Main ISR Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

International Socialist Review, Summer 1960

Bert Deck

Challenge of the Negro Student

From International Socialist Review, Vol.21 No.3, Summer 1960, pp.70-73.

Transcription & mark-up by Einde O’Callaghan for ETOL.

|

New leaders are now coming to the fore in the Southern Negro movement and are questioning all the doctrines of the past

|

* * *

AN ESTIMATED 100,000 Southern Negro students have participated in mass demonstrations against segregation since McNeil A. Joseph, 17, and three classmates “sat-in” at a Woolworth store in Greensboro, North Carolina on Feb. 1, 1960 and ordered coffee.

These unprecedented actions on the part of the students caught friend and foe, alike, off guard. The apathy of the American students has long been the subject of complaints by shamefaced professors who had knuckled down to the cold-war witchhunt of the fifties. Conformism and narrow self-interest seemed to be a permanent feature of campus life. The “frat” boys ruled supreme and the generations were either beat or beaten.

Even more confounding was that the original source of the movement was the Southern Negro universities which had developed the reputation of being even more middle class, more apathetic and more conservative than the general run of deadening American universities.

Yet seemingly out of nowhere a “spontaneous” movement erupted and wise heads conjured with it and noted the apparent relationship with the action of the students in Korea, in Japan, in Turkey, in Cuba.

“An older generation was passing,” commented the liberal Nation. “The objective had to be more than to endure an hour and see injustice done.”

Mass uprisings and revolutions are considered commonplace for the Far East, and the Middle East. But “All Quiet on the Western Front” was to be the epitaph over our tradition of rebelliousness which was thought to be buried forever. However, a new generation has announced itself and proclaims that nothing is going to be the same again.

* * *

The new Southern Negro movement is understood by all to be a student movement. The adults and their organizations enter as supporters of the actions. Student organizations for social or educational purposes are readily understandable. But how explain an independent student movement on a social question which affects, not only the students, but the entire population?

“... the movement is a protest not only against segregation,” writes Dan Wakefield in the May 7 Nation, “but against the older Negro leaders ... The sit-ins have brought the students’ feeling of protest over the adults’ ‘slow’ tactics into the open.”

Martin Luther King, Jr., at a Raleigh, North Carolina conference of student leaders on April 15, described the student movement as “... a revolt against the apathy and complacency of adults in the Negro community; against Negroes in the middle class who indulge in buying cars and homes instead of taking on the great cause that will really solve their problems; against those who have become so afraid they have yielded to the system.”

In other words the existence of independent student organizations is a de facto criticism by the youth of policies followed by the old established organizations. Their situation as students gives them a formal basis for separate organization and they have taken advantage of it.

THE deep gulf between the new generation and the conservative NAACP leadership is well understood by all commentators. What is not yet fully appreciated is that the students are likewise separating themselves from the leadership of the radical pacifists such as Reverend King and The Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Wakefield, an unqualified supporter of King, writes, “The students now have their own organization, which will work with, but not be led by adult groups such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, CORE (Congress on Racial Equality) and the NAACP, as well as local church and civic groups.” (Our emphasis.)

As the leaders of the King generation (late twenties and early thirties) rose to challenge the narrow policies of the NAACP a few years ago, so now an even younger group of leaders is taking shape and probing deeper into the fight for full integration.

The last previous high point of the Negro struggle was reached by the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955-56. It taught that the power of mass action was superior to individual resistance or the strictly courtroom road to integration. The students learned from the Montgomery experience that bold moves could inspire and win the support of the community as a whole. Indeed, an inspiring victory was won when the courts went even further than the original demands of the Negroes. They desegregated the busses altogether which was more than the boycotters had hoped for at first.

In spite of this victory won by the mass action and confirmed by the courts, the old pattern has since largely reasserted itself. Seating from rear to front by the Negroes is once more the rule on Montgomery busses. How could this have happened?

By their courage and unity in action the Negroes forced a concession from the racists. But the latter, through the Democratic party, hold state power and wield it as a bludgeon against the mass movement. Any victory of the integration movement is immediately challenged by this machine. What it is forced to give with one hand, it seeks to take back with the other. Every victory has a question mark placed over it. It becomes partial, transitional and in the last analysis, subject to the test of further struggle. This will be the case as long as the racists are permitted to remain entrenched in the very seat of economic and political power in the South.

