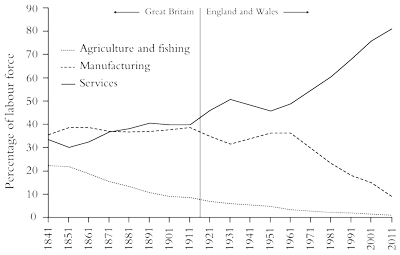

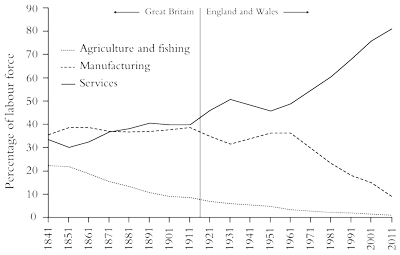

Figure 1: Long term labour market trends in Britain

Source: ONS

Joseph Choonara | ETOL Main Page

From International Socialism 2 : 140, Autumn 2013.

Copyright © International Socialism.

Copied with thanks from the International Socialism Website.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

Neil Davidson has produced a lengthy piece on the neoliberal era in Britain, which raises important questions for us as revolutionary socialists. [1] We agree with much of his narrative. However, the article is a piece of two halves and there are problems with both. The bulk of the article is a detailed exposition of neoliberalism in Britain from 1973 to 2008. On the basis of this, Neil claims that extremely substantial structural changes have taken place in British capitalism and the working class: “the mid-1970s has seen the beginning of a new period in the development of capitalism” in which “both labour and capital were being profoundly restructured”. [2]

The second, and much shorter, part of the article puts forward three propositions. First, that because neoliberalism has involved the devolution of political power to a local or regional level there should be more sensitivity to local issues. Second, that changes in workers’ relationship with reformist organisation requires a novel approach to the formation of left political parties. Third, that the changing structure of the working class, in particular low levels of union organisation in the private sector, along with shifts in workers’ consciousness, means that we must develop a new approach to unionisation.

We share Neil’s view that capitalism involves both continuity and “periodic changes, which are an expression of its historical development”. The economic crisis of the early to mid-1970s signalled the end of the long post-war boom and saw the exhaustion of a set of arrangements by the ruling class that had often been attributed to Keynesian economic policy. Spearheaded by Britain and the US, what followed was a reorganisation of capitalism, which has gone on under what Chris Harman describes as the “rubric of neoliberalism”, [3] to address a succession of crises that were ultimately rooted in the long-term decline in the rate of profit. [4]

Along with the re-emergence of major systemic crises, there was, during the long boom itself and since, a growing global integration of capital, marked by increases in cross-border trade, the formation of regional production networks in some industries and an expansion of international financial flows. [5] It would be bizarre if these changes had not been recognised and analysed within our tradition. For instance, Harman, in Zombie Capitalism, notes these tendencies under the heading “Bursting through borders”:

By 2007 international trade flows were 30 times greater than in 1950, while output was only eight times greater ... The movement of finance across national borders, which had fallen sharply since the crisis of the 1930s, now grew explosively ... If the typical capitalist firm of the 1940s, 1950s or 1960s was one which played a dominant role in one national economy, at the beginning of the 21st century it was one that operated in a score or more countries – not merely selling outside its home country but producing there as well. [6]

However, while recognising these tendencies, we need to distance ourselves from the rigid categorisations of capitalism, exemplified by the regulation school that has characterised the period before and after the crisis of the 1970s as “Fordist” and “post-Fordist” respectively. [7] Equally we need to reject the notion of neoliberalism as a “variety of capitalism” that tries to capture the superficial characteristics of national capitalisms. [8] Both of these approaches focus on the institutions and architecture of capitalism rather than its underlying dynamics.

At no point in his article does Neil offer a definition of neoliberalism or of its intellectual lineage as a strategy of the ruling class – we are left to deduce this from the narrative of the period from 1973 onwards. Though, confusingly, he elsewhere defines it not as a major structural transformation of capitalism but as “those interlocking economic and social policies that have become the collective orthodoxy since the mid-1970s”. [9] The lack of a clear definition of a phenomenon to which Neil accords such transformative power is unfortunate, as it assumes that neoliberalism is a self-evident and coherent set of ideas and that there is agreement on the left as to its content.

