ISJ 2 Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

From International Socialism 2:66, Spring 1995.

Copyright © International Socialism.

Copied with thanks from the International Socialism Archive.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for ETOL.

As I finish this article, Russian television is broadcasting pictures of the Chechen capital, Grozny, in the north Caucasus, making parallels with the level of damage to Stalingrad in 1943. Thousands have died under the carpet of Second World War fragmentation bombs dropped from the air. Boris Yeltsin’s Security Council is pumping out lies equal in their iniquity to the depths of Soviet propaganda during the Afghan war: the Chechens are supposedly blowing up the city, throwing babies out of windows, raping school teachers and castrating prisoners, while the Moscow press is all in their pay. The government has been starkly revealed to millions as a camouflaged politburo, led by the remote, disoriented figure of Boris Yeltsin. A postscript is being written into the Soviet Union’s bloody history of imperial aggression, the first major chapter in the ‘new’ Russia’s military aspirations.

Yeltsin’s firmest supporter in the Chechen war is a Nazi – Vladimir Zhirinovsky. The spectacular failure of market reform in Russia has led to a rapid growth of Nazi organisations, among which Zhirinovsky’s is the best known. This is an unpalatable conclusion, however, for the Western liberal establishment, who persist in referring to him as merely an aberration: ‘mad Vlad’, a ‘right wing populist’, ‘brute patriot’ and so on. Those who gave an ecstatic welcome to the wholesale application of the free market in Russia are naturally loath to admit that the collapse of these policies could threaten a rerun of the 1930s.

Many on the left in Britain and elsewhere are also confused about the Nazi right in Russia. For large numbers of socialists from Trotskyists to left social democrats the real fascist bogeymen are Yeltsin and the democrats, responsible for destroying the USSR, unleashing local nationalisms and forcing through the restoration of capitalism. Thus in October 1993 Ken Livingstone and the New Statesman, among others, defended vice-president Rutskoi and speaker Khasbulatov in their clash with the government, despite the latter’s reliance on extreme Russian nationalists, anti-Semites and armed, siegheiling Nazis in their attempt to take the Kremlin by storm. [1] Boris Kagarlitsky, a Russian theorist of social democracy well known to the Western left, has been calling Yeltsin a fascist ever since August 1991, while accepting the alliance of old style Communists with extreme nationalists as a potentially left wing force. [2] This knee jerk reaction, however, only confuses cause with effect.

An understanding of the rise of the Russian right is important in several respects. Firstly, there can be few clearer examples of the madness of the market system that has driven millions to despair across the former USSR. While opinion polls show that hatred of the former Communist regime runs deep, there is bitter alienation from Yeltsin and the champions of liberal economics who have presided over the quite obscene enrichment of the ruling class – the former nomenklatura – and a small number of financial parasites, at the same time condemning ordinary Russians to unspeakable misery. With each slowdown in the pace of collapse they claim to see a light at the end of the tunnel, yet each small breathing space is followed relentlessly by another gut wrenching spiral of inflation, slump and unemployment. In the absence of a powerful challenge to this process from below the Nazis have begun to fill the political vacuum.

Secondly, for a left largely demoralised by the ‘defeat of socialism’ at the hands of the East European masses, it is vital to grasp the reasons for the collapse of those regimes and to see that they represented no obstacle whatsoever to the horrors that are now unfolding in their place. In this sense the relative strength of the Russian Nazis, their origins in the old regime and their close links with its staunch defenders today are chilling confirmation of the analysis of Soviet Russia long associated with this journal. [3] The contradictions of Russian state capitalism are unresolvable in the context of the international economic crisis, thereby creating the potential for a right wing backlash.

The dynamic of the situation in Russia today is not one way. The last few years in Western Europe have also seen the re-emergence of a Nazi threat, but simultaneously a faltering but at times explosive development of workers’ struggle which has repeatedly thrown the Nazis back. The purpose of this article is to draw attention to a very real threat in Eastern Europe, to locate this threat in the failure of the market, and to assess the social forces that can resist it.

The logic pushing the Russian ruling class towards integration into the world market has already been analysed in detail over the last 30 years by Tony Cliff, Chris Harman and others. [4] Suffice to say that by the mid-1980s the internal contradictions of the command system had reached acute proportions with zero growth and the various elements of the economy irresponsive to central control, provoking yet another attempt at reform (Gorbachev had little original to offer – his was the fifth perestroika since Stalin died). [5] For the Russian bureaucracy, measures of decentralisation, of which market mechanisms have been a major element ever since they were touted by Malenkov in the mid-1950s, aimed to replace administrative with financial discipline at management level. [6] In the words of Georgy Khizha, the boss of a large military factory in St Petersburg who was brought into the government in May 1992: ‘Either administrative fear or material interest. There is no fear any more’. [7]

For six years the Russian leadership shuffled towards the market, hemmed in by the fear of losing control while driven on by the worsening crisis. The coup attempt of August 1991 was made by those in the ruling class who looked to China and South Korea as their model: market reforms under tight dictatorial control. As finance minister and coup leader Pavlov admits:

By the early 1990s we had worked out a theory and mechanism of market transformation. We followed so-called ‘salami tactics’ … to gradually, bit by bit, in an evolutionary manner slice sector after sector away from central planning and transfer them to a market regime. [8]

The beginning of ‘shock therapy’ in January 1992 marked a temporary speed up but not a radical break in this process. With Yeltsin’s popularity riding high after the coup, the young academic economist Yegor Gaidar, who had only left the Communist Party that August, was brought in to front a ‘kamikaze cabinet’ which, on 1 January 1992, freed prices on all but a few essential goods. Free market theory quickly clashed with hard reality. The Russian economy is highly monopolised, over half of industrial output coming from 1,000 large firms employing an average of 8,500 workers. [9] Autonomy simply allowed producers to jack up prices. In the words of Sergei Glaziev, minister of finance under Gaidar but now a fervent oppositionist:

Prices changed not so much under the influence of supply and demand, but instead were dictated by the monopolised parts of the market. And in so far as the majority of enterprises had no alternative supplier they were forced to accept almost any price rise on the resources they used. Prices are determined in most cases by the seller, and not the buyer. Thus a change in price on the output of one enterprise elicits a proportional change in price throughout the entire technological chain, with the restoration in a short time of the original relation. [10]

As a result, prices shot up, sometimes way above those on the world market, leading inevitably to a fall in output and the build up of company debt. There was one way of stopping this process: open up the economy to international competition, thereby forcing firms to charge a competitive price. According to the economic liberals this was to have a positive side: ineffective firms were to go bankrupt, thereby increasing the effectiveness of the economy as a whole. As the then finance minister and ultra-liberal Boris Fyodorov put it in 1993, ‘I am not one of those who takes pride in the slow-down in the industrial slump’. [11] But in a supermonopolised economy the bankruptcy of a few key firms has a knock-on effect throughout the rest of the country. As the Washington Post observed, ‘The government cannot take such a step [i.e. to push through bankruptcy law] without condemning millions to unemployment. In certain circumstances entire cities built around a single large firm will die’. [12]

Even Izvestiya, the trumpeter of market reform, got cold feet:

It is hardly wise to close down monopoly producers, especially if they produce raw materials or intermediate products, because after this all the users of their products along the technological chain will inevitably collapse. It is very difficult to identify among the vast number of loss making firms a few, the bankruptcy of which will not be devastating. [13]

Thus in the summer of 1992 the government backed down from its intentions and began massive financial support to cover industrial debts. At first it promised 500 billion roubles, which rapidly became 1 trillion and ended up as 3 trillion roubles. The result, as one economist put it, was rather like taking a sleeping pill and a laxative at the same time: the controls were taken off industry, while the printing presses kept churning out endless credit, leading to another leap in inflation.

Economic policy since then has had nothing to do with the ‘monetarism’ so beloved of Gaidar, Fyodorov and the IMF. Instead the government has balanced between winding up the pressure on industry by opening up to international competition, thereby effecting a gradual reorientation toward the priorities of the world market, while simultaneously stepping in to bail out the economy when things get critical. As Yevgeny Yasin, economic adviser to Gorbachev and Yeltsin and economics minister from October 1994, put it, the difference between the government’s economic policies under Gaidar in 1992 and under Chernomyrdin in 1994 was that Gaidar promised not to give industry any money, but did, while Chernomyrdin promised to give money, but didn’t. [14] Changes in government personnel have therefore been largely cosmetic, designed to influence international lending and aid agencies, and have tended simply to bring government rhetoric in line with its actual practice. After the marketeers Gaidar and Fyodorov resigned at the end of 1993, for example, the Financial Times declared it ‘the greatest disaster since Versailles’ and predicted hyperinflation, [15] yet in a few months inflation had fallen to its lowest level for three years.

