![]()

Write us!

socialistviewpoint@pacbell.net

Eugene Debs on War

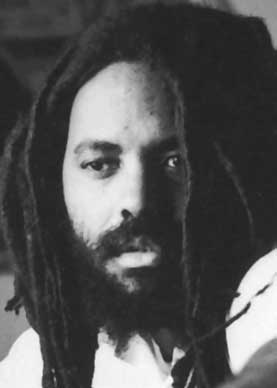

By Mumia Abu Jamal

“I have been accused of obstructing the war. I admit it. Gentlemen, I abhor war. I would oppose war if I stood alone... I have sympathy with the suffering, struggling people everywhere. It does not make any difference under which flag they were born, or where they live...”

“I have been accused of obstructing the war. I admit it. Gentlemen, I abhor war. I would oppose war if I stood alone... I have sympathy with the suffering, struggling people everywhere. It does not make any difference under which flag they were born, or where they live...”

—Eugene Victor Debs, Socialist (1918)

(To Jury at Espionage Trial)

The name Eugene Debs may not ring bells today, but in the first quarter of the 20th century, his trial rocked the nation. An ardent Socialist, Debs made plain his opposition to the War, and more importantly, his opposition to the class character of the war; that it was a war waged by working people for the wealthy. A powerful, and stirring orator, Debs drew waves of applause from those who came to hear him. He also spoke plainly about war and the wages of war:

“They tell us that we live in a great free republic; that our institutions are democratic; that we are a free and self-governing people. That is too much, even for a joke... Wars throughout history have been waged for conquest and plunder... And that is war in a nutshell. The master class has always declared the wars; the subject class has always fought the battles.....”

[fr. Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States (1995), p. 358]

Debs, charged with violating the Espionage Act, was convicted of obstructing the draft for giving this speech, and a unanimous U.S. Supreme Court would affirm his conviction a year later. The imprisoned labor leader, convicted of exercising his alleged first amendment rights of speaking out against an unpopular war, would write his stirring, Walls and Bars: Prisons and Prison.

Life in the “Land of the Free” (1927). Nominated by the Socialist Party to run for President in 1920, Debs received nearly 1 million votes—while behind bars!

Nor was Debs alone in his opposition to the war, as papers of the time attest. The Minneapolis Journal would blare “Draft Opposition Fast Spreading in State”. Over 300,000 men evaded the draft for the “War to End All Wars” (as it was called). Working people demonstrated against the war all across the nation, and were attacked by cops and soldiers, under orders of the brass. Tens of thousands of men claimed conscientious objector status. What is clear is that antiwar sentiment didn’t just sprout up during the unpopular Vietnam War in the 1960’s and 70’s.

Being antiwar is part of the historical fabric of America.

Although it may surprise us in this age to speak of him thus, Abraham Lincoln was famous before his presidency, for his outspoken opposition to the Mexican-American War (1846-48) when, as a member of Congress, the Illinois delegate challenged President James Polk to specify exactly where American blood was shed “on the American soil.” (The pretext for the Mexican War). As a Whig, Lincoln was outspoken on his Party’s position:

“The declaration that we have always opposed the war is true or false, according as one may understand the term ‘oppose the war.’ If to say ‘the war was unnecessarily and unconstitutionally commenced by the President’ be opposing the war, then the Whigs have very generally opposed it.” [Zinn, 151.]

Historians who now review the basis for the Mexican-American War generally agree that the White House used a lie to justify it.

We have mentioned the Vietnam War. Who can question the outspoken contributions that the heavyweight boxing Champ, Muhammad Ali, or Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. made to challenging and ending that fevered carnage in the Far East? Ali’s famous phrase, “No Vietnamese ever called me ‘nigger,’” shone a garish light on the plight of Blacks in the country, who were asked to defend a “democracy” abroad that was sorely lacking at home. Dr. King’s speeches against the War earned him the enmity of his liberal fair-weather “friends,” and caused the corporate press to attack him relentlessly for treason, yet who, some 30 years later, can remember the catcalls of his critics, when compared to the excellence and ethics of his dissent against the rampant militarism of the War. Dr. King’s proclamation that America was the “greatest purveyor of violence in the world today” is found in the mouths of tens of thousands of antiwar protesters in America who weren’t alive when he said it, and is repeated in a hundred different languages around the world to legitimize a global antiwar movement of millions who oppose the American way of War.

To paraphrase the former Rap Brown (now Imam Jamil Al-Amin), “Dissent is as American as cherry pie.”

—Copyright 2003, Mumia Abu-Jamal

Write us

socialistviewpoint@pacbell.net