The danger of a setback in Montgomery was implicit in the partial character of the victory and would have been present even under the best of leadership. However, the inadequate ideology of pacifism, which refuses to recognize the existence of irreconcilable social forces, undoubtedly contributed to the weakening of the mass movement.

THE Montgomery movement threw up a group of new leaders among the younger ministers led by King. These ministers joined with their counterparts throughout the South to form the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. There is no doubt that the more militant section of the Negro movement looked hopefully at first to this new organization to spark mass actions on a South-wide basis. However, the Conference proved unable to fulfill this hope and the initiative for the next round of mass actions came from a new source: the students.

An unmistakeable quality of this new generation of Negro fighters is their unconditioned demand for full equality. They are in favor of immediate and total abolition of all forms of discrimination. They have no other interests or causes which conflict with this program. In fact any social cause standing opposed to total and immediate desegregation is for them unsupportable and evil – by definition. If any political, economic, social institution or any philosophy stands in the way – then let it go down! These students apparently have sensed that a number of their aspiring adult leaders have “divided” loyalties; thus, their independence.

Montgomery has shown that before the liberation movement can be assured an irreversible and total victory it must become a political power itself dedicated to establishing a government committed to full integration; a government which by its composition, its social base and stated program will be capable of enforcing Negro rights.

To speak now of a “new” type of political power in the South may seem far-fetched; a rushing of the season, at any rate. But a new generation is now preparing itself for the long march to full victory and it is necessary to understand their struggle in perspective.

At the present time the liberation movement is a minority. How can one realistically propose its becoming the political power? The question assumes that all things will remain the same in a world where nothing remains the same. If the present relationship of forces were to freeze then the cause of integration would be a hopeless one. There is no historic precedent of a minority defeating a hostile and organized majority. The struggle, itself, presupposes that the relationship of forces will change.

The strategy for victory then resolves itself into ways and means of splitting the majority; winning over one section, neutralizing another, and reducing the hard core racists to an impotent minority.

* * *

The pacifists have a proposal for winning a majority. Dave Dellinger, an editor of the pacifist monthly Liberation, describes the strategy of pacifism as follows.

“When non-violence works, as it sometimes does against seemingly hopeless odds, it succeeds by disarming its opponents. It does this through intensive application of the insight that our worst enemy is actually a friend in disguise. The non-violent register identifies so closely with his problems as if they were his own and is therefore unable to hate or hurt him, even in self-defence.”

James Bristol writes a Primer for Pacifists:

“There is tremendous power in love, non-violence and good will both to change people and to alter social situations. This follows naturally from our first conviction that people can be appealed to by love, no matter how brutal they may be ...”

Pacifism holds that all men, regardless of their material interests, can be won through love. It denies that social relations can place men in positions of irreconcilable opposition to each other.

For the pacifist, then, the integration movement will triumph when a majority is convinced of the moral superiority of the minority.

There is another aspect of the modern pacifist movement, at least one wing of it, which requires further comment. That is the attempt of such individuals as Martin Luther King and Bayard Rustin to incorporate within the basic strategy of pacifism the techniques of mass action (strikes, sit-downs, boycotts, etc.) which were first developed, not by the pacifists, but by the labor movement.

The techniques of mass action tend to run counter to the basic philosophy of pacifism. On the face of it, mass actions are not the exertion of love on the enemy. They are effective in so far as they exert the force of numbers in the defense of a rightful cause.

KING is vaguely aware of this contradiction. At the Raleigh conference he expressed his fear that the students would draw other than pacifist conclusions from their experience in the sit-in movement. He warned:

“Resistance and non-violence are not in themselves good. There is another element in our struggle that then makes our resistance and nonviolence truly meaningful. That element is reconciliation. Our ultimate end must be the creation of the beloved community. The tactics of nonviolence without the spirit of nonviolence may become a new kind of violence.”

It is the acceptance of the legitimacy of mass action by some pacifists that makes possible limited united actions with the Marxists such as occurred in the Northern student supporting movement, i.e., the picketing of Woolworths and other Jim Crow chains.

