![]()

Write us!

socialistviewpoint@pacbell.net

Two Months in Cuba:

Notes of a visiting Cuba solidarity activist

By Walter Lippmann

Part 2

The following are excerpts from a longer essay, TWO MONTHS IN CUBA by Walter Lippmann.The complete text of it is posted to the NY TRANSFER NEWS COLLECTIVE website: www.blythe.org

The photographs are by Walter Lippmann unless otherwise noted and more will be found on that web site. He is a solidarity activist in the Los Angeles area and has supported the Cuban revolution for more than forty years.

E-mail to the author is sent to walterlx@earthlink.net

Waiting in Line

Lines at the market, at the movies, at the bank and waiting for the bus. Lines are a constant feature of Cuban life. The Spanish word for “line” is “la cola” and the word for “last” is “la ultima,” as in “Who’s last in line?” There was one truly striking thing I experienced several times. Suppose people were lined up, waiting for a bus. It came and filled up. But some couldn’t get on and they had to wait for the next bus. The line would break up and people would stand or sit wherever. When the next bus came along a bit later, people quietly resumed their previous place in line.

People would come up to me and ask, “la ultima?” (“Are you the last?”) and then get in line behind me. I was amazed by this self-organized responsibility, coming from the US where everyone tries to be (has to be?) first in line, or to drive the fastest, or whatever. When I asked how they cope with the lines, the poor phone service and so on, I most often heard the word “acostumbrado” (“I’m used to it.”) It’s so commonplace most people don’t even think about it.

At times I felt that workers who deal with the public should have to watch the movie “Muerto de un Burocrata” (“Death of a Bureaucrat”) at least once a year. This famous Cuban comedy shows how crazy things can get when rules are inflexibly enforced. Such experiences could be extremely frustrating. Yet on many other occasions people went out of their way to be helpful and to explain how to get around such bureaucratic hassles.

Supplementing incomes individually

Last year I saw a few people begging. I was told these people were mentally ill. This year there seemed a few more. It was still a handful, far less than in the US, but those I saw were men missing one or both legs. They sat on the ground or stood on crutches, with a forlorn expression, holding a cardboard box in which passersby were meant to throw coins. They also were clutching small hand-made figurines of men with missing limbs holding crucifixes. This seemed very strange, because Cuba makes its own prostheses and trains people in their use, and there are organizations that work on the rights of the disabled, the blind, the deaf and so on.

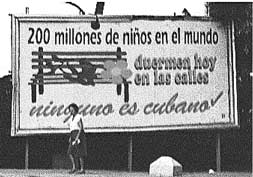

Cuban Vice-President Carlos Lage told a 1997 UN conference, “Two hundred million children sleep in the streets in the world today. None of them is Cuban.” Lage’s comment was posted on Cuban billboards. This was the Cuban reality that I saw. Yet, there are some adults who seemed homeless. Interestingly, all of these adults out panhandling on the streets were white.

Some older people, on Cuba’s very small pensions (as little as 150 pesos per month), earn money hawking newspapers, like Granma, Juventude Rebelde and Trabajadores. They buy papers at their cover price (20 centavos) and sell them to the public for 1 peso each. People understand they are helping their less fortunate neighbors this way.

Food

Some of the most basic commodities are heavily subsidized, and available to Cubans through government stores called bodegas. Most food must be purchased in outdoor markets and department stores, mixing state and private sales. The markets accept Cuban pesos or dollars while department stores or supermarkets (all publicly owned) only accept US dollars.

Produce at the outdoor markets is adequate but not attractively displayed. Selection is limited. You bring your own plastic bags, or you buy them from vendors at four for one peso. Meat (and there’s plenty of it these days, especially pork) is widely available. However, it was displayed both unrefrigerated and uncovered. Flies land and walk on the meat. I never got ill because it was fully cooked. I learned from experience to ask a nd sometimes show the butchers how to cut and trim the meat. If not, you might get bones smashed from the swift blow of a carelessly aimed cleaver, rather than neatly separated at the joint. Some butchers have a lackadaisical attitude toward this work.

nd sometimes show the butchers how to cut and trim the meat. If not, you might get bones smashed from the swift blow of a carelessly aimed cleaver, rather than neatly separated at the joint. Some butchers have a lackadaisical attitude toward this work.

