![]()

Write us!

socialistviewpoint@pacbell.net

by Walter Lippmann

There are many ways Habaneros get around their sprawling city. The largest and most inexpensive of these are monster buses assembled in Cuba and nicknamed “camello” (the camel) because of their distinctive shape. The fare is extremely cheap, 20 Cuban centavos (remember: that equals one US penny!) and they’re often very crowded. Pickpockets are also known to “work” them, so I was told to put my wallet in my front pocket or in a briefcase for security. I was also continually amazed to see military officers taking their places in line for the bus, just like everyone else. They don’t have special privileges because they’re in uniform.

Electricity: During the worst of the “special period” in the 1990s, extensive, planned electricity blackouts occurred regularly for energy conservation. In late 2000 it was announced that these would end. However, during my two-month stay, there were four blackouts. Each was only few hours long. They were localized (just within our immediate area) and apparently due to structural weaknesses in the system. They were often connected with rainfall, not planned as energy saving measures. Perhaps the main thing they did was remind people to carry a flashlight, which many did not have. Wor kers from the electric company are very popular and, from what I’m told, very well paid. They get lots of overtime!

Pocket flashlights and batteries are a nice gift for visitors to bring. Having your own flashlight marks you as a knowledgeable visitor and not a newbie. Once I was back in the US, California began to have major power outages as private electricity companies forced prices through the roof.

Taxis fill in where buses can’t. Metered taxis with fares in dollars are the most expensive, but many are air conditioned and extremely comfortable. There are companies which respond to phone calls. The best known is PanaTaxi, which you reach by calling 55555. They were not always reliable, a big change from the previous year when I recall such cabs responding quickly.

Cabs can also be found by standing at the curb and hailing one or just looking as if you need a ride until one of them stops and the driver asks where you’re headed. A third cab system has been created, the “coco cabs.” These are small, round open-air vehicles, seating two or at most three behind the driver. You don’t want to use one of these on a cold (by Cuban standards!) day. Fares are negotiable, in dollars, before departing. More women serve as drivers of these than of traditional taxis.

The “ten-peso cab” system also works quite well, especially if you’re Spanish-speaking. These cabs are ancient but fully serviceable cars; they go extremely long distances, but only in one direction. The driver will pick up as many passengers as possible, so you can find yourself riding with five or even six other people. Friends told me not to speak as the drivers could get in trouble for transporting a foreigner, for which they were not licensed. I never had problems getting rides.

Some Cubans are licensed to transport people in the old luxurious classic cars for which Cuba is so famous. I heard that the licenses are expensive, and that the government stopped issuing them some time ago, despite a demand for the services.

One day while seeking a taxi, I was approached by what was to be the most comfortable ride I had in Cuba: a late-model Mercedes-Benz. The driver (who already had another passenger) said his regular job was as chauffeur for a high government official. He had the day off, and used his boss’s car to pick up some dollars moonlighting as a jitney.

Also there are the “bicitaxis.” These are powered by one person in front, on a bicycle frame, with two elevated seats and a sunshade in the rear. They’re slow and not easy on the body due to the deferred maintenance on many streets.

Parenthetically, the Cuban military is required by regulation to give people rides if their vehicles have room, and they actually do this. And there are also people who drive others around for money but who aren’t licensed for this. I used all these modes of getting around, except for military vehicles, which I almost never saw.

Cuban streets are rarely crowded and I never saw what I would call a genuine traffic jam as in Los Angeles. Perhaps a better comparison with Cuba would be Mexico City. There, the streets are strangling with cars (and their attendant pollution), including an inordinate number of Volkswagen beetles. These aren’t the new kind we’ve seen in the US in recent years, but the traditional beetle, painted green and white. In Mexico, where the VW is still built, it’s the most widely used vehicle for taxis. The front passenger seat is removed so there’s only room for two riders in the rear.

Women of all ages hitchhike in Cuba with no fear for their safety! Cuba is absolutely different from the United States, Mexico or many other countries in this. I know a journalist at Radio Havana Cuba who lives thirty miles the city and has no car. She hitches to work and has no worries about her safety. This would be INCONCEIVABLE in any US city.

