First Published: Theoretical Review No. 18, September-October 1980.

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

The socialist left in the United States has developed an extremely limited response to popular culture. Without a general theoretical framework, the dominant view on the left has seen popular culture as primarily a means of manipulation for capitalist ideologues to control the great mass of working people. But while we must acknowledge the fact of manipulation in popular culture, to stop there leaves us unarmed in the process of cultural and ideological class struggle. Such an approach tends to ignore the complexities of popular culture, concentrating on it as mere commodities to be consumed, and not as an aspect of the production and reproduction of daily life.

The notion that reduces popular culture to simply a means of manipulation tends to assume that people work in order to enjoy life through culture and entertainment. But the materialist conception that Marx outlined indicates that under capitalism people must relax and find pleasure in their leisure time in order to prepare their bodies and minds for work. Thus, the possibilities and limitations of cultural entertainment and leisure activity, and their function under capitalism, ultimately “are determined by relations of production.”[1]

This article is an attempt to situate the cultural process, and specifically its expression in rock and roll music, within the realm of the relations of production and reproduction of daily life. As such, it is an attempt to deepen the theoretical discussion of ideology and culture begun in Theoretical Review No. 10 by Paul Costello and Suzanne Rivers in their discussions of movies and cultural criticism.

We will begin by attempting to articulate the complex relationship that exists between culture and ideology. Such a discussion first necessitates generally defining ideology and its function in society. We will then discuss certain tendencies within the general realm of popular culture that have been categorized as youth culture. Within this broad and contradictory category we will explore the development of youth subcultures. This will lay the basis for analyzing the recent developments in popular music that have been categorized as punk rock.

In the process of this discussion we will discuss the form and role of class struggle in ideology, and attempt to define revolutionary cultural practice. We will finally outline the ways in which we feel that elements of punk rock fulfill a revolutionary cultural function.

Although culture clearly has a specific relationship to ideology, Louis Althusser has argued that art and culture are not simply a part of the ideological instance of society. For Althusser, lasting cultural expression “makes us see ... the ideology from which it is born, in which it bathes, from which it detaches itself as art, and to which it alludes.”[2] It is for this reason that we must understand how ideology functions in general, and pervades all human activity, if we are to begin to understand the complex mediation between culture and ideology.

Ideology is the human perception of the ’lived experience’ of human existence itself. This spontaneously perceived ’lived experience’ has a peculiar relationship to the ’real world’. Ideology is simultaneously an allusion to, and an illusion of concrete reality. It is not the real conditions of existence, the ’real world’, that people represent and explain to themselves and others through ideology. What is represented in ideology is their relationship to the experience of their conditions of existence. Put another way, “ideology saturates everyday discourse in the form of common sense . . . .”[3]

The material function of ideology is to reproduce the relationships between people and to their means of producing and reproducing daily life. Today, in class society the dominant ideology tends to develop a broadly defined ideological formation that serves in the last instance to reinforce the existing economic organization of society–to reproduce the existing relations of production as relations of capitalist exploitation. As such, capitalist ideology serves to impose a ’general direction’ on social existence which defines the limits within which people consent to the organization of daily life under capitalism.

Nonetheless, class struggle takes place within the level of ideology. The process of contention between the various classes contains many different elements and trends within their specific ideologies as classes. The ideological class struggle is the process of the strengthening and weakening of different elements within the dominant and various subordinate ideologies. There can be times of seemingly unshakeable dominance by one class, periods of ideological and social calm; as well as periods of uneven disorder, and times of revolutionary upsurge. Each period reflects the strength and weakness of the classes contending for dominance in class society.

The process of the strengthening and weakening of different class forces and ideological elements can be understood as a series of compromises and concessions that the dominant class makes with subordinate classes in order to maintain its political and economic power. We must recognize that the capitalist class remains in power in a generally stable conjuncture more by the consent of the masses than through open political and physical repression. Gramsci called the phenomenon by which the dominant class rules the subordinate classes, the exercising of hegemony. He considered hegemony to be the spontaneous acceptance of the moral and cultural values, as well as the general world outlook and its influence on various practical activities, of the ruling class by the majority of the people of the subordinate classes.

The ideology of the capitalist class is expressed through its intellectuals and the institutions that developed in the capitalists’ struggle to rise to and maintain their dominance, including political parties, churches, schools and the press. These ideological apparatuses are dominated by the structure characterized as the “nation state,” an ideological-political-military fusion of political power. The dominant ideology has the effect of shaping the general consciousness of all women and men living in a given capitalist social formation or “nation state.” It “acts as an agent of social unification, as ’cement’ or a cohesive force which binds together a bloc of diverse classes and strata.”[4]

The hegemony of the ruling class cannot simply be reduced to ideological domination–to securing the consent of the working classes by the imposition of capitalist ideas and values through the process of indoctrination. “On the contrary, a ruling class is more authentically hegemonic the more it leaves to the subordinate classes the possibility of organizing themselves into autonomous forces.”[5] As such these subordinate classes actively consent to the hegemony of the ruling class because it appears that there is no alternative that would permit the full development and fulfillment of themselves as autonomous elements of society.

Nonetheless, Gramsci’s theory of hegemony also contains the possibility of crises of ruling class hegemony. Such crises are the product of the class struggle, which can impact upon the hegemony of the dominant ideology so as to tend toward its dissolution. The working classes can elaborate a new world outlook to challenge the hegemony of the ruling class. The new world outlook can become hegemonic if it succeeds in “welding together” a bloc of diverse classes and class strata, forged by the cohesive force of working class ideology.

The process of the dissolution of ruling class hegemony is a complex unity of ascending and descending forces, which is primarily the result of the contention between the world outlooks of the two major classes. There are times when the old order of things breaks down, and there are preceeding and ensuing, and at times even simultaneous processes of consolidation and reinforcement of the status quo. Working class gains in the area of unemployment insurance in the 1930s, for example, which validated unemployed workers’ right to eat and live, came at the expense of limiting working class struggle to proceed within the realm of reforms– validating the capitalist system and reinforcing the status quo of exploitation. Thus, we should not see the class struggle within ideology as a linear process of additive gains (or losses); but rather as a “war of position/war of movement” (Gramsci) in which the two major classes struggle to exert influence and win allies, moving forward in one area and being pushed back in other areas.

It is for this reason that serious economic crises in advanced capitalist countries do not lead automatically to serious political crises. “The working class will only be able to advance in an economic crisis if it has previously made substantial progress in breaking the hegemony of the ruling class and in building up its own hegemony.”[6] It is with this in mind that we can start to understand the complex relationship between ideology and culture. For, hegemony exists within the realm of culture, and the cultural process affects other social relations in the struggle for hegemony.

As we pointed out earlier, a cultural process has a highly complex relationship to the ideology from which it springs, and to which it alludes. Though culture undeniably rests on an ideological foundation, it cannot be reduced to a simple expression of ideology.

The cultural expression of a group or class is the peculiar and distinctive ’way of life’ of that group or class, “the meanings, values and ideas embodied in institutions, in social relations, in systems of beliefs, in mores and customs, in the uses of objects and material life.”[7] Culture is an important way that the social relations of a class are structured and shaped. But culture is also the manner in which those structures are experienced, understood and interpreted.

Althusser has discussed the potential for provoking modifications in these experiences and interpretations in the process of “great” or lasting cultural expression.

