![]()

Write us!

socialistviewpoint@pacbell.net

Palestine: From Statelet to Protectorate

By Yacov Ben Efrat

Part Two:

A Dearth of Self-Criticism, an Intifada with neither program nor leadership

During the Intifada, Israeli attacks were carefully planned. Their objectives suited the regional balance of forces. This cannot be said for the Palestinian side. The PA has been confused and divided. The major Palestinian movements (Fatah and the Islamic groups) have acted each according to its own program. While Israel always took account of international developments and the reactions of the Arab world, careful to keep its military operations from escalating into total war, the Palestinian side shrank into itself, ignoring what went on outside.

From the moment the Intifada erupted, the PA shrugged off responsibility. It was the sole recognized authority in its areas, and yet its security forces looked on helplessly as Palestinian youth at the checkpoints, armed with stones, fell before Israeli fire. As we said in Part One, the PA found itself in a complex and embarrassing dilemma: On the one hand, it could not stop the Intifada—and hoped, in fact, that it would bring political gains. On the other, it couldn’t openly join the fight because of its commitment to the Oslo Accords, which forbid taking arms against Israel. As a result of this predicament, it lost face both with its people and with its Oslo patrons.

Fatah is the largest Palestinian organization and the only one whose leaders belong to the PA. Arafat, to the present day, heads both the PA and Fatah. Yet in relation to the Intifada, Fatah chose to behave in a manner diametrically opposed to the PA. Given its military operations against Israel, a line developed—at least for public consumption—separating Arafat from Marwan Barghouti, head of Fatah’s military wing, the Tanzim. Here was a strange kind of co-existence, between a government that condemned armed operations and an organization, financed by it, which carried them out. Fatah members explained this dichotomy as follows: We are not committed to the same agreements that the PA signed at a time of weakness.

|

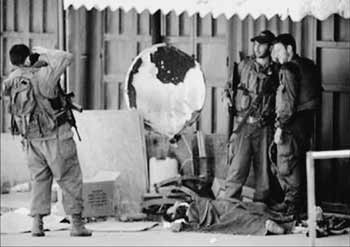

| One Israeli soldier is seen taking a photograph of two others posed standing over the dead body of a Palestinian, who it is assumed, they shot and killed. |

Fatah did not choose armed struggle from idealistic motives. Barghouti represents a stratum within the organization that has found itself, since 1994, outside the charmed circle of influence. Many of these outsiders were grassroots leaders during the first Intifada. When the PA arose, they hoped that their contributions to the cause would at last be rewarded. This did not happen. Most of the senior positions, as well as the monopolies, were taken by those who came from Tunis.

The deprived Fatah cadres bided their time. Their hour came with the onset of the new Intifada, which originally expressed the people’s hatred not only for Israel, but for the “Tunis group” too. Fatah hoped to build its own power center and thus transform the balance of forces within the PA.

The Tanzim competed with Hamas for popular support. It adopted ever more extreme methods and goals, as expressed in its new name: “the al-Aksa Martyrs’ Brigades.” Having begun with attacks on the IDF and the settlers, it switched to suicide attacks in the heart of Israel. Thus it aped the methods of the militant Islamic groups, which acted from religious inspiration, not objective analysis.

There was no long-range planning, no assessment of consequences. Not a single one of the militant groups took account of the international or regional frameworks that might be relevant to the present Palestinian situation. Had they done so, they might have refrained from total confrontation at a time when all the Arab regimes, including the PA, still adhered to the so-called “peace strategy.”

Barghouti lacked political clout, as was evident in his opportunistic attitude toward the PA. A key figure in the latter, he took part in the decision of 1993 to adopt the path of negotiations and give up armed struggle. If later he changed his mind, he should have worked to replace the PA. Instead he chose to lead the war against Israel, while relying on his immunity as a member of the Palestinian parliament. This odd policy has brought him today to an Israeli cell.

We should mention another contradiction in Barghouti’s stance. In 1993 he and the rest of the Fatah leadership adopted a “theory of defeat.” This went, in effect, as follows: “The Palestinian people has no choice but to accept the Oslo Agreement. The Arab world is against us, the Soviet Union has collapsed, and the United States is the only superpower.” Anyone who opposed this reading of the situation was accused of adventurism. In the spin given by Fatah Public Relations, the ugly duckling of defeat at Oslo became the swan of victory under the leadership of “our brother and commander Abu Omar” (Arafat).

