![]()

Write us!

socialistviewpoint@pacbell.net

God Should Have Known Better

By Larry Wilson, Appalachian Focus

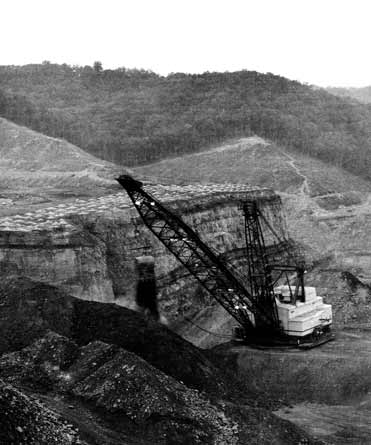

On October 11, 2000 one of, if not the largest, environmental disaster in the history of North America occurred deep within the Appalachian Mountains of Eastern Kentucky (USA). This happened when a coal waste impoundment, owned and operated by Martin County Coal Co. (owned by A.T. Massey Coal Co. which is owned in turn by the Fluor Corporation) broke into abandoned underground mines and spilled in excess of 750 million gallons of coal slurry into nearby streams and rivers. Even though it was many times greater that the infamous Exxon Valdez disaster, and directly affected many towns and villages, the mainstream media, national environmental organizations, and political entities paid little or no attention. Why?

The Central Appalachian coalfields

The Coalfields of the Central Appalachian Mountains include portions of the U.S. states of Kentucky, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Virginia and the entirety of West Virginia. Within this region is concentrated some of the world’s richest natural resources. Coal, oil, gas, water and timber are abundant. Also within this region reside some of the nation’s poorest people.

This region came to national attention in the 1960’s because of the degree and extent of poverty there. Little relief has come to the people of the region since the infamous “War on Poverty.” At that time one in three persons in the Appalachian coalfields lived in poverty—50% higher than the national average. Currently the poverty rate is 49% higher than the national average. Presently, the high school completion rate is only 51%. Other statistics are similar.

There are several reasons for this disparity. First, the region has been artificially divided in ways that divide and separate the residents of the area from one another. These barriers have been very effective in prohibiting collective organizing and action. Perhaps the most effective barriers are simply state lines. This relatively small area is in portions of six states, resulting in different agency structure, laws, contact points, etc. Central Appalachia falls within three separate regions of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (US-EPA), which complicates environmental permitting and enforcement. All of this is in spite of the fact that the residents of the Central Appalachians share a rich and unique culture, a common single industry dominance (coal) that shapes the economic and political scene, a more or less common ancestry, and a common history of independence and strong family values.

A second reason for the socioeconomic woes is the stereotyping which has been internalized by some of the residents to the point that many believe that the only way to escape their plight is to leave the region and/or deny and erase their culture and heritage. Gallons of ink and reams of paper have been consumed writing about the “quaint” people of the Central Appalachians. Within mainstream American society, ethnic and racial jokes and stereotypes are no longer permissible—with one exception. Television series such as “The Dukes of Hazzard,” “Beverly Hillbillies,” and “Green Acres;” cartoons like “Snuffy Smith;” and the movie “Deliverance” still thrive. In order to expedite the extraction of resources, the people too must be exploited. In order to make this acceptable, they are dehumanized and made to appear “different” from the rest of the nation in a way that validates their exploitation.

Disaster strikes

The October 11th spill began when an underground coal mine collapsed and the contents of a 72-acre “pond” containing coal slurry approximately the thickness of wet cement poured from the “pond” into the mines and gushed out two openings into nearby Coldwater Fork and Wolf Creeks. The slurry then made its way into the Tug Fork river and on to the Big Sandy River. It eventually emptied into the Ohio River near Ashland, Kentucky.

The spill was so devastating that Kentucky Governor Paul Patton was forced to declare a state of emergency for ten counties. The spill forced the cities of Inez, Kentucky; Louisa, Kentucky and Kermit, West Virginia to close water intakes and rely on supplies provided by trucks and temporary pipelines operated by the national guard and citizen volunteers.

Martin County schools were canceled for one month. Restaurants, stores, and businesses were forced to close their doors. Many residents were forced to evacuate their homes and seek temporary shelter wherever it could be found.

This is an area that relies heavily on underground aquifers as a source for potable water. These private wells and springs are no longer usable by residents.

Now, several months after the original incident, the adverse effects are very prominent among the residents of the region.

•Many residents have red blotches, called “sludge bumps” by neighborhood children, spread across their bodies.

•Those who have dared to blame the coal company or file suits for property and health damages are subjected to harassing phone calls.

•There are telltale black rings on trees where the sludge reached its peak and the spill has left similar scars on the people whose lives were disrupted.