A painter, a writer or a musician proposes new ways of perceiving, of seeing, of hearing, of feeling, etc. ... We can put forward the hypothesis that a great work of art is one which, at the same time that it acts in ideology, separates itself from it by constituting a functioning critique of the ideology which it elaborates, by making an allusion to manners of perceiving, or feeling, or hearing, etc., which, freeing themselves from the latent myths of the existing ideology, transcend it. . . . Art acts in every manner upon the immediate relation with the world, producing a new relation with the world rather than producing knowledge as science does. Therefore, it has a distinct function; although formally, the scheme of the rupture with ideology and the relative independence of the work which results is the same in the case of the ideology-science relation as in the ideology-art relation...[8]

Thus we can say that cultural expression is a relatively autonomous practice of society that has its own internal development, as well as specific relations to the ideological, political and economic levels. As such, cultural expression becomes a material force in the development of society as a whole.

Women and men are formed, and form themselves through culture, social practice and history. Existing cultural patterns represent a sort of “historical reservoir,” a given set of possibilities and limits, which can be taken up, accepted, rejected, transformed or developed. This is the process through which culture is reproduced, transmitted and transcended. In class societies this reproduction, transmission and transcendence take place within the limits imposed, first of all, by class structures and class struggle.

Because the most fundamental groups in society are social classes, the primary cultural configurations are class cultures. Though class cultures are fundamental elements of society; like class ideologies, they are most often mediated by each other and external factors. And, just as the different groups and classes are unequally ranked in relation to each other in class society, so too are class cultures unequally ranked, standing “in opposition to one another, in relations of domination and subordination, along the scale of ’cultural power’.”[9] Thus we can see how the concept of hegemony can be helpful for our understanding of the realm of cultures as well as ideology and politics. Struggles against the dominant culture can seek to modify and resist it, and in some cases even attempt to overthrow its hegemony.

However, subordinate cultures are not always in open conflict with the dominant culture. For long periods subordinate cultures can co-exist with it, negotiating spaces and gaps that develop within it, or making in-roads into the dominant culture. But even when there is a generally stable relationship between dominant and subordinate cultures, struggle still exists. It is just more subtle, and in less open conflict, often resulting in the illusion that the dominant culture has successfully and permanently absorbed subordinate cultures into a homogeneous “national culture.”

Subordinate classes, which find that their culture is penetrated and dominated by the culture of the ruling class, can still find ways of expressing and realizing, in their own specific cultures, perceptions of their position and experiences as a subordinate class. For this reason, though the dominant culture of a complex society represents itself as the culture, it is never a homogeneous structure. It is “layered” and contradictory, reflecting different interests within the dominant class (e.g., monopoly versus competitive capital), and containing different holdovers from the past (e.g., puritanical religious notions in a primarily secular culture); as well as emergent elements of the present and the future, and the elements of other class ideologies it has been forced to absorb in the process of cultural class struggle.

Similar to the complexity of the dominant culture in relation to other class cultures, each class culture is highly complex, containing within it various relatively autonomous “regions” and sub-cultures or countercultures. There are the obvious racial, ethnic and regional variations within a class culture. But there also exist specific cultural relations for youth and the elderly, and particularly for women, who are generally assigned a subordinate role in cultural life dominated primarily by men. These variations relate to the fact that the subordinate groups within the class find meaning and expression in different relations, ideas and objects (or different meanings in the same relations and objects) from the broader class culture.

The concrete distinctiveness of certain sections of the population is a product of specific historically developed subordinate roles assigned and enforced by the dominant ideology and politics. Thus, racial minorities, women and youth are ’structured’ into subordinate roles that place strict limits on their development and means of expression. And though a class culture is composed of broad elements and roles that attempt to embrace the majority of the class, as a class, regardless of sex, race or age, certain differences in cultural expression can lead to the generation of a subculture or a counter-culture.

Relative to class cultures, sub-cultures are sub-sets–smaller, more localized and specific structures within one or the other of the larger cultural realms. Sub-cultures can only exist as a distinct part of a broader class culture, which can be characterized as the “parent culture” (theoretically embracing much more than the divergence between parents and children). What is meant by this is that a sub-culture differs from the “parent culture” in its central concerns and activities, while it also shares certain common elements with the culture from which it derives.

Generally speaking, the tendency is for cohesive subcultures to develop within the subordinate classes, while counter-cultures develop within the dominant culture. Subcultural expressions are one way that oppressed individuals find to cope with the pressures of their subordinate existence, and in negotiating their collective existence. Sub-cultures can be characterized as focusing around certain activities, values and uses of material goods and spaces, which differentiate them in certain significant ways from the broader parent culture.

Four specific modes of expression have been identified as primary elements of sub-cultural style: dress, music, ritual and language (including specific slang, dialect, vocabulary and assigned meanings).[10] Of these four, music can provide a key focal point because it concentrates ideological expression as well as physical and emotional involvement in a fusion that embraces entertainment as well as communication. And though analysis cannot be limited to these areas alone, the high visibility and the increasing fetishization of the specifics of distinctive clothing, talking and playing music; of specific hang-outs, exploits, sports activities and even modes of transportation (low-rider cars in the Southwest, British Mods’ scooters), all tend to clearly identify the differences between sub-cultures and parent class cultures.

Similarly, though distinctly, there is the tendency within the dominant culture towards the generation of alternative counter-cultures, rather than cohesive sub-cultures. The difference here is that while working class sub-cultures tend to develop “clearly articulated, collective structures–often ’near-’ or ’quasi’-gangs” (i.e., Mods and Rockers); it has been observed that “middle-class counter-cultures are diffuse, less group-centered, more individualized. The latter precipitate, typically, not tight sub-cultures but a diffuse counter-culture milieu.”[11]

The primary reason that counter-cultural alternative institutions can develop within, and even in conscious ideological and political opposition to, the dominant culture is that that culture affords the space and opportunity (economically and ideologically) for sections of it to drop out of circulation and to explore alternatives. Such exploration can take the form of new patterns of living and family life, as well as experimenting with careers that fuse leisure and work experiences (the retreat to the country commune, the artisan production of arts and crafts, etc.). The working class is generally afforded no such options. Their life is persistently and consistently structured by the “dominating alternative rhythms” (Clarke) of weekend relaxation and the back-to-work, “Stormy Monday” blues.

The distinction between sub-cultures and countercultures is important for an analysis of punk rock because, while punk rock in England developed as part of a working class sub-culture, it has always functioned in the U.S. as a counter-culture. But the specific position of youth within the subordinate and dominant classes tends to generate specifically similar responses to the predominant rhythmic patterns of daily life such that a concept of youth culture is a useful analytical tool. This is the case primarily because even though there are distinctly different responses, there are definite similarities (at times more so than at other times) between both youth sub-cultural and counter-cultural experiences.