Once a month there are massive outdoor sales of fresh food off of trucks which bring it in from the countryside. Prices are half of those in the regular markets. People put up with very long lines and inconvenience to stock up. The food is the same quality as in the regular agro-pecuarios. This shows that people have the capacity (that is, refrigerators and, in some cases, freezers) to store all of this food.

For most Cubans over age 40, having electricity and refrigerators at home remains something of a novelty. Lack of money and the inability to replace machinery require Cubans to find ways to keep things working. We’ve seen pictures of the ancient automobiles still plying Cuban streets. Where I stayed, the refrigerators were 40 or 50 years old or even older, and US-made. Besides having tiny freezer sections and needing frequent defrosting, these aged machines worked quite well. Indeed, when we tried to locate a new refrigerator for my hosts, they firmly insisted they’d keep the old one, and not discard it, if a new one was obtained. Cuba has begun to manufacture its own refrigerators, as well as selling Korean and other models. US brands like GE, by far the most expensive, were also on sale, though I didn’t find out if they were US-manufactured. The Cuban models are substantially cheaper, but they aren’t frost-free because that uses much more electricity. Cuban refrigerators I saw featured a distinctive design that allowed for a much more spacious freezer section than traditional models, and looked excellent.

Cubans seem to have an insatiable appetite for mayonnaise and sugar. Sandwiches are often made with just mayonnaise. I saw people eat it with a spoon! (I should talk: I eat peanut butter with a spoon...) Sugar is beyond popular. Massive amounts are used in tiny cups of coffee and even added to the sweetest of fruit juices.

Many workplaces provide food for their workers at heavily subsidized prices. The quality of the food can be discouraging. One day I ate lunch at a commissary, across the street from an office building. The meal, scrambled eggs with bits of ham and rice on the side, along with something which seemed soup-like, cost 50 centavos. (Remember: that equals 2.5 US cents!)

Workers who’d been there long enough to remember said that the food was quite good while the Soviet Union still existed. The alliance provided Cuba with a steady supply of much-needed commodities at stable prices. Cuba was able to limit to an extent the effects of fluctuations in the capitalist world market. The bottom line was that food was subsidized and cheaper for the Cuban population as a whole in those days.

Lunch was served in a plastic tray with separate compartments, no plates. We were given spoons, not knives and forks, and no napkins. It seemed more like an elementary school or a psychiatric hospital. One friend carries her own fork because she doesn’t like eating with a spoon. Late last year at times there was no food left when workers came for lunch. It was later discovered that commissary workers had been stealing the food and taking it home.

Considering the cost of a meat-based diet to a blockaded country, one might think (or at least hope) they would be open to alternatives to meat, but not yet. There is one vegetarian restaurant in Havana, at the national botanical gardens. Here, the cost was $10.00 USD for foreigners and 28 Cuban pesos ($1.40 USD!) for an all-you-can-eat smorgasbord. The meal was delicious, and completely vegan, not a speck of it animal-based. I asked one of the staff if she were a vegetarian and she said she was, and that the other staff members were beginning to get into it. This restaurant is linked to six other vegetarian places around the world, including one in Thailand called “Cabbages and Condoms!” On a second visit we were told there wasn’t enough food, so they offered all we could eat for half price. The four in my party were filled and satisfied.

Cuba will shortly open a soy processing plant in Santiago. Built in record time with a $27 million (USD) investment, its production is aimed at export to the Caribbean using the latest Swiss technology. Maybe it will find a market inside the island in time? However, people are slow to change tastes. Soy milk and soy yogurt were also offered for a time but are not popular. When I asked Cubans what food they really like, almost invariably the reply was—meat!

Who’s leaving Cuba?

Cubans who left in the earliest days of the Revolution are among the most hostile, and most supportive of the wealthy right wing of the Miami Cuban community, like the Cuban American National Foundation (CANF). They opposed the revolution politically, and many of them lost businesses and property. They refuse to visit Cuba (at least openly) and oppose normalizing relations.

Cubans who have left since 1980 are mainly economic emigrants. They hope to make a better life economically than they think they can in Cuba. They visit Cuba regularly and I met some. Some who left in 1980 have become supporters of the Revolution, after living in the US for more than a decade! I spent time with one of these emigrants, who returns to visit his family in Cuba at least once a year.