You can walk around the city without fear. Havana is rather dark at night because there aren’t enough street lights. The biggest safety problem I saw was how much the sidewalks need repair. As one who loves to take long early morning walks in Los Angeles, losing myself in thought, I learned quickly in Cuba to literally watch my step! In general, it was the SAFENESS of Cuba which for me was most palpable. I felt far safer there than in Los Angeles.

John Lennon in Havana

Popular music from the US is big on Cuban radio and there is also a thriving informal market for bootleg US music on tape and CD. On December 8, 2000 Cuba unveiled a statue to John Lennon as part of the observance for the 20th anniversary of Lennon’s death. Leading members of the government, including Fidel, attended the event. National Assembly President Ricardo Alarcon gave an eloquent address placing Lennon’s life and music in historical and political perspective. Alarcon’s remarks and my photo of the statue can be found here at NY Transfer’s website: http//www.blythe.org/.

The US media has been working overtime for 3 decades to counteract the political radicalism of the Sixties. It’s all the more significant that Cuba does what it can to keep the values of that period alive in the minds its people. (Ironically, during the Sixties Cuba was not so enthusiastic about such cultural forms of protest.)

[John Lennon Concert, Havana] Imagine... John Lennon Concert in Havana, December 8, 2000

The evening of the statue’s unveiling, a large outdoor concert of Lennon’s music attracted thousands of young Cubans who often sang along with the songs, in English. A pair of on-stage disc jockeys announced the various groups and songs. A massive video projection system with 16 screens displayed images of Lennon performing on film while the Cuban singers and musicians played. Security was present, but it wasn’t heavy-handed. Mainly it directed audience members to where they should sit or stand. None wore uniforms or guns. Taking pictures I walked up within fifteen feet of the performers on stage and no effort was made to stop me.

At a similar event in the United States, you’d find the sweet smell of marijuana, but not in Cuba, and almost no one was drinking alcohol. Everyone was having a good time and no one was drunk, loaded or otherwise out of control.

Word had apparently gone out that people in the audience shouldn’t smoke or drink. It seemed significant that this should even be mentioned since Cuba’s so firmly anti-drug. This must be what a Christian rock concert feels like. Lennon’s music represented a cultural-political protest against injustice in US society in its time, but it could hardly have that significance in a place like Cuba where a revolutionary government is in power. Yet Lennon’s music clearly resonated deeply for this audience.

Advertising

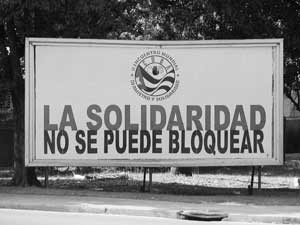

The lack of billboards in Cuba is striking. There are some political signs, though not many. One, announcing the November, 2000 International Solidarity gathering, simply said “Solidarity Can Never Be Blockaded.” And there are virtually no commercial signs of any kind. Businesses have signs on their buildings, but overall the lack of advertising, which shrieks at you in the US and Mexico, was amazing and pleasing.

Brand name products are more popular than generics, even though generics can be much cheaper. I thought I’d kid my Cuban friends about how they had swallowed capitalist advertising when I discovered they preferred Close-Up (“the sex-appeal toothpaste”) to the generic, which comes in an unmarked tube. The generic costs literally pennies on the Cuban ration book (the libreta). The Cubans, however, handed me the Close-Up tube with these words at the bottom: “Hecho en Cuba por Suchel Levar, Havana, Cuba por acuerdo con los propietarios de la marca.” (“Made in Cuba by Suchel Levar [a Cuban state enterprise] by agreement with the owners of the trademark.”)

Cuban television

As in the US, Cubans often turn on their TV sets and walk away, leaving the sound on as a kind of background noise in their lives. TV seems the main place where people get news and entertainment. As one who rarely watches at home, I found Cuban TV fascinating. I watched also to help learn Spanish.

Cuba only has two television channels, Cubavision and Tele-Rebelde. It’s not on 24 hours a day. The formats are similar to what we might see in the US, but there are striking differences. Imagine television without any commercials at all!?!? There are NO commercials of any kind. They had a few public service announcements (don’t waste water, conserve electricity, smoking is bad for your health, don’t abuse alcohol, and so on). These were short, under a minute each, and not heavy-handed.