For most activists neoliberalism is a short-hand pejorative term for universal and toxic developments in capitalism. However, the first consolidation of the notion of neoliberalism as an ideological project can be traced back to the Mont Pelerin Society in 1947. A group of economists, the leading light among whom was Friedrich von Hayek, drafted a statement advocating a limited role for the state and the centrality of private property and competition. Yet in practice neoliberalism is always and everywhere pragmatic – it is not matter of imposing some blueprint with the clear endpoint of a pure free-market utopia. Taken to its logical extremes, a free market would imply no restrictions on, for example, child labour or the open sale of uranium. [10] More importantly, as Neil acknowledges, neoliberalism has never meant complete liberalisation and/or the retreat of the state – rather it has been about the capturing and restructuring of the state in the interests of capital accumulation and the restoration of profit. It denotes a particular form of state-market relations – not a linear path towards a purely free-market state.

In some quarters the increasing precariousness of employment has been emphasised as part of the neoliberal project. Michael Hardt’s and Antonio Negri’s Empire claims: “Capital can withdraw from negotiation with a given local population by moving its site to another point in the global network”. [11] David Harvey argues that the ability of capital to move enables it to impose increasingly precarious forms of work on workers: “In the neoliberal scheme of things short-term contracts are preferred to maximise flexibility ... Flexible labour markets are established ... The individualised and relatively powerless worker then confronts a labour market in which only short-term contracts are offered on a customised basis”. [12]

The danger with these arguments is that they promote a view that workers are powerless and passive in the face of footloose capital. It has been argued in this journal that accounts of the mobility of capital are both exaggerated and unsubstantiated. [13] As we argue later, claims of a significant shift to insecure contracts in Britain are hyperbolic and do not reflect the reality of changes to work and the working class.

It is important to understand that neoliberalism does not operate as a coherent ruling class strategy – rather it is riddled with inconsistencies, obstacles and contradictions. As Harman points out, we need to differentiate “the claims of any ideology and what those who hold it actually do”. [14] The rhetoric of neoliberalism is one of free markets and competition, yet the reality is the existence of monopolies and oligopolies and the constant intervention by the state to attract and retain capital in its own borders as well as enhancing the competitiveness of its own capitals in the context of global capitalism.

Further, there are divisions and tensions within the ruling class itself regarding the limits of neoliberal policies and their efficacy for capital accumulation, with some sections understanding the high costs of stripping bare the role of the state in reproducing labour and supporting the generation of surplus value. Finally, neoliberalism is not monolithic whereby the strategies of the ruling class are the same in every nation state. Although there are some broad and similar trends it takes different forms according to the configurations of particular states and their historic development. For example, Harvey refers to “neoliberalism with Chinese characteristics” [15] and the variant of neoliberalism in Germany with a much stronger role for the state has been dubbed “ordoliberalism”. [16]

The purpose of making these points is not to engage in an abstract academic argument. However, viewing neoliberalism as coherent, monolithic and universal can lead us to overestimate the self-confidence of the ruling class and the stability of capitalism. Rather an understanding of and emphasis on its limits, weaknesses, contradictions and historical specificity gives us sharper tools for understanding the fragility of capitalism and the dilemmas facing the ruling class.

Two additional problems result from Neil’s approach to neoliberalism. First, because his narrative focuses on Britain, he confuses developments that result from the peculiarities of British capitalism and its place relative to the global system with general tendencies across the system. This includes the declining competitiveness of British capitalism in the two decades prior to 1973. Second, in his keenness to assert the coherence of the changes associated with neoliberalism he confuses much longer-term tendencies within capitalism with features specific to the recent period. Nowhere are these problems more apparent than with his account of the transformation of the working class.

The reshaping of the British working class cannot be understood without emphasising the continuities with the previous period. Over a long period of time there has been a shift from manufacturing to the so-called service sector in all advanced capitalist economies. This has often been somewhat overstated as jobs have been recategorised, and sometimes the content of jobs in these two sectors can be very similar. Despite these qualifications, the tendency is a real one. But it is not a consequence of neoliberalism. It is the result, above all, of the long-term increase in labour productivity due to the accumulation of capital and the raising of what Karl Marx called its “organic composition”. Harnessing an ever greater amount of dead labour (machinery and other equipment) to living labour (workers) raises the productive power of labour. This works alongside periodic attempts to reshape the labour process to make it more productive (through a greater division of labour, the introduction of new techniques or the imposition of greater managerial control, for example).