In 1996 Cuba and the US agreed on a lottery system which is supposed to permit 20,000 people to come to the US annually. This would be in addition to those who come illegally, and are admitted because of the Cuban Adjustment Act.

Some marry US citizens, often Cuban-Americans. I met two with unusual reasons for leaving. One was gay, the other a lesbian. Both got permission to leave by marrying Cuban-Americans. Neither expressed any hostility toward the Revolution. I met them through people who strongly support Cuba. They hoped to make better money abroad and, perhaps, to live more openly as homosexuals. (I’m guessing as they didn’t say this to me.)

people who strongly support Cuba. They hoped to make better money abroad and, perhaps, to live more openly as homosexuals. (I’m guessing as they didn’t say this to me.)

There are a few people from the US who live and work in Cuba, and have met and married Cubans. Though they must go through some red tape, and they paid a $1,000.00 fee, they all received approval. One has taken his Cuban wife and their Cuban-born son to and from the US. But this isn’t always easy. One friend didn’t get his final permissions for his vacation trip until literally hours before departure time.

Some Cubans who want to visit the US temporarily are denied permission by US immigration authorities on the grounds that they might stay in the US illegally. These same people had been told by the US Interests Section that they could get a permanent visa if they wanted to leave and not come back!

Tourism

Tourism is Cuba’s principal foreign exchange source. Old hotels and tourist facilities have been upgraded. New ones are being constructed in partnership with foreign firms. The effort has been very successful. Tourism has brought problems, too. Workers in other sectors are drawn toward tourism. I met people who had been teachers, but who felt compelled to work in tourism to make ends meet.

Others rent rooms in their homes or establish private restaurants, known as paladars (paladar is the Spanish word for “palate”). Those who rent rooms need a license from the state and are taxed heavily, $250.00 per month, if they’re in popular tourist areas, $200.00 in less-popular areas (and I think only $100 out in the provinces). They must pay the tax whether their rooms are occupied or not, so they are very eager to keep their rooms filled. You see signs posted outside and people passing out business cards with their information. They hustle!

By the way, the term “paladar” originated in a Brazilian soap opera. The female entrepreneur in the soap founded a restaurant called Paladar and the name stuck. There is also another Cuban term: cuentapropista, which means someone who works on his or her own account. It’s descriptive of all proto-capitalist activities, from family restaurants to private taxis.

Prostitution is a distressing reality. Its virtual elimination was a major early goal and gain in its first years. It reappeared in the 1990s due to economic recession and expanding tourism.

The young women engaging in this are not jailed, but the penal code has been changed to make procuring (pimping) a very serious offense. It’s easy (and sad) to see young women of school age but who are obviously not wearing school uniforms, and who have a universally recognizable appearance. I heard that the schools and universities are working together with psychologists, sociologists, the women’s federation, etc., to raise awareness around this. Of course, only improvement in the economy can reduce prostitution to its previous (1960s-1980s) almost non-existent level.

Hustlers and cops

Newspaper accounts of Cuban police in relation to tourism are mostly negative. I had a positive experience. My appearance and clothing (casual: jeans, polo shirt, T-shirts, etc.) and demeanor somehow made it obvious that I was a foreigner. (I laughingly told Cuban friends that I seemed to have an invisible poster across my chest with the word “Extranjero” [“Foreigner”] emblazoned on it.) I realized I was a magnet for some people whose interest in me was not necessarily friendly. Such people might have wanted something more tangible, like my money...

Walking home one evening, a young man struck up a conversation with me. His dress told me he was a hustler. He offered to introduce me to a nearby paladar, and to take me there, saying it was close. Always curious, and thinking I would just tag along, see about the restaurant, and learn a bit by listening to him, I followed.

He began complaining about how he’d been hassled by the police. When we got to the paladar, it was closed. Next he wanted to show me some other place. I declined. Then he said he just wanted to walk with me to Coppelia, the famous ice cream emporium about a block away. I said “no” again, but couldn’t shake him.

