![]()

Write us!

socialistviewpoint@pacbell.net

|

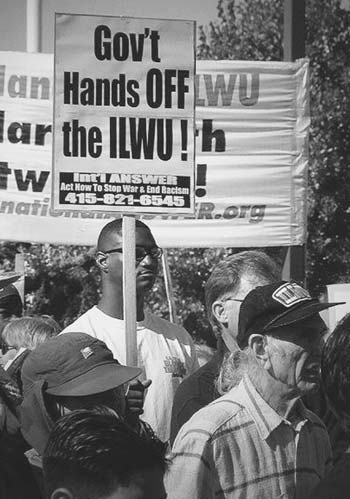

| One of the more than 10,500 union longshore workers locked out of their jobs by the Pacific Maritime Association (PMA) since September 27, 2002. Earl Fritts, a member of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) Local 19, pickets in front of a locked gate as hundreds of cargo containers sit idle at Terminal 46, at the Port of Seattle, Washington, October 2, 2002. Photo by Anthony Bolante/Reuters |

Though the Taft-Hartley Act has been on the books for over five decades, it has never been used to end an employer-led lockout. Never that is until Tuesday, Oct. 8, when the Bush administration came down hard on the bosses’ side in the contentious West Coast contract dispute over jobs and the future of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU). Heeding the government’s plea, a federal judge quickly forced an end to the 11-day lockout, engineered by the Pacific Maritime Assn. (a consortium of shipping and terminal bosses) to spur government intervention. A union spokesperson told the San Francisco Chronicle that the bosses and the feds had devised “a carefully coordinated campaign to develop a crisis to neutralize the union’s bargaining position.”

That view was partly backed up by William B. Gould IV, a former chairman of the National Labor Relations Board, who told a Los Angeles Times reporter that “the lockout is a tactic aimed at bringing in the Bush administration through Taft-Hartley.” And Nelson Lichtenstein, a labor historian, told the San Francisco Chronicle (Sept. 29), that the bosses’ lockout was “just a trial balloon. Both sides are engaged in a high stakes game, with the ILWU trying to win public support and the PMA wanting the Bush administration to step in.” A prominent Democrat, Sen. Diane Feinstein, joined the conflict when she called for President Bush to impose the Taft -Hartley Act, should the lockout last more than a week.

But much earlier, the union said that forcing the dockworkers back to work would not resolve the dispute. The union said that the dockworkers had been forced to work under the Taft-Hartley Act in 1971, and struck again as soon as the so-called cooling-off period was over.

The bosses said their lockout was provoked by a work slowdown that greatly reduced productivity. The union adamantly denied it had orchestrated a slowdown, but it also said: “The ILWU Negotiating Committee passed a resolution today, Sept. 26, calling on members to redouble efforts to improve safety on the docks. The resolution, distributed to all locals, calls on longshore workers to follow all safety procedures, including speed limits, to refrain from working extended shifts, working through lunch hours, or doubling back. It also calls on ILWU members to ensure that all military sustainment (sic) cargo is handled without any difficulties or delay.”

If productivity on the docks doesn’t quickly return to pre-lockout levels, the shipping and terminal bosses undoubtedly will call on the government to take action, perhaps assigning military crane operators to replace union workers. The Clinton-appointed judge who ordered the workers back to their jobs warned, “The lockout is over as of now and … the union is ordered not to engage in any slowdowns. I want to make it clear, you are expected to immediately resume normal operations.”

The workers will return to the docks, but that doesn’t mean that their fight with the bosses is suspended for 80 days. According to the Oakland Tribune (Oct. 9), “Union leaders remained defiant Tuesday, saying they will not compromise safety to increase production…” The union says that there were five deaths on the docks this year, and five deaths are five too many! It seems a safe bet that the bosses’ intransigence at the bargaining table will be dramatically tested on the docks sooner rather than later.

In October 1960, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union signed a watershed contract that radically altered work practices on the West Coast docks. Over time, more and more mechanization and containerization took place; and the union grew smaller. Though individual dockworkers saw improved wages and benefits, at least part of the improvement was paid by lost jobs, not profits.

In 1971, a federal pay board estimated that dockworkers’ productivity increased by almost 140% in the previous ten years, as contrasted with a national increase of 30%. During that time the bosses paid the dockworkers $62 million for their increased productivity, but pocketed $900 million in saved labor costs.

Once again, the shipping and terminal bosses are looking for increased productivity; if the bosses are even partially successful, the ILWU membership base on the West Coast docks will continue to shrivel. In the current negotiations the ILWU bargainers have already agreed to give up an estimated 600 clerks’ jobs; as a quid pro quo the ILWU wants the bosses to recognize the union’s jurisdiction over new jobs, created as more mechanization and computerization is introduced.

Should the union fail to win its jurisdictional claim over the prospective computer-related jobs, its traditional power to affect productivity will surely fade, as employers introduce more technology at the docks and conduct more technological operations away from the docks. An expert on port operations told the New York Times (Oct. 2), “This dispute is not just about money, it’s also about control.” With only 10,500 dock jobs left, the ranks have to wonder how many more jobs the union can lose without losing its control over the chokepoints of the West Coast shipping business.

If there is no settlement by the end of 80 days, the union is likely to call a strike. But once again the government may intervene on the bosses’ side. Shortly before the union agreed to a new contract in 1971, the Nixon administration and the Democratic Party-controlled Congress decided to impose compulsory arbitration and bar a strike for 18 months. A last-minute settlement allowed the union to escape compulsory arbitration, but the ranks were robbed when the government Pay Board voted 8-5 to cut wage and benefit increases from 25.9% to 14.9 %. In protest, four labor members of the Pay Board resigned; the Teamsters president, Frank Fitzimmons, stayed on. Before the Pay Board’s stinging decision, Harry Bridges, the ILWU president, vowed to fight if even one cent was cut from the settlement; but then he thought better of it and the dispute ended.

If the 1971 events and their resolution are any guide, the ranks need additional power to maintain, let alone improve, their present relationship of forces against the bosses and their political allies. At least some of the ranks believe that they have an ace in the hole; they’re counting on the solidarity of dockworkers around the world. Surely, the refusal of those dockworkers to unload ships from the U.S. would be a powerful weapon. But a widespread dockers’ boycott of U.S.-loaded ships would be unprecedented.

On Sept. 30, the ILWU’s president, James Spinosa, said that the bosses had offered to buy out the workforce. “That position,” he said, “is totally unacceptable to the ILWU; we will not move along those lines, not now, not ever in the future. What we are looking for in this set of bargaining are jobs, jobs that remain in the industry, jobs that are ours under the contract and the Employers have got to step up to the table, if they want to see those West Coast ports resume their activities like they have in the past.”

Write us

socialistviewpoint@pacbell.net