Fantham and Machover’s Tableau Economique (Fantham and Machover, p. 10)

Colin Barker Archive | ETOL Main Page

Theories of Russia

The second group of theorists who recognise that Russia is a class society take a very different position from that of Bettelheim. They recognise that there is, effectively, no dominant market relation within Russia, that the economy is a highly centralised, administered economy, ruled by a bureaucratically organised class. Without exception, they also differentiate themselves from the position developed in the 1930s by Trotsky: they do not see in the existence of state property or ‘planning’ an element of socialism but a particular form of class oppression and exploitation. They also reject the idea that Russia is in any other sense capitalist.

The theorists in this group are of especial interest, for a number of them are dissident East European intellectuals, some of whom have been persecuted for publishing their critiques of the political and social systems in their countries. Svetozar Stojanovic and others of his colleagues round the Yugoslav journal Praxis have been deprived of their university posts; Rudolf Bahro was imprisoned for publishing his book in West Germany; Kuron and Modzelewski were gaoled for publishing their Open Letter to the Party, and are now once again in danger from the Polish regime for their activities around KOR, the Committee for the Defence of Workers; others with similar views in Hungary and Czechoslovakia have also been removed from their posts, or are now in exile in the West. [77]

The arguments these writers propose have also been taken up, with some variations, by writers in the West, including Ticktin, Fantham and Machover, Carlo and Melotti. [78]

Some of these writers appear aware, others not, that their ideas were, in a sense, prefigured in the writings of dissident members of the Fourth International at the end of the 1930s, in particular Max Shachtman and James Burnham. [79]

Space does not permit a full treatment of the ideas of each of these writers. I shall focus on a a number of common themes in their arguments, illustrating the themes with quotations from them where it seems appropriate. It would be a mistake, however, to think that they are in total agreement with each other, and where it seems useful I shall point to differences between them.

For number of these writers, the starting point of their analysis is a comparison between the ideals of revolutionary Marxism, as they are still (to some degree, and in a more or less perverted fashion) preached by the rulers of Russia etc., and the reality of life in these societies. On every possible measure, the critics declare that the gap between ideal and reality is enormous. In the circumstances of political life in these countries, Marxism itself has been massively transformed as part of the process of the degeneration of the revolutions, Thus, for instance, Stojanovic (p. 8):

‘The transformation of Marxism from revolutionary critique to the conservative-apologetic ideology of the new ruling class proceeded parallel with the oligarchic-statist degeneration of the communist party and the revolution.’

Rather in the manner of Bettelheim and others, Stojanovic sees the key to this theoretical degeneration as lying in the view taken of the task of a socialist revolution. For Stalinism what matters are changes in the spheres of ‘material and cultural construction’ rather than in social relationships themselves. The Stalinists recognise no structural or other contradictions in the new form of society; if there are ‘problems’, these are the result of ‘hangovers’ from the pre-revolutionary period. ‘The humaneness of productive and other relations among people was the criterion of social progress for Marx’, but for the present-day rulers of these societies the basic measure becomes the development of the forces of production, understood statistically, in terms of increased rates and quantities of output.

For many of these writers, Marx’s concept of ‘alienation’ provides them with their key entry point into the critique of Stalinism and post-Stalinism. The standpoint from which they assess these actual societies is that of socialist or communist society in Marx’s sense; from this standpoint they find what Bahro terms ‘actually existing socialism’ totally wanting. All of he East European writers, in greater or lesser measure, demonstrate that they have been greatly influenced by the early writings of Marx, many of which have only been published in the last couple of decades. Marx’s Economic and Economic Manuscripts of 1844 have proved to be a brilliant source of inspiration to the dissident communists of Eastern Europe. Indeed, the larger part of the work of the Praxis group in Belgrade has been devoted to the elucidation of these early writings, and their significance for a revival of genuine Marxist thinking.

What the history of the twentieth century has shown clearly is that alienation is not simply linked to the institution of private property in the narrow legalistic sense. It is quite as much a characteristic of societies like Russia in which private property has been largely abolished:

‘It has turned out that the place of private property can be taken not only by social property, but also by a new form of class property – statist property, and along with it a new form of economic-political alienation no longer in socialism, but rather in statism.’ (Stojanovic, p. ?)

The application of this argument leads to a quite unambiguous conclusion:

‘The most prominent ... ideological-political myth of our age, is the statist myth of socialism ... With the degeneration of the October Revolution a new exploitative class system was created, a system which stubbornly tries to pass itself off as socialism.’ (p. 3?)

What we are dealing with, Stojanovic insists, is not any transitional form of society, which might be termed ‘state socialism’, where the state and nationalised property represent an initial and indirect form of social ownership, where state property is held through the representatives of the working class and in the interests of the working class, The system in Russia and elsewhere is one where a bureaucratic state is master of society, disposing of ownership in its own interests.

Stalinist state ownership is collective ownership on the part of the bureaucratic state apparatus. It is a new form of class society, for which Stojanovic proposes the term ‘statism’. Many of the same ideas also appear in the work of Rudolf Bahro. Like Stojanovic, he centres his analysis on alienation, a phenomenon arming, he emphasises, in the context of the division of labour – and in particular the division of mental and manual labour. It is this division, Bahro suggests, which is the common feature of all class societies, and which provides him with the basic starting point for his critique of social relations in Russia and other countries of ‘actually existing socialism’. Like Stojanovic, Bahro declares that these are class societies, and he draws extensively on the Idea of ‘the Asiatic mode production’ to argue the relevance of this perspective.