So I was pleased when a Cuban policeman came up and politely asked him for his identification (carnet). I kept walking, relieved that the officer had come along so I could go home. No, the guy wasn’t doing anything specifically, but the officer was protecting me (a tourist, a foreigner, someone unfamiliar with the lay of the land) from someone possibly after my money. The officer was also protecting me from my own naïveté.

The informal economy

Cubans are extremely resourceful. They have to have been to survive both 40 years of US blockade and the virtual collapse of their economy when the USSR disappeared. Private economic activity, licensed and unlicensed, has grown significantly. In addition to regular jobs in the peso and dollar sectors, need, scarcity and restrictions on private economic activity have generated a significant informal sector in economic life. The term “black market” isn’t used. The “informal sector” as an element in the economy is explicitly acknowledged.

Paying taxes is a new experience for Cubans in recent years. Some who leave jobs where they are paid with checks often prefer payment in cash so no paper trail is left. This way some hope to avoid paying taxes. Yes, this means there are now government inspectors whose job it is to try to catch people evading their taxes. Self-employed people must file an annual legal declaration regarding their income. As is the case everywhere else, there isn’t a lot of enthusiasm about paying taxes, but Cuban authorities say compliance with tax laws is high. This sounds rather hopeful.

Informal video rental seems widespread. Legally it’s done by state-owned businesses where typical rents are $1.00 USD per day. Through a system of informal video banks Cubans with VCRs are able to rent videos for 5 pesos (25 US cents) per night. Movies are obtained by people with satellite dishes. Bank owners could be fined or have their videos taken away if caught, but I heard no stories of that. I met one such entrepreneur who had hundreds of hand-labeled videos. His records were kept by hand in a notebook. His inventory was mostly Hollywood movies and no pornography. Unlicensed satellite dishes are a whole other issue. As in Iran, some people flout the law and there’s quite an informal commerce in sales, installation and configuration of the illegal satellite dishes.

Copying and selling pirated CDs also seems to be a big business. I met one man, manager of a beautiful, modern, air-conditioned bookstore with a staff, who also runs a side business copying CDs and selling them for $5.00 each. I don’t know what he pays for blank CDs, but if it’s anything like in the US, where they cost $1.00, his profit margin is considerable. He told me a European friend had given him the CD burner. Since burners can cost up to $300.00, this must be quite a friend indeed! I met a second man who also made money this way.

One of the beds where I stayed, which was built of wood, had begun to fall apart due to termite infestation. A local carpenter, who had been a math teacher until retirement, hand-constructed an entirely new bed out of bits and pieces of discarded wood he’d literally found. It became the most comfortable bed in the house. It cost $20.00 USD for time and materials.

Other examples of informal economic activity abound: street performance artists like an old man dancing to whom I gave a dollar, itinerant skilled workers like knife-sharpeners, and the peanut vendor who graciously allowed me to take her picture.

Internet access

Almost no Cubans have internet access at home. Cubans have had e-mail access and computer training for two decades through computer youth clubs and schools. They had to wait for a connection to the internet, which became available in October, 1996. This opened up the graphical world and instant delivery. They have had internet e-mail, both domestic (for more people) and international (for fewer people), for many years prior to 1996.

Only a few journalists, doctors and other scientists have e-mail at home. To check e-mail from elsewhere, foreigners have to use an internet café, such as the one at the Capitolio, where access is both slow and expensive at $5.00 an hour. You must present your passport, which is logged in at the desk, and Cubans can’t access the internet there. Students have net access at the University, but I wasn’t able to see under what conditions or limits.

Some Cubans have internet access at work. They are mostly people who work for foreign companies. Many Cubans have e-mail at their jobs, though without internet access. These limits are explained by the expense of the equipment (starting with computers), limited bandwidth and security considerations. The domestic Cuban intranet, however, has been built up over the last 20 years and is extensive. In a country where telephone service has been mostly unreliable, many businesses and universities use e-mail via the Cuban intranet to communicate.

A campaign that began in the Washington Post in December, 2000 claims that Cuba deliberately limits internet access to its citizens. It is hypocritical for the US, which does whatever it can to prevent Cuban access to technology, equipment and much else, to complain about this. Cuba is still a relatively poor Third World country. Its hard currency resources are kept for the highest priorities: health, education and self-preservation. Internet access is growing, but not as quickly as one would like. It’s far less widely available than in the US, where income rather than need is what decides.

