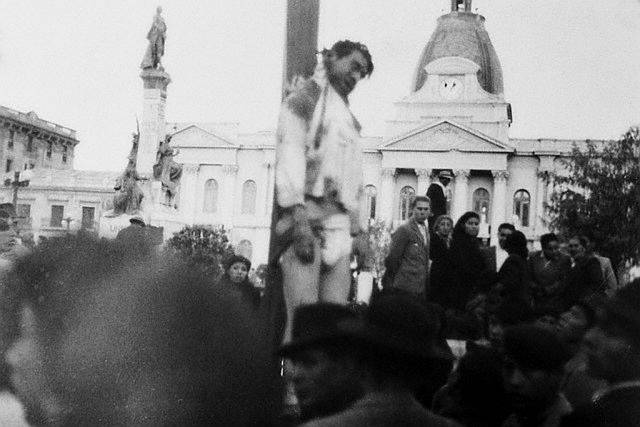

Dictator Villaroel handing from a lamp post in front of his church [1]

Main LA Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

From Labor Action, Vol. 10 No. 34, 26 August 1946, p. 3.

Translated by Mary Bell.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for ETOL.

LA PAZ, Bolivia. – The fall of the totalitarian regime of Villaroel in Bolivia surprised the entire American continent, just as the revolution surprised the Bolivians themselves. The fallen regime had emerged from a political and social crisis provoked by the Bolivian defeat in the Paraguayan-Bolivian war.

The republic of Bolivia has an economy in which the exploitation of the mines plays the decisive role, the export of minerals, in the first place, of tin, constitutes the basis of the budget and the national commerce. In spite of its economic backwardness, the national wealth and the means of production are concentrated in the hands of a few capitalists, Patinorey, M. Hochschild and C.V. Aramayo; these men decide practically on the mineral production of the country, treating it as their special hacienda. Dependent upon the world markets and Anglo-American imperialism, they exploit the masses, kept in a state of barbarous poverty, in the interests of their own and foreign imperialism.

The traditional Bolivian parties (Republican, Republican-Socialist, Liberal and “Socialists”) are political organizations only in the interests of the Bolivian feudo-capitalists. The economic and social structure is semi-feudal and semi-colonial, the indigenous masses constituting an element despoiled by the feudal, latifundist aristocracy – without a stake in the nation. The traditional “democratic” political structure controlled by the feudo-capitalists suffered a collapse in the Chaco war and the army placed itself at the head of the government of the country (dictatorship of Toro and Busch). The attempt to reconstruct the traditional government of the right – known in Bolivia as “Rosea,” and embodied in the constitutional regime of General Penaranda – was shattered by the economic and social problems of the country.

The Chaco war stirred the working masses against the feudo-capitalists and thus undermined the traditional Bolivian political structure. Under the pressure of imperialism, especially the American variety, the price of tin dropped, with the whole burden falling on the shoulders of the mine workers. The miners of Bolivia work at an altitude of 4,000–5,000 meters for miserable salaries, and food gotten from company stores. They live in cold huts scarcely covered with straw and are weakened in a few years to die of lung disease. Thus bleeds and dies the Indian race, the trunk and the root of Bolivian nationality, in the interests of imperialism. Socialist writers call this the tragedy of the “Altiplano” (high plateau).

The low prices of tin and rubber undermined the foundations of the Penaranda government. From the recently sprouted middle and mestizo (white and native offspring) class and from the official caste of the military, spurted a nationalist reaction, carefully prepared by the Germans. In the year 1943 this class made a coup d’etat by taking advantage of discontent against the government stemming from the massacre of the miners in Catavi.

The new regime leaned on two forces, the nationalist revolutionary movement led by V. Paz Estenssoro, ex-Stalinist, and the military lodge, “Santa Cruz,” headed by the mayor, Elias Belmonte, a faithful disciple of the Nazi military instructors in Bolivia. Deftly using the leftist and national anti-imperialist phraseology, the regime succeeded in maintaining itself for three years, suppressing in blood all the blows directed against the state from the right.

But it could not dominate a popular revolution which broke out in the month of July 1946. The fall of Hitler, who was the patron of the creole Nazis, the post-war crisis and the offensive of the masses against totalitarianism undermined the basis of the Villaroel-Paz Estenssoro regime. The system of terror, of oppression of the liberal and proletarian opposition, of elimination of the opposition press, inflamed the entire people. The mestizo class, heretofore the mainstay of the government, became disillusioned with Nazism and evolved in the direction of creole Stalinism, expressed in the PIR (Party of the Revolutionary Left) led by Jose Antono Arze, agent and functionary of Stalin. The government could defeat all the coups d’etat, so traditional in the South American states, but it could not defeat the people and their opposition.

After a suppressed palace-military revolution in June, several workers’ strikes broke out in railroad, transportation, and engraving which the government was accustomed to solve with great facility. But the strikes were not purely economic. They expressed, rather, the discontent of the working class with the government.

The strike of the newspapers and engravers was directed against confinements and arrests and the gagging of the press. The strike of the teachers, aside from its economic character – the Bolivian teacher earns much less than the worker – had also a political character: against the totalitarian politics of the government, against the provocative comforts of the military. The strike of the teachers was supported by the university students and those of the secondary schools and produced some youthful demonstrations which were shot down by the government. Then the teachers and students asked the workers’ unions for help in the form of a general strike. The unions, with some hesitation, declared a stoppage; nobody thought that this would produce a political revolution.