The economic reforms have been all shock and no therapy. By May 1994 output was officially at 44 percent of its 1990 level and set to fall by another 16 percent in 1995 (following a fall of 19 percent in 1992 and 12 percent in 1993). This average figure hides the catastrophic collapse of certain sectors, such as light industry (down to 25 percent of its level in 1990) and machine tool building (30 percent down). The slump has hit the high-tech sectors hardest of all. Thus in 1991-1992 the output of computer numerically controlled machine tools fell twelvefold. Investment is roughly at 30 percent of its 1990 level and falling rapidly – down in the productive sector by 57 percent in the first half of 1994 in comparison with the same period in 1993. The authoritative journal Kommersant concluded that Russia had entered a ‘classical depression’ and ‘had taken on the obvious characteristics of a raw material economy’. [16]

So much for the ‘therapy’. As for the shock, the official figures show that incomes have been halved since 1991. The average figure masks huge income differentials, with incomes of the richest 20 percent rising by 30 percent in the first half of 1994 alone, while those of the poorest fell by 15 percent. Bread and potatoes are the staple diet for millions of Russians. In December 1993 39.6 million people lived on incomes less than the official minimum, while 77 percent of the population lived on less than twice this sum. About 13 percent of the population (19.3 million) lived on less than necessary for biological existence. Unemployment is estimated by the International Labour Organisation to be four to five times higher than official figures – a total by mid-1994 of 4.5 million fully unemployed plus the same again on short-time working or on compulsory non-paid leave. [17]

Privatisation by means of vouchers has meant – as originally intended – a further concentration of wealth and control in the hands of the privileged few, as workers with a pitiful number of shares have naturally opted to sell. As Finansoviye Izvestiya reported:

In the majority of enterprises in Russia a large owner is appearing, or has already appeared. Today it is they who are taking control. [18]

Over half Russia’s GNP is now produced in the ‘private’ sector, but the dependence of private firms on state-run utilities is still almost total.

At the same time corruption and speculation have been given a free rein. As the liberal economist Grigory Yavlinsksy aptly put it, ‘Our biggest mistake was that we freed this essentially mafia-like system from society, when we should have freed society from the system’. [19] Traders in non-ferrous metals on the stock exchange, for example, can make 2,000 percent profit in a week. The Washington Post estimates that up to $40 billion has been taken out of the country since 1991 and stashed in foreign banks. Instead of going to productive investment, government subsidies have been pocketed by directors and used to gamble on the financial markets. Yeltsin himself admits that bosses are paying themselves up to 10 million roubles a month – 30 times the average wage and 100 times the wage of many factory workers. [20] There has always been a colossal gap between rich and poor in Russia: the first Soviet millionaires appeared in the 1930s at a time when the average monthly wage was under 200 rubles. But the crisis today has enabled the rapid accumulation of extraordinary sums. The rich have so much cash they don’t know what to do with it: Moscow now has the highest concentration of casinos in Europe. The scrabble for wealth has led to daily gangland killings in the city.

With such obvious luxury cheek by jowl with abject poverty, it is quite understandable that Zhirinovsky’s promise to hang mafiosi in public places can find a hearing.

Yeltsin and the Democrats are not merely responsible for the immiseration of the Russian population. They have also blazed a trail for the authoritarian right by encouraging Russian nationalism in economic, military and foreign policy. Russia has simply not ‘capitulated to Western imperialism’ after the end of the Cold War: on the contrary, after a series of defeats at the hands of the Soviet population, the Russian leadership has systematically fought to claw back its position as a world military and economic superpower.

This is clear first and foremost from the economic statistics. Far from handing over the rights of Russian companies and mineral riches to foreign investors, Yeltsin has followed a fairly protectionist course. Thus in 1992 the government turned down major Western companies and granted rights to the Shtokmanovskoye gas field in the Barents Sea, the richest in the area, to a consortium of 19 elite Russian defence firms. In 1993 the massive gas monopoly Gazprom announced that it ‘categorically rejects the involvement of Western investors in major projects’. Similarly, an international tender for rights to the Udokan copper deposits, the largest in the world, was won by a Russo-Chinese firm in which the Russians had a controlling interest, against competition from BAP, Mitsubishi, Phelps Dodge and RTZ.

Little wonder, then, that by the end of 1994 the only major foreign involvement in the oil sector remained that of Conoco, which had invested a mere $300 million. Despite government attempts to attract foreign investment, by December 1993 the latter totalled only $7 billion, of which Germany accounted for 60 percent and the US for a mere 5 percent. Thus by the end of 1994 foreign capital in Russia was no more than that invested in Estonia alone! [21] When compared with the $109 billion dollars invested by Japan in the US by 1990, it is clear that Russia remains economically ‘independent’ of the West, while the latter is unlikely to risk investment in such a politically unstable region.

Russia has also run into stiff tariff barriers imposed by the US and the European Union, which are worried that cheap exports will drive prices down in an already depressed world market. One area, however, in which Russia has been actively carving itself out an international role is arms sales. Although in the last few years Russian weapons exports have almost halved and bring less than a quarter of the earnings of natural gas exports, [22] from the end of 1992 the liberal press devoted more and more attention to the restoration of military production. In January 1993 presidential adviser Mikhail Malei announced that the government is observing a ‘new concept’, according to which the defence sector will not destroy the country, but rather feed it. ‘Whether or not this pleases the pacifists,’ he said, ‘this is the law of the market’. [23] A month later Yeltsin announced:

Not long ago I was in India, and I began to doubt that it is necessary to reduce military production. There is a colossal market there for our military products, and then we wouldn’t have to re-convert defence factories back from saucepan production. [24]

In recent years Russia has concluded a series of major arms contracts with India, China, Iran, Turkey and the Middle Eastern countries, all in the face of stiff US competition and, in the case of the sale of rocket motors to India, the threat of a 50 percent reduction in US economic aid. [25] In October 1994 defence minister Grachev announced that military-civil conversion should be stopped altogether in favour of a massive increase in arms sales. [26] In this area, Yeltsin’s government is simply fulfilling one of Zhirinovsky’s main demands.

Russia has also gradually increased its military presence in the countries of the former USSR, seeking to overcome its ‘Afghan syndrome’, the domestic population’s hostility to the use of Russian troops since the defeat in Afghanistan.

Yeltsin made his intention clear right from the start. On 26 August 1991 (less than a week after the coup attempt) Yeltsin’s press secretary announced a possible revision of Russia’s borders: the Russian leadership sent the Ukraine and Kazakhstan a note threatening to annex territory in these republics if they didn’t sign a new Union Agreement. [27] Here the leadership of the ‘new’ Russia fairly accurately repeated the calls of the far right Soyuz group of parliamentary deputies led by Colonel Alksnis, who threatened to take Latgalia from Latvia, the Virumaa region in north east Estonia, and to annex north Kazakhstan. In fact, Russia’s leaders clearly went beyond their Soyuz companions. On 27 August 1991 Gavriil Popov, then the mayor of Moscow, appeared on television talking not only about possible annexations of the Crimea and eastern Ukraine, but also Odessa, Izmail and virtually the entire Black Sea coast. Russia has kept up its military pressure on the Ukraine through its claims to the Black Sea fleet, which it wants in order to match the Turkish naval build up in the region. [28]

Yeltsin picked up where Gorbachev had left off in Tbilisi, 1989, Baku, 1990, and Vilnius, 1991. In November 1991 he decided to send in the tanks to crush the independence of Chechnya, the tiny but oil rich republic in the north Caucasus. Russian troops met such mass resistance that they turned and fled, the operation ending in a fiasco. From then until December 1994 Moscow acted more circumspectly, its intervention taking place under the flag of ‘peacekeeping forces’. But the following pattern emerged: everywhere Russian troops constituted the bulk of the peacekeeping forces, they were brought in only after the main fighting had taken place and therefore had little positive influence on the severity of bloodshed, they showed a clear preference for one of the conflicting sides (or supplied both sides with weapons so as to exhaust their economies and force them towards Moscow), they often relied on local unofficial armed gangs, and everywhere they have left untouched the underlying problems originally provoking conflict. [29]