Movies from all over the world are broadcast, some in their native languages with subtitles, some dubbed. “Murder, She Wrote” (dubbed) is very popular. I enjoyed the sweet and sentimental “Stuart Little” (dubbed) followed by a documentary on the making of the movie “Honey, I Shrunk the Kids,” (subtitled). A German mystery series called “Decker” is also popular.

One evening in a beautiful, completely refurbished old hotel in Central Havana they were watching (I kid you not!!) “The Brady Bunch” (dubbed in Spanish). Telenovelas are big, including one taking place in Cuba during slavery. Others from Brazil, Argentina and other Latin American countries are popular. Cuban music of all styles, from son to salsa to bolero and hip-hop, is also broadcast.

News programs cover basic topics: Cuban diplomatic activity, international meetings, and so on. We would recognize familiar formats. The content however, is quite different. The evening newscast begins with references to that day in history, from the 19th century to the present. Every day some historical or political event was being marked, either on TV or in public gatherings. I also saw an extended PBS documentary about the mistreatment of immigrants by the INS on Cuban TV.

During the struggle to recover Elian Gonzalez from the US, a nightly feature was the “roundtable,” a program of news analysis by Cuban journalists and academics taking up current events. Activists and scholars from outside Cuba are called for their opinions. Since Elian’s return, the roundtable has become a staple. It has an in-studio audience, but they are observers, not participants in discussions. Once in a while Fidel appears on the show, but not while I was in Cuba.

Cuba promised that once Elian was repatriated, the voyeuristic US television coverage would be ended. This pledge has been kept. The child and his family are rarely seen on TV, except for the birthday party at his school on December 6th. Fidel spoke briefly, as did Juan Miguel. Otherwise, the entertainment was children singing, clowns performing and a monster birthday cake.

Interviews with Cuban-Americans such as Francisco Aruca, a Miami businessman and radio personality who favors normalization of relations, are regularly featured in the Cuban media. Aruca, who had opposed the revolution years ago, now runs a travel agency that brings Cuban-Americans to the island for family visits. During Fidel’s trip to Mexico, the roundtable featured an interview with Peter Gellert, a key organizer of Cuba solidarity activity in Mexico. Gellert, an old friend, was born in the US and was an activist in the 1960s. We met as members of the US Socialist Workers Party then.

Political participation

Public participation in political life takes several forms. I observed and participated in several. Most familiar to foreigners are the political rallies and marches. These are frequently used by the US media to depict Cuban life. They became a staple during the Elian struggle and they continue. Elian was the best-known of the hundreds of thousands of illegal Cuban emigrants whose nearly lethal trip to the US was encouraged by the Cuban Adjustment Act.

To educate the public about the dangers of illegal departures, Cubans have continued to mobilize. Rallies and marches occur weekly throughout the country. Sometimes Fidel Castro speaks and sometimes he doesn’t. Sometimes he speaks at length, sometimes not. He’s in many ways a larger-than-life figure. People wonder both how and why Fidel speaks so often and at such length. Much of what he says in these speeches (and I’ve both listened to and read quite a few) are familiar. At times they seem repetitive. I don’t have the patience to listen for hours at a time.

But of course, Fidel isn’t speaking to people like me. He’s explaining the political realities to young Cubans who may not grasp what’s happening, and to older ones who may have forgotten, or who may have never understood. Some Cubans find his speeches boring; many don’t listen to them all the way through, but I was amazed at how many did listen all the way through, and no one was obliged to. You can switch to another station or just turn it off.

A danger seems to be the generation gap. The Cuban government knows that problems can come from a generation that has access to more, and knows more about the things they cannot have, than earlier generations. Younger Cubans at the same time do not know first-hand of the suffering, poverty, malnutrition, and exploitation that existed before the revolution. Hence Fidel’s heavy attention to the youth. Hence the appointment of Felipe Perez Roque as foreign minister. At 34, Roque is probably the youngest foreign minister in the world. Hence their big emphasis on sports, diplomas and other forms of public recognition.

Cuba has a one-party political system. This means that the big political decisions are centralized in the hands of the party, and, within that, by its leadership, headed by Fidel. The other parties which existed prior to the triumph in 1959, and which remained afterwards, refused to accept fundamental change when it occurred. They went over to support the illegal and armed opposition. The Cuban Communist Party itself was a fusion of three predecessor organizations, and has not had a split since its founding in 1965.

