![]()

Write us!

socialistviewpoint@pacbell.net

July/August 2004 • Vol 4, No. 7 •

Confused? Shadow of His Old Self? Hardly

By Robert Fisk

|

|

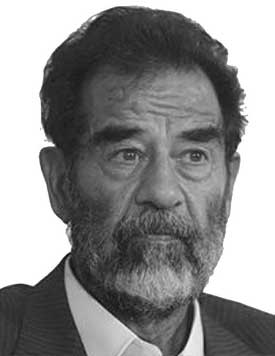

Saddam Hussein

|

Bags beneath his eyes, beard greying, finger—jabbing with anger, Saddam was still the same fox, alert, cynical, defiant, abusive, proud. Yet history must record that the new “independent” government in Baghdad yesterday gave Saddam Hussein an initial trial hearing that was worthy of the brutal old dictator.

He was brought to court in chains and handcuffs. The judge insisted that his own name should be kept secret. The names of the other judges were kept secret. The location of the court was kept secret. There was no defense counsel. For hours, the Iraqi judges managed to censor Saddam’s evidence from the soundtrack of the videotaped proceedings—so that the world should not hear the wretched man’s defense. Even CNN was forced to admit that it had been given tapes of the hearing “under very controlled circumstances.”

This was the first example of “new” Iraq’s justice system at work—yet the tapes of the court appeared on CNN with the logo “Cleared by U.S. Military.” So what did the Iraqis and their American mentors want to hide? The voice of the Beast of Baghdad as he turned—much to the young judge’s surprise—on the court itself, pointing out the investigating lawyer had no right to speak “on behalf of the so-called coalition”? Saddam’s arrogant refusal to take human responsibility for the 1990 invasion of Kuwait? Or his dismissive, chilling response to the mass gassings of Halabja?

“I have heard of Halabja,” he said, as if he had read about it in a newspaper article. Later, he said just that: “I’ve heard about them [the killings] through the media.” Perhaps the Americans and the Iraqis they have appointed to run the country were taken by surprise. Saddam, we were all told over the past few days, was “disorientated,” “downcast,” “confused,” a “shadow of his former self” and other clichés.

These were the very words used to describe him on the American networks from Baghdad yesterday. But the moment the mute videotape began to air, a silent movie in color, the old combative Saddam was evidently still alive. He insisted the Americans were promoting his trial, not the Iraqis. His face became flushed and he showed visible contempt towards the judge. “This is all a theatre,” he shouted. “The real criminal is Bush.”

The brown eyes moved steadily around the tiny courtroom, from the judge in his black, gold-trimmed robes to the policeman with the giant paunch—we were never shown his face—with the acronym of the Iraqi Correctional Service on his uniform. “I will sign nothing—nothing until I have spoken to a lawyer,” Saddam announced—correctly, in the eyes of several Iraqi lawyers who watched his performance on television.

Scornful he was, defeated he was not. And of course, watching that face yesterday, one had to ask oneself how much Saddam had reflected on the very real crimes with which he was charged: Halabja, Kuwait, the suppression of the Shia Muslim and Kurdish uprisings in 1991, the tortures and mass killings. One looked into those big, tired, moist eyes and wondered if he understood pain and grief and sin in the way we mere mortals think we do. And then he talked and we needed to hear what he said and the question slid away; perhaps that is why he was censored.

We were supposed to stare at his eyes, not listen to his words. Milosevic-like, he fought his corner. He demanded to be introduced to the judge. “I am an investigative judge,” the young lawyer told him without giving his name. In fact, he was Ra’id Juhi, a 33-year old Shia Muslim who had been a judge for 10 years under Saddam’s own regime, a point he did concede to Saddam later in the hearing without telling the world what it was like to be a judge under the dictator. He was also the same judge who accused the Shia prelate Muqtada Sadr of murder last April, an event that led to a military battle between Sadr’s militiamen and U.S. troops in the holy cities of Najaf and Kerbala.

Mr. Juhi, who most recently worked as a translator, was appointed—to no one’s surprise—by the former U.S. proconsul in Iraq, Paul Bremer. Already, one suspected, Saddam had sniffed out what this court represented for him: the United States. “I am Saddam Hussein, the president of Iraq,” he announced—which is exactly what he did when U.S. Special Forces troops dragged him from his hole on the banks of the Tigris river seven months ago. “Would you identify yourself?”

When Judge Juhi said he represented the coalition, Saddam admonished him. Iraqis should judge Iraqis but not on behalf of foreign powers, he snapped. “Remember you’re a judge, don’t talk for the occupiers.” Then he turned lawyer himself. “Were these laws of which I am accused written under Saddam Hussein?” Judge Juhi conceded that they were. “So what entitles you to use them against the president who signed them?” Here was the old arrogance that we were familiar with, the president, the rais who believed he was immune from his own laws, that he was above the law, outside the law. Those big black eyebrows that used to twitch whenever he was angry, began to move threateningly, arching up and down like little drawbridges above his eyes.

|

|

Saddam Hussein brought to court in chains

|

The invasion of Kuwait was not an invasion, he said. “It was not an occupation.” Kuwait had tried to strangle Iraq economically, “to dishonor Iraqi women who would go into the street and would be exploited for 10 dinars.” Given the number of women dishonored in Saddam’s torture chambers, these words carried their own unique and terrible isolation. He called the Kuwaitis “dogs,” a description the Iraqi authorities censored to “animals” on the tape. Dogs are, alas, one of the most cursed of creatures in the Arab world.

“The president of Iraq and the head of the Iraqi armed forces went to Kuwait in an official manner,” Saddam blustered. But then, watching that face with its expressive mouth and bright white crooked teeth, the eyes glimmering, a dreadful thought occurred. Could it be this awful man—albeit given less chance to be heard than the Nazis at the first Nuremberg hearings—actually knew less than we thought? Could it be that his apparatchiks and groveling generals, even his own sons, kept from this man the iniquities of his regime? Might it just be possible that the price of power was ignorance, the cost of guilt a mere suggestion here and there that the laws of Iraq—so immutable according to Saddam—were not adhered to as fairly as they might have been?

No, I think not. I remember how, a decade and a half ago, Saddam asked a group of Kurds whether he should hang “the spy,” Farzad Bazoft, and how, once the crowd had obligingly told him to execute the young freelance reporter from The Observer, he ordered his hanging. No, I think Saddam knew. I think he regarded brutality as strength, cruelty as justice, pain as mere hardship, death as something endured by others.

Of course, there was that smart, curious black jacket, more a sports blazer than a piece of formal attire, the crisply cleaned shirt, the cheap pen and the piece of folded, yellow exercise paper which he took from his jacket pocket when he wanted to take notes.

“I respect the will of the people,” he said at one stage. “This is not a court—it is an investigation.” The key moment came at that point. Saddam said the court was illegal because the Anglo-American war, which brought it into being, was illegal—it had no backing from the UN Security Council. Then Saddam crouched slightly and said with controlled irony: “Am I not supposed to meet with lawyers? Just for 10 minutes?” And one had to have a heart of stone not to remember how many of his victims must have begged, in just the same way, for just 10 more minutes.

—The Independent (UK), July 2, 2004

Write us

socialistviewpoint@pacbell.net