We may ask, “What major change has taken place in the past ten years, enabling Palestinians such as Barghouti to leave their earlier defeatism and shift to a program of total war?” Just as that defeatism was wrong when the Palestinian leaders signed the Oslo Agreement, so today’s new warriors cannot square their actions with reality. They call for armed confrontation with Israel, but they lack the minimal means to carry it out or, once they start, to protect their people from the consequences.

Jenin: legend or tragedy

On the eve of Israel’s invasion of Jenin, Shirin Abu Akleh, reporting for the Arab satellite TV station Al-Jazeera, described the situation: “If the Israeli army invades the camp and carries out a massacre, this will be a defeat for it. But if it holds back from invading, that too will be a defeat. Either way, the Israeli army will wind up losing.”

This notion mirrors the distorted thinking of the Palestinian opposition groups. As the battle approaches, they admit that their armed forces have holed up in the camp alongside civilians, but they don’t describe the potential massacre as a disaster to be avoided—rather as a defeat for the enemy! It is in the nature of massacres that they expose the criminal face of the foe, but they do not necessarily bring about his defeat. (In 1948 the Israelis perpetrated several massacres, but they did not suffer defeat.) The loser is the people, abandoned to its fate with no one to defend it. Munir Shafiq, a senior pundit for the Islamic movement, calls it a travesty to equate Jenin with Sabra and Shatila. He compares the camp rather with Stalingrad. Fighters and civilians stood together, he writes. “The Jenin camp was the victor in this battle, because it rose up and killed and held out for a long time and fell as a martyr.” He proposes such martyrdom as a model for the future. (Al-Hayat, April 28.)

The two Islamic movements, Hamas and Jihad, adopted the second Intifada, but they disregarded the lessons of the first. During years of heroic popular struggle (1987-1991), Palestinian society managed to maintain its basic life-functions without bringing on itself the kind of destruction and collapse we see today. Islamic extremism views that first Intifada, nonetheless, as a chimera, because a secular leadership conducted it, and because it confined itself to the Occupied Territories, rather than striking at Israel’s heart. The new Intifada seemed a golden opportunity: Hamas would show itself as the only movement still to believe in armed struggle. It exalted individual suicide attacks to the status of a total strategic program. The Islamists consider them the ultimate weapon for defeating Israel. Khaled Mashal, a major Hamas leader recently deported by Jordan, told Al-Jazeera a few months ago: “If no one interferes, Hamas will be able to vanquish Israel within five years.”

We should bear in mind that the Palestinian problem does not constitute the central part of the Islamic program. It is one of several concerns, along with Kashmir, Afghanistan, Chechnya, the Philippines and Kosovo. The Palestinian people is largely a hostage in the fight that Hamas wages. It has no way to defend itself against reprisals. We find, with Hamas, the same disregard for the people that Osama Bin Laden had in declaring war on America, without taking account of the Afghan people—or the destruction the American response would bring.

Instead of learning a lesson from September 11 and its sequel—namely, to adjust its methods to the situation—Hamas went in the opposite direction. Its suicide attacks increased geometrically. As a result, the Palestinian people has become a target in America’s war on terrorism. The attacks enabled Washington to unleash Israel, which sallied forth.

Did anyone ask himself: “How can Hamas defeat Israel at a time when it can’t even unseat the PA?” Hamas leaps forward and the people pays the price, void of leadership and without a real program for fighting the Occupation. The Bin Laden syndrome—militant rhetoric in the absence of the power to change reality—is typical of all Islamic fundamentalist movements. In no important Arab state have they succeeded in taking power.

The need to acknowledge reality

Given the present balance of forces, Hamas with its suicide bombings cannot defeat Israel any more than the PA’s approach—through negotiation—could gain independence. Not that there is anything wrong with negotiation in itself, and not that there is anything illegitimate about armed struggle against occupation. The problem is not one of method. The decisive factor is the current balance of forces, both worldwide and regionally. This does not permit oppressed peoples today, including the Palestinians, to make significant moves toward independence.

The ability to achieve national objectives does not depend on willpower only or the readiness for personal sacrifice. It depends on objective circumstances that derive from military force, economic stability, a viable social order, and a sound political framework. None of these components may be found today among the Palestinians.

A mere eight years ago the Palestinian people was intoxicated by phony peace celebrations. It supported normalization, trusting Israeli leaders such as Shimon Peres and Ehud Barak. Today, the same thoughtlessness prevails as it squares off against its occupier, without the means to do so. Eight years of PA corruption, lies and dictatorship have not bred a single serious attempt at alternative leadership. Arafat remains the only leader in sight—without program or prospect.

Write us

socialistviewpoint@pacbell.net