There have been numerous theories and interpretations of youth culture in general. Liberals and conservatives have tended to generate their own meanings and responses; and Marxists have disagreed not only on definitions, but also on the validity of the concept itself. One of the most successful contributions to a Marxist understanding of youth culture was made by Martin Jacques, a prominent British communist cultural critic, in 1973 in his article “Trends in Youth Culture.” Jacques outlined his premise for utilizing the concept of youth culture as follows:

The correctness of the insistence on the distinctness of each new generation seems ... to lie in the fact that each generation matures in a new set of political, economic, social and ideological conditions. They thus share in some degree or other various common experiences and therefore expectations and values which are different from those of other generations. The degree to which this is true . . . depends on the extent and manner in which these new circumstances are different from the ones experienced by the older generations.[12]

But Jacques is careful not to liquidate the concrete differences between the experiences of the youth of various social classes. In much the same way that we discussed subcultures in general above, he explains that,

Firstly, within each class or fraction of the class, the youth element possesses particular and distinctive characteristics in relation to the class as a whole and, secondly, youth in general shares certain similar overall characteristics. . . . But it must be said that youth culture is not a monolithic whole, rather it is more appropriate in many ways to speak of youth cultures.[13]

Jacques argues that the disparity that has distinguished the experiences of the post-war generations (those born during or after 1945) from previous generations has been most dramatic in three areas: (1) the ideological arena, (2) the numerical and material position of youth, and (3) its social composition. This disparity reflects the fundamental differences between the long wave of capitalist contraction and crisis which characterized the period between the world wars, and the long wave of capitalist expansion following the second world war.

Ideologically, the post-war generations have never confronted the major problems that dominated the lives of the previous generations, namely massive unemployment and fascism in power in major industrial countries. Because youth have come to accept a state of relatively full employment and rising living standards as normal, they have judged capitalist society by quite different standards than those most likely utilized by people who lived through the 1930s.

Second, the post-war “baby-booms” produced large increases in the population between the ages of 15 and 25 by 1970, which are only now beginning to decline. This combined with the growth in the educational sphere, including the emphasis on extending the years spent in education, the increased income and spending capacity of working youth, and the declining role of the family, have all served to increase the ideological, economic and political autonomy and influence of youth as expressed in such phenomenon as popular music, clothing and sexual behavior.

Concerning the social composition of youth, the growing importance of various strata, of technical, scientific, intellectual and service related labor within the realm of wage-labor, especially in food production, entertainment and health care, as well as the financial and distribution sectors of the economy, has had a marked effect on working class youth. This can be seen in the increasingly diverse areas and types of employment, with very different traditions, work situations, degrees of organization and educational requirements. Further, the length of time spent in education, including high school, community colleges and technical schools, as well as universities, has meant that more youth not only receive more education, but also remain outside of the full-time labor market for longer periods of time, quite often not by choice.

Thus, the composition of working class youth is now much more diverse than ever before, and numerically certain new sections are becoming quite important. Also, since most students enter the ranks of the wage-labor force, the social distance between student youth and working class youth, and between sub-cultural and counter-cultural responses, can at times become considerably narrowed.

Though these facts should not be exaggerated in considering the existence of a youth culture, especially given the potential for extreme divergence of the experience of a young factory worker in Oakland and a secretary on Wall Street, and the wide divergence of national minority cultures, the tendencies do exist and the implications are important. “In particular, there is a growing cross-fertilization of ideas and modes of behavior between the different strata of youth.”[14]

The general oppression of working youth can be summarized into four major categories. (1) Increased economic exploitation: Most often youth receive much lower wages for doing the same amount of work as their elders. (2) A narrowly defined, and even stifling educational process: While education has helped raise the general level of knowledge and culture, through its very organization and character it has tended to limit the cultural and intellectual development of youth. This is especially the case with the process of “tracking” and through the process of generally defining students as passive receivers of information. (3) The contradictory character of the family: The family not only can sustain and provide support for youth, but is also one of the most important areas for conditioning and socializing children and youth into the acceptance of the established values of society. This process can often involve the older generation teaching old and regressive values, such as racism and sexism, and negative practices such as alcoholism and child abuse. (4) Finally, the greater significance of the cultural industry, due to the growth in leisure activity/expenditure of youth, has had two fundamental characteristics: the tendency to turn anything marketable into a commodity, which treats youth more and more as only a market of consumers; and the further tendency to turn the individual into a passive “receiver.”

The rebellion of youth against these various aspects of their existence takes on different forms depending on the class character of those responding. Music has tended to become a powerful vehicle for this rebellion because it can provide an expression for the focal concerns of youth, in words as well as sounds. But given the hegemony of capitalist ideology, the rebellion tends toward individualism and subjectivism, particularly in a counter-cultural framework, such as prevailed in the U.S. in the 1960s. This can develop further into a more consciously political response of Utopian anarchism that rejects all authority and organization. Nonetheless, “the degree to which cultural tendencies are progressive cannot be judged solely in terms of their content (e.g., how revolutionary are the words of a song?), but must also take into account their form, that is, the extent to which they imply an emphasis on participation, on the active involvement of the individual/audience in new ways and at different levels.”[15] Thus we can see a need to develop a well articulated theory of what in fact constitutes revolutionary cultural practice.

To define revolutionary cultural practice we need to return to certain elements of our discussion of ideological class struggle, as well as to develop certain new elements specific to cultural practice itself.

If we accept Althusser’s definition of cultural production as an act within ideology that can separate itself from that ideology through a critique of certain myths inherent in that ideology, we can see that transcending the immediate relations is possible through cultural expression. New relations can be produced in culture. The question of whether or not such new relations are revolutionary can only be judged in their relation to, and impact on the broader realm of ideological class struggle.

Does the portrayal and possible transcendence of existing relations serve to reinforce the hegemony of the dominant class ideologically and politically, or does it serve tendencies toward the dissolution of that hegemony? A song, or poster, or work of art can be said to be revolutionary if it serves to help break down the hegemony of the ruling class. Further, a single cultural object can contain both tendencies. Our analysis must decipher which tendency is dominant, not only when it is created, but also when it is appreciated by an audience and/or coopted by capital.

Fundamental to this understanding of class struggle in culture and ideology is a conception of revolution painfully absent in the theories and strategies of the majority of revolutionary groups in the USA today. Most revolutionaries have a vision of revolution that involves the dramatic physical assault by the working class against the capitalist state, in much the same way that the Russian working class rose to power in 1917.

However, such an approach was successful for the Russians because of the concentration of state power in a narrowly defined power base. The autocratic regime had been overthrown by the mobilization of the vast majority of the popular masses against the Czar. Bourgeois rule after February, 1917, was tentative, and based on the support or neutrality of the working class and its primary ally, the peasantry. When this support was withdrawn, the state was highly vulnerable and susceptible to a frontal assault.

In advanced capitalist countries, capitalist hegemony and power is centered in a vast state apparatus that includes the courts, education and “democratic” institutions, as well as the military and police, that all combine with the other ideological apparatuses to reproduce capitalist ideological and political hegemony on a broad and pervasive scale. Thus a frontal assault on an advanced capitalist state by itself, without other forms of struggle is no longer a viable strategy. It is for this reason that Gramsci saw the need to develop the conception of the “war of position/war of movement” against capitalist hegemony.

It is precisely this struggle for working class hegemony and its necessary class alliances that points out the validity of a conception that sees revolutionary cultural practice in whatever elements that serve to break down capitalist hegemony. The need for a process of developing working class hegemony can not be envisioned in isolation from the broad struggle against the hegemony of the ruling class, which also maintains alliances and unites other classes and class strata. Further, such a developmental process requires a large and effective revolutionary party actively practicing the science of Marxism-Leninism in the service of the working class.

