its own which, at times, may even run counter to the consciousness of the principal sectors of the bourgeoisie.

There are several reasons for this. The first lies in the fiercely competitive nature of capital itself. The state rules on behalf of capital as a whole, but as Marx pointed out, “capital exists and can only exist as many capitals,” (Grundrisse), and therefore the task of ascertaining what policy is in the common interests of these many competing capitals is far from a simple one. The solution to it can hardly be tied to the interests of one or another grouping of capitalists and therefore, the bourgeois state, operating on behalf of the capitalists as a class, will of necessity be relatively independent of any one sector of the class.

Second, the intensification of class contradictions under capitalism has resulted in an enormous growth in the public power. The state’s coercive institutions today are far more extensive than they were in an earlier age, represented chiefly by the growth of the military establishment and the incredible expansion of the police apparatus. In addition, the art of maintaining the social peace has brought into being a swollen bureaucratic machinery numbering in the millions, charged with carrying out a variety of ameliorative measures designed to calm the masses. It would indeed be surprising if this general expansion of the state apparatus did not provide its principal mentors with additional leverage in the general social dynamic and in their relations with capital itself.

Third, the increasing irrationality of capitalist production has invested the bourgeois state with new responsibilities for intervening in the economy–as employer itself, as caretaker of precarious sectors, as regulator of capitalist cannibalism and as a collective banker of last resort.

Finally, the operational financial and political leadership of the bourgeoisie is rarely identical. Nelson Rockefeller being the exception that proves the rule. But for the most part, the actual holders of wealth do not find it either necessary or convenient to play a direct role in the management of the bourgeoisie’s political power.

For all these reasons, the bourgeois state apparatus functions with a measure of independence from the immediate direct dictates of capital. However, the significance of this flexibility, without a grasp of which there can be no firmly rooted understanding of the actual political motion of modern society, has been seriously distorted by much of the communist movement.

The most obvious distortion has been that which oversimplifies the relationship between the state and the bourgeoisie. With a blithe disregard for the many injunctions by Marx and Engels against any tendency toward economic determinism, one common prejudice of the communist movement has been simply to see behind every political development the direct and conscious hand of capital. Such a view ignores two readily demonstrable propositions: one, that the competitive nature of capital means that the bourgeoisie can only infrequently particularize its common class concerns with generally agreed upon policies and personalities; and two, that the bourgeoisie is not an omniscient class with ready-to-hand answers to its array of afflictions.

Accordingly, the state necessarily acquires certain freedom of action in confronting and trying to resolve the numerous contradictions which are the fate of capital.

When the theoretical complacency underlying this distortion is translated into a program of communist politics, its results are pathetic parodies of Marxism which in fact surrender the task of educating and training the working class to an understanding of the actual motion of politics and the class struggle.

Nevertheless, this obvious distortion is not the most serious deviation from the Marxist theory of the state on this question. In fact, such amateurish dogmatism serves principally to provide a convenient foil for the opposite error which, presenting itself as a theory of “the relative autonomy of the state,” actually separates the bourgeois state from its class moorings altogether. Such views, essential to the political perspective of Eurocommunism, have been given their most developed theoretical expression by the late Nicos Poulantzas.

According to this theoretical school, while the modern bourgeois state may have developed as an instrument of the capitalist class (and this is by no means universally conceded), its own laws of development have brought us to the point where the massive power inherent in the state is by no means the exclusive property of one or another class. The struggle for state power, according to such theories, can then take place within the state itself; more particularly, the parliamentary struggle for direction of the government can thus become capable of actually settling the question of political power in class society.

Such a view abandons the standpoint of materialism for it invests in the form of political power its essence. Bourgeois parliamentary democracy is held up as the ideal representation of the proletarian as well as the bourgeois state rather than as a historically evolved form based concretely on the political needs of capital. In the real world of politics, such theories distort or ignore the actual workings of the class struggle on two counts: first they fail to grasp the power of capital ultimately to impose its will on the political arena, not through the rhetoric which surrounds it but in the actual results it is able to achieve; and second, they have not understood how the increased internationalization of capital has likewise given bourgeois political power an international character which was more than adequately summed up in the infamous comment by Henry Kissinger in developing U.S. imperialism’s response to the election of the Salvador Allende government in Chile: “I don’t see why we need to stand by and watch a country go communist due to the irresponsibility of its own people.”