Rakovski rejects taking ‘alienation’ as a starting point, but comes to conclusions similar nonetheless to those of Stojanovic and Bahro. Russia and the other East European countries are examples of

‘a modern non-transitional society where there is no capitalist private property but where the means of production are not at the collective disposal of the producers; where there is no bourgeoisie or proletariat but the population is still divided into classes; where economic priorities are not normally determined by the market, hut neither are they chosen by means of rational discussion among the associated producers, and so on. (Rakovski, p. 15)

‘Soviet-type societies’, he concludes, ‘are sui generis class societies existing alongside capitalism.’ (p. 17)

Some of these writers limit their discussion to Russia and the satellite countries in Eastern Europe. Others, however, extend the discussion to other backward countries. They suggests that the kind of structure that emerged initially in Russia represents, in effect, a new ‘mode of production’ quite different from capitalism through which backward countries have found a new road to industrialisation. Thus, for example, Bahro:

‘The Russian revolution showed that these peoples (of the colonial and semi-colonial countries, CB) could not escape their pariah role simply by political and military liberation struggles and revolutions. The specific task of these revolutions is the restructuring of the pre-capitalist countries for their own road to industrialisation, the non-capitalist one that involves a different social formation from that of the European road.’ (p. 126)

The following of the non-capitalist road requires a particular kind of social and political mobilisation for the ‘forced march’ to industrialization – where industrialization is the precondition for the participation by those nations in the gathering of the fruits of the modern world:

‘... only those nations whose history, and the immensity of their demand gives them the capacity to organise themselves for the forced march into the modern era, have a prospect of maintaining their identity and bringing the treasures of their cultural tradition into that global human culture that is already in the process of arising.’ (p. 128)

The role of the state in this different industrialisation process is crucial. Drawing on various remarks by Engels and Marx, Bahro suggests that the state is more, much more, than merely an instrument of class repression – although it is that too. The state – as can be seen from the example of the Asiatic mode of production – is also the organiser, the ‘taskmaster of society in its technical and social modernisation (p. 129). For Bahro, as for Fantham and Machover, what is at issue is not just Russia or the other countries that call themselves ‘socialist’. The state plays this mobilising, taskmaster role in net just the USSR or China, but also in Burma, Algeria, Peru, Zaire – and

‘even Iran, where a Shah stemming from an era before classical antiquity is conducting his own “white revolution” – this only underlines the fundamental value of the state in this context.’ (p. 129)

Similarly, Carlo argues that the idea of ‘bureaucratic collectivism’ is applicable not just to Russia, but also to Egypt. (Fantham and Machover, while accepting the general drift of the argument, disagree over the examples of Egypt and Iran, which they regard as ‘capitalist’. On the other hand, Fantham and Machover treat China as an example of ‘state collectivism’, while Carlo does not.)

Several of these writers suggest that their theories have significant implications for Marxist historical theory generally. In particular, they reject the idea, propounded most strongly by Stalinist versions of historical materialism, that there is an invariant succession of ‘modes of production’ through which every society must pass. Bahro refers to the notion, much favoured by Russian propagandists, of the ‘regular succession of five formations: primitive communism, slavery, feudalism, capitalism, socialism-communism.’ Such a simple, unilinear scheme could only be imposed on historical development at the cost of massive distortion (pp. 61ff.). Similarly Rakovski:

‘Within the traditional structure of historical materialism there is no place for a modern social system which has an evolutionary trajectory other than capitalism and which is not simply an earlier or later stage along the same route.’ (p. 17)

And Fantham and Machover, generalising rather more, suggest that what has occurred has been what they term a ‘bifurcation’ in human history:

‘A series of societies in the under-developed world have branched off into a non-capitalist path, a path which runs not between capitalism and socialism, but parallel to capitalism; a path along which these societies can industrialise and to some extent catch up with the more advanced parts of the world.’ (p. 4)

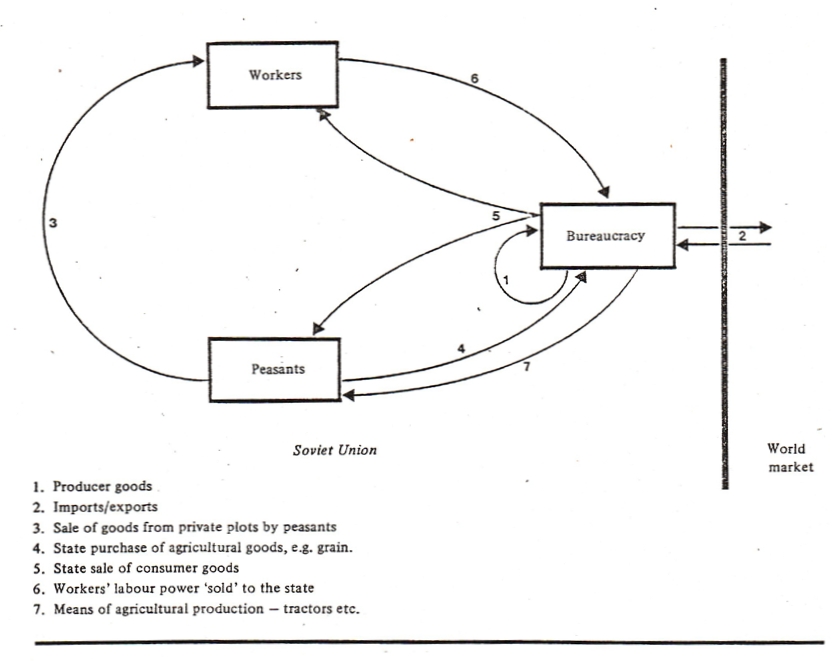

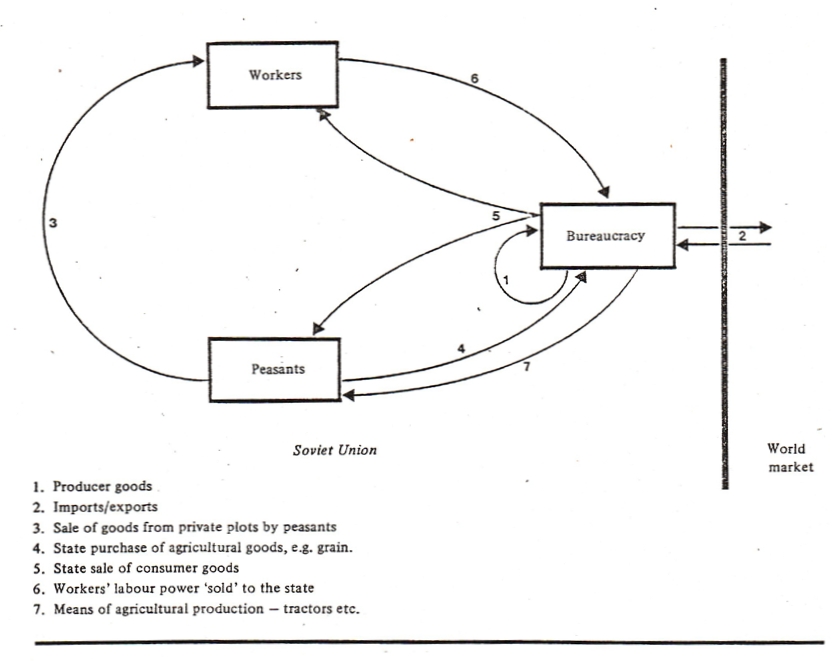

Fantham and Machover illustrate what they argue is the fundamental structure of these ‘state collectivist’ societies, existing parallel to capitalism, with a Tableau Economique (reproduced below) illustrating the major economic flows within the system.

|

|

Fantham and Machover’s Tableau Economique (Fantham and Machover, p. 10) |

Of the seven categories of ‘flow’ they list, only 2 and 3 – imports and exports to the world market, and the of goods by peasants from their private plots – are commodity exchanges. As for the others:

Thus, ‘in the USSR capitalism exists, if at all, only as a residual element and as a subordinate mode of production at the margins society.’ (p. 10) The same model can be applied to other ‘state collectivist’ societies.