Our understanding here is based on the fact that a revolutionary situation is not simply an opposition of the working class to the capitalists. A revolutionary situation is rather a complex accumulation of many social contradictions acting simultaneously with the fundamental class contradiction. This is the Leninist conception of revolution, and Althusser has provided us with a theoretical summation of this process.

If this [class] contradiction is to become ’active’ in the strongest sense, to become a ruptural principle, there must be an accumulation of ’circumstances’ and ’currents’ so that whatever their origin and sense (and many of them will necessarily be paradoxically foreign to the revolution in origin and sense, or even its ’direct opponents’), they ’fuse’ into a ruptural unity: when they produce the result of the immense majority of the popular masses grouped in an assault on a regime which its ruling classes are unable to defend.[16] [Althusser’s italics]

Thus, any elements that serve to challenge the authority and legitimacy of the status quo can serve a revolutionary function.

This is not to say that they will do so consciously, or that they will support the revolutionary process itself. It is to simply acknowledge the objective effect that such elements can have in challenging the hegemony of the ruling class. It is the role of communists to provide direction for such challenges, and to struggle to develop an alternative to capitalist hegemony in the ideology of the working class. And we must be quite clear on the fundamental distinction between revolutionary communist practice and revolutionary anti-capitalist practice, both of which are vital to successful socialist revolution.

Once communists understand the class struggle that is unfolding we can undertake conscious ideological campaigns to influence audiences, as well as certain musicians. Energy must be concentrated on reaching the audience because the masses are much more stable than a few isolated individual musicians, and it is the masses who will create their own artists and musicians, both by organically producing them and by supporting those who reflect their ideals. Then the cultural workers can be involved in the process of learning the needs and desires of the working masses, and acting for their fulfillment, i.e., developing working class hegemony in the cultural sphere.

The cultural process must, therefore, be understood as highly contradictory, and potentially highly volatile. It is no accident that the dominant culture is overwhelmingly filled with elements that serve to avoid and obscure the concrete class contradictions, as well as any contradictions or history that serve to call into question the existing relations of existence. The dominant culture under capitalism constantly strives to convince people that the way things are is part of a “natural” progression, and that most contradictions are the same age old questions that have maintained the same “essence” over the years, even if such myths fly in the face of concrete and historical reality.

One of the more all pervasive myths today is that of consumerism, a myth that actually has quite recent origins in opposition to the traditionally frugal work ethic.

Publicity is the culture of the consumer society. It propagates through images that society’s belief in itself. –John Berger, Ways of Seeing

I know I’m artificial But don’t put the blame on me. I was reared with appliances In a consumer society. –Poly Styrene, “Art-I-Ficial”

Under advanced capitalism the dominant tendency is for people to seek out relaxation and respite from the pressures and demands of work in the consumption of commodities. This is due tcr the ideological pressures to conform to the needs of capital in meeting one’s needs for physical and emotional pleasure. Not only does the advertising/media industry penetrate our consciousness to distinguish between products, but advertising also functions to validate the relations of commodity consumption themselves. As John Berger, a British Marxist novelist and critic, puts it so well in Ways of Seeing,

The purpose of publicity is to make the spectator marginally dissatisfied with his present way of life. Not with the way of life of society, but with his own within it. It suggests that if he buys what it is offering, his life will become better. It offers him an improved alternative to what he is.[17]

The basic needs for relaxation can be met through various means, including escape into fantasy, isolated individual consumption of objects and food or drugs, active participation in sports, passive entertainment by most movies, television, music concerts and drama; or on another level, intellectual expansion and critical interaction. Materially, the need to regenerate ones ability to work, through the process of relaxation, is mystified and channeled by the ideological mechanisms of the media and advertising into the avenue of consumerism. Further,

Publicity turns consumption into a substitute for democracy. The choice of what one eats (or wears or drives) takes the place of significant political choice. Publicity helps to mask and compensate for all that is undemocratic within society. . . [18]

Thus we can see that within the realm of consumer society the dominant tendency is toward manipulation, on both conscious and subliminal levels. But there is also a subordinate tendency of the consumer to have a degree of control over what is manufactured. This degree of control exists in the fact that individuals can choose what they will buy (a record or a blank tape, or a book, for instance), and even if they will make a purchase at all (listening to, or taping a friend’s record, or using the library). Under capitalism the process of any choice is predicated on the amount of surplus income available to purchase cultural commodities, which is directly connected to the standard of living of the masses, and to the rate of inflation.

And though we must not overemphasize the ability of a consumer to make an unmediated choice, this process does involve elements of an active role that the masses have in shaping the mass cultural media, whereby they become “responsible for a social demand for a new kind of artistic activity.”[19] This active role is one reason that the product boycott can be an effective weapon of struggle.

This complex relationship between consumer and commodity mediates the link in popular culture between the artist, musician or actor, and the values and feelings of the masses, toward themselves, the artist, the cultural object and toward society as a whole. The dialectical interaction that takes place is such that the cultural product is not only shaped and enjoyed by the masses, but also shapes and influences them in diverse ways. For this reason any analysis of the cultural process must address the response of the audience.

Because the aim of cultural and media products is to fulfill sensorial and emotional enjoyment, the response of the viewer or listener becomes crucial. The most prevalent avenue for a respite from, and in preparation for work is the realm of “leisure effects.” Leisure effects generate a passive “receiver” response, where the individual seeks to be entertained rather than to be actively involved. A song or movie can serve to generate leisure effects by creating an avenue for escape into apathy and fantasy. But a song or movie can also have another effect; it can serve to orient the viewer/ listener to a “critical response ... in the sense that he or she will be provoked into thinking and questioning by it.”[20] One way that such critical orientation can be affected is through the shock effect of jolting the audience out of the more passive habitual response.

Walter Benjamin, the German Marxist literary critic who first developed an understanding of shock effects in culture, reflected on the fulfillment of a more general human need through the process of shock effects. “Man’s need to expose himself to shock effects is his adjustment to the dangers threatening him.”[21] And to a large extent the shock effect has been absorbed into the evening news. The daily shock of the brutality of modern society–from the chemical destruction of the Love Canal to police violence in Miami, has become for the most part an accepted part of our everyday lives. For this reason, to be productive in a progressive sense the shock effect must contain a cognitive aspect; it “should be cushioned by heightened presence of mind” (Benjamin), as well as possess the “tactile” effect of a jolt out of the contemplative evasion of social pressures.

This process of shock effects is crucial for our understanding of the phenomenon of punk rock; for, the unity of this cultural phenomenon has been described as issuing from its “external relation to pre-existing popular music, and in the shock tactics with which its exponents went about their work.”[22] But before we present a fuller analysis of punk rock, it is necessary for us to briefly outline the “pre-existing popular music” to which punk became such a dramatic external reaction.

Since popular music is a relatively autonomous element within the complex totality of society, a direct and unmediated connection between the state of the economy and developments in music cannot be mechanically imposed on our analysis. However, whenever possible we must take into account the effects of an expanding or contracting economy, and the economy of the music industry itself, on the cultural expression of a given period, as well as the effects of other broad social factors such as war and repression. Concrete examples of this include anti-war lyrics in the music of a wide range of mainstream rock and roll bands during the Vietnam war, and the angry response of British punk rockers to the prospect of dead-end jobs and welfare lines, given the current economic situation in England.