Speaking in the most practical terms, it is nothing short of ludicrous to assert that the U.S. imperialist state is somehow up for grabs through the bourgeoisie’s electoral process. It is certainly true that in the U.S., growth in the state apparatus has given to those who manage it directly enormous power to influence the course of events, as a result of which they now hold an increased measure of leverage in their relations to any particular sector of the monopoly capitalist class. But precisely because of the extent of this power and the size of the state apparatus, the bourgeoisie has seen to it that the myriad threads by which the state is bound to capital have been reinforced a thousand-fold through a system which goes far beyond classical influence-peddling, bribery and corruption.

To a certain extent, the confusion on this question results from the fact that the state in recent times has increasingly become the medium through which the bourgeoisie mediates its concessions to the masses. In an earlier period, the task of buying social peace was largely left to private capital operating through the wage system and philanthropy. But the massive economic concessions required today to maintain social peace are, in many respects, beyond the capacity of the private sector. Welfare, food stamps, unemployment insurance, social security, minimal forms of health insurance (Medicaid, etc.), subsidization of education, low-cost housing developments (such as they are) and numerous other reforms are now the domain of the state. Far from indicating any weakening in the bourgeoisie’s control over the state apparatus, the “welfare state” actually demonstrates the ever-firmer control of the state by monopoly capital.

The capacity of this executive committee of the capitalist class to represent the interests of the class as a whole at certain key junctures of the class struggle is clearly an advance over the earlier periods when there was much less “science” to the process. And the artful linking of concessions to the coercive apparatus has enabled the state to bring capital itself into line in actions which, while for its own good, are not always perceived that way by the individual proprietors of capital. In addition, the deepened link between reform and repression has enhanced the ability of the state to orchestrate the dialectic between the two while imposing definite limits on the concessions themselves.

At the heart of the process is the fact that the management and administration of the bourgeois state apparatus is itself a point of class definition, made so not by the intentions of those who manage the state but by the social relation which the state expresses.

As a result, the actual relationship which prevails today between the bourgeoisie and its own political representatives is one in which the state is more than a servant but less than an equal partner with capital in determining the various policy questions which confront the ruling class. On matters of tactics, the guardians of the state apparatus enjoy considerable flexibility; on matters of strategy, very little; and on matters of ultimate class rule, absolutely none.

For the 1980 presidential elections, the bourgeois electoral marketplace has produced a rather dismal array of commodities. The Republicans have turned to an aging second-rate movie actor whose principal point of ideological identification appears to have been somewhat inadvertently registered by the candidate’s expressed doubts on Darwin’s theory of evolution. (The more charitably inclined believe that the candidate, who admits to have become somewhat hard of hearing, thought that his questioner was asking about the theory of revolution rather than evolution.)

The Democrats, on the other hand, could find no convenient way to disencumber themselves of a president whose standing with the electorate had sunk to the point where Richard Nixon, on the eve of his pending impeachment, enjoyed a greater measure of confidence among the citizenry. Trying to be a conservative Democrat in the White House, Jimmy Carter has not been conservative enough for the Republicans but has drifted too far right for key sections of the Democratic Party whose base in the working class and among minorities requires a greater fidelity to ameliorative reform than Carter has been capable of offering.

Given what even that Rock of Gibraltar of bourgeois ideology, Time magazine, called a “Hobson’s choice” between two candidates who rival each other principally in the extent of their lack of credibility with the masses, it is not too surprising that a third commodity should be offered for sale. Representing no coherent philosophy but his own ambitions, Congressman John Anderson can hardly be faulted for making himself available to the bourgeoisie in a year in which the normal workings of the two-party system appeared to have left monopoly capital with somewhat grim alternatives. But Anderson’s offer of himself as a better mousetrap does not appear to have made a dent in the widespread electoral apathy clearly visible among the voters.

As late as midsummer, the New York Times was noting that “the most obvious motto for the 1980 Presidential campaign so far is still ’None of the Above’.”