In an ideal world (we don’t live in one), it is healthy for society if a range of views and policy alternatives can be publicly discussed and debated. So long as the United States has the overthrow of the Cuban Revolution as its policy #1, Cuba cannot have a multi-party system. There are consequences flowing from this (good and bad), but Cuba has little choice but to organize itself as it has, in my view. I don’t make a virtue of this necessity. It’s just what Cuba needs now.

An authoritative explanation of the Cuban approach can be found in the book Heirs to History, which lays out Cuba’s policy of uniting all who support the revolution into a single political party. It begins with an essay by Jose Marti, and includes explanations of the concept in depth by Fidel Castro and leaders of the old Popular Socialist Party, Fabio Grobart and Juan Marinello.

Troublemakers caught

Days after I left, two Czech citizens were detained by Cuban authorities after meeting with opponents of the government. They had come after visiting a New York-based organization called Freedom House, an acknowledged conduit for CIA funding of right-wing groups. Although they had received Cuban tourist visas, they were not vacationing sightseers. They brought money, tickets and a computer to pass on to their Cuban contacts. This caused a media flap for a few weeks.

The Czechs were released, as Cuba said they would be, after publicly admitting what they had done and offering an apology. Cuba keeps close tabs on such visitors because it is the official policy of the US, under Helms- Burton, to use proxies such as these to foment trouble and subsidize counterrevolutionary activities. Not long after this we saw the US spy plane which crashed on Chinese soil. The lengths to which the US went to avoid apologizing to China for this incursion into its airspace gives a sense of how politically significant such apologies actually are. When we read about the limits Cuba is said to place on the internet, situations like these show Cuba has reasons for its concerns.

Burton, to use proxies such as these to foment trouble and subsidize counterrevolutionary activities. Not long after this we saw the US spy plane which crashed on Chinese soil. The lengths to which the US went to avoid apologizing to China for this incursion into its airspace gives a sense of how politically significant such apologies actually are. When we read about the limits Cuba is said to place on the internet, situations like these show Cuba has reasons for its concerns.

The Czech story got lots of coverage, but it was hardly the only example of such efforts. The very day before I left, Spanish officials had organized a provocation. Using the Spanish Cultural Center, a celebration of the Roman Catholic “Three Kings” festival was organized. Actors portraying the religious figures paraded through Central Havana, inviting children to their building, and tossing out candy and toys. Once the children got to the center, they were chased away.

This created a semi-riotous situation, and Cuban camera crews were present to document it. The events were broadcast on TV that evening, with minimal commentary. Viewers saw for themselves Spanish actors trying to create some kind of public disturbance. The Cuban media then broadcast tape of other festivities involving children which all went off peacefully at the same time...

Public participation for social needs

Periodically Cubans are asked to do voluntary work. It’s unpaid and typically occurs on Saturdays. Some workers go to their offices and do maintenance work. Some go to the countryside for serious physical labor. This was a practice initiated by Che Guevara, who originally said it should be every weekend or every other weekend. I was invited by Mike Fuller, a US citizen working at the Prensa Latina news agency, to join him and his workmates. About 125-150 showed up. We went by bus to a farm in the Guanabacoa suburb of Havana. Our choices were to cut sugar cane, to cut weeds with machetes, or to haul large construction blocks by hand. We ranged from young adults to people in their fifties and sixties.

Hauling large cinder construction blocks seemed the simplest task, so I chose that. I balanced the blocks on my head. Soon there was a long line hauling the blocks all the way from where they’d been unloaded by the delivery truck to where a building would be put up. After a time, the group spontaneously changed its method and we all began either passing or tossing our blocks from one person to the next. The work proceeded much faster that way, and we each had many micro breaks working as a team instead of as individuals. It was a long, hard task! I worried I might not be able to move the next day. (I had no problems the next day, which I attribute to my vigorous yoga practice.)

One participant (using a cane and working with a machete clearing underbrush) was the 66-year-old supervisor of the translation department at PL. His staff of Cubans and foreigners translates Spanish into other languages for distribution around the world. No one made him or anyone else to come out. He simply responded out of a sense of civic responsibility. It’s how work gets done for which wages and workers are unavailable. At times we took breaks and shared some rum (which we’d chipped in to buy), but I can assure you we worked very, very hard.