Because of its relative autonomy as a cultural phenomenon, rock and roll music has its own internal rhythm of development which leads to periods of vitality and creativity, as well as periods of redundant repetition and stagnation. This rhythm of development is more or less independent of other societal and cultural developments depending on a complex interaction of all the elements involved.

The original fusion of popular rhythm and blues, country music and rockabilly–all musical expressions that sprang from the culture of working people–has become a wide-ranging musical realm that embraces on the one hand a soft and mellow, folk music sound, and on the other a driving energetic sound that is at times harsh and abrasive. On the one hand rock and roll includes a plethora of lyrical pablum, and on the other intelligent social critique. The pioneering musical work of Chuck Berry and Elvis Presley at times is all but lost in the maze-like intricacies of musical production that rely quite often on a strict division of labor between technically proficient studio session artists backing media created stars with questionable musical talents.

Various factors combined such that the 1960s can generally be characterized as a creative period for rock and roll. Basically a wide range of new elements were being incorporated into the established parameters of popular music. Between 1964 and 1967 rock and roll continued to occupy the center of youth culture, and helped to generate an unusual homogeneity between both student youth and working class youth, with many of the young musicians coming from working class backgrounds.

The music displayed a remarkable capacity for musical and artistic growth by exploring such diverse musical forms as blues, soul, folk, jazz and even classical music. Simultaneously a tendency developed where some lyricists moved beyond the traditional obsessive preoccupation of popular music with “love” and its achievement and demise.

Bob Dylan was a key influence in exploring a wider range of lyrical content, and his songs condemning the war and hypocrisy in general, and even aspects of capitalist exploitation, helped the music begin to “articulate the evolving mood of youth not only through rhythm, intensity of sound, melody and instrumentation, but also through words.”[23] The ideological developments of this period eventually generated an overall move toward the “counterculture” that called for the building of a Utopian alternative society through dropping out and “doing your own thing,” which was eventually reflected in the songs and lifestyles of many youth and musicians, and in part led to the cultural complacency of the early 1970s.

If the 1960s can be seen as a period of creativity for rock and roll music, the early 1970s was generally a period of regression and decline. It was a period when many artists reached star status and found that their distinctive style could economically serve them well with repetitions of worn out copies of previous innovations. The music also reflected the fact that most student activists of the 1960s had entered the realm of gainful employment and were feeling far less rebellious. The brutality of the Kent and Jackson State massacres most assuredly added to the mood of apathy and passive acceptance of the status quo. But there was also the reality of certain successful struggles to liberalize sexual and drug taboos, if not actual laws, which led quite often to self-indulgence rather than a realization that there were broader political issues involved.

It was not until 1976 that a new period in rock and roll–a new wave of innovation–could be seen solidly emerging. Younger British and American musicians, bored with the pat styles of previous successes and locked out of the star dominated recording industry, explored new, and often exciting techniques, while reinvestigating the origins of rock and roll music.

At the same time that rock and roll was in decline in the early 1970s, the particularities of Jamaican culture, religion and politics were generating a new and vital expression of Jamaican “lower class” popular music–reggae.[24] Many young white musicians of Britain, exposed to reggae by West Indian immigrants, began to experiment with a new direction for musical expression. Reggae music became an influence on popular rock and roll after Jimmy Cliff starred in “The Harder They Come,” and such influence became wide-spread after Eric Clapton covered (performed) Bob Marley’s “I Shot the Sheriff.” New wave musicians have especially relied on reggae rhythms and beat (with varying degrees of success). Further, some musicians like the punk rockers and Elvis Costello, not only incorporated elements of reggae rhythms, but also accepted reggae’s emphasis on social criticism as a lyrical style; content conspicuously absent from most recent rock and roll.

The social ferment generated by declining economic opportunities in Britain found expression in the new wave of social protest in rock and roll music. But where previous protests against the system tended toward pacifism and “peace and love,” the lack of opportunities or alternatives to the prevailing economic conditions gave rise to a much angrier cry of protest, more aggressive and even at times more violent. Specifically, the most important musical developments in England developed as a working class sub-cultural response to the conditions of existence of sections of the working and unemployed youth centered around the musical expression of punk rock.

In the USA, parallel musical developments sprang more from the earlier indigenous innovations of the Velvet Underground, the MC5, Iggy and the Stooges, and Frank Zappa, than an imported element like reggae. But while musicians as diverse as the Ramones, Patti Smith, the Talking Heads, Blondie and DEVO were developing in a US new wave, and gained increasing national exposure in 1977, it was developments in British music that stimulated a real surge in musical and media activity.

The crucial difference between the new British and American rock and roll centers around the fact that at the core of the British new wave was the militant working class sub-cultural phenomenon of punk rock. This is especially important in the subject matter taken up, and also in the politics and targets of critique. Specifically, punk rock expression validated, and in fact forcibly injected, an extremely broad realm of social issues and questions as “acceptable” content in popular music: political questions about dead-end jobs, identity and militarism. The American new wave was not centered around punk rock; and US punk itself grew more out of the dominant culture as a counterculture without real working class affinities.

But though British punk was a dynamic stimulus for British new wave, it was more the aggression and energy that tended to revitalize and challenge other musicians to explore new areas, rather than punk politics. The new wave of rock and roll encompasses an extremely diverse range of musical styles and approaches and political attitudes. As a category it most accurately describes the new field of young musicians open to experimentation and different musical forms such as reggae and other West Indian sounds (steel drums), as opposed to the more “conservative” established rock and roll stars.

New wave as a shift toward younger musicians, however, does not avoid the old contradictions of rock and roll and popular culture in general. There is still a tendency toward male dominated bands, with notable exceptions like Blondie, the Pretenders and the Patti Smith Group; there is virtually no cross-over of acceptance of US Black and Latin musicians; and many of the performers put aside their more rebellious attitudes toward the system once they are assured of a major recording contract. Sex, love and sexism have not disappeared as dominant themes; they have just tended to take slightly different, and quite often more aggressive forms. (The most notable US exception to this is the Talking Heads.)

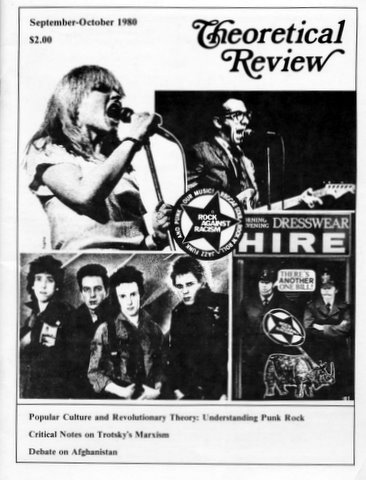

But though the new wave has reproduced many traditional contradictions, some important radical and progressive elements have emerged that deserve closer attention from the left. Of special importance are certain tendencies to critique the dominant ideologies of British royalty, religion, militarism and fascism, and even aspects of the popular music industry itself. These tendencies are especially clear in punk rock, and in the broad cultural-political unity that has been achieved in Rock Against Racism, which will be discussed below.