But voter frigidity toward their candidacies is not all that Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan have in common. While each regales the public with dire warnings of the calamities certain to follow upon the election of his rival, the current dilemmas of U.S. monopoly capitalism and the low level of class struggle at home make it rather obvious that the course the U.S. bourgeoisie will pursue over the next four years will not be significantly different no matter who occupies the White House.

Every U.S. presidential election is framed by the particular contradictions internal to monopoly capitalism which have come to the fore at a given period. Although no neat categorization into “domestic” and “international” problems does justice to the interpenetration of these contradictions, in general this distinction operates as an effective means for both official political debate and Marxist analysis. In times of rising social turmoil and class struggle, the policies and measures required to restore social peace at home–whether reform or repression–occupy the attention of the bourgeoisie and its political representatives. In periods when the challenge to bourgeois hegemony is located principally in the international arena–whether from inter-imperialist rivalry or the advances of revolutionary forces in other countries–then the attention of the bourgeoisie is riveted on those policies required to repel the challenge.

In 1980, the contradictions confronting the U.S. bourgeoisie are concentrated in two areas: the deteriorating state of the U.S. economy and the rising global challenge to U.S. hegemony internationally. Meanwhile, the U.S. working class, while increasingly disenchanted with bourgeois politics, appears to be characterized more by a state of resignation than one of militancy, a condition which cannot be solely attributed to the absence of a viable left alternative. Of course, the bourgeoisie cannot afford to view the relative calm in the class struggle at home as permanent. The more knowledgeable are aware of the fact that an elaborate (but costly) structure of social reforms, economic benefits, tokenist political concessions and the hold of the bourgeois ideology over the working class is indispensable to the continued maintenance of the present social peace. But the extent to which the price for maintaining this situation can be reduced–not just in dollars but in political matters–is itself one of the principal debates within the bourgeois political structure.

Accordingly, the great “issues” of the 1980 election campaign are focused around economic questions and the state of U.S. foreign policy. But, as we pointed out earlier, the two-party system generally operates in such a way that despite the heated debates over policy and direction that take place during election campaigns, the actual policies pursued by whoever wins the election are rarely different in any significant way. Marxists are hardly unique in pointing out this much. An astute conservative political commentator, Reagan supporter James Kilpatrick, noted as much: “If we look at what the two parties do as distinguished from what the two parties say, the two-party system is a joke.”

Nowhere is this more readily apparent than on the two main questions which have come to the fore in the 1980 elections.

Thus, on the question of the economy, the Wall Street Journal (July 1, 1980) notes the judgment of Alan Greenspan, chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Ford, that “from an economic policy standpoint, it doesn’t make a great deal of difference whether Ronald Reagan or Jimmy Carter wins the presidential election in November.”

Meanwhile, on the other great issue of this election, foreign policy, the correspondent of the Christian Science Monitor, Joseph Harsch, points out (July 18, 1980) what is also widely perceived: “This is a good time to remind foreign policy observers in the U.S. and diplomats overseas that they need not wring their hands in despair over the things being said on the American hustings during this current political season. If one did try to forecast the future of U.S. foreign policy from current speeches, one would have to assume that a Reagan administration taking office in January of next year would immediately and drastically alter the course of U.S. policies toward the outer world. In fact, there might be some changes in declaratory policy, but probably negligible, if any changes in actual operating policies.”

What gives additional weight to these summations is that the first comes from a Republican whose party has launched an all-out attack on current economic policies and the second comes from an observer of a generally liberal bent on international affairs who would tend to be particularly concerned about any shift toward an “irresponsible” U.S. foreign policy.

Let us, then, more closely examine the actual content of these policies. In relation to the problems confronting the economy, the magic phrase of the moment is “reindustrialization.” First popularized by conservative Republican congressman Jack Kemp a few years ago, the term has now been adopted on all sides of the bourgeois political spectrum. What does it mean?

Basically it involves a conscious attempt on the part of government to shore up the deteriorating economic position of U.S. monopoly capitalism in relation to its capitalist rivals and to remove various restraints on capital’s freedom of movement won in the course of class struggle over the past decades. The watchwords for “reindustrialization” are “economic growth,” “capital formation,” “worker productivity” and “tax reform.”