These writers tend not to develop their account of the economic functioning of the Russian and other similar societies, or to do so rather differently. Carlo emphasises the enormous stress placed, in practice, on the development of what Marx called ‘Department I’ industries – industries producing, not means of consumption, but means of production. Ticktin focuses rather on the massive extent of ‘waste’ production; the tendency to produce goods that no one wants, the low quality of goods produced, the difficulties experienced in those societies with technological innovation etc.

There is a partly explicit, partly implicit account of the development process in these writers’ work. In this account, these systems are ‘progressive’ in the early stages of their development, but the highly bureaucratised economic mechanism becomes increasingly an impediment to further development. These national economies tend to run into various kinds of limits to development, which can only be solved through more or less radical re-structuring of their entire economic and political mechanisms. Some of the authors look forward to a socialist revolution, others suggest that two options for the future exist: a socialist revolution or a capitalist one. The latter possibility – a capitalist re-organisation of the these countries – is possibly inscribed in the tentative development towards market-type ‘economic reform’ of the kind associated with writers like Ota Sik in Czechoslovakia, Liberman in Russia, or Brus in Poland.

The broad thesis concerning economic development is, however, clear: these societies are ‘progressive’ in their youthful stages, and a barrier to development in their later stages. Thus Fantham and Machover suggest that China may be still in its ‘progressive’ phase, while Russia is not. (Presumably Russia’s ‘progressive’ phase occurred at the height of the Stalin period, when the forces of production grew most rapidly.)

Some writers in this school look definitely to the revolutionary overthrow of this system of social relations by the working class; others are either less loss clear or assume a more reformist or evolutionary path of development.

Some of these writers use the terminology associated with the capitalist mode of production to describe social and economic phenomena, others suggest that this terminology is inappropriate. Ticktin, Fantham and Machover and others, for example, use the term ‘working class’ in an unqualified way. Carlo on the other hand, suggests that the term may be strictly in appropriate, since his argument is that the Soviet worker produces surplus-product but not surplus-value, and is not involved, strictly, in a ‘wage-relation’ with the single ‘employer’, the State.

‘Technically speaking, a new term should be used. But since what is important is the content and not so much the form, it is possible to speak of Russian proletariat as workers while keeping in mind the distinctions between the capitalist market economy and the Soviet one. If, from the economic-structural point of view, the Soviet and the western proletariat differ, from the political viewpoint their interests converge. Both these classes are fundamental to the two systems, and are exploited by them. Both can only liberate themselves through a socialist revolution.’ (p. 20)

Similarly Bahro – rather more definitely – stresses the inapplicability of the term ‘working class’ to describe the direct producers in Russian industry. Since in his account the term ‘bourgeoisie’ is no longer appropriate, the logic of the analysis is that its correlate, the ‘working class’, should not be employed either:

‘Individuals only form a class in so far as they stand in a common antithesis to another class with respect to their positions vis-à-vis the conditions of production and existence. Classes are fundamentally correlative categories, and fit together with all the other elements of the social formation, in particular, of course, with the dominant elements. They can only be defined in terms of the overall disposition of a society. The proletariat loses its specific socio-economic identity together with the bourgeoisie, so that in the post-revolutionary situation it is necessarily completely different criteria, in fact criteria of internal structuring, that become relevant.’ (pp. 184–5)

Bahro also suggests that this difference is registered in the different character of class movements and class organisations among the exploited:

‘The essence of our internal situation is precisely expressed in the way that the working class has no other cadres and no other organizations than that by which it is dominated. In so far as the workers confront the state as the general capitalist, i.e. in the very respect in which they still maintain their old identity as wage-workers, they stand in this confrontation without an other leaders than a few spokesmen who arise spontaneously and are quite untested. The unions, the original fighting organisations for their particular class interests, appear almost exclusively in a supporting function for the state machine ... Deprived of these associations which are adapted to their immediate interests, the workers are automatically atomized vis-à-vis the regime. They are in any case no longer a “class for itself”, and not at all so in a political sense.’

The first and most important that that needs to be remarked about the writers in this school is that, at their best, they produce some extremely valuable descriptive documentation on contemporary social relations in the Eastern bloc. Their insistence on the class character of these social relations, it seems to me, is completely correct, as is their insistence that, in Carlo’s words, the means of production ‘belong to the bureaucracy considered collectively as a class’.

The key difficulty faced by these theorists arises from their argument that what is involved is a new ‘mode of production’, a ‘non-capitalist road to industrial society’. For their accounts of the relations of production in these societies are unsatisfactory. Their descriptions are a great deal more interesting than their explanations.

For Bahro and for Stojanovic, the starting point of their analysis is the alienation of the direct producer from the means of production. It is from the standpoint of alienation, which they (correctly) see as endemic in ‘statist society’ (Stojanovic) or ‘actually existing socialism’ (Bahro), that they criticise these societies.