We had a delicious hot soup and ice water for lunch. On the way back to town there was lots of group singing. It reminded me of summer camp. And, no, the songs weren’t political, just folks who’ve been having fun, and participating in their community.

Racism

Relations between black and white Cubans struck me as very different from the situation in the US. Cuba’s population has a far higher proportion of black and mulatto people than the US. Wherever I went, I saw Cubans of all colors in relaxed and friendly contact, including couples. This is much more rare in the US. My sense, from talking with black and white Cubans, is that Cuban racism is a cultural legacy from the past which hasn’t been overcome, even after 40 years of revolution.

In Cuban society, difficult issues are addressed in many ways, including in TV dramas. I saw one TV program that focused on racism. It portrayed conflicting reactions within a blended family in which the college-age daughter (white) falls in love with a black schoolmate. As the program begins, the girl’s mother is delighted with her daughter’s previous (white) boyfriend. When she breaks up with the white boy and starts seeing a black one, her mother freaks out. The young couple are shown making love (in very tasteful silhouettes) and when her mother discovers them, she goes ballistic.

The mother, we learn, is married to a mulatto (not the girl’s father), and he protests his wife’s prejudiced attitudes. The husband eventually leaves her after she admits the real reason she’s never had children with him was his race. The young woman also eventually leaves home, after much soul-searching, to be with the man she loves. As the closing credits scroll, we see a baby carriage. The camera pans up to show the girl’s mother, happily pushing the carriage. Finally we see the happy young couple, black and white, as the program ends. The arrival of the grandchild ultimately reconciles mother to daughter.

Focusing on this issue in a direct but not heavy-handed way tells me Cuban TV programmers are trying to address such expressions of racism. I also observed such racist attitudes among people who otherwise support the revolution.

Looking around in tourist hotels, dollar malls and restaurants, I noticed considerably fewer black faces than I did in Cuba generally. Some black Cubans commented on this when I asked about it. These same black Cubans also said that Cuban racism, with which they themselves were quite familiar, is neither institutionalized nor backed by the violence and bigoted justifications used in the US. In Cuba today, it would be impossible to publish the kind of books or articles that have been issued recently in the US, arguing black inferiority. Cuba’s political culture simply wouldn’t permit it.

Gender politics in Cuba

The top leadership of the Cuban government and the Communist Party are mostly men, but the majority of professionals and technical staff today are women. Women’s increasing role in the workplace and outside the home is affecting relationships, though Cuban culture remains male-dominated. These demographic shifts are reflected in the media. Cubans I met had a more relaxed, more natural (and healthy) attitude toward sexual matters in general than prevails in the US.

Abortion is legal and completely free, as are all medical services. There is genuine concern about the over-use of abortion as a form of birth control, but absolutely no consideration of outlawing the procedure. Too many abortions can lead to scarring, infections, Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) and infertility. It is also much more expensive for the public health system to provide abortions instead of contraceptive services. So Cuban authorities don’t want to see everyone running in for abortions every time they have sex. Over-use of abortion became a significant health problem in Eastern Europe. (Now that the capitalists are back in in charge, they have gone back to the dark ages where women’s reproductive freedom is concerned. Cuba doesn’t want to repeat that pattern.)

At the same time, there’s also concern about Cuba’s low birthrate, since this demographic shift can have destructive social and political consequences. It will make it harder to support an aging population, and to keep agriculture going, since rural young people are increasingly reluctant to stay on the farm.

Strong emphasis is put on the use of condoms and other safer sex methods. People griped about the poor quality of Chinese condoms, which break easily, so Cuba may soon manufacture its own. Cubans call them “preservativos,” not “condones.” Public service spots on Cuban television invariably depict heterosexual couples.

Gay rights in Cuba

Gay rights in Cuba

The mid 1960s through early 1970s were a time when gay men experienced harsh repression by the Cuban government. Gays were forbidden to enter some professions, like teaching. Some were rounded up and placed in camps euphemistically called Military Units to Aid Production (UMAP). It was a shameful period. It lasted several years. But it ended. Homophobia still exists, but it’s not institutionalized, and it’s not considered acceptable in polite conversation.

Thinking about that period, it’s useful to recall that it occurred prior to the Stonewall rebellion (1969) and the rise of the modern gay liberation movement. Homosexuality was still viewed as a psychiatric disorder. The political left, probably reflecting social prejudice, was indifferent, if not hostile, to gay rights.