While the Marxists can cooperate with the pacifists in specific mass actions they are careful to point out that the “spirit” of pacifism endangers the effectiveness of mass techniques. The “spirit” of pacifism directs the mass movement toward the undefined conscience of the opponent and thus misdirects the fire of the action. The Marxists, on the other hand propose that the mass actions be directed at the material interests of the enemy in order to destroy the basis of his power. The Montgomery bus boycott and the current sit-ins have this in common; they both affect the economic condition of the oppressors.

* * *

The Marxists approach the problem of winning a majority to the integration movement in a completely different fashion from the pacifists.

Their analysis of history, Negro history included, discloses that every social movement has at its base the material interests of the classes it represents. They discovered that behind every struggle between “justice” and “injustice” lies the social and economic positions of the combatants, which determine their conceptions of these terms. They conclude, therefore, that the majority of whites in the South will see that “justice” is on the side of the Negro when they first see that their own interests can be served by the victory of the Negro. Is such a situation possible?

Despite its ominous outward appearance the Solid South is torn with internal fissures.

Harrison Salisbury writes in the April 15 New York Times:

“Under the erosive impact of the segregation issue, Alabama’s political and social structure appears to be developing symptoms of disintegration ... Even if Alabama had the political will to achieve positive solutions of its problems it would be badly handicapped by existing disenfranchisement which affects whites almost as much as Negroes ... the Black Belt counties (i.e. the tiny minority of white merchants and landowners who rule the predominantly Negro counties – B.D.) would not be able to maintain their stranglehold on state government and their retrograde influence on state policy were it not for a powerful ally, the big industry of Birmingham. The biggest of Birmingham’s so-called “big mules” is US Steel, whose subsidiary Tennessee Coal and Iron, dominates the city economically and, to a considerable extent, politically.

“The ‘big mules’ and the Black Belt cooperate and, together, usually run the state ...”

Salisbury, who is no Marxist, nevertheless sees the fracturing of the white community along class lines. He observes that the present rulers of the South are not the white community as such but only a small section of it: the Northern industrialists and their Southern counterparts in alliance with the county merchants and landowners.

The segregation system is indispensable to the rule of this capitalist coalition. Not only does segregation keep the general wage level of the South depressed, but it inhibits the potentially anti-capitalist sentiments of the majority by directing all animosity toward the Negroes. Race prejudice has been the traditional cement used by the Southern rulers to patch up their class-torn white society.

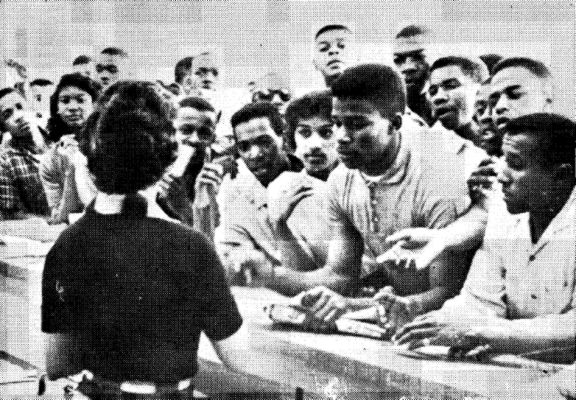

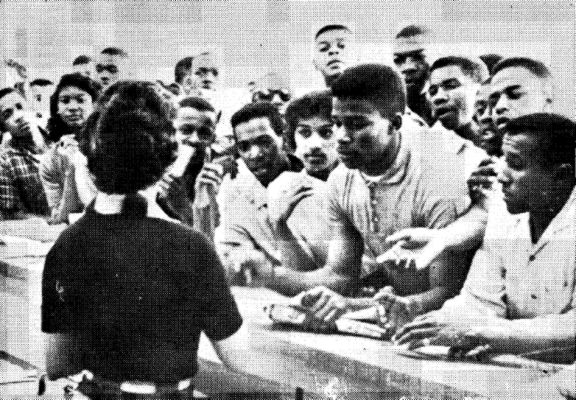

Hundreds of students at Southern University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, lined up at registrar’s office to ask for forms to withdraw from the school in protest over the expulsion of sixteen of their classmates, who were victimized for conducting lunch-counter sit-ins on March 30.

Prior to their expulsion, the sixteen were jailed. This led to a protest demonstration on the steps of the state capitol by 5,000 Southern University students.