The problem with this choice of a standpoint for criticism not that it is wrong. Indeed, it is indispensable if a thoroughgoing critique of class society is to ho developed. Without that standpoint, Marx’s critique is reduced to a very paltry criticism of ‘private property’ understood in the narrowest and most legalistic framework The concept of alienation only makes sense precisely because it assumes the possibility of a quite different form of society, in which the ‘associated producers’ do actually control (or even begin to control) the whole process of their own social reproduction. That is, the concept of alienation presumes the possibility of a genuine socialism, and an outline notion of that genuine socialism provides the Marxist critic with a vantage point from which to criticise existing reality. This, essentially, is the procedure of both Stojanovic and Bahro: from that vantage point, the reality of social, political and economic life in Russia and similar countries is found totally wanting. As Bahro writes:

‘our system promises them (the workers) no real progress towards freedom, but simply a different dependence to that on capital.’ (p. 38)

Rather than criticise the standpoint of alienation per se, I want to suggest that it is insufficient. To describe a society as having a system of class relations, of exploitation, is certainly to make important points about the structure of that society. But it does not adequately define it. What is further needed is the development of a ‘political economy’ of that society – or, if you prefer, an adequate sociology. Now, it is precisely the point of ‘political economy’ (and of the critique of political economy developed by Marx) that it permits a differentiation to be made between different historical forms of society. Thus, for example, while both feudalism and capitalism are cases of class exploitation, each must be differentiated from the other if our understanding of them is to be developed. The point of political economy is that it enables us to determine the particular pattern of social relations characterising a particular form of society (or ‘mode of production’), to consider its Taws’ of development, to establish its inner workings, and to examine what may be its potential limits of further development. At this second level of analysis there is a significant difference between the extortion (by force, ultimately) of labour-services and taxes by an Egyptian Pharoah and the exploitation of wage-labour by Imperial Chemical Industries Ltd. Both are characterised by alienation and exploitation, but in different social forms.

It is characteristic of theorists of ‘state collectivism” etc., that they develop little or nothing by way of a ‘political economy’ of these societies. Thus Bahro, for instance, place his key emphasis on a comparison between Marx’s ideal of socialism-communism, and the current reality of ‘actually existing socialism’, How exactly does a society following ‘the ‘non-capitalist road to industrial society’ actually function? What constraints exist, within that society, to limit development in particular directions? What drives such a national economy forward at such a rapid pace, and is this forward drive capable of infinite continuation? If, as Marx argued, the capitalist mode of production is characterised by a tendency for the rate of profit to fall, which tendency provokes crises in the functioning of the mechanism of social reproduction, is any equivalent contradictory mechanism to be found at work in the ‘non-capitalist road’? To such questions, unfortunately, Bahro’s work provides no real answers, and to that extent his critique lacks power.

Stojanovic suggests that that the bureaucratic state in ‘statist society’ disposes of surplus production in its own interests. But what are these interests which he assures us the ruling class pursues? He does not specify them.

Carlo notes, indeed emphasises, that the bureaucracy imposes a definite pattern on the development of production in Russia, and in other ‘bureaucratic collectivist’ societies. The consumption of the mass of the population is continually subordinated to the development and further expansion of Department I industries, producing means of production. Carlo is, in terms of description, absolutely correct. But why is this pattern followed? To this question, Carlo provides no hint an answer.

Ticktin does claim to provide a ‘political economy’ of Russia, but in reality does not do more than describe a series of elements. His conclusion is that ‘the central economic feature of the USSR today is its enormous wastefulness’. In pointing to the high level of ‘waste’ in Russian production and distribution, Ticktin is undoubtedly correct: the Russian press is full of examples. But can one treat ‘waste’ as the ‘central economic feature’? That would be to define the economy as ‘waste-producing’. This is manifestly absurd: after all, people do not starve in millions in Russia (even if they did in 1921–2 and in 1933 – in both cases, for very different reasons than ‘waste’). Economic growth does continue. Capitalism, too, is after all very wasteful, but we would hardly be satisfied with an account of capitalism as ‘waste-production’ pure and simple. [I]

Bahro does at one point ask, what are the ’driving forces’ of his ‘non-capitalist industrial society’. He identifies two elements in the situation: the working class and the bureaucracy. In respect of both, the aspect of their behaviour that he emphasises is that which tends to hold back development: the workers are less productive than their counterparts in the west, and remain so as a result of their alienation in production; the bureaucrats act as tools of ‘simple’ rather than ‘expanded’ reproduction. Thus the elements Bahro stresses are those productive of stagnation rather than expansion. But then, how does economic growth happen at all? Given the historically quite high rates of growth achieved by states on Bahro’s ‘non-capitalist road to industrial society’, how on earth did they manage these? How did impulses which drove them forward originate? However much of a mess the bureaucratic mechanism may have made of planned production, however much ‘waste’ was involved, there was – and to a degree still is – a genuine process of economic expansion, imposed on society from the top. Bahro’s treatment of the ‘driving forces’ is, in reality, quite one-sided: it resembles an account of a motor car which notes the brakes, the rust, the squeaks, but altogether omits to mention the engine. The same, too is true of Ticktin.

The problem arises, in part, from a methodological assumption which these authors make, and which requires to be questioned very seriously. In order to sustain the idea of a ‘non-capitalist path ... parallel to capitalism’, but co-existing with capitalism, they must limit the notion of ‘society’ to strictly national boundaries. In this these theorists treat Russia and the East European countries in the same manner as does Bettelheim, in the crucial sense that they limit their analysis of these countries to their ‘internal dynamics’. They attempt to explain them in isolation from their environment in the world system, or to treat that environment as a strictly secondary element in the analysis. They treat the geographical boundaries of each country as the effective limit of the ‘social system’ in each country. The theory of ‘sate collectivism’ (or whatever title is is preferred) demands the treatment of industrialisation as a process occurring in nation-states as more or less autonomous ‘societies’. Fantham and Machover, for example, look forward to the ending of the ‘bifurcation’ of modes of production – into capitalism and parallel state collectivism – through the development of ‘one universal society’:

‘Eventually we envisage socialism on a world scale which will end the historical bifurcation we have alluded to above. Under socialism the three parts of the world (developed world, collectivist world, undeveloped world) will converge into one universal society.’ (p. 13)

What this theory cannot but play down is the degree to which ‘one universal world’ has already been created, out of processes already begun as far back as the sixteenth century. That this ‘one universal world’ is riven with conflicts and contradictions is beside the point; its ‘one-ness’ as a simple system of interacting parts, or roles, institutions etc is apparent to the most casual observer. Strictly speaking, there is no such thing, any longer, as ‘Russian society’ or British society, etc. The ‘three parts of the world’ to which Fantham and Machover refer are indeed parts of one world, not three separate worlds. It is precisely the achievement of civilization in the past few centuries to have joined up the various parts of the world into a single world society in which the various nations, states, corporations, classes and the like are ‘parts.’ National frontiers can no longer contain the immense productive forces released by the industrialisation processes of the past two centuries. From its beginning, modern production presupposes the creation of a world economy. And this world economy needs to be grasped as a whole, and not merely (as do Fantham and Machover, and others) as a sum of its parts. The importance of this perspective can hardly be over-emphasised – even I is played down or ignored by these theorists. ‘Society’ today cannot be treated as a nationally bounded unit, except for very specifically defined analytical purposes – and certainly not from the standpoint of the definition and delimitation of a ‘mode of production’. We live in a world society, defined in part by its lack of a single political centre, and by the rule of competition between its constituent parts.