The practices of the past in Cuba were rooted in the traditional homophobia of its culture, from what I could tell. The Roman Catholic Church and its Spanish priesthood were key to this. Cuba’s ties to the Soviet Union, whose governing ideology included the stupid and reactionary concept that homosexuality is a product of “capitalist degeneration,” exacerbated this problem.

The movie “Strawberry and Chocolate” (“Fresa y Chocolate”) is widely seen in Cuba as an implicit apology for the repression of that period. The movie is widely available for sale in Cuba. One of its stars is Jorge Perrugoria, a prominent Cuban actor who happens to be heterosexual. No one commented that it might hurt his career to play a gay role.

Decades later, Cuba’s period of repression continues to be used by opponents to portray the country as a terrible place for everyone, especially for gay men. The movie “Before Night Falls,” based on a wildly imaginative memoir by Reinaldo Arenas, shows why the status of Cuban gays is still an issue Cuba solidarity activists need to be attentive to. The movie is worth an entire essay. Fortunately, that essay has already been written by Los Angeles activist Jon Hillson, and you can read it on the web at NY Transfer, in English and Spanish.

Today, the problems facing lesbian and gay Cubans are largely cultural, not institutional. Gay Cubans aren’t beaten and killed as in the US. In his 1996 book Machos, Maricones and Gays: Cuba and Homosexuality, Canadian scholar Ian Lumsden, while very critical of modern Cuban life, documents the ending of institutionalized discrimination against Cuban gays.

In 1999, the Cuban publishing house Editorial Ciencias Sociales released Homosexuality, Homosexualism and Human Ethics (ISBN: 9590603920), by Pedro de la J. Cruz, a professor and researcher at the Cuban Academy of Sciences. The author teaches at the Nico Lopez Advanced School of the Communist Party as well as at a university. His book places gay rights in an international historical and cultural framework and its tone is very sympathetic. A translation for an English-speaking readership would be extremely helpful. Evidence of homophobia arises now and then. Early this year a homophobic article was published by La Tribuna, a Havana newspaper. There seems to be no organized way within which lesbian, gays and their friends in Cuba can take these up. Cuba’s opponents, who don’t support gay rights, hypocritically try to use such things to turn people against Cuba. There are no explicitly gay or lesbian organizations, but there are informal meeting places, like Coppelia and the Yara theater. I saw men in drag not experiencing police harassment. And there are informal networks through which people socialize and keep in touch. I had no trouble finding folks.

Few legal lobbying organizations exist in Cuba. Gay groups were organized in the early 1990s, but they were asked to dissolve when provisions of the Helms-Burton law made Cuban authorities worry that the groups could be targeted for infiltration and disruption. But perhaps if Cuba had a group like PFLAG (Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays), such issues could be addressed better. In the US, PFLAG works ceaselessly to support the rights of lesbians, gays, bisexuals and the transgendered, confronting ignorance and prejudice in society. Though I met many gay men who were open and out of the closet, I met very few out lesbians. There must be a lesbian world in Cuba, but it’s apparently closeted. So while I wouldn’t describe Cuba as a “gay-friendly” place, it’s certainly not “gay hostile.”

Alcoholism

Alcoholism is a problem in Cuba, just as it is everywhere else. A growing Alcoholics Anonymous movement reflects this. It’s not officially recognized, and most meetings are held in churches, but it’s the same AA as in the US, where most meetings are also held in churches. It began within the past ten years, initially by people from the US. Cuba’s suspicion of US groups led the Cuban branch to obtain support from the Mexican AA.

In Vedado I attended an AA meeting, held in a secular setting, at the Jose Marti School of Journalism. About twenty people came and I was told it’s one of a hundred or so such groups in Cuba, of similar size. Literature was available about a national AA gathering later in the year. I saw a public service announcement on TV discouraging alcohol abuse. Oh, yes, they smoke cigarettes at AA meetings.

Lots of alcohol is drunk in Cuba, at all hours of the day and night. It’s a big part of the culture. People in offices will pull out a bottle of rum from their desks and offer you a drink. Yet I never saw anyone drunk, or even tipsy, in a work setting. In fact, I never saw anyone drunk in any setting. Since liquor is a important foreign exchange source, it’s a good sign that its abuse is acknowledged.