All governments fear uncontrolled information. In the US, we are drowned with massive amounts of information. By this means, important information (like favorable materials about Cuba!) can be drowned out where not eliminated totally.

Anyone seriously concerned about expanding access to the internet in Cuba should speak out to end the blockade. If Cuba didn’t have to do so much to defend itself, and if Cuba were free to purchase computers and all the technology needed with it, internet access would be far more available there than it is at present. And Cubans might begin to purchase software that they currently cannot buy legally from US companies.

More importantly, when the internet is “opened” and made more available in Cuba, I can’t imagine it would ever be like it is in the US. There will not be 11 million people sitting alone at home at 11 million individual terminals. Remember, Cubans still share phone lines. That will continue, and so will sharing of internet resources. This is as much a cultural phenomenon as a resource-related one.

Cuba isn’t interested in giving everybody individual internet access. The whole society is more communal and collective than that. It is much more likely that, with unlimited access and resources just handed to them, Cubans would work out a community-based kind of access. CDRs and schools and community centers and clinics will be used for internet access, not each individual home. One beginning effort they are making is to put public terminals at post offices.

Living in the US where internet access is relatively inexpensive, I have a high-speed DSL connection, and I don’t pay attention to how long my computer stays connected. In Cuba, where access was $5.00 an hour for a slow connection at the Capitolio internet café, I had to carefully assess the value of what I was reading. Much and sometimes most of what I get in e-mail is junk, so I found myself deleting most of what I received in Cuba without reading it.

Cuba is willing to trade with anyone who will trade with it. I noticed that many of the computer monitors in the Capitolio, and elsewhere, were of Israeli manufacture. Cuba’s vigorous support for the Palestinians doesn’t keep it from having economic relations with Israel, which maintains a very low profile on the island.

World Solidarity Conference

Cuba hosts world gatherings of all kinds. Political meetings of solidarity activists, as well as medical, commercial and diplomatic gatherings occur constantly. I attended one, but others are held and reported all the time. More than 4,000 people from over 100 countries around the world came to express their direct solidarity with and support for the Cuban Revolution in November, 2000 at the Second World Solidarity Conference. They included members of left-wing political parties, trade unionists, students. Participants attended workshops and heard from top Cuban leaders, including economics chief and Vice President Carlos Lage, national assembly president Ricardo Alarcon, and president Fidel Castro.

Comprehensive reports were given on Cuba’s diplomatic standing, US efforts to reverse the 40-year-old revolution, and Cuba’s vigorous efforts to revive its economy. Their reports were published in Cuba, They were precise and objective, giving detailed and specific explanations, relying on facts and logic, not rhetoric. You can read Alarcon’s speech here.

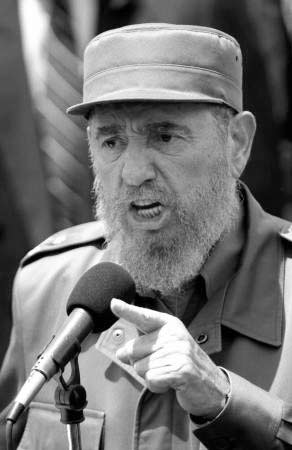

Carlos Lage and Fidel Castro took questions from the audience on a wide range of topics. Fidel, amazingly, took questions and answered for hours without interruption! While those on the platform sat and listened, and some in the audience (including myself) got up, walked around and came in and out of the hall, Fidel Castro stood there, without sitting down or taking a break, for the entire time, 5 hours!

Cuban diplomacy

Cuba has broken out of diplomatic isolation. When the Soviet Union and its Eastern European allies returned to capitalism, Cuba was shocked and isolated. It quickly recognized the new republics created after the USSR’s dissolution. In the 1960s, the US pressured all Latin American countries (except Mexico) to break relations with Cuba. Today every country in Latin America except El Salvador has relations with the island. These are expanding daily. (Even El Salvador has welcomed Cuban doctors, who are providing free medical aid after a recent disastrous earthquake.) Cuba now participates in Latin American summit conferences from which it had previously been excluded.

At the United Nations, Cuba has sponsored General Assembly resolutions opposed to the US blockade for many years. In the past many US allies, especially in Europe, voted with the US, but this has changed. In recent years even prominent US allies such as Britain have voted against the blockade, or have begun to abstain on these matters.