Certainly no merely national part of that world society can be adequately considered in isolation from the whole of which it constitutes but one element. [J]

If, however, we bring world economy into the centre of our analysis, a number of the problems faced by the theorists of ‘state collectivism’ can in principle be solved – as they themselves cannot solve them.

Carlo, for instance, is able to describe, but not explain, why how in Russia the production of means of production is given permanent (and growing) precedence over the production of means of consumption. Within Russia considered in isolation from the rest of the world, the activity of Russia’s rulers appears absurd and arbitrary. Were they to expand the production resources devoted to feeding, clothing, housing their people, and generally improving the quality and quantity of the consumer goods, many of the endemic problems of their economy would go away. These authors have, correctly, pointed to the low morale of the workforce, the lack of material reward for higher productivity, the permanent barrier to expansion of productivity, as a feature of these societies. Why do the rulers not meet the demands of their people for consumer goods? To preserve themselves in power? But the people would keep them in power much more readily if they satisfied the people’s everyday wants ... If we consider Russia in splendid isolation from the rest of the world, its rulers appear to be merely irrational. If, on the other hand, we treat the interaction between NATO and the Warsaw Pact as a significant element in the determinants of the behaviour of Russia’s rulers, their behaviour begins to acquire a certain logic: catching up with (or, these days, keeping up with) the West is a critical policy determinant. If we make this move, however the behaviour of Russia’s rulers is partly explained by ‘exogenous’ factors, namely their relation to the rest of world society. And a key underpinning of the theory of ‘state collectivism’ disappears.

Rakovski argues against the ‘convergence thesis’, according to which Russia etc are becoming more and more like the United States etc. ‘Soviet-type societies’, he insists, cannot be understood as variants of capitalist societies. Against (unspecified) western Marxists, who have pointed to similarities in the social structures of the two regions, Rakovski emphasises the differences between the societies of East and West on a number of dimensions. To summarise his conclusions briefly:

Hence, although at a very general level, ‘convergence’ appears a plausible thesis, closer examination throws it into doubt. [K]

There is no question but that these differences do exist between, say, Russia and the United States. One could also point out that within each ‘system’, too, there are significant differences between different countries – between, say, the United States and Japan in terms of security of employment; or between Russia end Hungary in terms of the use of ‘market’ principles a in the domestic economy. The question remains, however, whether it is useful to talk about these various national economies in one frame of reference, or whether ‘bifurcation’ is a more adequate thesis.

In the form in which it posed, Rakovski’s argument is correct. The ‘convergence thesis’, in the form in which it has normally been presented, does not stand up to examination. However, it to exactly the way in which the theory of convergence has been posed that does demand critical attention. The assumption of the convergence theorists – and of its critics like Rakovski or Goldthorpe – has been that each ‘society’ should be considered in terms of its ‘internal’ development, in isolation from world society, as if it were developing in total autonomy. What ‘convergence theory’ has tended to suggest is that the form taken by western technology tends to draw all national societies into a common path of social development: as such, it is a variant of the ‘technological determinist’ approach. It is exemplified in some modern western writing. [83] What the theory does not ask is why there should be such a compulsion to develop technology in the way it is developed. And this question cannot be answered at the national level alone, country by country.

The single area of world production which, in the modern era, uses the largest proportion of scientific and technological know-how, in which the most rapid development of technique is registered, and which is the largest single employer of scientific personnel is ... ‘defence’. Technical development in the ‘defence’ industries syphons off an amazingly high proportion of scientific and technical developmental effort in the advanced countries. And this permanent shaping of overall scientific and technical development by the war-industries is itself incomprehensible without reference to the international relations between states and blocs of states which have defined the parameters of the world since the end of World War Two. The very pattern of ‘challenge-response’ which permeates the arms race between the great powers (and which is replicated in powers of the second and third rank as well [L]) forces onto all the participants in the modem world system a common set of imperatives. If these imperatives are immediately military, they nonetheless reach back into the separate national economies as a crucial set of determinants of production, of production relations, of state forms, etc.

And, in this sense, a kind of ‘convergence’ is indeed forced onto every nation-state – not by any autonomous technological imperative, but by the inter-relations between the states. Of course, this is not a case of ‘simple convergence’ of the kind hypothesised by writers like Clark Kerr. It is better grasped in the kind of terms in which Trotsky tried to understand development in Tsarist Russia, as s situation of ‘combined and uneven development’. The pressures of the world system are felt directly in each ‘part’ of that system, and are responded to differently too. Each ‘part’ is organised differently to meet the challenges of the rest of the system. To this extent, Rakovski’s emphasis on differences is correct – but is also partial, for it misses the element of ‘unification’ which gives these differences their full meaning.

Again, Rakovski and others discuss the ‘economic reform’ period in Russia and Eastern Europe. Rakovski suggests that the whole ‘reform’ movement ran out of steam, but does not ask why it should have been so unacceptable to the central political apparatuses. One of the effects of a thoroughgoing economic reform of the kind proposed by writers like Ota Sik would have been a reduction in the ability of the political centre to pull economic resources constantly in the direction of heavy industry and especially armaments production. Rakovski does not once mention the crucial role of arms production in the overall functioning of ‘Soviet-type societies’. [M] The maintenance of pride of place for ‘defence’ industries in Russia in particular depends on the maintenance of what Rakovski terms ‘a permanent disequilibrium’ in economic, social and political life, which he associates with the Stalin period only, whereas it has in reality been a continuous feature on the Russian and similar national economies since the end of the 1920s. That permanent disequilibrium tendency is incomprehensible without reference to the ‘external’ relations between these ‘Soviet-type’ states and the rest of the world. But Rakovski never mentions these external relations.

Carlo argues that the law of value ‘can operate only in small mercantile production and in capitalism but not in a planned economy’ (p. 75). As far as it goes, the argument is correct. But ho fails to ask ‘what are the concrete determinants of the ‘plan’ (and, to follow through our argument about world economy, is there a ‘planned economy’?) The argument is reminiscent of that proposed by J.K. Galbraith in The New Industrial State. In the United States, Galbraith suggested, at least in the dominant sector of the large corporations, ‘planning’ by large companies, together with the state, was now predominant. The ‘market’ and competition had been overcome by ‘planning’. Whatever empirical truth there was in his observations regarding the USA itself (and there was not that much, even there), Galbraith quite ignored, the international dimension, leaving out of his discussion such phenomena as multi-national corporations, the import-export balance and the whole interrelation between economic ‘planning’ and the foreign policy of the US government. Like other writers, Galbraith treated ‘planning’ as an alternative to competition, treating the rise of ‘planning’ by the state and by corporations as a sign of the ‘overcoming of the market’. In reality, however, such planning is not the reverse of competition, but is precisely a means for engaging in it. Corporations, and states, plan in order to be more effective competitors. Planning is for competition, not against it.