However, the progressive aspects of new wave cannot be reduced to a part of the British punk scene. This is especially true in light of the emerging dynamism of strong and assertive women in rock and roll, and the increasing acceptance of new wave groups that challenge the listener to think and question existing social relations.[25] But the special circumstances in Britain of a highly charged political and economic environment have generated a musical phenomenon with elements of broad political significance. This is especially true because the economic and political crises are coupled with the British sub-cultural tradition of aggressive activism on the part of affinity groups of young people in defense of their musical preferences. This aggressive defense can be seen in the common attitude among British punks which was vividly expressed in music by Tom Robinson, a gay activist in Rock Against Racism, when he declared, “We ain’t gonna take it; NO MORE!”[26]

Punk rock got its name from John Sinclair, who coined the phrase in describing the aggressive militance and White Panther politics of the MC5. But for years there was no broad musical phenomenon to accompany the name. In the United States the Ramones, with their high energy, punk parodies of love, drugs and mental “health” institutions, were the main purveyors of punk energy for several years, until their stance was paralleled by such British groups as the Clash and the Sex Pistols.

In Britain punk rock owes as much to the rhythm and social protest of reggae, as it does to the aggressive energy of the MC5 and the Ramones. And it was British punk that began to generate the most media attention. The outrageous antics of the Sex Pistols, and their flagrant disrespect for, and bitter critique of the venerable Queen and her Royal institutions and gala Jubilee, were a media goldmine. The publicity transformed “punk rock” into a household word, and generated intense interest in this new “political” rock and roll.

Musically, punk is solidly a part of the new wave movement to return to rock and roll basics. High energy rock and roll, played fast, loud and hard, punk rock also emphasizes brevity, in contrast to the extended free-form solos and jams of the established rock musicians who have attempted to engender rock as “art for art’s sake,” with convoluted excursions into “rock and roll fantasy” (The Kinks).

The Rock revival of the 1960s, and its “revolutionary” spirit of the youth culture as an expression of collective pride, fun, self-confidence and good humor, tapped an entirely different mood than punk, which has tended to be an expression of boredom, doubt, anger, and even self-disgust.

Today’s teenage frustration is caused, not by fuddy-duddy parents, not by easily shocked adults, but by an intractable economic situation, by a society in which everyone talks a lot about the plight of the youth but no one does anything. This isn’t an ideology, it is a mood.[27]

And this mood has been expressed in both progressive and regressive ways.

Punk rock shares many elements with new wave in general, the most telling is its highly contradictory character and extreme levels of uneven development. Unfortunately, the punk rockers of the USA, again more of a counter-cultural than a working class sub-cultural phenomenon, have tended to reflect many of the regressive elements of the US dominant culture, including mindlessness and aggressive sexism. Because of the broad range of attitudes toward politics, life and women, as we mentioned before, the primary element that unifies all punk rock, regardless of its subject matter and the intent of the musicians, is the use of shock tactics.

Thus, an important aspect of deciphering the significance of punk rock as a whole, and particularly the significance of progressive punks like the Clash, X-Ray Spexs, Sham 69 and Stiff Little Fingers, is to recognize that they tend to generate “a heightened presence of mind” (Benjamin) to accompany their shock tactics. Progressive punks tend to orient the listener toward progressive social goals, or offer clear critiques of regressive elements of society. The clearest example of such an orientation is the developments around Rock Against Racism (discussed below).

Interestingly enough, a debate has existed within a group of rock and roll critics over more than the value and content of punk as a musical form. Debate has also centered on the actual existence of punk as a continuing cultural movement capable of influencing popular music in general. According to some critics the punk movement was dead in late 1977, “fractured along the lines of its own internal contradictions” (Laing). But what is most important at this time, years after a cohesive “movement” has faded, is that the demise of punk marked the beginning, rather than the end of a phase of ideological struggle within popular music itself.

The contradictory character of this beginning is nowhere more evident than in the United States. Here new wave, which was born in the English working class sub-culture has developed as an element of a counter-culture, which, by definition, is lacking strong working class roots. As such new wave in the United States takes on many of the features of the counter-cultural experience as it presently exists, de-politicized, individualistic, heavily influenced by sexism and racist values.

Even English political punk rock, when introduced in this country, has difficulty making the appropriate connections with its new found American audience, because of their different ideological and cultural perceptions. Some groups are sensitive to the dilution of the political significance of their lyrics which results from this trans-Atlantic voyage. On his first album Elvis Costello included a song against the fascist revival in England, aimed at Oswald Mosley (“Mr. Oswald”), its acknowledged leader in the 1930s. On his North American tour, however, Costello found the political impact of his song diminished by the audience’s unfamiliarity with English politics. He thereupon rewrote the song especially for the tour with new political lyrics, this time about the Kennedy assassination and Lee Harvey Oswald.

In some ways punk was transcended and its musicians absorbed, however tentatively, into the broad spectrum of popular rock and roll. The ultimate example of this is the widespread popular acceptance of the Clash, once called “the punk’s punks.” But since punk continues to exist, admittedly in a scattered rather than a concentrated form, it opened many doors and still generates a pressure on popular music to maintain less rigidly defined boundaries, open to new musicians who have something to say.

But our analysis of punk rock must address more than what the musicians have to say. To successfully analyze a cultural phenomenon in such a way as to productively intervene as communists in the class struggle in popular culture, we must address four major elements in a cultural exchange. These elements are the musician or cultural worker, the song or work itself, the audience, and the role of the capitalist cultural and media industries. In each concrete situation, at any particular moment in time, there will be uneven development of various aspects of each of these elements. Each must be understood separately and in their dialectical interconnection.

The elements of a cultural exchange within popular culture exist as a complex totality with various internal contradictions. At any given time, specific internal contradictions will be dominant, and in each instance the interaction of the dominant aspects of the four elements will combine with the secondary aspects to generate a cultural object of varying degrees of importance to the individuals involved, and to society as a whole. A clear example of the wide divergence of historical development, just within the category of the artist, can be seen in Bob Dylan’s political/ philosophical role in culture and society during the Vietnam war, and his current religious/cultural significance today.

With these thoughts in mind we can begin to deepen our understanding of punk rock through a discussion of punk rock musicians.

I don’t want to know about what the rich are doing, I don’t want to go where the rich are going. “Garageland”–Joe Strummer and Mick Jones of the Clash

The intention of a musician, artist, or film producer is an important aspect of the process of cultural production, though by itself such intent does not determine the full character of a cultural product, as we shall soon see.

Some people have more dedication to, and/or access to the necessary materials, instruments and time for creative production, and express their inner visions and feelings in ways that can find acceptance by others. This means that the creative intent of an individual can take on more significance than an individual response to one’s environment and life, and become a social expression as well. But though a certain commonality of our lived environment can be expressed for the social whole through an individual, this is not to say that a collective expression is not possible or not necessary. The individual expression is simply the most common under modern capitalism, where the dominant ideology, and most relations of production reinforce and perpetuate individualism.

In responding to the environment and the history of their cultural expression, individuals can accept or reject their experiences. The most frequent response embodies a complex interaction of both acceptance and rejection, with one degree or another of transformation of historical expression. Within this framework the intent of a musician, author or artist can be both progressive and/or backward, and still give expression to broader social attitudes and desires.

Further, the critical tools of satire and parody are means of expressing social criticism that can be both effective and highly contradictory. These forms of expression create a complex link between the intent of the artist and the response of the audience in the process of the creation and perception of a cultural object. We will address this complex link more when we discuss the response of punk audiences. But first we will address the expressed intent of punk musicians.