This means that the same physical output can be generated with fewer workers. Historically this tendency has been most pronounced in manufacturing, both because this is one of the earliest areas of large-scale production under capitalist control and because the nature of manufacturing lends itself particularly well to mechanisation and technical innovation

There are two consequences. The first is that labour is expelled from manufacturing, adding to the reserve army of labour, but ultimately accumulating in other areas of the economy. Second, as productivity rises, the value contained in particular commodities diminishes, making them cheaper. This means that workers can potentially consume a broader range of goods and services on the basis of the same real wage, creating greater scope for the expansion of the service sector in areas such as leisure and retail. In addition, capital itself, as it develops, requires a greater infrastructure of services. For example, the intensification of competition between capitals has spawned new jobs in order to “annihilate space through time”. [17] Competition in terms of time to market, whether in relation to new products or, in the case of supermarkets, from field to shelf, has made logistics and distribution critical. The growing complexity of capitalist production also necessitates a range of accounting, marketing and other functions, which may be carried out within a particular firm or which may be the function of distinct specialist companies.

Furthermore, there has been a massive expansion in jobs in education, healthcare and the wider public sector, in other words those functions that reproduce and maintain labour, or help to provide the infrastructure required by contemporary capitalism in other ways. For example, employment in the health sector had risen to account for, on average, 10 percent of employment across OECD countries by 2009. Education, which produces and trains the appropriate forms of labour power required by contemporary capitalism, has also expanded enormously.

Such developments are not simply associated with the neoliberal period. As early as 1974, Harry Braverman, in his Labour and Monopoly Capitalism, noted:

The service occupations [in the US] ... now include a mass of labour some nine times larger than the million workers they accounted for at the turn of the century. This represents a much more rapid growth than that of employment as a whole, which in the same period (1900-1970), less than tripled ... To this nine million should be added, as workers of the same general classification and wage level, that portion of sales workers employed in retail trade, or some 3 million out of the total of 5.5 million sales workers of all kinds ... These service and retail sales workers, taken together, account for a massive total of more than 12 million workers. [18]

Nor is it true that prior to the neoliberal period workers in Britain were predominantly involved in manufacturing – indeed they never constituted an absolute majority of the workforce. Manufacturing employment, as measured by the admittedly imperfect methods of government statistics agencies, peaked for Britain at around 40 percent in 1911. Already it was smaller than the service sector (see figure 1). Since 1961 it has declined remarkably steadily across England and Wales.

|

Figure 1: Long term labour market trends in Britain

|

Within this general picture there are specificities that have shaped British capitalism. Even if conventional measurements overestimate the shift to the so-called service sector, Britain has faced a long-term decline in the competitiveness of manufacturing. By the mid-1960s the spiral of relative decline was evident with sluggish rates of growth compared with Germany and Japan. Industrial employment fell by 14.8 percent in the UK between 1964 and 1979, while it continued to expand in other economies. The rate of investment in machinery and factories was well below that of Japan and other European competitors. The cumulative impact was reflected in an enormous productivity gap between Britain and its rivals. The world crisis of the mid-1970s exposed the accumulated weaknesses of British capitalism and the state had to bail out the car firm British Leyland, shipbuilding and British Steel. Therefore rather than being in retreat, the first period in Neil’s neoliberal era was characterised by massive intervention by the British state to rescue large failing state firms.

This is the backdrop against which Margaret Thatcher’s reforms and changes to the working class need to be understood. The contraction in manufacturing from 1981 to 1984 was not caused by neoliberalism, but was accelerated and exacerbated by one particular strand – so-called “monetarism” that tightened the money supply and pushed interest rates up to historically high levels. But the rhythms of the British economy are synchronised with those of the world market, and Thatcher’s policies accelerated and amplified a process that would have happened anyway, given the weakness of British industry.