One writer in this school comes closest to the conception for which we are arguing here, although does not integrate his real insights into a theory. Bahro notes ‘the fact that it is still European and American capitalist industrialisation, now joined also by the Japanese, that sets the rest of the world its problems’ (p.127?, emphasis in original), Have noted (quite correctly) the importance of the role of the state in the industrialization of many backward countries, he remarks that the ‘cause’ of this state role is

‘in the last analysis not of an internal nature but of an external one ... (M)odern capitalism and imperialism has borne the germs of dissolution into the stagnant hearths of earlier civilizations, destroyed their social balance and provoked their reorganization. (p. 129)

The first among the ‘historical roots for the subjection of Soviet society to a bureaucratic state machine’ that Bahro identifies, quite correctly, is ‘The pressure of the technological superiority of the imperialist countries, enforced by their policy of military intervention and encirclement.’ (p. 131)

Further, he asks, why should it be that the Stalinist superstructure so obstinately persists, when the industrialisation process has been basically achieved, when the material preconditions of socialism have actually been realised within Russia? He answers his own question:

‘Above all, (because) the measure of accumulation needed for socialism is not determined within the system itself, but rather in so-called economic competition with capitalism.’

And he continues this insight with a brilliant image:

The dilemma of Soviet economic policy is reminiscent of the children’s tale of the hare and the tortoise, where the tortoise bends the rules of the game. Each time the Soviet economy pauses for breath after a bout of exertion, it hears a voice from the end of the course shout ‘I am already here!’ The tremendous burden of military expenditure, which is kept on a par with that of NATO only at the cost of a far greater share of national income, might well be the decisive handicap. The arms race is the real issue at stake in ‘economic competition’. (p. 134)

Bahro appears to supply all the needed materials for a conception of the dynamics of of Russian development, and of the relations of production in Russia, which goes beyond his own idea of the ‘non-capitalist read to industrial society’. Alone among this school he recognizes the significance of ‘external’ relations for understanding Russia:

One part of the present problem is that a form of regulation that figured in the west only as transient and somewhat abnormal could play a decisive role given the unformed character of the developing Soviet economy, which moreover was forced throughout its life to be a kind of permanent war economy. The military-industrial complex in the USA finds its involuntary pendant in the military-bureaucratic complex in the Soviet Union, which together with its security organs proves to be a tremendous brake on internal political progress. (p. 135)

We shall return to this general issue when we look at the last of the theories under discussion in this paper.

The key weakness in the ‘state collectivism’ theory is that already identified. It is also the source of other weaknesses, with which we can deal more rapidly.

As we’ve seen, several of these authors insist on the rejection of a ‘unilinear’ scheme of historical development of the kind defended by Russian propagandists. It is not that they are formally wrong about this, but that their solution to the question is inadequate. The thesis deriving from Trotsky and Lenin, and before them from Marx, of ‘combined and uneven development’, enables us to handle the problem with which these writers try to grapple, without falling into their trap of treating national boundaries as system boundaries. The very idea of combined and uneven development leads us to expect that the form of industrialization in different countries will indeed be different, while also enabling us to discuss the differences in one single frame of reference, that of the development of a unitary world economy.

Secondly, these theorists tend to elide historical events and developments in a very unsatisfactory way. Bahro, for instance, writes of the 1917 revolution in Russia in the following manner:

‘The October revolution ... was and is above all the first anti-capitalist revolution in what was still a predominantly pre-capitalist country, even though it had begun a capitalist development of its own, with a socio-economic structure half feudal, half “Asiatic”. Its task was not yet that of socialism, no matter how resolutely the Bolsheviks believed in this, but rather the rapid industrial development of Russia on a non-capitalist road.’ (p. 50)

This is, firstly, to ignore the internationalist assumptions of the Bolsheviks in 1917, which they did not formally abandon (the party leadership, anyway) until 1924; and, secondly, it is to read as the ‘task’ of the 1917 revolution what only became the actual practice of the Russian state at the end of the 1920s, twelve years later. Those twelve years, from 1917 to 1929, were ‘a long time in Russian politics’. Bahro provides no material for evaluating those twelve years, or for determining the significant turning points in that period. Indeed, most of these writers are notably thin in their treatments of history.

Thirdly, because of the national focus of their discussion, these writers are forced to treat such phenomena as Stalinist industrialization and the forced collectivisation of agriculture as ‘progressive’, in that they were necessary preconditions for the opening of the way to the socialism that the theorists of ‘state collectivism’ etc. espouse. This argument can only be sustained, indeed, if development is conceptualized as a process occurring in autonomous national ‘societies’. The logic of their position (though none of them explicitly discusses the question is that the idea of ‘socialism in one country’ was correct, and in this sense the theories discussed here are semi-apologetic in their attitude to Stalin. Thus, for instance, Bahro:

‘In the countries of actually existing socialism ... the state machine played a predominantly creative role for a whole and decisive period. The Stalin apparatus did perform a task of “economic organization”, and also one of “cultural education”, both of these on the greatest of scales.’ (p. 39, Bahro’s emphasis).

(On the other hand, Stojanovic, who is only concerned with the present situation, and not with generalising a theory of ‘statist society’ beyond the level empirical description, does not adopt this stance: he insists that Stalinism did not represent the highest degree of progress possible in Russia.)