When the sit-in students were suspended the withdrawal movement began.

|

FOR the majority of Southern whites are not industrialists, landowners and merchants; but rather workers and poor farmers. They are economically exploited and politically disenfranchised by the ruling class. Their only hope is to form an alliance with the Negro masses, with whom they would constitute an overwhelming majority, and thus could become the political power in the South.

Such, at any rate, has been the general Marxist forecast: that the Negro minority could solve its social problem because the white majority would divide along economic lines, opening up the possibility for a majority coalition which could serve the material interests of both the Negroes and the oppressed whites.

This will be no easy road; in fact, no easy road exists. The Negroes are fully aware of the deep hostility directed toward them from the oppressed white community. The color line barrier seems as unbreachable as it is irrational.

Yet, there is an historical precedent for just such a breach. Southern workers in the thirties, who had emigrated to the North, became so imbued with the idea of industrial unionism that they were prepared to suppress their deeply ingrained prejudice against their Negro fellow workers. They needed the cooperation of the Negroes to get what they wanted. Without that cooperation, they could not have built the unions.

The ex-Southern worker of the thirties, who had previously followed the lead of the extreme racists, found himself in a new social situation with the coming of the CIO. The Negro was supporting the white worker’s right to form a union. A number of the white workers passed out of the control of the racists while others became outspoken supporters of full equality. The white and Negro workers formed an alliance against a common enemy and the interests of both groups were thereby served.

There is no reason to doubt that a changing social situation in the South today will not effect similar shifts. The Negro youth are already on the march. They are not waiting for the white workers, nor does wisdom dictate that they should. Salisbury has observed that the Negro struggle has gone a long way to break down the cohesiveness of traditional Southern society. The Negro action in its own name for its own cause has already had serious effects inside the white community.

Every success of the students will embolden the entire Negro community, especially the workers. As the movement increases in power it can speak to the oppressed whites with the voice of authority. The age-old cries for “justice” and “morality” too often fell on deaf ears. But as an organized power the Negroes will have a new appeal for the white workers and poor farmers; for they will be in a position to offer the latter real help in their own struggles.

There is a very real possibility that the Negro movement will become the leading spokesman for the interests of all the Southern oppressed.

This much, at any rate, can be said at present. The Negroes, especially the students, have taken the first initiative. Also by organizing independently, the Negro students have taken upon themselves the responsibility to formulate a new program. The stage is being set for an even broader attack on the racist industrialists, landlords and merchants.

THE new crusade (as the students term it) will find that it must remove the number one political obstacle on the path to victory: the Democratic party machine.

This is the muscled arm of the ruling class. It staffs the local and state apparatuses; the police and sheriff’s departments, the courts, the mayors’ offices. It sets the policies for all public educational institutions through patronage and political appointments.

It is the open avowed policy of the Democratic party to hold the line against integration. In fact it is the broadest, most effective weapon in the hands of the racists. It is the anti-civil rights movement. The KKK and the White Citizen Councils are mere factions of it. “Legal” equality for the Negro in the South would be little more than a farce as long as this venal machine retains its grip on Southern society. The logic of the integration movement means the smashing of this machine and its replacement by one independent of the capitalist rulers: a coalition of all the oppressed, Negro and white, with the Negroes playing a decisive role.

But if the Southern wing of the Democratic party is smashed by the integration movement what happens to it nationally? The Southern wing is necessary to the party for its survival as a national force. Even a united party is threatened with a decline at present. A divided party would signal the end altogether.

This would mean the end of the most effective tool in the hands of the capitalists to forestall the independent political organization of the labor movement, the Negro people and the small farmer. The most likely outcome of the disintegration of the Democratic party would be the formation of a Labor party which would challenge the capitalist structure of the North as well as the South.

This inescapable logic of the Negro rights movement is what gives pause to many of the present spokesmen of that movement. They are hoping against hope that a way can be found to circumvent necessity. Not class struggle but “reconciliation.” They seek to temper the struggle long enough so that they may carry out their vain search for the non-existent path to Negro equality which leaves undisturbed all the other abominations of capitalist society. For in their heart of hearts they would prefer a capitalist Jim Crow society to the struggle for a non-capitalist one of human equality.

Top of page

Main ISR Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

Last updated on: 5 May 2009