All the above listed elements were present in the Russian interventions in the Georgian republics of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, which enabled Russia to sign a deal in March 1994 resurrecting Russian military bases on Georgian territory. In the words of Zbigniew Brezhinski, the former US security chief, ‘Just ask Shevardnadze [the Georgian leader] what he thinks about the sources of the [Abkhazian] conflict, and he’ll tell you that the Russian army initiated the conflict and used it so that it could later say: we will mediate, but give us three large military bases on the Turko-Georgian border’. [30] The pattern was faithfully repeated in the puppet Dnestr Republic (Moldova) in July 1992, which vice-president Rutskoi called Russia’s Grenada, [31] and again in North Ossetia in November the same year, when Russia chose to back the local regime in driving 70,000 Ingushis from their homes in the area near Vladikavkaz that had been annexed from Ingushetia by Stalin in 1944. A taste of what happened after the arrival of Russian ‘peacekeepers’ is given by an eyewitness journalist’s report:

The Ossetian volunteers tumbled out of their cars, formed a line and set off along the village street, raking the houses and yards with fire. On a few gates white rags marked Ossetian homes, which were left alone. As for the others – the gate is kicked in and they open fire in the corridor. Petrol is thrown on the walls, a match, and it explodes in flame. And the line moves on. A kick, bullets, explosion, flame. Kick, bullets, explosion, flame … [32]

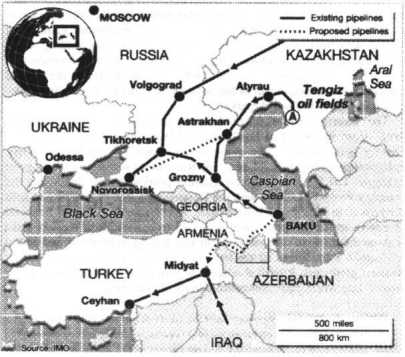

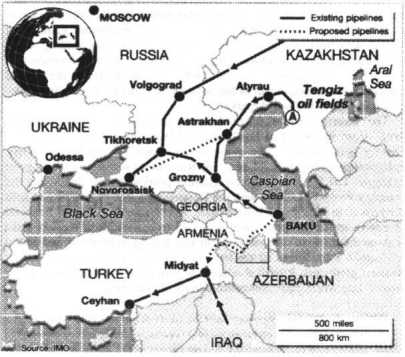

North Ossetia was then turned into a military outpost for Russia in the Caucasus, with a quantity of arms per head of population the highest in the world. [33] It was from its Ossetian bases that Russia launched its second attempt to invade Chechnya in December 1994. Since the fiasco of 1991 Moscow had kept up economic and military pressure on Grozny, looking for an opportunity to unseat its leader, General Dudayev, and put a more compliant figure in his place. In the summer of 1994 a direct threat to Russian hegemony in the Caucasus appeared in the shape of Azeri claims to the fabulously rich oil fields of the Caspian Sea and its moves to involve British, US and Turkish oil companies in developing the reserves. Pipelines from Baku run through Georgia and Armenia, already within the Russian ambit, and through Grozny, which is also the site of major oil refineries. In September Azerbaijan dropped a bombshell by including Iran in a deal to reroute oil to the south, threatening Russia’s pipeline monopoly. (see the map on p. 14, below)

Bringing Chechnya to heel became an economic and strategic necessity for Moscow, which stepped up its funding of the Chechen military opposition. Ruslan Khasbulatov, himself a Chechen and leader of the October 1993 attempt to storm the Kremlin, was given Russian cash and arms to increase Moscow’s influence and establish himself as opposition leader. The Federal Counter-Intelligence Service, successor to the KGB, recruited Russian officers to fight in Chechnya. Doku Zavgayev, Chechnya’s former Communist boss overthrown by a popular uprising in September 1991 after backing the Moscow coup leaders, was brought into Yeltsin’s administration and put forward as a leading candidate to take Dudayev’s place.

After the failure to invade Grozny using proxy forces, Yeltsin opted for a full scale mobilisation of Russian troops and razing Chechen villages and the centre of Grozny to the ground, which earned him the active support of Zhirinovsky and much of the extreme right. In the meantime, the three year long civil war with the Islamic opposition in Tadjikistan continues, with the involvement of 25,000 Russian troops.

Moscow’s growing confidence to assert its claim to the role of military policeman in the former Soviet bloc has been accompanied by a general hardening of its foreign policy. In 1992 statements by leading government figures about ‘friendly relations’ with Iraq and calls for sanctions against Croatia allowed Izvestiya to talk of ‘a clear drift in the foreign ministry’s approach’ to foreign policy as a whole. [34] In March 1993 Yeltsin announced, ‘The moment has come when the respective international organs should grant Russia special powers as the guarantor of peace and stability on the territory of the former Soviet Union’. [35]

The discovery in early 1994 of a Russian spy, Aldridge Ames, in the leadership of the CIA dramatically confirmed that Moscow was continuing its former Cold War behaviour. In the UN and the CSCE Russia and the US have increasingly clashed over Yugoslavia and the role of the NATO alliance in Eastern Europe.

If Russia is really flexing its imperial muscles, how are we to view the end of the Cold War, the collapse of the USSR and Russia’s initial orientation on the US?

When perestroika began, the USSR’s improved relations with the West were dictated by the economic crisis which had been bearing down on the country since the late 1970s. In the words of Sergei Karaganov, deputy director of the Russian Academy of Science’s Institute of Europe and member of Yeltsin’s Presidential Council:

The Soviet leadership tried to break out of the system of confrontation that had built up as a result of the Cold War and which was extremely unfavourable to the USSR. The Soviet Union with its weak and unreliable satellites was forced to stand up to a coalition of the world’s most advanced countries. Moreover, by the end of the 1970s it was clear to many in Moscow that the ‘buffer’ created by Stalin in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe offered no real security but was very costly … Finally, the East European empire was expensive in the direct sense – Moscow spent enormous sums on subsidising neighbouring countries. [36]

But in addition to these negative considerations, there were also positive factors pushing the politburo to reform its relations with the outside world, namely the ‘desire to achieve access to the Atlantic markets for technology’. [37] According to the Reform Foundation of Stanislav Shatalin and Vadim Bakatin, the Soviet leadership hoped that by losing its status as the imperial metropolis it would make big economic gains. [38] As Ruslan Khasbulatov put it in 1991, ‘Another factor was leading to the creation of a braking mechanism in the economy – the transformation of productive isolationism into autarchy, isolation from the world market … [the consequence] of the destructive concept of "absolute independence" from the world market’. [39]

The ‘destructiveness’ for the Soviet economy of ‘absolute independence from the world market’ followed from the inability of a single country – even one as large as the Soviet Union – to match world technological progress in all spheres. The Russian oil sector provides a good example. The US giant Amoco recently proposed joint drilling in the complex Priobsky oilfield with the Russian firm YuNG, offering to split the gain 20 to 80 with the Russian side. Apart from this obvious financial incentive to the Russian state, reluctant to exploit the Priobsky field without the US firm’s financial might and drilling technology, and on top of Amoco’s readiness to contract out the rig construction to major Russian producers, Russia also needs to turn its newly privatised ‘seven sisters’ into world class competitors in the oil business:

Without the Priobsky contract YuNG is likely to get nowhere. Only such a project can attract big investment like a magnet, enabling a breakthrough in oil refining and petrochemicals. Russia cannot afford the luxury of middle-category oil companies and average pipelines. This is … a question of geopolitics … The new independent states of the post-Soviet south are trying to re-orient the flow of raw materials (mainly oil and gas) to by-pass Russia. [On the other hand,] major contracts and deals will bind them to traditional markets, co-operative links and sales routes. [40]

Thus according to the original plan, sloughing off its Soviet imperial skin should have enabled Russia to leap ahead economically. Of course, no one at the top expected the empire to blow up in their faces – a consequence of 60 years of national oppression at Russian hands. On top of that, the world slump meant that no one was eager to welcome Russia into the world market. This is why the balance sheet of perestroika for the Russian ruling class has been so negative.

|

However, as the above discussion reveals, there was no ‘capitulation’ to the Americans. When the Russian ruling class stopped reeling from the defeats inflicted on it by the population after 1989 it set about strengthening its position both at home and abroad. The big show of post-Cold War friendship between Russia and the US was necessary to both sides. The Kremlin needed to persuade its people that the bad old days were over and that reform would take them to an affluent market future:

Reformers in these [East European] countries do not invite foreign advisers because they do not know what to do. They invite them in order to clearly mark the direction of the course of reform. Moreover, in the eyes of the educated public, an authoritative Western adviser can put an important ‘seal of approval’ on any new reforms. [41]

Bush and Clinton, on the other hand, could scarcely continue to talk of a Communist threat, and they constantly admonished American workers for complaining while the Russians were prepared to suffer so much just to duplicate the US market system. [42] In fact, US ‘humanitarian aid’ to Russia was a tiny drop in the ocean, and almost all of it came with strings attached, such as stipulations to pay US transport firms to deliver the aid. [43] General US acquiescence to Russia’s proposed role as policeman in its backyard points to fears of the possible ‘Yugoslavisation’ of Eastern Europe. As Clinton himself put it, ‘Imagine the consequences for Europe if millions of Russian citizens decide that they have no other option than to flee to the West’. [44]

Indeed, it is an open question whether or not US imperialism has ‘gained’ much from the collapse of the USSR. [45] Talk of an ‘end of history’ and the victory of ‘liberal democratic’ capitalism cannot disguise the crisis facing both Washington and Moscow. The latter’s response to this crisis – the stepping up of imperial propaganda and the defence of ‘Russian national interests’ – is a mark of the failure of market reform, a major concession to the far right, and therefore an encouragement to it.

Nothing has done more to strengthen the trend towards authoritarianism than Yeltsin’s record on democracy: he has disgraced the concept and fed the yearning for a ‘firm hand’ to restore order.

When Yeltsin stepped onto a tank outside the Moscow White House on the afternoon of Monday 18 August 1991 to lead the opposition to the coup, he dramatically asserted his image as the champion of democracy against Communism. The ensuing battle on the streets was a very real battle against a very real enemy: the programme of the State Committee for the State of Emergency announced a ban on all ‘meetings, street demonstrations, and also strikes’. Tens of thousands of Muscovites risked their lives to stop the tanks. Those politicians, however, who spent the coup safely locked up in the parliament, acted in sharp contrast with their professed democratic ideals. As Gavriil Popov wrote a year after the coup, the Russian leadership traded support for Yeltsin with concessions to leading figures in the state and the army, such as General Grachev, who were wavering: ‘Considering that the storming of the White House [by Grachev’s crack troops] didn’t take place and that Grachev became Russian minister of defence, it is easy to conclude that both sides honoured their obligations to the full. In the future it will be clear how many more such negotiations took place’. [46]

Instead of pushing home the victory over the putchists, Yeltsin did everything in his power to restrain the crowds on the streets and to make sure that there were no repeats of the 1989 scenes in East Berlin, for example, when thousands stormed the building of the Stasi (secret police) and seized files. Popov adds in this respect:

Yeltsin’s main contribution as a politician is that he completely rejected the idea of turning the victory over the [putchists] into a wholesale purge of the former system, into a revolution of the Leninist type … In contrast to the leaders of the Russian Revolution of 1917, who were personally absolutely hostile to the former Russian ruling class, Yeltsin could see the reform-minded sections of the party and other Soviet structures as a potential reserve … Without the support of the Russian president I, as mayor of Moscow, could never have restrained the ‘revolutionary’ anger of the masses. [47]

Immediate indications of how shallow were the changes that Yeltsin’s victory brought about were the fact that no dissident figures were brought into government as in Eastern Europe.

Yeltsin’s pragmatic attitude to democracy soon manifested itself. In November 1991 he postponed local elections and appointed governors to run local administrations, while his adviser Sergei Stankevich announced, ‘A period of root-and-branch reform is no time for the flourishing of parliamentary democracy’. [48] Like Gorbachev before him, Yeltsin brought hardliners into his immediate entourage, creating the unaccountable and all powerful Security Council under the hawkish Yuri Skokov. Yeltsin went so far in taking power from parliament and concentrating it in his own hands that his new 1993 constitution enshrining presidential authority in law was welcomed by Zhirinovsky. In 1994 the renamed KGB and the police were given ‘stunning new powers, about which the militia could only dream in pre-perestroika times, or even under the "firm hand" of Pugo [one of the August 1991 coup leaders]’. [49]

After the coup attempt the failure of reform to deal with the crisis quickly opened up splits among the Yeltsinites. Though dressed up in terms of democratic principle, even Izvestiya finally had to admit that the divisions in the leadership were nothing but ‘a struggle for power’. [50] While the parliamentary opposition to Yeltsin made no secret of its fondness for authoritarianism, the president’s supporters in turn continually referred to the need to limit democracy. Thus in the run up to the April 1993 referendum on presidential power Izvestiya ran a story headlined Authoritarian Government Is Better Than No Government, and argued that ‘in situations like that in Russia we must seek our salvation in strict, even authoritarian government’. [51]

On 21 September 1993 Yeltsin disbanded parliament, which had been elected during the high point of the pro-democracy movement in 1989 and 1990. In the morning of 4 October tanks began shelling the White House – an isolated civil war raged in the centre of Moscow for a day. [52] In the aftermath of the fighting censorship was introduced and papers appeared with blank spaces. A two week state of emergency in the capital saw a curfew imposed and the army given a free hand. According to official figures a staggering 89,250 Muscovites were arrested during this period – almost 1 percent of the city’s population. Many of them were beaten up and abused. The army and militia led pogroms against blacks from the southern republics and drove 9,776 people out of the city, the vast majority non-Russians. [53]

After the October events the Democrats renewed their calls for an end to democracy. Gavriil Popov announced:

I believed and believe now that the parliamentary system in its classical, all-embracing, popular form is unacceptable for Russia in the transition period … The bourgeois countries that have gone through similar stages of development had no systems of direct universal suffrage. [54]

Valeria Novodvorskaya, the outspoken leader of the Democratic Union, recommended ‘enlightened authoritarianism’ under Yeltsin, because ‘the people are not ready for full democracy’. [55] A year later the leading liberal daily Segodnya declared that voting rights should be restricted to 5 to 10 percent of the population:

The country needs order, and not a parliament for good marks in some Council of Europe or other. Once again we must repeat the well-known truism: in a mad-house the doctors are not elected. [56]

Given the close similarities between the government’s policies for the economy, the empire and democracy, and the frequency with which leading Yeltsinites have defected to the opposition, it is hardly surprising that Yeltsin’s leadership has compromised with the Russian nationalists, and vice versa. Rather than face civil war within the bureaucracy again spilling onto the streets, Yeltsin soon agreed to an amnesty for his opponents in October 1993. Though Yeltsin has yet to resort openly to the nationalist card, he has made conciliatory gestures to the Nazis and brought extreme right figures into the government. Thus in February 1994 the nationalities minister Sergei Shakhrai sent greetings and an offer of mutual co-operation to the World Congress of Russian Communes, well known for its Nazi sympathies. [57] The press minister Boris Mironov was forced to resign in September 1994 after a scandal concerning his demands for a centralised, government controlled media, and for his remark, ‘I am a strict nationalist. Internationalism is the devil’s invention. If Russian nationalism is fascism, then I am a fascist’. [58] After his sacking Mironov went straight to join General Sterligov’s Russian National Assembly. But Mironov joined the government as protégé of the speaker of the upper house Shumeiko and the information minister Poltoranin. Poltoranin, a leading member of Gaidar’s party, ‘Russia’s Choice’, has made little secret of his nationalist and anti-Semitic sympathies, announcing to a Jordanian newspaper that Russia was at risk of occupation by Zionist forces and declaring in a television interview that the Russian press talked in ‘the Hebrew of the prison camps’ and was ‘Russophobic’. [59]

The war in Chechnya brought home the underlying similarity between Yeltsin and the opposition, especially when Yeltsin’s only backing was from Nazis and Boris Fyodorov’s tiny liberal fraction. The government commissioned Alexander Nevzorov – scandalous monarchist and darling of the right who lost public favour when he made a film praising the 1991 invasion of the Baltic States – to make a film of Chechnya to ‘correct the information balance’ in Russian media reporting of the war. [60]

As a result of this betrayal by Yeltsin and the Democrats, democracy has become a tainted word in Russia and the system of electoral participation has been discredited, leading to disillusion and political apathy on a grand scale. At Russia’s first multi-party general elections in December 1993 only 53 percent of the electorate bothered to vote. At city wide local elections in Russia’s second city, St Petersburg, in March 1994 the vote had to be extended for a second day while cars with loudspeakers toured the streets and electoral rights were suddenly granted to students and soldiers in order to achieve the statutory minimum 25 percent turnout.