In the fall of 2000, only two countries voted with the US: Israel and the Marshall Islands (population: 68,000), a former US possession only independent since 1986.

At the 10th Ibero-American Summit in hosted by Panama in November, 2000, Fidel revealed that a band of Cuban terrorists, using false Salvadoran passports, were in Panama. They were plotting yet another attempt to assassinate the Cuban leader who was scheduled to speak at the university. Cuba provided the Panamanian authorities with needed documentation. Within two hours, the gang was rounded up.

The group’s leader, Luis Posada Carriles, has a well-documented history as a terrorist working for the overthrow of the Cuban government. He was charged for his role in the 1976 bombing of a Cubana airlines plane over Barbados. Seventy-three people, including the young members of Cuba’s Olympic fencing team, were killed. No one survived. Though arrested in Venezuela for his role in this atrocity, he mysteriously walked out of prison with the help of his counter-revolutionary Cuban associates. Cuba has requested the extradition of Posada Carriles and his associates from Panama. The Panamian government sent mixed signals as to whether or not it will grant Cuba’s request. Although Cuba retains the death penalty and Panama does not, Cuba has publicly declared it would not apply the death penalty in Posada’s case. As of May, 2001 Panama has announced it will not extradict any of the gang.

Venezuela’s growing friendship with Cuba under President Hugo Chavez, a left-wing nationalist, is very significant. An entire section of the Jose Marti museum at the Plaza of the Revolution in Havana is devoted to Fidel’s fall 2000 visit to Venezuela.

Cuban doctors have been caring for patients in Venezuela, and Venezuelans with unusual medical problems have been brought to Cuba for specialized care. Fidel addressed a special session of the Venezuelan legislature. When a few right-wingers complained, Fidel took up the points they raised and answered them. He made a detailed and eloquent presentation. You can read Fidel’s speech here.

In Mexico, Fidel was an honored visitor during the inauguration of Vicente Fox, Mexico’s first post-PRI president. Mexico is revitalizing relations with Cuba. The capitol’s first female mayor, Rosario Robles, a member of the Democratic Revolutionary Party, presented the Cuban leader with the keys to the city. He also met with leaders of the Roman Catholic hierarchy who publicly spoke out against the blockade, something their Cuban counterparts have never done.

Fox appointed Jorge Castaneda his foreign minister. Castaneda wrote an unsympathetic biography of Che Guevara. Mexico’s new ambassador to Cuba, on the other hand, is Ricardo Pascoe, a long-time left-winger.

I met Pascoe many years ago when he was a member of a small revolutionary left-wing political party. I was a member of a similar party in the US. (That’s how we came to meet.) Like many others on the left, Pascoe joined the PRD, established by Cauhetemoc Cardenas after he left the Institutional Revolutionary Party, Mexico’s former ruling party. So deep is Mexican opposition to the US blockade that even Vicente Fox’s right-of-center National Action Party (PAN) participates in the Mexican movement of solidarity with Cuba!

After the fall of the Soviet Union, during the presidency of Boris Yeltsin, Cuba’s relations with Russia soured. At the end of 2000, Cuba welcomed visiting Russian president Vladimir Putin. Both sides stressed their historic ties dating back to the days of the Soviet Union. Expanded economic and other activities were publicized, but few details were released.

Cuba also announced during the Putin visit that it would not complete the Juragua nuclear power plant in Cienfuegos, which the USSR helped to construct. The Juragua plant was something the United States had made a big stink about. (This from the nation which gave us Hiroshima, Nagasaki and Three Mile Island.) For its own reasons, Cuba refused for years to publicly declare the nuclear plant project dead. So it became a big US media flap, and the US used it as an excuse to install “radiation sniffing” devices aimed at Cuba. More likely, they were devices to eavesdrop on Cuban communications. The US, which had complained so bitterly about the nuke plant when it was announced, was oddly silent about the decision to abandon it. However, this decision was in line with many other environmentally sensible things Cuba has initiated since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Part Three will follow in November.

Erratum: Credit for the front cover photograph of the September issue, Volume 1, number 4, should have been given to Walter Lippmann.

Write us!

socialistviewpoint@pacbell.net