But the situation was pregnant with revolution. The general strike paralyzed the life of the nation completely, stopping not only factories and communications but all commerce and public offices. The people were by no means set for a revolutionary political action. The youth demonstrations, brutally fired on by the government, played the role of a match applied to a powder key. The students, enraged by the brutality of the police, made up flying squadrons of revolutionary agitation, instigating women, workers and the people in general to demonstrate their opposition against the government of “assassins.” Day after day demonstrations took place in various districts, reassembling in the main square in spite of the sharp-shooting. On Friday, July 19, 1946, the enormous demonstration of 20,000 persons, shot at by cross fire, could not retreat in the narrow streets and took the square. The government lost its courage, had to stop the shooting and retreated.

On the following day the assassin government had to abdicate and a purely military cabinet was formed. But it was already too late. The people clamored: “We want a civil government!” Sunday the demonstrators took over the municipal seat, finding arms with which they attacked the traffic and prison police. Within a few hours the palace of the government fell and president Villaroel hung from a lamp post across from his church. (See photograph.)

Dictator Villaroel handing from a lamp post in front of his church [1] |

This Bolivian revolution was not a traditional coup of the military, but was a popular movement. Its political character was bourgeois-democratic, understandable in the midst of the semi-feudal economy in Bolivia where the democratic revolution is on the order of the day. Nevertheless, it would be false to underestimate the role of the working class. The workers’ strikes had a decisive character in the development of the revolution and constituted its principal form. The first workers’ strikes were a prelude of the movement and the repetition of the strikes formed the spine of the revolution. Only on the basis of a general stoppage were the small student demonstrations able to transform themselves into powerful popular demonstrations of a revolutionary character with a final popular assault on the government.

The Bolivian proletariat does not understand its decisive political role in the last revolution. The Stalinists of the PIR do everything to kill the social and political consciousness of the Bolivian workers, posing the slogan of a democratic anti-fascist front against the proletarian united front; that is, the subordination of the proletariat to the Bolivian feudo-bourgeoisie, against the independent action of the working class. The Bolivian anti-fascist front played no role in the revolution itself. Its blows against the state were moderated; it neither knew how or wished to unleash the action of the masses. Therefore the union movement spontaneously became a decisive factor of the revolution, but without a program or political consciousness.

The workers’ parties, the PSOB (Bolivian Workers Socialist Party) of Maroff and the POR (official Trotskyists) were caught with their pants down. It is true that in the assault on the palace and in the first hours of the revolutionary triumph, the elements of both organizations played an important role but as individuals, and not as representatives of organizations. In face of the spontaneity of the workers’ movement, after the revolutionary triumph this role has been taken away from them by the middle-class and capitalist elements. One of the leaders of the PSOB said that “the revolution died when the regime was demolished, at the doors of the seat of government.” If this was so, it is the fault of the workers’ parties, The distinction between the ideology and the social content of the revolution is of utmost importance in appreciating the political and social status of the South American countries.

The capitalist parties were also surprised by the revolution. For this reason the people did not hand over power to any political coalition. Moreover the slogan, “We do not want a return to politics as usual,” prevented this. Several hours elapsed until representative bodies of students, teachers and workers were set up to elect delegates to form a new “non-political” government assembly, headed by the supreme court of the district, whose magistrates won their prestige by their opposition to the abuses of the government.

When it handed over power to the judicial magistrates, the popular-democratic revolution died, since it could not be transformed into a democratic revolution under the leadership of the working class parties and the unions, in spite of the decisive role of the Bolivian proletariat.

The political “independence” of the government assembly, which formally does not depend on the political parties, favors the penetration of the rightists to power, a penetration the people wish to avoid. The “fuehrer” of the Stalinist PIR, Arze, on returning from Chile, tried to appropriate for the committee of the “anti-fascist front” the decisive role in the preparation of the revolution. This organization is a coalition of the rightists with the PIR (Stalinist). But the danger for the democratic revolution comes not only from the right parties. Military and civil nazism withdrew from power, with its money, arms and organizations intact. The assembly did not undertake a general purge against Bolivian nazism which menaces not only the assembly itself, but the democratic revolution.

The Bolivian working class, after accomplishing the assault on the palace, retired from the scene and dissolved the workers’ militias. Thus, the spontaneous revolutionary action did not have either political or social consequences.

We understand thoroughly that in Bolivia and other South American countries the bourgeois-democratic revolution and not the socialist revolution is the order of the day. But the experience of “Altoplano” shows us that there is no revolution possible without the decisive role of the proletariat. To establish political democracy, to win the social rights of the proletariat, the conscious understanding of the parties is necessary. A spontaneous action of the unions is not enough.

The Bolivian revolution points out to us the great possibilities for the Marxist parties in South America and also reveals the great poverty of political development of the South American proletariat, which plays the part of a “Sancho Panza” to the middle class.

1. This is not the original photo published in Labor Action, but another slightly higher quality one taken from a similar angle. The photo printed hin Labor Action can be found here.

Main LA Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

Last updated on 8 July 2019