Bahro, in fact, argues in a totally contradictory manner about the ‘progressive’ character of the countries taking the ‘non-capitalist road’. On the one hand he argues the necessity of a despotic state power:

‘What they initially require most of all for their material reconstruction is a strong state, often one that is in many respects despotic, in order really to overcome the inherited inertia. And such a state power can only draw its legitimation and authority from a revolution, and thus put a stop to the decay and corruption characteristic of the old “Asiatic mode of production”.’ (pp. 58–9)

On the very next page he asserts the ‘unconditional need to rebel for themselves’ which the peoples of backward countries have ‘if they are to reshape their society’. In terms of his own analysis and argument, the two propositions are incompatible: a strong state implies the inability of people to ‘rebel for themselves’ and a powerful block to the power of a people to ‘reshape their society’ themselves. Similarly, his advocacy of the ‘progressive’ character of a strong state hardly squares the further development of his argument, assuming that he means what he says:

‘If a socialist or communist order, as we have had since to realise, cannot be based on material preconditions that are merely provincial in character, then the task of overcoming the lack of civilization which Lenin referred to must be fulfilled by the revolutionary peoples themselves, by creating the labour discipline they need in the course of their struggle, this being the major world-historical task in preparing for socialism.’ (pp. 60–1, my emphasis, CB)

Yet, as against this emphasis on the activity of the revolutionary people themselves, Bahro can write the following about the forcible collectivisation of agriculture:

‘In Soviet Russia the peasants were the strongest class in the population, and up till 1928 the sole class to reap the benefits of the social revolution. They had to be the object of a second revolution.’ (p. 102)

Where, now, is the need of the peoples of backward countries to ‘rebel for themselves’? What was needed, says Bahro, was the mass expropriation, the mass impoverishment, of the majority of society ...

The reality is that, because these developments are discussed in a national context, judgments of their ‘progressive’ or ‘reactionary character tend to be highly arbitrary. Characteristically, the writers in this school cannot agree among themselves as to the applicability of the concept of the new mode of production in different countries: Carlo denies it applies to China, while Fantham and Machover say it does; Bahro sees it in Iran, while Fantham and Machover do not; Carlo sees it in Egypt, Fantham and Machover do not. Nor can they agree about the progressive character of the development: Schactman treats Russia as more reactionary than western capitalism; Bruno Rizzi calls these societies ‘slave societies’ but declares they will progress to communism. Some of them see the future options for these societies as being a choice between capitalism and socialism, others see only the socialist option. Those who argue that the development of capitalism is possible (e.g. Fantham and Machover) suggest that this would require a revolution, but fail to explain how Yugoslavia shifted from a ‘Stalinist’ model to a highly decentralized ‘market’ model without major internal disturbances. Fantham and Machover deny that e.g. Russia is ‘imperialist but offer no arguments for this assertion.

The truth is that, because the theory in an arbitrary construction, the conclusions that flow from it are liable to be arbitrary too. Cliff’s comments on Shachtman and Rizzi apply also to the other writers in this school:

‘Actually, if the Bureaucratic Collectivist economy is geared to the “needs of the bureaucracy” – is not subordinated to capitalist accumulation – there is no need why the rate of exploitation should not decrease in time, and as the productive forces in the world are dynamic – this will lead, willy-nilly, to the “withering away of exploitation”. With the dynamism of highly developed productive forces, an economy based on gratifying the needs of the rulers can be arbitrarily described as leading to the millennium or to 1984. Bruno R’s dream and George Orwell’s nightmare – and anything in between – are possible under such a system. The Bureaucratic Collectivist theory is thus entirely capricious and arbitrary in defining the limitation and direction of exploitation under the regime it presumes to define.’ [84]

Kuron and Modzelewski are by far the most interesting of the East European Marxist critics, if for no other reason than that they attempt to put some empirical flesh on their arguments. They show, by using official Polish statistics, that the Polish working class is massively exploited, in that only about one third of the value of their production returns to them as a (very inadequate) consumption fund, while the remainder passes into the control of the ruling class. They insist that what is at issue is not simply the privileged life-style of the rulers of Poland, but their use of the surplus-product. Every ruling class, they suggest, ‘aims at maintaining, strengthening and expanding its command over production and over society; to that end, it uses the surplus product, and to that end it subordinates the very process of production.’ (p. 16)

The class goal which the ‘central political bureaucracy’ imposes on production is not profit for the individual enterprise, but ‘the surplus product on a national scale’. The transactions between the different enterprises and industries are not real acts of buying and selling, as the bureaucracy is the owner of all industry: hence prices ‘are only a tool that serves to count goods, hence their relationships need not correspond to the relationships between the values of the goods.’ (p. 17) The only element involved in production which the bureaucracy does not own is labour power, which it buys from the workers. It buys as a totally monopolistic buyer, who pays out in wages what it reckons the working class needs as a living standard. The class goal of the bureaucracy in production is the expansion of ‘the surplus product in its physical form and the expansion of production, i.e. production for production sake.’ The share of individual consumption in the 1950s and 1960s, they show, fell, as a proportion of the national product.

Kuron and Modzelewski are also exceptional among the East European writers in their perception and documentation of tendencies to economic crisis in the bureaucratic state system they eloquently describe. And, they emphasise, the bureaucracy’s production goal, production for the sake of production, is at the root of the crisis. They draw from their analysis the conclusion that ‘the economic crisis cannot be overcome within the framework of the present production relations ... A solution is possible only through the overthrow of prevailing production and social relations. Revolution is a necessity for development.’ [N] They go on to emphasise that the working class must be the key force in such a revolution: ‘The revolution that will overthrow the bureaucratic system will be a proletarian revolution.’ (p. 54) They assess, relatively optimistically, the international chances for success of such a revolution, arguing that a revolutionary outbreak in one country in Eastern Europe will have the potential to set the others alight as well. [O]

Kuron and Modzelewski’s analysis and argumentation are, it seems to me, exemplary. I would not wish to quarrel seriously with any of their arguments. Yet, considered purely as a sociological account, their Open Letter contains – from the standpoint of this paper – one significant flaw. They do not provide a motive for the class goal they ascribe to the ‘central political bureaucracy’.

They describe that goal as ‘production for production’s sake’. As Marxists, they presumably chose that phrase deliberately. It is a phrase that occurs in Marx’s Capital, volume I, in the context of a discussion of the classical economists’ vision of capitalism:

‘Accumulate, accumulate’. That is Moses and all the prophets ... Therefore, save, save, i.e. reconvert the greatest possible portion of surplus-value or surplus product into capital! Accumulation for the sake of accumulation, production for the sake of production: this was the formula in which classical economics expressed the historical mission of the bourgeoisie in the period of its domination.’ (Penguin edition, p. 742)

As Marx emphasised, it was through competition that this ethic of ‘saving’, of accumulation, of production for the sake of production, was enforced onto each separate member of the bourgeoisie.