The theory behind it all is that the economy can only be rescued from its woes by a cross-class recognition that the well-being of all is dependent on the well-being of capital. The working class will be entreated to join in the writing of a new “social contract” in which economic demands will be subordinated to the common goal of getting U.S. industry back on its feet. As one commentator notes, “without a solid industrial base, there can be no surplus to support environmental needs, the poor, the minorities.”

Meanwhile, annoying restrictions on capital such as regulations designed to protect worker safety and the environment would be removed and the agencies responsible for their enforcement (such as it has been) would be dismantled.

A broad array of tax reforms would be enacted. These supposedly would encourage capital formation by lowering taxes on corporate profits and on the wealthy in general so that more money would be available for long term investments. Special additional tax breaks for research and capital investment would be part of the package.

While there are differences between the candidates on exactly how this broad policy would be implemented–differences which speak in part to somewhat different ideological orientations based on the various constituencies to which the candidates are responsive–the general direction of U.S. economic policy will be more oriented than previously to a governmental role designed actively to provide smoother sailing for capital.

Concerning foreign policy, the differences between the candidates are even more miniscule. The Carter Doctrine of more aggressive counterrevolutionary activity in the Middle East and elsewhere, a policy which could well be labelled “The Empire Strikes Back,” enjoys an overwhelming ruling class consensus. The principal concern in the U.S. foreign policy establishment would appear to be the prospect of a growing link-up between the anti-imperialist liberation struggles in the colonial and neo-colonial world and the socialist countries. U.S. imperialism’s view seems to be that without Soviet ”intervention,” it can successfully manage most of the contradictions in the empire so that the rule of international capital will be secure even though its political forms may alter.

In such a context, a military edge over the Soviet Union becomes essential. The threat of a last atomic resort against the USSR is seen as the necessary leverage in order to keep the Soviet Union from “meddling” in imperialism’s affairs.

The “debate” between Carter and Reagan on this question is a farce. Reagan charges Carter with having weakened the U.S. militarily and waking up too late to the “Soviet threat,” when it is perfectly clear that the President has done yeoman service on behalf of the bourgeoisie on this question, having managed the transition from paralysis caused by the Vietnam debacle to a stand of increased military spending and war preparations. Carter, on the other hand, charges Reagan with being “trigger-happy” while flaunting a new U.S. policy of “limited” atomic war (thus greatly enhancing the possibility of an atomic conflict) and readying military provocations in the Middle East.

But if the differences between Carter and Reagan are indeed so specious, what is the election campaign all about anyway? The heat engendered cannot be ascribed solely to the playing out of an already written scenario.

For the working class, the 1980 presidential election in the U.S., like its predecessors, is undoubtedly a stacked deck, one more elaborate charade which can in no way alter or modify either the underlying property relations of the capitalist system or the actual policies that the bourgeoisie will pursue over the next four years. But the precise way in which this deck is stacked, the basis for the political rivalries within the bourgeois camp, the way in which the specter of the class struggle hovers over even such otherwise meaningless exercises in politics as a bourgeois elections–these are all questions which should be of consummate interest to all class conscious workers. For these all provide the window into U.S. politics by which the motion of all classes can be gauged and against which the working class can frame its own independent motion.

Let us, then, more closely examine the actors in this political dumb-show.

Two things stand out about the Republican Party in 1980: Ronald Reagan has become acceptable to finance capital; and the “new right,” the ideological fore-runner of U.S. fascism, has expanded its beachhead in the Republican Party.

The transformation of Ronald Reagan from a candidate who, in 1976, was unacceptable to the key sectors of finance capital into a contender in 1980 who has become acceptable to those same sectors has come about as the result of two closely connected developments: a consensus in the ruling class concerning the policy options it presently deems most desirable which more closely approximates the general ideological image projected by Reagan; and candidate Reagan’s conscious repositioning of himself in such a way as to make clear that while he maintained obligations to his political base on the right, his relationship to that political base (and its ideology) would henceforth be tactical and his relationship to finance capital would be strategic.