The shift in public attitudes to Yeltsin was already clear by October 1993. In August 1991 the great majority of Muscovites who came to face the tanks were also uncritically pro-Yeltsin. But by the time of the next coup the numbers prepared to defend him were minimal. A few days later Alexander Minkin, the popular journalist for Moskovsky Komsomolets, wrote, ‘People came [in answer to Gaidar’s call for assistance]. Not out of love for Yeltsin and Gaidar, but out of contempt for Khasbulatov, Makashov and Anpilov [the coup leaders]’. [61]

The combination of rapidly worsening living standards with passivity and disillusionment in the Democrats led to a growing nostalgia for the past and a search for scapegoats among the national minorities. This was summed up by Nezvisimaya Gazeta straight after Zhirinovsky’s election success in December 1993:

Did the Democrats really think that their hurriedly adopted wolf’s clothing would look more attractive to the chauvinist electorate than the tried and tested mask of Zhirinovsky’s party? Did they really think that they could shell their own parliament and at the same time command a majority? [62]

The Nazi label is a controversial one, both in Russia and elsewhere. Nazism differs from other reactionary movements firstly in terms of its core social base in the middle class, caught between the hammer and the anvil of the workers and the bosses, and secondly through its attempt to mobilise this social base into a mass fighting force directed against workers. [63] When Nazism is in its early stages, therefore – as it is in many countries of Western Europe today – these two distinguishing features are present only in embryo and hard to identify conclusively. Nor do reactionary movements go forward on some smooth and ever rising path to absolute power; they suffer set backs and crises, which also affect their leaders and their politics, making them twist, turn, hesitate and regroup. Furthermore, the scale of social conflict in Europe is not yet anywhere near that of Germany of the early 1930s or Italy after the First World War, so today’s Nazis are often careful to mask their true intentions as they fight for political hegemony on the right. Finally, many would argue that the world has changed so much since the inter-war period that it is foolish to talk of a repeat of the 1930s, a social crisis of such catastrophic magnitude is ruled out, and that today’s extremists are therefore merely playing at Nazism.

The situation in Russia today confirms, however, that the depth and intensity of social crisis have created perhaps the greatest social potential for a Nazi resurgence in Europe, along with a large number of individuals and organisations consciously attempting to go down Hitler’s road.

The following survey of the Nazi right in Russia and the social milieu in which it is trying to build does not pretend to be comprehensive. There are approximately 90 extreme right newspapers in Russia today representing their own respective groupings. [64] Here we shall only look at the main ones.

On 12 December 1993, barely two months after government tanks had shelled the parliament building in Moscow, Russians went to the polls for the first multi-party general elections since the civil war. Late that same evening millions tuned in to watch the sumptuous TV extravaganza organised by Boris Yeltsin’s cabinet to celebrate its sweeping electoral victory. As the results came in, the show rapidly turned to farce: Vladimir Zhirinovsky, leader of the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR), had picked up nearly a quarter of the votes – the Democrats only 12 percent.

Zhirinovsky first appeared on the political scene during the Russian presidential elections of June 1991, when his promise to ‘defend the rights of Russians in all territories’ and ban all political parties won 6 million votes. By then he had already attracted the attention of other Russian Nazis, who saw him as a potential springboard into ‘big politics’. Thus in spring 1991 Zhirinovsky appointed the leaders of the National-Social Union (NSU), Yuri Vagin and Victor Yakushev, to responsible posts in the LDPR in return for their assistance in his election campaign. [65] Vagin was known for his record as a monarchist dissident in the 1960s, while Yakushev was a leading member of Pamyat (the main Nazi outfit in the early years of perestroika), who declared in a 1991 interview that his political idols were Genghis Khan and Adolf Hitler. [66] At the time the NSU was a tiny Nazi grouping, one of several to emerge from Pamyat, looking for a means of building support.

The NSU left Zhirinovsky in early 1992. First it collapsed and then it re-formed as the National Front. Other Nazis had far a less casual and opportunistic relationship with Zhirinovsky. From 1991 his ‘shadow cabinet’ included two young Nazis, Andrei Arkhipov and Sergei Zharikov, soon to be joined by Eduard Limonov, who together played a determining role in the organisation’s politics.

Arkhipov and Zharikov edited one of the LDPR’s newspapers, Sokol Zhirinovskovo (Zhirinovsky’s Falcon), and ran the party’s uniformed and militarized youth wing, the Falcons. In 1992 and 1993 there were five issues of Zhirinovsky’s Falcon, each with a print run of 50,000. Alongside regular articles by Zhirinovsky himself there is extensive material of a purely Nazi character, much of it written by Arkhipov and Zharikov themselves. A few quotes will suffice:

Today it is for some reason unacceptable to talk about the economic successes of the Third Reich, the cultural achievements that National Socialism gave the world. But no one can deny them! … Blood and soil are the two main principles of state formation; we need to form defence and storm groups, national socialist detachments. Russia is the last outpost of the white civilisation. We need a new racial genesis, as a result of which the caste of Russo-Slavs will revive the ancient Knowledge of Nature as an Aryan cosmos. The Day of the New White Race is dawning. We must form a United Nations of Peoples of the White Race. The final aim of Zionism is the economic and political domination of Jewry throughout the world and is the direct consequence of the national character of the Jewish people. [67]

As the paper of the military wing of the LDPR, it was aimed at these core party activists, so talk of ‘national socialist detachments’ was not just wishful thinking.

But Zhirinovsky’s reliance on these self confessed Nazis went much further than simply allowing them to edit his newspaper and educate his stormtroopers. Arkhipov and Zharikov had a key political role in the party. As Arkhipov remarked to the newspaper Izvestiya:

Almost all the slogans used by Zhirinovsky were thought up by myself and Zharikov. Ten minutes before he would speak to a crowd we would write out slogans in big letters, for example, ‘America: give us back Alaska!’ Zhirinovsky, in front of whom I would hold up the slogans, would then pick up on them and expand them. [68]

This is not pure exaggeration: Arkhipov’s statement is corroborated by Eduard Limonov in his book on Zhirinovsky, [69] which provides revealing insights into the LDPR. Limonov is a household name in Russia. A writer exiled in the Soviet period for his views, his return to Russia in 1992 coincided with the publication of his sexually explicit and semi-autobiographical novel It’s me, Eddy, which was very popular among young people.

Limonov, Arkhipov and Zharikov split from Zhirinovsky in November 1992 to form the Right-Radical Party, [70] an openly Nazi outfit whose journal Ataka appears with a swastika on the cover. Limonov describes the split as follows: in September 1992 he and Zhirinovsky visited Le Pen in Paris:

Le Pen frowned [and] suddenly began to warn Zhirinovsky about ‘young men in leather jackets who will pull your movement towards national socialism. The sooner you get rid of them the better’. [71]

Zhirinovsky took Le Pen’s tactical advice. The leadership of the LDPR split. On 14 November Arkhipov, Zharikov, Limonov and four other members of the shadow cabinet (only Zhirinovsky himself and two others did not attend) met at a luxury dacha (country house) outside Moscow to form the Right-Radical Party. However, the others eventually decided to return to the fold, leaving the ‘young men in leather jackets’ to fend for themselves, accusing Zhirinovsky of bureaucratism, lack of radicalism and, of course, ‘Jewish blood’. [72]

One should be clear that this was no split between supporters and opponents of national socialism. In the first place, Zhirinovsky has never said that he expelled his former colleagues because they are Nazis, but because ‘they weren’t serious’. [73] On the other hand, Zharikov has stated that ‘the Leader [Zhirinovsky] reads Hitler, Himmler and Goebbels in his free time’. [74] Rather the split in the LDPR reflects tactical differences between Nazis throughout Europe over the relationship between the core of stormtroopers and the softer periphery that extends all the way to the passive voter. Zhirinovsky’s flexibility has enabled him to scale the heights of Russian politics and to have a real impact on events, standing him in good stead for future crises when the emphasis can shift to the Nazi core, to be used as a battering ram against workers’ organisation. He has been careful about advertising his sympathy for Nazism, because he is operating in a country that still remembers 30 million dead as a result of the war with Hitler. It is still early for him to find widespread acceptance for Nazi explanations of the war – ie that Hitler was the victim of a Zionist plot.