•Roads and bridges were rendered impassable and remain insufficient.

•One can throw rocks in the creek and watch as a plume of black follows the impact.

•One resident’s backyard still looks like a reclaimed strip mine site, very poor quality rocky soil and a thin cover of grass growing in little bits and pieces. There were still some bald spots in the yard. The yard is still rippled with the treads of bulldozers and heavy equipment.

•According to the U.S. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) analysis, “in some samples of the source coal slurry material, copper, vanadium, manganese, barium, arsenic, and cobalt were above levels of health concern”. The report also indicated a slightly elevated level of copper in the raw (untreated) water at the Martin County Water Plant in Inez. The report also states “in some forms, barium, arsenic, and vanadium can produce health effects by skin contact. In most cases, these effects can occur after prolonged exposure lasting a year or more. Like most heavy metals, all of these compounds effect the digestive system, the kidneys (except manganese), and the liver (except vanadium). Many of these compounds produce effects on the central nervous system and some of them produce effects on the cardiovascular system”. Arsenic, cobalt and barium can also produce swelling of the eyes. The concentration of arsenic found in the slurry can also cause skin irritation. Exposure to high levels of cobalt can also lead to skin rash.

•There is still a considerable amount of sludge left in the “reclaimed” backyards and the creeks.

•At Wolf Creek, the creek that got mostly watery slurry, it appears that the cleanup operation there is finally over. The hydro-mulch and the heavy equipment are mostly gone, and all along the denuded creek banks there is a swath of bright new green grass and a few weeds, but little other plant life in many stretches. There are thousands of new stumps along the creek where the riparian vegetation has been removed for the cleanup operation, and the creek bed is full of silt. Basically Wolf Creek will just be a muddy trench baking in the sun for the next ten or fifteen years until the trees can grow back.

•Although the large blobs of sludge are gone, there is still a lot of black silt in the creek bed and along the banks. Martin County Coal has installed black plastic fences about 18 inches high along both sides of Wolf and Coldwater Creeks to reduce the amount of soil erosion, but this seems kind of absurd and ironic in light of the amount of silt already in the creek, and the level of damage that has already been done to the creek by the spill and the cleanup operation.

Responses

Martin County Coal initially refused to respond to questions about the spill. They simply provide a news release that blamed the spill on a “sudden and unexpected” collapse of the underground mine roof. They place company guards on the state highway leading to the site of the disaster and refused entry to any one, with the exception of regulators and one company led group of news reporters. Regulatory agencies would simply state that the cause of the disaster was “being investigated”. Industry officials were silent.

However, as the magnitude and effects of the disaster became publicly known, silence and simplistic statements were no longer acceptable. The public demanded actions.

Kentucky Department for Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement issued four notices of noncompliance to Martin County Coal for violations. They accused the company of “engaging in an unsafe practice by allowing substandard water and slurry” to flow from the impoundment into the underground and creating an “imminent environmental damage.”

Martin County Coal was ordered to “immediately cease all substandard discharges” and “...re-establish access to all driveways and any county and state roads blocked by slurry.” They were also ordered to replace all fish and other aquatic life killed and to rebuild roads and bridges damaged by the spill.

Governor Paul Patton of Kentucky declared a state of emergency for 10 Kentucky counties stating the spill was, “endangering the public health and safety, and could result in potential environmental damages.”

Martin County Coal began dredging the slurry from streams and placing it in newly constructed temporary “ponds” on top of a nearby mountain. The company also sent two tractor-trailers filled with gallon jugs of water to the town of Louisa, Kentucky. They also obeyed an order from the state and removed their armed guards from the state highway allowing public access leading to the site of the spill.

The Unified Command (State Federal Agencies dealing with the disaster) admitted that the Martin County Coal Company’s president edited news releases issued by them. They agreed to cease that practice.

Martin County Coal’s president Dennis Hatfield met at least four times with members of the effected communities and promised that the company would “...get it back to normal.” He publicly apologized for the incident saying, “We very much regret that this has happened. It is a mess. It’s a disaster. And we’re just trying our best to get things back to normal. We’ve made mistakes,” Hatfield said, “I’d be the first to admit that. We’ve messed up a bunch of times.”

However, two months later, in response to five civil lawsuits for damages against Martin County Coal, the company made two defenses claiming:

•That the slurry spill “was the direct, sole and proximate result of an act of God, the occurrence of which was not within the control of Martin County Coal”, and;

•That any alleged negligence by the company occurred more than five years before the October 24, 2000 filing date of the suits and therefore is barred by statutes of limitation.

The U.S. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (the same Agency that would later acknowledge hazardous levels of chemicals in the slurry) met with residents and assured that there was no health hazards. One resident was quick to point out that each member of the state and federal experts assembled to make the statement, had bottled water in front of them.