Reagan, like Barry Goldwater before him, has never been a favorite of the dominant sector of finance capital–sometimes known as “the Eastern Establishment.” The titanic battles within the Republican Party over the past 40 years have all essentially revolved around the conflict between finance capital’s desire for a “responsible” presidential candidate capable of political flexibility in serving the interests of monopoly and conservative ideologues more concerned with “principle” than results. Wendell Willkie, Thomas Dewey, Dwight Eisenhower, Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford–these have been the preferred choices of finance capital in the maelstrom of Republican Party politics while the likes of Robert Taft, Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan have always been viewed as outsiders of somewhat dubious reliability–even when their platforms were in no way distinguishable from the favorites of Wall Street.

The reason is simple. Ideologues–even of the right–tend to lose sight of the political realities, especially when the times call for bold initiatives and tactical retreats. Would a Goldwater or a Reagan have been able to wind down the Vietnam War or make the opening to China? Probably not, but Nixon could. Finance capital cannot always prevent some ideologue from capturing a party’s presidential nomination; but then it has other means at its disposal, as witness the overwhelming election victories of Lyndon Johnson over Goldwater in 1964 and Nixon over George McGovern in 1972.

Until recently, Reagan was considered unacceptable to the mainstream of finance capital. When the former governor of California decided to make one last try for the presidency in 1980, finance capital once again sought an acceptable alternative. A number of politicians, anyone of whom would have been preferable to Reagan, put themselves on display, among them Howard Baker, George Bush, John Connally and John Anderson. In the end, after each had faltered, a last desperate effort was made to revive the hopes of former President Gerald Ford, but by then it was too late.

The Reagan of 1980, however, had learned something from the past. From the beginning he artfully began to position himself away from his right wing political base. The process required considerable delicacy, because Reagan needed the right to win the primaries, but he also needed to demonstrate his pragmatism to the real power brokers on Wall Street.

By March it seemed as though Reagan’s march to the nomination could not be stopped. It was at this time that the investment banking establishment opened a fascinating public dialogue with him, the burden of which was to inform Reagan what it would take to win their approval. Particularly revealing was an editorial in the Wall Street Journal (March 13,1980), aptly entitled “Learning to Love Ronnie,” itself a clear signal that if he played his cards right, Reagan could get the endorsement of the party’s center this time around.

Noting Reagan’s growing lead in the delegate count, the Journal posed the following question: “Why do so many people who agree with his positions still find themselves unenthusiastic about his candidacy?” The Journal answers with great candor. The Republican establishment is concerned that Reagan may be another Goldwater, a rightwing extremist.

“In a way,” says the Journal, “this is unfair, since the nation has clearly moved toward Mr. Reagan’s longstanding positions; Mr. Goldwater’s too. . . . But in another way, the concern about Mr. Reagan being ’too far right’ comes close to the mark. He is, for example, the current champion of those who view the burning issues of the day as opposing gun control, making abortion unconstitutional and outlawing homosexuality. There is something to be said on behalf of these people; they correctly sense that these issues are raised as part of a broader attack on American society. But a President who spends much time on such issues, or partakes of the simple sloganeering in which they are debated, is not likely to deal very well with the realities of a complex world. And often, as in making the Panama Canal the linchpin of American foreign policy, Mr. Reagan has indulged these supporters rather than educated them. It seems to be happening again in this campaign with the poor Trilateral Commission, a group founded by David Rockefeller to promote American-Japanese-European understanding. . . . In a loose sense, we suppose, the Commission can be used as a proxy for criticizing an Eastern foreign policy establishment that suffered a failure of nerve over Vietnam. But it’s ugly when this gets articulated as a conspiracy to sell out the Republic and used in New Hampshire against Mr. Bush, a former member.” (Emphasis added.)

From that point on, there was a noticeable although subtle shift in the Reagan campaign. The simple-minded one-liners so much adored by Reagan’s rightwing base were still there–(“I don’t believe that freedom of religion means freedom from religion”; “the U.S. government’s present definition of a family is ’any two persons living together’”)–but now there was a new tone indicating that ideology wasn’t policy and that the concerns of capital might well require other than simplistic answers. To indicate that he recognized the complexities of maintaining social peace, Reagan began more and more to establish his personal affinity with Franklin D. Roosevelt. Increasingly his attack was on governmental waste in the managing of social programs, not on the programs themselves. The Panama Canal receded into the background, to be replaced by the call for renewed military strength. The attacks on the Trilateral Commission were quietly dropped.