But the record of Zhirinovsky’s collaboration with people who do not attempt to hide their views is conclusive when considering the existence of a militarised core (the Falcons have not been disbanded) and the mass of circumstantial evidence concerning Zhirinovsky’s Nazism: his threats to nuke Japan and the Baltic States, to ban all political parties and strikes and extend Russia’s borders to the Indian Ocean, his autobiography which mirrors so much of Mein Kampf, his vicious anti-Semitism and so on. All this is quite apart from the obvious delight among activists in other Nazi groups after Zhirinovsky’s election success in December 1993 – at Moscow State University they gloatingly told anti-Nazi activists, ‘We’ve won!’

Since Zhirinovsky’s rise to prominence there have been several reports claiming the LDPR is a puppet of the KGB. The mayor of St Petersburg, Anatoly Sobchak, for example, implicates Gorbachev himself. Leading politicians such as Galina Staravoitova and Alexander Yakovlev have also stated that the KGB formed the LDPR in an attempt to create a pocket opposition when the Communist Party was on the verge of collapse. [75]

These claims do not conflict with the circumstances of Zhirinovsky’s political past. Educated at an elite language university and allowed to travel abroad, Zhirinovsky was clearly no stranger to the KGB. His party was the first to be registered after the removal of the one party clause from the Soviet Constitution, and he was immediately granted access to central venues when other opposition parties were still semi-legal. An invitation to Zhirinovsky to join Gorbachev on Lenin’s mausoleum in November 1990 for the annual parade to celebrate the revolution is still on display in the Museum of the Revolution just across from the Kremlin.

A party such as the LDPR, claiming to be liberal but against ‘democratic excesses’ and uncritical of the KGB could clearly have met the requirements of the Soviet state at a critical juncture. Without doubt Zhirinovsky enjoys widespread support in the police and army today. But the LDPR is far from being the obedient tool of the Russian secret services that can be safely wound up should it get out of control. Zhirinovsky’s political origins say more about the nature of the Russian state than about the party that he leads.

Since the events of October 1993 the name of Alexander Petrovich Barkashov has appeared regularly on Russian television and in the national press. In this sense the October attempt ‘to take the Kremlin by storm’ (Rutskoi’s appeal from the White House balcony) played the same role for Barkashov as the Beer-Hall Putsch for Hitler – it shot him to national prominence.

In 1990 Barkashov’s Russian National Unity (RNU) organisation split from the main Nazi outfit at the time, Pamyat (Memory), which fractured into half a dozen groups at the end of the 1980s. [76] RNU is distinguished from other Nazi groups by its blackshirt uniform and its use of the swastika as ‘the symbol of the future Russia’. [77] In October 1993 several dozen of its members played a leading role in the defence of the parliament and shocked Russian public opinion by parading up and down outside the White House wearing swastika armbands and giving Nazi salutes. Barkashov’s publications make it clear that Russia awaits the same ‘national reawakening’ that took place in Germany in 1933, Italy in 1922 and Spain in 1936. [78] RNU propagates a particularly foul brand of anti-Semitism.

Barkashov has achieved what Zhirinovsky and others have yet to accomplish: he has put significant numbers of young men in uniform and set them marching. During the October by-election campaign in a Moscow suburb election meetings attended by all candidates were packed with hundreds of youths in combat gear and swastikas, who drowned their opponents down with shouts of, ‘Less people, more oxygen!’, and ‘Zionism shall not pass’. [79] Barkashov’s candidate promised to introduce eugenic birth programmes and to ‘exterminate’ homosexuals. He won almost 10,000 votes (5.9 percent).

Barkashov’s organisation is extensive. According to a high ranking member who turned against the organisation:

There are over 10,000 ‘brothers-in -arms’ [the highest of the three membership levels in RNU, forming the organisation’s nucleus] throughout Russia. In Moscow alone there are over 500 people. There are over half a million fellow campaigners’ and ‘supporters’. But there are also ‘sympathisers’ – who can count them all? RNU is slowly but steadily gathering strength. People in the police, army and high-placed ministerial figures are currying favour with RNU … Barkashov’s people enjoy particular sympathy among leaders of the National Salvation Front, Labouring Russia, national-bolshevik groups, the nationalist element of the Orthodox priesthood, some deputies to the State Duma and even heads of the administrations of cities and oblasts. [80]

This may not be an exaggerated assessment (although it is rather too similar to that given by Barkashov himself, and the figure of 10,000 core members doesn’t tally with the much lower figure for the capital itself), and its latter half is certainly accurate. This makes RNU the fourth largest political party in Russia after the LDPR. In March 1994 Barkashov established the National Social Movement as a Nazi trade union along with Alexander Alexeyev, leader of the Confederation of Free Trade Unions of Russia, one of the largest independent trade union federations in the country, claiming over 200,000 members. In a joint statement they declared that ‘the class struggle between employers and wage workers is a fanatical Marxist-Zionist invention. The interests of employers and workers should not clash’. [81] According to one report, the Nazis have a significant base in the massive Severstal steel plant in Cherepovetsk and have begun to establish contact with Vorkuta miners. [82]

In view of its openly Nazi ideology, why is RNU so successful? Barkashov seems to have grasped that the key to success in mobilising people demoralised and disorientated by the crisis is brute, naked force. His organisation is held in awe by nationalist opponents of the Yeltsin regime, who are spellbound by the uniforms, the muscular young men, their certainty and heroic image. This has enabled Barkashov to reach mutual agreement with General Sterligov’s Russian National Assembly, Stanislav Terekhov’s Union of Officers and other nationalist organisations and to begin to unite the myriad nationalist groupings. Most significantly, the big Moscow weekly Zavtra, edited by Alexander Prokhanov, who sees his role as uniting the various currents on the far right, has become a propaganda organ for Barkashov, gushing praise for the RNU, repeating its sordid lie that Israeli troops led Yeltsin’s attack on parliament in October 1993 and so on.

RNU strikes fear into its opponents and makes its uniformed supporters feel that they deserve respect. On a somewhat more prosaic level, one of the latter says that no one asks them to pay when they get on the metro: ‘And in the train itself everyone squeezes up and they all sit quietly until you get off’. [83]

There are several umbrella organisations in Russia that bring Nazi, monarchist and extreme nationalist groupings together with supporters of the former regime, people and organisations that call themselves Communist. The best known of these is the National Salvation Front, whose secretary was for a time the leader of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, Gennady Zyuganov. The front has been responsible for massive demonstrations in Moscow of hundreds of thousands of people, sometimes leading to bloody clashes with the police. Here you can find placards of Stalin rubbing shoulders with the black, white and gold flags of the Romanovs. This phenomenon has become popularly known as the ‘Red-Brown’ movement, uniting the ‘Reds’ with the ‘Brownshirts’.

Politically these apparently diverse forces are agreed in their demand for an end to democracy, the introduction of a state of emergency (the programme of the August 1991 putschists), an end to military-civil conversion in the arms industry and the resurrection of Russia as a great imperial power.

The ideological cement of the movement is Great Russian nationalism. Take the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF), for example, an organisation that numbers over half a million members. Gennady Zyuganov’s latest book, Great Power (1994), claims to set out the central planks of the CPRF’s politics. Zyuganov makes no attempt to distinguish nation from class, and offers but one small apology to Marx, who apparently considered his theories to be applicable only to Western Europe, and to Lenin, who apparently argued to unite all classes so as to stand at the head of the nation. [84]

For Zyuganov, Moscow is to become the ‘Third Rome’, ‘Holy Rus’, destined to fulfill the tsarist trinity of ‘autocracy, Orthodoxy and nation’. Russia must fight a ‘national liberation struggle’ against ‘transnational, cosmopolitan forces’ of the ‘world oligarchy’, against ‘naked russophobia’ and ‘crazed persecution of Russian writers’, to resurrect the USSR, ‘the historical and geopolitical inheritor of the Russian empire’. He talks of returning Russia’s ‘natural geopolitical borders’ to include the ‘little Russians’ (i.e. the Ukrainians) and Byelorus. He considers the CPRF to be a party of derzhavniki (great power supporters), of ‘patriots’ who have ‘rejected the extremist theses of class struggle’ to unite the workers with ‘nationally oriented entrepreneurs’. [85] Finally he adds:

It is time for us to recognise that the Russian Orthodox Church is the historical foundation and expression of the ‘Russian idea’ in the form polished by ten centuries of our statehood … The most powerful means of undermining the Russian national consciousness, the main tool for splitting it … are the endless attempts to antagonistically juxtapose in people’s minds the ‘white’ and ‘red’ national ideas … By reuniting the ‘red’ ideal … with the ‘white’ ideal … Russia will at last attain its craved for social, cross-class consensus and imperial might, bequeathed by tens of generations of our ancestors, achieved through the courage and holy suffering of the heroic history of the Fatherland! [86]

From the above it ought to be clear why Zyuganov can happily appear on a platform with Alexander Barkashov. In the autumn of 1994 the CPRF even proposed a new national motto, Slavyas Rossiya! – Glory to Russia! This is identical in meaning and but a slight verbal modification on Barkashov’s version of sieg heil: Slava Rossii! pronounced with outstretched arms by his young Nazi thugs. Zyuganov, however, represents the ‘moderate’ wing of the Communists. Between the CPRF and Barkashov are a number of major organisations laying claim to the Stalinist heritage of the USSR.