Parallel to the lack of competitiveness in and contraction of the manufacturing sector was the huge expansion of the financial sector. Thatcher abolished international capital controls in 1979 and phased out direct banking controls from 1979 to 1981. But it was the “Big Bang” liberalisation of banking and finance in 1986 that secured Britain’s role as second player, after the US, in recycling the world’s surpluses. Between 1979 and 1988 the capital stock in Britain only rose by 2 percent. But this was highly unbalanced. The net real investment in banking, finance and business services grew at 8.2 percent per year, compared with manufacturing at a mere 1 percent – this laid the foundations for an economy based disproportionally on finance. [19]

Viewed in broad terms, there are today four large groups which make up the bulk of the British working class. The largest single grouping is “public administration, health and education”, including the bulk of public sector workers such as council employees, health workers, civil servants and teachers. By the mid-2000s this was just over a quarter of the workforce. The second is “distribution, hotels and restaurants”, which includes people who work in shops, retail warehouses, catering, hospitality, etc., and which forms about a fifth of the workforce. This is a central component of what we usually think of as the service sector. The third is “banking, finance, insurance, etc.”, formed by about one in six workers. “Manufacturing” is the next biggest group, just below banking. [20] Table 1 shows in greater detail the gains and losses in employment by sector, in both recessions and recovery, from 1979, and underlines a shift in employment from the north east to the south east of Britain.

There was a sharp decline in manufacturing jobs between 1979 and 1983 in the early Thatcher period, particularly in the north east of England. However, jobs continued to be lost in manufacturing even during the recovery of 1993 to 2008. What is particularly marked in the same period is the expansion of employment in the public sector, by 116,600 in the south east and 82,100 in the north east, and the massive expansion of jobs in the finance sector. Note that in this period public sector jobs in the north east accounted for 72 percent of the total expansion in employment (compared with 17 percent in the south east), which makes the north east and similar regions of Britain particularly vulnerable to austerity.

|

Table 1: Structural composition of employment change in recession and recovery, |

||||

|

|

Recession |

Recovery |

Recession |

Recovery |

|

South East |

|

|||

|

Agriculture |

−0.7 |

2.8 |

−12.4 |

−8.3 |

|

Mining, extractive utilities |

−7.5 |

−10.4 |

−5.5 |

−12.1 |

|

Manufacturing |

−116.5 |

−13.7 |

−131.3 |

−119.1 |

|

Construction |

25.4 |

148.9 |

−113.6 |

69 |

|

Retail, distribution, hotels and catering |

25.4 |

200.1 |

−66.6 |

159.6 |

|

Transport and communications |

0.8 |

37.1 |

−23.5 |

42.2 |

|

Finance, insurance and business services |

46.5 |

252.0 |

−5.8 |

364.3 |

|

Other private service |

4.1 |

54 |

−28.9 |

83.9 |

|

Public services |

19.1 |

123.7 |

31.9 |

116.6 |

|

Total |

−27.5 |

794.5 |

−355.7 |

696.3 |

|

North East |

|

|||

|

Agriculture |

−5.6 |

−2.3 |

0 |

−5.7 |

|

Mining, extractive utilities |

−12.2 |

−24.4 |

−13 |

−3.8 |

|

Manufacturing |

−95.4 |

−21.9 |

−35.2 |

−55 |

|

Construction |

21.8 |

21.1 |

−16 |

14.8 |

|

Retail, distribution, hotels and catering |

−34.8 |

16 |

−5 |

14.1 |

|

Transport and communications |

−7.7 |

4 |

−4 |

2.7 |

|

Finance, insurance and business services |

0.9 |

34.6 |

4.9 |

57.1 |

|

Other private service |

2.4 |

7.3 |

1.8 |

8.2 |

|

Public services |

1.1 |

36.1 |

10.1 |

82.1 |

|

Total |

−173.1 |

70.5 |

−56.4 |

114.5 |

In assessing the real changes to the working class Neil slips into some rather dogmatic assertions. He writes:

Because such growth as did take place in the heartlands of the system was based on investment in services rather than manufacturing or other productive sectors of the economy, such new jobs as were created tended to be characterised by more insecure employment or underemployment: “Britain now holds the EU record in the proportion of people employed in such occupations as data entry and call centre reception; there are as many people ‘in service’ (e.g. maids, nannies, gardeners and the like) as there were in Victorian times”. [21]

There are two important claims here. The first is that most new jobs created in the British economy over the recent period are not only outside of manufacturing, but that they are not productive in a capitalist sense. The second is that the new jobs are necessarily more precarious. We will return to the question of precarious working. But is it true that the new areas of employment are necessarily unproductive and, to the extent that this is true, what does it mean for the power of workers?