By the time of the Republican national convention, the Wall Street Journal was ready with its new assessment of the candidate. “It is plainly to Mr. Reagan’s credit that our political system now reaches out to him. . . . Events seem out of control, and in ways very like those about which Mr. Reagan has for so long warned. . . . One would wish for a younger, more experienced and more profound candidate to express the sentiments Mr. Reagan has tapped. But who would it be?” (July 14, 1980) (Emphasis added.)

While these words were being weighed in the centers of finance capital, a parade of “Eastern Establishment” luminaries mounted the rostrum in Detroit to signify that Reagan had passed the test. One after another, Gerald Ford, Henry Kissinger and George Bush–much to the apparent discomfort of Reagan’s rightwing base–came to formalize the annointment. And Reagan did his part in return, accepting Bush as his vice-presidential running mate, an offering to finance capital that takes on added significance in light of Reagan’s age and the definite possibility that, if elected he would be a one-term president.

But while Reagan has thus become acceptable to finance capital, it cannot be said that the most powerful sectors of the ruling class are particularly enthusiastic about this candidate. There still exists a certain uneasiness about Reagan in the ranks of capital, nowhere more evident than in the delicate negotiations which almost brought Gerald Ford onto the Republican ticket. For the ”demands” made by Ford’s supporters in the heady hours of trying to formulate the “dream ticket” were principally a probing action by finance capital’s most responsible representatives (only Kissinger could have played so central a role in such a process) to see how much Reagan’s actual political power might be curbed and placed in more reliable hands. In the end, the scheme failed; but the effort itself was the most revealing part of the episode.

The significance of Reagan’s candidacy, however, does not end there. For Reagan’s triumphal march through the primaries, along with the political platform adopted by the Republican convention, indicates that the rightwing has expanded its beachhead in the Republican Party and has probably become the dominant political force within it. In light of the extent to which the particular political form that suits U.S. monopoly capital the best is the two-party system, this development means that fascism has now secured a more advanced base in U.S. politics than ever before.

Here let us pause for a moment to counter the prevailing prejudice on the left which sees fascism simply as the creature of monopoly capital. Ultimately, the turn to fascism is dependent on the acquiescence of capital. It is likewise true that sectors of monopoly capital are constantly financing fascist-like political groups. But politically, mass fascist movements most often develop somewhat independently of–and sometimes in direct opposition to–the mainstream of capital. In fact, their initial appeal is principally populist, attributing the felt anxieties of the masses to an unlikely combination of communists and bankers. Fascist movements come into being precisely at those historical moments when the crisis of capitalist economics gives rise to a general political, social and moral disorder in society. While this is a period in which the working class becomes most capable of developing its revolutionary consciousness, other sectors of the population–the petit bourgeoisie, backward sectors of the working class and groupings within the ruling class–yearn for a return to stability. Freedom becomes less important than order. Stability is associated with former days of glory when all people knew their place; racial and national minorities “accepted” their lesser status; women were not ony subordinate to men, but all acknowledge that this was the proper order of things; hard work was its own reward; and all decent folks loved their country.

Exploiting these anxieties, fascist movements develop a political base which is not dependent on the approval of monopoly capital, but then make themselves available to capital at a certain moment when the class struggle brings the system to the edge of a political crisis and the dominant sector of capital is then prepared to abandon its own “best political shell” of bourgeois democracy in favor of the more naked repression of fascism.

In this sense, the positioning of U.S. neo-fascists in the heart of one of the two major political parties is an event of considerable historic significance. For under such circumstances, the turn to fascism in the U.S.–if and when it occurs–can be effected with less of a rupture in bourgeois legality and therefore will be aided by the hold that bourgeois ideology has over the working class.

At this stage, U.S. fascism does not yet express itself in an all-sided political program which would entail the dismantling of bourgeois democracy. All this means is that the crisis of U.S. capitalism has not yet matured to the point where the bourgeois political system is unable to contain it. For the moment, the growth of fascism in the U.S. is more an ideological than a political process. (The fascist-like activity of the police, frequently cited as the indicator of the rise of fascism, is actually no more than the “normal” operation of the bourgeoisie’s repressive apparatus. To hold otherwise is to encourage illusions about the real nature of bourgeois democracy. From Haymarket to Joe Hill to Sacco and Vanzetti and police assaults on the Black liberation movement in the sixties, the bourgeoisie has never hesitated to use its police power in the most arbitrary and “illegal” fashion while still not abandoning bourgeois democracy as a whole.)