First among these is Victor Anpilov and his Russian Communist Workers Party (RCWP). Anpilov is the popular leader of the mass movement Labouring Russia. One of the newspapers claiming to represent the movement – Chto delat? (What Is To Be Done?) – is edited by the Nazi Vladimir Yakushev, leader of the National-Social Union mentioned above, and is full of anti-Semitic filth. Anpilov popularises a brand of ‘Gulag revisionism’ which says that Stalin’s camps weren’t as bad as they are made out to be, and that anyway the end justified the means. According to him, the October revolution swept away the regime that had destroyed the Russian Empire in February. [87] Anpilov is well aware of the history of Stalin’s vicious anti-Semitism, and fully approves:

Stalin saw the danger to the party, bled dry by the bitter war, represented by the remnants of the Zionist Bund that had wormed their way into the Bolsheviks in 1917 and quickly seized the key posts in the party and the state. With typical decisiveness Stalin took practical measures to restore the proletarian character of the party. [88]

The Central Committee of the RCWP includes General Albert Makashov, who led Gorbachev’s crackdown on the Armenian independence movement in Yerevan in 1987–88. In October 1993 Makashov appeared surrounded by Barkashov’s machine gun toting Nazis and led the storming of the Moscow Town Hall.

Another leading figure to advocate ‘national bolshevism’ (the Russian analogue of German national socialism) is Eduard Limonov. [89] After breaking from Zhirinovsky he has made several attempts to unite ‘ultra-communists’ with Nazis, the latest being the launch in November 1994 of the National Bolshevik Party. At a talk at Moscow State University to 250 students in November 1994 he called for a ban on individual freedom, the establishment of a network of informers on every block, the creation of a ‘Führer regime’, and so on.

In June 1994 Limonov united with Barkashov to form the ‘National-Revolutionary Movement’, which has a red flag with a white circle and a black hammer and sickle. [90] (Hitler’s flag was red with a white circle in the middle and a black swastika.) On the pages of Zavtra Limonov and Barkashov made an appeal to ‘Anpilov, red brother’ to join them. [91] Anpilov declined to attend the launch event, but sent his greetings. National bolshevism has attracted some well known supporters. The rock singers Yegor Letov and Pauk (Sergei Troitsky) of the heavy metal groups Grazhdanskaya Oborona and Korroziya Metala are cult figures among Russian youth. Their packed concerts often include the appearance of uniformed Barkashov supporters giving Nazi salutes on stage, and are inevitably accompanied by the sale of Nazi literature.

Hitler and Mussolini also had ‘left wings’ that emphasised the ‘anti-capitalist’ element of this essentially reactionary ideology – in Germany they were associated with leaders of the SA butchered by Hitler during the ‘night of the long knives’, 30 June 1934. This brought the petty bourgeois radicals to heel after they had done the dirty work of smashing the trade unions and the Communists. Daniel Guerin has described at length how Hitler’s Nazis combined their support for capitalism with an anti-capitalist rhetoric:

It was Gregor Strasser who became the brilliant and tireless propagandist of this synthesis: ‘German industry and economy in the hands of international finance capital means the end of all possibility of social liberation; it means the end of all dreams of a socialist Germany … We National Socialist revolutionaries, we ardent socialists, are waging the fight against capitalism and imperialism … German socialism will be possible and lasting only when Germany is freed!’ [92]

Variations on Strasser’s words can be heard at any Red-Brown meeting in Moscow. Limonov makes explicit reference to this side of the ideology of Hitler and Mussolini, and writes: ‘At least Hitler was a revolutionary’. [93] Limonov and Anpilov are the Strasserites of the Nazi movement in Russia today.

The strength of the Russian hard right and its rapid rise to prominence are proof of widespread Russian nationalism in the USSR. But the phenomenon continues to baffle many on the left, who saw in the Soviet Union a buffer against nationalism and a bastion of ‘friendship of peoples’ (to use the hackneyed old Soviet slogan). Thus, in his otherwise useful book on Yeltsin’s Russia, the Guardian’s Jonathan Steele concludes that the emergence of a ‘strong Russian national state’ is an impossibility, and that ‘for the Communists [Russian nationalism] was impossible, given the long tradition of Soviet "internationalism" and the desire to preserve the USSR’. [94] Contrary to such widespread assumptions, however, a central element in Stalin’s counter-revolution was the restoration of Russian nationalism to the status of the dominant and at times official ideology. The Soviet Union was undoubtedly the Russian empire, staffed by Russians inspired by a messianic Russian nationalism, the great majority of them members of the Communist Party.

None of this should come as any surprise to socialists today: [95] in the last years of his life Lenin was well aware that the bureaucratic degeneration of the workers’ state in Russia was opening the floodgates of Russian nationalism. It was precisely on the national question that he first prepared to do battle with the bureaucracy. [96] In 1922 he declared his intention to ‘defend the non-Russians from the onslaught of that really Russian man, the Great-Russian chauvinist, in substance a rascal and a tyrant, such as the typical Russian bureaucrat’. [97]

Already in 1922 Stalin was accusing Lenin of ‘national-liberalism’. ‘They [the bureaucrats] say we need a united apparatus’, Lenin replied, ‘but where did these assurances come from? Did they not come from that same Russian apparatus which we took over from tsarism and only slightly annointed with Soviet oil?’ Lenin was preparing to give battle to ‘the Great-Russian chauvinist riffraff’ at the Twelfth Party Congress in the spring of 1923, but illness prevented him. [98]

Throughout the 1920s Russian nationalist tendencies in the state, literature and art grew in intensity, as Agursky shows in some detail. [99] But a qualitative shift occurred in the first half of the 1930s. According to the émigré sociologist Nikolai Timasheff, this was one of the most striking elements of Stalin’s ‘Great Retreat’ from the original aims of the revolution: ‘in 1934 … the trend suddenly changed, giving place to one of the most conspicuous phases of the Great Retreat, which in the course of a few years transformed Russia into a country with much more fervent nationalism than she ever had before the attempt of international transfiguration’. [100]

As John Dunlop notes in his studies of contemporary Russian nationalism, Russian nationalists today also recognise the significance of the dramatic reversal in official attitudes to Russian nationalism at this time. [101] As the officially sponsored Russian nationalist journal Molodaya Gvardiya put it in 1970:

A nihilistic raging in respect to the cultural achievements of our past was unfortunately rather fashionable among a segment of our intelligentsia in the 20s … Pokrovsky and his ‘school’ placed a fat minus sign before the entire history of Russia … In his [Pokrovsky’s] essays on Russian history (which it would be more correct to term essays on anti-Russian history) the names of [the tsarist generals] Suvorov and Kutuzov are virtually not mentioned … Now it is clear that in the task of the struggle with the destroyers and nihilists the break occurred in the middle of the 30s. [102]