The two Polish authors describe a hectic process of accumulation and of production for production’s sake, the subordination of popular consumption to the expansion of the industries of Department A (production of means of production). They declare that this hectic process is at the root of Poland’s growing economic crisis. But they do not discuss by what mechanism this ‘class goal’ is imposed on Polish production As they themselves emphasise, no such mechanism can exist within Poland, where prices are merely administrative, and there is no competitive market between enterprises, all of which are commonly owned by the state, The only hint of a motive is the following remark:

‘The material power of the bureaucracy, the scope of its authority over production, its international position (very important for a class organised as a group identifying itself with the state) all this depends on the size of the national capital. Consequent1y, the bureaucracy wants to increase capital, to enlarge the producing apparatus, to accumulate.’ (p. 17)

There are two possible readings of Kuron and Modzelewski’s work. Hence my placing of it at this point in the discussion of the various theories of Russian and similar societies. The first is that the writers present a version of the ‘new class’ theory – Antonio Carlo, for one, claims them for this school. If this claim is correct, then strictly they have used language incorrectly: they should not use a term like ‘national capital’, they should not say the bureaucracy wants to ‘increase capital’. For ‘capital’ has a very definite meaning in Marxist discourse and implies a whole set of other associated social relations. As it is the argument of the ‘new class’ theorists that Russia etc are not capitalist, the term ‘capital’ cannot be a central plank of their analysis. If it does belong to this school, then Kuron and Modelewski’s work suffers from the same fault as the rest, that it fails to explain why these states have developed as they have. What we then have is a clock without a spring.

The second possible reading – and, without being partisan, the one that best fits their text – is that they are enunciating an incomplete version of the theory of ‘bureaucratic state capitalism’, and that their remark about the ‘international position’ of the bureaucracy is the key to the missing motive.

Let us, anyway, now finally consider this last theory.

(Next part)

>I. In an as yet unpublished paper, Mike Haynes questions whether the focus on waste as a defining feature of the Russian economy is, anyway, justified. Critics like Ticktin. who make much of the ‘waste’ issue, draw entirely on the official Russian press, which itself focuses on issues of ‘waste’ in production and distribution. On the other hand, the Russian press does not discuss at all critically the overall (‘macro’) functioning of the economy. By contrast, in the west the press discusses the ‘macro’ functioning of the economy ad nauseam, but provides very little information in the internal (‘micro’) functioning of enterprises. ‘Waste’ is not documented in the west. Haynes’s suggestion is that perceived differences between East and West are partly due to the information available.

J. Some of the conceptual issues involved are discussed in Barker and von Braunmühl. [80] The significance of ‘external’ determinants of the actions of nation-states is argued strongly in Theda Skocpol’s critique of the work of Barrington Moore, and in her comparative history of social revolutions. [81]

K. The point is not dissimilar to that argued by the neo-Weberian Goldthorpe. [82]

L. See, if nothing else, Michael Kidron and Ronald Segal, The State of the World Atlas (Pan Books, 1981)

M. Ticktin refers to it as ‘massive’ in one place, to suit a particular argument, but denies its significance in another place where it does not suit him. Fantham and Machover, aware of the threat posed by the issue of arms production to their theory, dismiss the questions hurriedly. Stojanovic, who makes no attempt to developed any kind of ‘political economy’, does not refer to the question. Nor does Carlo – his Sinophilia might be upset if he were to probe this questions too closely, for the Chinese ‘defence’ burden is enormous. For Bahro see below.

N. Both Kuron and Modzelewski, who were imprisoned for the publication of their Open Letter To The Party, are active in KOR, the Committee for Defence of Workers, which was set up in 1976 and has played an important advisory role to Solidarnosc in the 1980–81 period. KOR has been attacked by both the Catholic Church hierarchy and by the regime (and by the Russians). However, according to press reports, Kuron at least declares that he no longer holds to the political position he declared in the early 1960s. His political views are now ‘reformist’. It is not known whether he would also argue for a revision of his analysis of the structure of society. Modzelewski recently resigned (March 1981) as an adviser to Solidarnosc in Gdansk; his current political views are unknown.

O. A revised estimate of the danger from Russia may well underpin Kuron’s reported political shift. He has certainly issued documents aimed at Polish workers in the recent past urging them to be ‘very careful not to go too far’ and to risk provoking a Russian invasion. Whether this is revolutionary Realpolitik, or actually a real shift to a reformist perspective, we cannot possibly judge.

77. Svetozar Stojanovic, Between Ideals and Reality: A Critique of Socialism and its Future, translated by Gerson Sher, Oxford 1973; Rudolf Bahro, The Alternative in Eastern Europe, translated by David Fernbach, New Left Books, 1978; Mark Rakovski, Towards an East European Marxism, Allison and Busby, 1978; A. Zimin, On the Question of the Place in History of the Social Structure of the Soviet Union in R. Medvedev, ed., Samizdat Register I, Merlin, 1977.

78. Hillel Ticktin, Towards a Political Economy of the USSR, Critique, 1, 1973; The contradictions of Soviet Society and Professor Bettelheim, Critique, 6, 1976; Class Structure and the Soviet Elite, Critique, 9, 1978; John Fantham and Moshe Machover, The Century of the Unexpected: A New Analysis of Soviet-Type Societies, London: Big Flame publications, 1979; Antonio Carlo, The Socio-Economic Nature of the USSR, Telos 21, 1974; Umberto Melotti, Marx and the Third World, Macmillan, 1978.

79. Max Shachtman, The Bureaucratic Revolution, New York, 1972; Bruno R (Rizzi), La Bureaucratisation du Monde; James Burnham, The Managerial Revolution.

80. Colin Barker, A note on the theory of capitalist states, Capital and Class, 4, 1978 and The State as Capital, International Socialism, series 2, no. 1, 1978; Claudia von Braunmühl, On the Analysis of the Bourgeois Nation State within the World Market Context. An Attempt to Develop a Methodological and Theoretical Approach in John Holloway and Sol Picciotto, ed., State and Capital: A Marxist Debate, Arnold, 1978.

81. Theda Skocpol, A Critical Review of Barrington Moore’s Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy, Politics and Society 4 : 1, 1973; States and Social Revolutions, Cambridge 1979.

82. John Goldthorpe, op. cit. (see note 45).

83. For example, Clark Kerr et al., Industrialism and Industrial Man.

84. Tony Cliff, The Theory of Bureaucratic Collectivism – a critique, International Socialism, 32, spring 1968, p. 16.

85. Jacek Kuron and Karol Modzelewski, An Open Letter to the Party, translation published by International Socialism, London, 1968.

Colin Barker Archive | ETOL Main Page

Last updated: 11 February 2019