![]()

Write us!

socialistviewpoint@pacbell.net

November 2003 • Vol 3, No. 10 •

African Holocausts

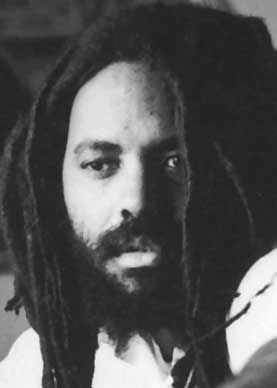

By Mumia Abu-Jamal

“Hiti ndiheagwo kiri”—(One does not give a person to a hyena twice)

“Hiti ndiheagwo kiri”—(One does not give a person to a hyena twice)

—African proverb (Gikuyu)

It is virtually impossible to view reports of the carnage ravaging Africa without wondering; Why? How? Can it ever get better?

The newly liberated Africa of the 1960s was a beacon of hope, promising a bright tomorrow for a continent bled for centuries under European colonialism. That promise has not come true for hundreds of millions of African people. Indeed, the last half of the 20th Century may be termed a nightmare of violence, war, loss and death.

The nightmare goes on, into the dawning years of the 21st Century, As certainly as it did the 20th. Is there any hope?

Those who have read these columns for some time will recall references to the Kenyan human rights activist, and former political prisoner, Koigi wa Wamwere, who wrote a remarkable book about Kenya’s years of Western-supported dictatorship under both the Kenyatta and the Moi regimes. Wamwere told a harrowing tale of political repression and brutality under both governments in his I Refuse to Die: My Journey for Freedom (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2002).

Wamwere’s latest work, while centered in his Kenyan experience, delves into the itchy problem of intra-tribal violence in African life, and in a brief 208 pages, examines what he calls “negative ethnicity.” Wamwere argues that ethnicity, standing alone, isn’t the problem; yet the political and economic elites in various countries utilize this “negative ethnicity” to divide the people, and protect their upper class privileges, by appealing to the lowest common denominator: tribe against tribe.

The result? What begins as personal and communal biases explodes into inter-communal, often bi-national violence, that splits communities and nations asunder.

In his latest book, titled Negative Ethnicity: From Bias to Genocide (New York: Seven Stories, 2003), Wamwere explains recent outbreaks in Kenya, Nigeria, Sudan, Rwanda, Uganda, Burundi, and other African hotspots. Wamwere explains that national elites use the social distinction of ethnicity to keep people concentrated on their neighbors, rather than their leaders. Thus, the “enemy” is the nearest tribe, never the state; and never the exploiting class which appropriates the powers and privileges of government. Wamwere cites one example:

Martin Shikuku, a former member of the Kenyan Parlliament and government minister, used to say that Africans are cursed. This is why we have suffered so much, why we hate and fight each other. Yet all people are born with a capacity for both good and evil, and all people have the impulse to fight. The only curse Africans suffer is the greed of our elites, who for their own gain promote hatred and wars. I asked many Africans why we hate and fight among ourselves, and several explanations emerged: personal gain, political gain, jobs, business, land. A Nigerian friend, the late Chief Victor Nwankwo, who was assassinated on August 29, 2002—God rest his soul in peace—put it well: “(Negative) ethnicity is a personal quest for resources in a tribal toga.” (Negative Ethnicity, Wamwere, p. 68-69)

At first glance, the prospect of ethnic rivalry in Africa seems perplexing to African-Americans, who cannot fathom how such bitter and violent conflicts develop among all Black peoples in African countries. What is lost on African-Americans is the meaning of tribe: the very foundation of one’s identity.

And yet, Black Americans who may look down their noses at African tribal wars often live in urban centers where equally mindless gang warfare has made life all but unlivable.

The solution? Wamwere believes that the first step is to honestly acknowledge the problem, and then to confront it with ideas. He advocates the emergence of multi-ethnic political parties and socially progressive groups. He advocates socialist humanism, which accords to each person the respect of the other. He advocates the establishment of Nkrumah’s dream of a United States of Africa, where the calls of clan, tribe and ethnicity can be lessened by a greater sense of the whole. He advocates no less than a rebirth of the ancient ancestral homeland of humanity—Africa, which is necessary for its very survival.

He advocates life.

—Copyright 2003, Mumia Abu-Jamal

Write us

socialistviewpoint@pacbell.net