Crime and safety

Cuba is an extremely safe place compared with the US, where interpersonal violence and murder are widespread. Killings and other violent crimes are rare in Cuba. One day I noticed three heavily armed guards (with machine guns and wearing bullet-proof vests) picking up cash at a popular bakery in Central Havana. An armed robbery had taken place some months before and a security guard was killed. It caused such a sensation that armed guards now pick up the cash at places such as this. (Business is extremely good at the bakery, which takes dollars only, and there is an endless stream of customers all day long.)

The story of the robbery was told to me with utter incredulity because it’s so unusual in Cuba. While I saw security guards and police officers in places like banks and hotels, I only saw two such armed squads during two months in Cuba. By contrast, in Mexico City I saw armed guards, identically decked-out, at literally every large office building. People take very serious precautions to protect their homes and property. Iron bars on windows are ubiquitous. The friends I stayed with reminded me firmly and often to close and lock all windows and doors whenever I went out of their second-floor apartment. This included doors and windows behind the chain-link fence which completely encloses their porch. This fencing was installed since my visit the previous year.

A light bulb went out in the external hallway where I stayed. I needed a ladder and had remove a secure housing with eight individual screws to access the old bulb and replace it. From what I could hear and see, least in Havana, there is a heightened sense of the danger of crime. US visitors find this amusing, since there is so little actual crime. But the fact of a few robberies, one or two muggings, and a random killing is enough to make everyone in the capital nervous about their property. That says a whole lot about how safe Cuba actually is. This is in the major cities only, where they have experienced the influx of tourism, friends explained.

Business matters

I was surprised to find that there’s even a Cuban Chamber of Commerce. It meets regularly with foreign counterparts to learn about improving business efficiency. The Chamber has an attractive slick bi-monthly journal. Each issue is fully bilingual, in both English and Spanish. There’s also a weekly newspaper, Negocios en Cuba (Business in Cuba) covering economic and trade developments.

For Cuba to compete effectively for tourist business, it needs to learn about and from its competitors. This seems to be happening. I was very impressed by the beautiful modern hotels and institutions. These are fully modern institutions, up to the highest international standards. One evening I attended a fashion show, with male and female models in Cuban-designed and made outfits. The editor of Negocios en Cuba proudly told me that young Cuban women had won two beauty contests in recent years.

Some businesses which mainly serve Cubans would drive one used to US department stores or Home Depot crazy. It was impossible to find a simple medicine cabinet to replace a broken one in my hosts’ home. And it was nearly impossible to find a flashlight, which is needed for the occasional power outages. Being required to check one’s briefcase or bag to enter a store is annoying though Cubans are, as I said before, “acostumbrado.”

And especially in some of the smaller businesses, proprietors sometimes display a gruff hostility toward the public. I rarely heard the words “Please” and “Thank you.”

Overall thoughts

Cuba is a society that works. It has all sorts of problems, but it works! Unlike any other on the planet, medical care and education remain fully free today. The loss of the Soviet bloc knocked out its economic stability and threw it into a tizzy. Cuba’s foreign and economic goals are to retain the past gains of the revolution. In a word, survival is its first priority. Cuba now strives to retain as much of its economic and political independence as it can.

The revolution would probably not have survived had Cuba not allied itself with the USSR. Cuba received big benefits but paid a high price. Revolutionary struggles such as were occurring in the 1960s and 1970s are not occurring today. Virtually the whole world has remained capitalist or turned toward capitalism.

This is why every act of solidarity is vitally important. Possibilities are endless: speaking to a single person, writing an article or a letter to the editor, sharing information over the internet, encouraging people to support Cuba in a practical way by going there, and acting to change the policies of the US toward Cuba are all vital. None should be counter posed to one another. Cuba needs all the help it can get to defend its sovereignty and its revolution.

Cuba’s biggest problem comes from Washington. US efforts to overthrow the revolution and return Cuba to dependent subservience are Cuba’s biggest problem. The Cubans have made some big mistakes of their own. If Cuba didn’t have to spend so much time and effort defending itself against the US, I believe it could have avoided or corrected many of these earlier and more easily. Though it’s great to go there, it’s probably more important in the long run to concentrate on solving Cuba’s biggest problem up here.

Write us! socialistviewpoint@pacbell.net