Coal slurry “ponds”

Coal slurry is a thick mix of water, coal waste, rock and chemical used to “clean” the coal. It contains many heavy metals such as arsenic, mercury and lead, but is not classified by the state and federal governments as hazardous since it is supposedly not buried in landfills nor discharged into public waters. Extremely large amounts of slurry are produced in the processing of coal prior to shipping. Coal companies dispose of the slurry by pouring it into huge impoundments built behind dams made of bigger chunks of preparation plant waste or by injecting it into old, abandoned underground mines. Over time, solids in the slurry settle to the bottom and the liquid remaining on top is discharged into the nearest stream.

Today there are an estimated 1,000 such slurry ponds scattered throughout the coalfields. The largest concentration of these is in the Appalachian Mountains of West Virginia and Eastern Kentucky.

History

The history of coal waste impoundments is not a good one. In 1972, a slurry dam operated by Pittston Coal on Buffalo Creek in Logan County, West Virginia collapsed. Flooding killed 125 people and destroyed 500 homes.

In 1981, a similar dam in Harlan County, Kentucky broke killing one person and destroying much of the community of Ages.

In 1996, a CONSOL Energy coal waste dam at the company’s Buchanan No. 1 Mine near Oakwood, Virginia leaked into old underground mine workings and blew out the other side of the mountain. Coal slurry gushed into a tributary of the Levisa Fork of the Big Sandy River at a rate of up to 1,000 gallons per minute. The 25-mile spill blackened creeks and killed fish.

Also in 1996, an Arch Mineral Corp. impoundment in Lee County, Virginia broke with similar results.

A.T. Massey Coal’s track record is less than spectacular. In 1994, Martin County Coal was fined for a similar collapse that spilled blackwater—”in amounts too great to be measured”—into area streams. Since 1986, the company has been fined for nine separate spills from sediment ponds and waste impoundments. In West Virginia, Massey subsidiaries have been repeatedly cited by state and federal regulators for spills from their mining operations along the Coal River in Boone and Raleigh counties. USEPA recently settled spill cases against Massey subsidiaries Elk Run Coal Company and Goals Coal Company.

It should not have come as a surprise that this particular structure failed. Three years ago, U.S. federal Mine Safety and Health Administration investigators inspected the Martin County Coal Corporation dam. They found that a manmade barrier between the impoundment and underground mine works may not have been designed to withstand water pressure from the slurry. They concluded that a breakthrough at the impoundment could endanger miners and public safety.

In 1994 a federal engineer investigating yet another coal slurry spill from a Martin County Coal impoundment warned that seals separating the impoundment’s floor from an underground mine were inadequate. In that same year, another engineer with the Mine Safety and Health Administration warned that area mine maps, used to gain approval of the structure “appear to be inaccurate. Therefore, a very conservative design is warranted. If the water in the impoundment broke through, it is very possible that they would fail and a loss of life could occur. In spite of this, Martin County Coal was permitted to expand the impoundment later in 1994.

A veteran mine-safety expert resigned from the federal team investigating the disaster because of his belief that the group’s final report will be a whitewash. A mining engineer with 35 years experience in mine safety said in a letter, “I do not believe the accident investigation report, as it is now being developed, will offer complete and objective analysis of the accident and its causes.”

Bill Caylor, president of the Kentucky Coal Association, an industry group of coal-mining companies responded to citizen’s allegations of property damage and health effects by stating, “Martin County Coal is a good company with a good reputation. This is a way for residents to get their property bought in an economically depressed market. They are smelling home cooking on a local jury.” He responded to a suggestion that such impoundments be banned by saying, “Banning coal impoundments would eliminate mining. If you can’t dispose of coal economically, you can’t sell your product.”

Summary

To think that there are approximately 1,000 of these impoundments tucked away in the mountains of Central Appalachia is frightening. They have a long history of failing. The agencies whose duty is to regulate these and protect the public and the environment has a long history of protecting the companies instead. The news media whose duty it is to expose these have a long history of ignoring such events in this region (one paper actually reported that it was fortunate that this event occurred in an “uninhabited area”). The people are economically and politically powerless.

These events will continue to occur and worsen until the rest of this nation refuses to accept the exploitation of the people whose only offense is to be born in a region rich in culture and history, but poor in power and money. I don’t think that will happen because those who could help us bring about change would rather see us die than to give up their inexpensive energy sources.

And after all, God should know better.

Printed with permission from:

The Loka Institute

P.O. Box 355, Amherst, MA 01004

E-mail: Loka@Loka.org

Web: www.Loka.org

Write us!

socialistviewpoint@pacbell.net