Punks have become (in)famous for their open hostility to the musical status quo:

That hostility took three major forms: a challenge to the ’capital-intensive’ production of music within the orbit of the multi-nationals, a rejection of the ideology of ’artistic excellence’ which was influential among established musicians, and the aggressive injection of new subject-matter into popular song, much of which (including politics) had previously been taboo.[28]

The established musicians were technically proficient in the use of their instruments and the sophisticated recording equipment increasingly popular with producers looking for a “polished” sound. Thus they were offered the vast majority of recording contracts. In the attempt to justify their own drift away from the raw energy and youthful exuberance of early rock and roll, toward the polished and “sophisticated” styles of rock and roll as “high art” so highly prized by most record companies, many rock stars produced ghastly hybrids of pretentious lyrics, that were often willfully obscure, combined with worn out repetitive sounds. Such attempts to justify ensconement as guitar virtuosos and operatic geniuses was more of an expression of elitism and condescension toward the “faceless crowd,” than it was an attempt to gain recognition for their acknowledged abilities. (The ultimate parody of this elitism is Joe Jackson’s claim that his fans can never hope to touch or see him; they can “only hope to hear me on your Radio.” 10CC has addressed the “high art” debate in “Art for Art’s sake,” where they expose the ultimate concern of most established musicians as “money, for God’s sake!”)

With most record labels trying to make their profits by pushing the established, well-known artists, the slump in the record industry signaled less money available to take a chance on new and un-proven talent. Thus, it became impossible for new groups to get a chance to record songs through normal channels and be heard by more than their local fans. This meant quite simply that these new groups could not make a living making music. Out of the frustration that these circumstances created came the ideology of the “garage bands.” Jimmy Pursey of Sham 69 explained it this way:

. . . What punk did was give a lot of little groups all over the country the start Tiny little groups just getting up on the stage playing . . . singing about the environments about them. ’Cos they didn’t have to copy anymore. Like previously all bands played old Beatles tunes and that. Now they just got up and did it.[29]

Another aspect of the attitudes of punk musicians in stark contrast to the star system was/is an openness for interaction between musicians and the audience. When asked by Melody Maker in March of this year why Stiff Little Fingers, an Irish band from Ulster, still considered themselves a punk band, Jake Burns replied,

We are still true to the initial values; we still believe in it as an extension of the audience. We will, hopefully, always be willing to play gigs to those kids and then afterwards hang out ... to see whoever wants to come backstage. We’ve always talked to the kids because... knowing what sort of people are filling those seats is more important [than knowing how many people attended].[30]

Further, the punk’s attitude that anyone can play music for entertainment has been born out, as the best and most dedicated of the punks have shown that they can learn to play well in the process of trying, and most often succeeding, to entertain an audience.

Control over the means of production is one of the key issues that punks have addressed, not only in their songs, but also in contract negotiations. Most of the militant progressive punks have songs denouncing their treatment by the multinational record companies. The importance of the early struggles of the Sex Pistols and the Clash in attempting to maintain control over their music and contracts is reflected in the fact that other bands can now take a firmer stand with the corporations. The Gang of Four, an avowedly socialist British band, recently negotiated a contract with Warner Brother for the release of their album Entertainment! that gave the band nearly complete control over their music, advertising and the album cover, all areas where most musicians find they must capitulate to monopoly manipulation. Further, the Clash reportedly demanded that the price of their double album London Calling (CBS) be kept low enough so their fans could afford to buy it.

Many new wave and punk musicians go further in their critique of corporate manipulation, pin-pointing the role of the media, and radio explicitly, in shaping people’s consciousness. The most articulate critique is Elvis Costello’s “Radio, Radio,” where he explains how the radio industry presents itself as the “voice of reason,” advising us what to do and acting to “anesthetize the way that you feel.” Costello worries about “the times ahead,” and denounces those who sit around “overwhelmed by indifference,” unable to look beyond their radios and tape recorders.

As we mentioned before, many British punk musicians are consciously aware of the extreme contradictions existing in modern society, and have built their musical expression around the angry protest of a segment of the youth population. The Clash sing about career opportunities that “never knock,” and recognize that “All the power is in the hands/of people rich enough to buy it.” In 1977 the only solution for the Clash seemed to be a “White Riot,” where white people who had had enough of economic difficulties, were challenged to take the lead from Black people who weren’t afraid to “throw a brick.”

Needless to say, anarchistic themes abound in punk rock, as do nihilistic themes, particularly in the US. The Deadboys (US punks) ironically sang about how much “fun” it is to be down and out and know “you’re gonna die young.” And of course there is always Richard Hell and the Voidoids’ “Blank Generation.” But anarchism and nihilism were not the only reactions to existing reality taken up by punks. The English group Chelsea has a popular single where they sing “We’ve got a right to work,” which was one of the British Socialist Workers Party’s (SWP) agitational slogans.

Directly connected to the protest against dead-end jobs and unemployment is an anti-military stance that threads through much of punk rock, and even some new wave in general. This is so because a commonly advised “alternative” to unemployment is military service. In “Oliver’s Army” Elvis Costello ironically proposes the deployment of the British colonial army around the world: on the “murder mile” in Ireland, to Palestine and to Johannesburg, as a solution to those who are “out of luck or out of work.” And the Clash make it clear that joining the army or the RAF (Royal Air Force) are career opportunities that they can do without.

On their first album the Clash also denounced “Hate and War.” They further develop progressive themes on London Calling. In “Working for the Clampdown” those who are angry at the cruelty of Margaret Thatcher’s racist clampdown on “undesirables” are encouraged to turn that anger into power. In “Spanish Bombs” the Clash draw explicit parallels between the struggles in Ireland and in the Basque territory and the Spanish Civil War. But not only is “Spanish Bombs” a reflection on the brutalities of civil war, it also keeps alive the aspirations of those who fought and died in the trenches with the remembrance that “The hillsides ring with ’Free the people’.”

The Irish band Stiff Little Fingers expresses an angry impatience with the brutality of the British occupation of their native land on Inflammable Material. Like so many youthful musicians, playing in a rock band is an attempt to escape the stagnation of life in Ireland where so many young people end up living and working next door to their parents in a resigned acceptance of the constant state of civil war. On Inflammable Material (Rough Trade) they graphically reflected the Irish situation in harsh and abrasive guitar work and raspy, shouted vocal delivery, interestingly combined at times with Beach Boys harmonies and the beat and rhythm of reggae. Presenting an anarchistic pacifism in “Wasted Life,” on “Alternative Ulster” the band calls for an “anti-security force.” SLF’s dominant message is to “stop the killing,” especially clearly presented in their mournful cover of Bob Marley’s “Johnny Was.” Finally, it would be hard to find a clearer indictment of the false promises of army recruiters than “Tin Soldier,” on SLF’s second album. Nobody’s Heroes (Chrysalis) develops the theme of challenging listeners to look for strength in themselves, blacks and whites, and not to expect rock stars to solve social problems.

One of the most biting anti-military songs to come out of the British new wave is the Gang of Four’s “Armalite Rifle.” This song draws a clear connection between the presence of British troops in Ireland and the pervasive anti-Irish ideology of the British ruling class. The armalite rifle functions “like Irish jokes on the BBC,” to maintain and reproduce the oppression of Ireland. A more in depth discussion of the Gang of Four is developed below.