The success of the “new right” in capturing the Republican Party-even though this success has not yet been fully consolidated politically and organizationally–has thus provided U.S. fascism with its most substantial vantage point. It is urgent that this new political and organizational gain of neo-fascism be properly registered by communists. Monopoly capital may not yet be ready to abandon its bourgeois democratic shell and turn to fascism; but it is more aware than ever before that a not unlikely combination of circumstances–the need for armed counter-revolutionary activity somewhere in the world combined with an upsurge in class struggle at home–could mandate a sharp political turn to the right, especially as the bourgeoisie’s traditional option of buying social peace through material concessions increasingly comes up against the hard facts of diminished economic options for capital.

Neo-facism in the U.S. has been engaged in a “moral” crusade for almost a decade now, the essence of which is the ideological preparation for fascism. This crusade has been marked by an upsurge in racism (both the militant and intellectual varieties), sexism, anti-intellectualism, national chauvinism, jingoism, and militarism–in short, all of the main ideological characteristics of fascism.

There can be little doubt that American fascism, like its Nazi predecessor, will rely on a deliberate and conscious attempt to scapegoat racially defined minorities (those of “color”) as the source of society’s ills. Just as the Nazis’ anti-semitism ultimately manifested itself as the projection of an Aryan “superman” and massive genocide against non-Aryan peoples, so U.S. fascism is likewise preparing the way for an exaltation of “white supremacy.”

The elimination of virtually all forms of legal segregation in the sixties has not changed the objective situation of minority peoples; it has merely made more glaring the actual institutionalization of racism in non-legal forms. In fact, the racist counter-offensive has developed precisely in conjunction with the near-complete realization of bourgeois legal equality for minority peoples. The upsurge of the Ku Klux Klan and the noticeable rise in police brutality toward minority peoples represent a resentment at the gains in the legal arena as well as a pointed reminder that racism is protected and reinforced by the police and “private” paramilitary forces.

In the political arena, the racist counter-offensive has surfaced under the banner of “reverse discrimination” and the demogogic appeal to “white rights.” Within this framework, the attacks on social spending (disguised as “tax revolts”), abortion rights, and welfare recipients has had an unmistakable racist content. It is far from coincidence that the neo-fascists have been the leading agitators around these questions. What must be noted with considerable gravity is that in exploiting these issues the fascist right has been able to extend its periphery significantly beyond its own relatively small political base.

Ideologically, we have witnessed a spate of new pseudo-scientific research–in both the biological and sociological fields– which attempts to legitimize racism by breathing new life into long since discredited theories of “racial inferiority.”

Accompanying the neo-fascist, racist upsurge has been a sexist ideological offensive. Just as the slogan “Kuche, Kinder, Kirche” (Kitchen, Children, Church) was advanced by the Nazis as the statement of woman’s appointed domain, so the U.S. fascists have essentially adopted the same outlook in calling for “a return to traditional moral values” largely based on racist and sexist social arrangements.

The opposition to the Equal Rights Amendment–itself a harmless enough constitutional statement which the principal sectors of monopoly capital have no compunctions about endorsing–is thus not based on any illusion that the ERA would actually bring about women’s emancipation. Rather it is, along with the crusade against abortion rights, the reassertion of the legitimacy of traditional modes of authority. Those who see the hand of monopoly capital behind the anti-feminist upsurge miss the point, for under the conditions in which women have become increasingly part of the public labor force, capital does not on principle oppose formal equality between the sexes or the legalization of abortion. The Republican Party, as has been noted by many, had a plank in favor of the ERA in every one of its election platforms for the past 40 years up until this year, and no one would seriously argue that the plank was adopted in defiance of the dictates of monopoly. It was a Nixon-dominated Supreme Court which held anti-abortion statutes to be unconstitutional. (Even the finding that the Hyde amendment forbidding the use of government funds for most abortions was constitutional was managed by the closest of margins, a 5-4 Supreme Court decision.)