From the mid-30s onwards Russian history reappeared as a sequence of magnificent deeds performed by Russia’s national heroes – the princes of Kiev, the tsars of Moscow, the dignitaries of the church, the generals and admirals of the empire. Symbols of Russian medieval barbarism such as Peter the Great entered the gallery of national heroes. In 1938 Eisenstein’s film Alexander Nevsky, celebrating the life of this medieval prince, was shown on the eve of the anniversary of the revolution. Then came the turn of generals of Catherine the Great and Alexander I: Suvorov was honoured in a film and Kutuzov glorified in a book by the historian Tarle, welcomed back from emigration. Later still came the positive re-evaluation of Prince Bagration, who defeated Napoleon at the battle of Borodino, ‘rehabilitation’ for the leaders of Russia’s First World War campaigns, and in the early 1940s Alexei Tolstoy, the most acclaimed Russian author of the time, was given the honour of writing a play to glorify Ivan the Terrible (Eisenstein’s film was first shown in 1944). The study of Russian history was reintroduced to the school curriculum, creating major problems since there was no patriotic school textbook available. [103]

Russian nationalism reached its apogee during the war. In the words of Alexander Solzhenitsyn, whose political views are on the far right of the spectrum:

From the very first days of the war Stalin refused to rely on the putrid decaying prop of ideology. He wisely discarded it and unfurled instead the old Russian banner – sometimes, indeed, the standards of Orthodoxy – and we conquered! [104]

Glorification of Russian history played a major role in mobilising the war effort. In 1941 anti-religious organisations and publications were closed down and the Orthodox church was rehabilitated. Tsarist uniforms and epaulettes were restored in the army in 1943. Elite military schools were named after Suvorov, Kutuzov and Nakhimov. On 1 January 1944 the Internationale, the USSR’s national anthem since 1918, was replaced by a new nationalist hymn with the opening line, ‘The unbreakable union of free republics has been forged through the Great Rus’. At the end of the war Stalin pronounced his famous toast: ‘To the health of the Russian people!’ [105]

The post-war years until Stalin’s death saw a fearsome nationalist campaign led by Zhdanov, cracking down on ‘rootless cosmopolitanism’ in culture and the arts. Almost all the wars waged by tsarist Russia were proclaimed just and progressive, including the expansionist policies of the pre-revolutionary empire. Classical Russian opera was officially proclaimed ‘the best in the world’, and all Western art from the Impressionists onwards classified as ‘decadent’. Over many years the Soviet press published systematic claims that Russians were leaders in all fields: it wasn’t Edison who invented the electric light, but Lodygin; the Cherepanovs built a steam engine before Stephenson; the telegraph was in use in Russia before Morse in America; Chernov invented steel; even penicillin was announced a Russian discovery. Everything from the bicycle to the aeroplane was declared to be the fruit of Russian talent. [106]

No wonder that today’s Russian nationalists remember the Stalin period with such fondness! For Zyuganov, leader of the Communist Party, given a few more years Stalin could have effected a total reversal to the pre-revolution period:

If its momentum had been maintained, this ‘ideological perestroika’ would have left no doubt that in 10 to 15 years the USSR would have fully overcome the negative spiritual consequences of the revolutionary upheavals … Stalin needed just five or seven more years to make his ‘ideological perestroika’ irreversible and secure the resurrection of the unjustifiably interrupted traditions of Russian spirit and statehood. [107]

The post-Stalin period saw many of these tendencies criticised and somewhat softened under pressure from below, but Russian nationalism remained a key prop of the regime, which continued to direct its ire mainly at the nationalism of the non-Russian republics. The consequences of post-Stalin Russification and national oppression have been described elsewhere in this journal. [108] But in understanding the strength of Russian nationalism today it is important to grasp that Stalin’s legacy in this area was barely scratched, and on the contrary flourished under Khrushchev, Brezhnev and their successors.

Indeed, Russian nationalism was used to combat the democratic ‘excesses’ brought on by the Khrushchev thaw and the Prague Spring. As described in detail by Yanov and Dunlop, the 1960s and 1970s saw a constant tension within the Soviet leadership over the extent to which Russian nationalists should be given a free hand. [109] In the 1960s nationalists ‘were free to an astonishing degree to air their views in the official press’. [110] Nationalists took control of leading journals such as Molodaya Gvardiya, published by the Central Committee of the Komsomol which was but one of the many mass circulation publications to come under nationalist control. Nationalist dissidents received much more lenient treatment than those such as Andrei Sakharov, exiled to Gorky, who criticised the regime from the point of view of Western liberal democracy. [111] The appalling Russian chauvinist and anti-Semitic paintings by Ilya Glazunov, for example, earned him major exhibitions in Moscow and Leningrad in 1978 and one of the finest dachas (country homes) of the Brezhnev period. [112] The strength of the Soviet Writers Union as a bastion of Russian chauvinism under perestroika is an indication of the extent to which nationalist writers were encouraged – their books were produced in print runs of hundreds of thousands (many figures in the Soviet Writers Union are now leading Nazi ideologists, such as Prokhanov and Bondarenko). Throughout the 1970s these and other writers made increasing attempts to weld a common ideology integrating the Communist period into the credo of the nationalist right. When Alexander Yakovlev, head of the Central Committee’s propaganda department, came out with criticism of brute Russian nationalism in the early 1970s he was swiftly demoted and packed off to Canada as a diplomat. [113]

Surveying this history back in 1986, Yanov concluded that the maintainance of a strong ‘dissident right’ in the Soviet Union was a conscious decision by the leadership to retain a fallback option to the establishment ideology. The official ‘Communist’ right understood that the growing crisis of the Soviet system demanded counter-reform. According to this logic:

reform demands a radical change in ideology capable of restoring the empire’s former mobilisational character, securing the active co-operation and support of the masses and parts of the intelligentsia, and of justifying a sharp increase in production, family and cultural discipline and a resurrection of a fighting expansionist dynamic. Orthodox Marxism is no longer capable of such a shift. It cannot justify a return to the ideological atmosphere of war communism [1918–21] … In other words, counter-reform demands an ideological strategy, for the development of which the ‘establishment right’ has no intellectual or moral resources apart from those that inspire its hounded and persecuted dissident sister. In this sense it is certainly intellectually ‘vulnerable’ to the more precise dissident nationalists. [114]

It would be wrong, however, to see Russian nationalism as merely a bureaucratic conspiracy to keep the masses down. Russian nationalism was deeply ingrained in the Soviet Russian population, just as in any other capitalist nation state under normal conditions. By its very nature, the totalitarian dictatorship precluded detailed sociological research, attitude surveys and so on. But there are certain useful indicators of the strength of Russian nationalism in the population, such as letters to the samizdat (unofficial) journal Veche, the mass membership of organisations involved in restoring national monuments, and of course the stunning popularity of artists such as Glazunov. [115] In a society in which workers have been defeated, atomised, their organisations crushed, we would expect nationalist ideas to find a fertile ground.

If Stalin was prepared to use Russian nationalism to cement a social base for his regime, he certainly had no scruples about restoring anti-Semitism to official status. Though the revolution had staunched the wounds of anti-Jewish feeling in the population, enabling Jews such as Trotsky, Zinoviev and Sverdlov to become national figures, the revolution’s defeat saw the gangrene grip the patient harder than ever. When Shulgin, the tsarist politician whose anti-Semitic tirades plumb the very depths, made a secret visit to Russia in 1926, he was delighted to find widespread anti-Semitism:

I thought I was going to a dead country, but I saw the awakening of a great country … The Communists will give power to the fascists … [Russia] has eliminated the dreadful socialist rubbish in the course of just a few years. Of course, they’ll soon liquidate the Yids. [116]

Stalin’s war on Trotsky and the Left Opposition was carried out under the banner of anti-Semitism. As Trotsky later wrote:

After Zinoviev and Kamenev came over to the opposition the situation rapidly worsened. Now there was an excellent opportunity to tell the workers that the opposition is led by ‘three disgruntled Jewish intellectuals’. At Stalin’s command Uglanov in Moscow and Kirov in Leningrad followed this line systematically and almost completely openly … Not only in the countryside but even in Moscow factories baiting of the opposition by 1926 often took an absolutely clear anti-Semitic character. Many agitators openly said: ‘The Yids are playing up’. I received hundreds of letters complaining about anti-Semitic methods in the struggle against the Opposition. [117]

From Germany Hitler’s companions Ribbentrop, Strasser and Goebels observed this process with glee – Strasser was convinced that Stalin’s aim was to stop the revolution and liquidate communism. [118]

The purges of the mid-1930s meant a further turn for the worse, with organised Jewish life almost completely paralysed: Jewish schools were closed in their hundreds along with Jewish newspapers and departments of Yiddish language and culture. During the years of the Nazi-Soviet pact (1939–41) the Soviet press ceased to report on Nazi persecution of the Jews and the murder of Jews in Poland after war broke out. [119]