Take me and strap me to the electric chair. But you’ll never kill me I’ll always be there. The Deadboys–“Son of Sam”

In spite of the punks who develop progressive themes, expression of sexism, racism and mindless violence are common themes for a number of punk bands, particularly in the US. Robert Christgau of the Village Voice explains that much of punk rock flirts with sexism by exploring rock and roll’s traditional subject matter. Christgau concludes that punk rock in general is “certainly no better place for women than any other rock scene, and in some crucial instances [is] worse.”[31] But he goes on to explain that this very fact is what makes certain groups so important. “In England, the Sex Pistols and the Clash direct their underclass rage, so often deflected toward women in rock and roll, right where it belongs, at the rich and powerful . . . ”[32]

An emphasis on aggressive arrogance calculated to shock is often the medium that punks utilize for expressing satire and parody. But it is this very lyrical content of punk rock that is the most controversial and contradictory. Social comment is often mixed with sexism, and even racism, sometimes in the same song, and even by groups that purport to have a progressive outlook. The contradictory character of popular ideology is nowhere more graphically displayed than in punk rock lyrics.

In the US sexism and racism have always been a part of the counter-culture which is dominated by white men. Since punk in the US is a counter-cultural phenomenon, and since violence and aggression are emphasized in punk, the tendency is for the sexism and racism to take on a more disturbing character. Songs like the Cortina’s “Fascist Dictator” (I don’t want love in any case, All I want to do is smash your face), and the Nun’s “Decadent Jew”[33] are only two of the most explicit examples of the regressive and reactionary tendencies in punk; but they most assuredly have their counterparts in other areas of popular culture, including country music. British working class culture is not without racism and sexism, and the British punk sub-culture exhibits its share of negative aspects. But in Britain important countervailing tendencies exist in Rock Against Racism and Rock Against Sexism to combat the negative developments that go unchecked in the US counter-culture.

Thus we cannot ignore the reactionary aspects of punk, but must recognize that they reflect attitudes that exist in society as a whole, ideas that once exposed can be struggled with. The key to assessing sexism, violence and racism in punk rock is to analyze to what degree such attitudes are dominant, and to what degree they reflect the general mood of the masses.

The positive elements of popular ideology should not be overlooked simply because the negative elements are so disturbing. It is through the processes of analysis and struggle, and our intervention by means of ideological practice, that the positive elements can be reinforced and the negative elements isolated and overcome. It is only a realistic assessment of existing ideology that will permit productive struggle to break down existing capitalist hegemony and to create an ideological hegemony that will serve all working people.

Finally, “The Clash and the Pistols have established social realism as an essential part of punk ideology, but this does not make their music the ’direct expression of the contemporary working class’.”[34] Contradictory mediations exist between society in general and the ideology of the audience and the musicians, mediations that shape the final lyrical content of punk songs.

Punk musicians, like any others, make their music with reference not just to their own individual or class experiences, but also to existing ideas about the meaning and purpose and potential of Rock. Punk is in its turn, seized on by the music business and given commercial meanings and interpretations which filter back to the musicians.[35]

Thus, the role of the culture and media industries becomes a crucial area for analysis.

They said we’d be artistically free, When we signed that bit of paper. They meant, let’s make a lotta monnee An’ worry about it later.–The Clash “Complete Control”

In analyzing popular culture the role of the capitalist culture and media industries is quite significant, but also quite contradictory. The culture industry can take what our minds conceive and turn ideas into advertising slogans, works of imagination into hit songs. “This is its overwhelming power, yet it is also its most vulnerable spot: it thrives on a stuff which it cannot manufacture by itself. It depends on the very substance it must fear most, and must suppress what it feeds on: the creative productivity of people.”[36]

The means and relations of musical and artistic production under capitalism have taken on a specific character that lends itself to control by, and profit for capitalists. The industries that have developed around records, concerts, films, television, radio and other cultural forms, all have their specific characteristics, but tend to reproduce similar types of relations, specifically in the separation of the cultural worker from the audience, and in the production of commodities to be consumed by isolated individuals. In discussing this process in the music industry, specifically in relation to the transformation of rock music in the 1960s from a “folk music” which was “listened to and made by the same group of people,” into an expansive commercialized commodity industry, Jon Landau of the Rolling Stone explains how rock and roll

came from the life experiences of the artists and their interaction with an audience that was roughly the same age. As that spontaneity and creativity have become more stylized and analyzed and structured, it has become easier for businessmen and behind-the-scenes manipulators to structure their approach to merchandising music. The process of creating stars has become a routine and a formula as dry as an equation.[37]

With the perpetuation of the star-cult phenomenon capital attempts to maintain control over the entire process of cultural production, from the production of records and movies in the studio, in total isolation from an audience, to the separation of the performer from the audience before, during and after a concert, spirited away by the “Goon Squad” (Costello) provided by the manager and record company to create and maintain a particular mystical image of the star.

But at the same time that the cultural industry manipulates its producers and consumers, it is also subject to contradictions from both directions. While the culture industry is vulnerable to the changing mood of the masses, which it works so hard and effectively to control through advertising, it is also vulnerable to changes in the standard of living of the masses. When inflation generates the need to choose between eating and seeing a movie, generally (but not always) the food industry gets the money before the entertainment industry. But even further, to make “new” culture the culture industry depends on people capable of innovation–in other words, potential “troublemakers.”

It is inherent in the process of creation that there is no way to predict its results. Consequently, intellectuals are, from the point of view of any power structure bent on its own perpetuation, a security risk. It takes consummate skill to ’handle’ them and to neutralize their subversive influence. All sorts of techniques, from the crudest to the most sophisticated, have been developed to this end: physical threat, blacklisting, moral and economic pressure on the one hand, overexposure, star-cult, cooptation into the power elite on the other, are the extremes of a whole gamut of manipulation.[38]

But these are short term practical approaches to a problem which in principle cannot be finally resolved. For on the level of production, even more so than in consumption, the cultural industry has to deal with partners who are potential enemies. In their attempts to proliferate an all pervasive popular culture, the industry simultaneously proliferates its own contradictions.

Thus, when we analyze the industry element of popular culture we cannot concentrate exclusively on the supposed, and often quite real conspiracies of manipulation, but must develop an understanding of areas where the industry is vulnerable to the progressive struggle to alter the status quo.

It is thus important to see that the punk ideology of the garage band was more than just an attack on the star system. It became a mechanism whereby the bands recorded themselves, without expensive equipment, and even distributed the recordings outside the established outlets. The Sex Pistols’ “God Save the Queen” moved to the top of the record charts in England even though the major record retail chains refused to handle it.

One important aspect of this development is that new independent recording companies grew up in competition with the huge multinationals. By now, though, most of the independents have either folded, been absorbed by the large conglomerates, or become conglomerates themselves. The main exception is Rough Trade records. Rough Trade is a cooperatively run independent that maintains an open policy toward musicians and recording, and released the debut albums of the all women band, the Raincoats, and Stiff Little Fingers. Rough Trade also has a progressive operating policy, where all staff receive the same wages, and successful struggles have been waged against sexist record covers.[39]

Interestingly enough, the earliest innovators in rock and roll had problems with major recording companies similar to those of the punks. Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry and the Drifters all started on small independent labels. Of course the multinationals got into the act once the new music had proven itself marketable and profitable.