For Marxists, a job is productive if it creates surplus value for a capitalist through the appropriation of unpaid labour time. Many jobs in the service sector do. At this level, it does not matter whether the worker produces a tangible good or a service. A worker employed by a private bus company is a good example. The profits of the company rest on the extraction of surplus value from workers and if workers withhold their labour, they can hurt capital through preventing it delivering a service and therefore obtaining a profit. So a shift towards services does not necessarily mean that unproductive jobs are being created.

However, as we have argued, capitalism does tend to create an ever greater number of jobs that are not directly productive of surplus value. Nonetheless, under capitalism there are processes that redistribute surplus value both between productive capitalists and between productive and unproductive ones. Generally speaking, those capitalists who run enterprises that are not productive still require workers if they are going to grab some of the surplus value generated elsewhere in the system. In banking, for example, workers are essential if the banking capitalist is to obtain interest payments and other forms of income that ultimately originate in productive work. These workers still have the potential power to prevent banks obtaining their profits by withholding their labour.

There are other areas, notably in fields such as public healthcare and education, where workers do not directly have the power to hit capitalists’ profits. Public sector employment has grown fairly consistently over the past few decades and has retained a level of stability that has allowed union organisation to stay at fairly high levels – over 50 percent. But this is not a privileged layer as many people seem to claim – it is not a “salaried bourgeoisie” as Slavoj Žižek wrote in a piece in early 2012, just after a strike by 2.5 million public sector workers. [22] This is a section of the labour force that has been “proletarianised”, not in the sense of being turned into proletarians (they always were), but in the sense that there is today far less distinction between the pressures, indignities and management techniques applied in schools and hospitals, and those used in manufacturing or large service sector workplaces. These workers increasingly feel part of a common group, facing similar forms of oppression and requiring similar forms of struggle and resistance. [23]

Given that there have been changes to the structure of the working class in recent years, it is important that we are clear on what has and hasn’t changed. Not only do most workers retain considerable collective power, but most are also employed in large workplaces – sites of potential mass organisation. While figures for the UK are hard to come by, in the US, which has seen a similar shift towards service sector employment, [24] the distribution of workplace sizes has been remarkably stable during the neoliberal period (see table 2). [25]

|

Table 2: Distribution of workplace size |

||||

|

|

Percentage of employees |

|||

|

Number of employees |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

2007 |

|

<20 |

26 |

26 |

24 |

25 |

|

20–99 |

28 |

29 |

29 |

30 |

|

100–499 |

24 |

25 |

25 |

25 |

|

500–999 |

8 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

|

1000 and over |

14 |

13 |

13 |

13 |

Given the decrease in the relative numbers employed in manufacturing and the replacement of living labour with dead labour, this suggests the emergence of a large number of big service sector and public sector workplaces to compensate for the relative decline of those in manufacturing. This trend certainly seems to hold for the UK. For example, in 2012 Tesco employed 213,304 (full-time equivalent) workers (the actual number of workers is considerably higher as many are part-time) across 3,146 stores; [26] in 2004 UK airports employed 185,900 workers with 68,427 working at Heathrow alone. [27] These are significant concentrations of workers and offer the objective potential for organisation and struggle.

Nor should we accept that those workers who remain in manufacturing are powerless. The very fact of reduced employment means that the relatively compact groups of workers who remain can have the power to shut down whole networks of production, especially in the most advanced areas of industry, in which production is more likely to be organised across regional networks. By the time of the Ford Dagenham dispute in Britain in 2000-1 there were far fewer workers there than in earlier times. But the engine plant workers could have shut down Ford’s European van production in a day due to the company’s just-in-time production methods. The reason they didn’t had to do with failures of confidence and organisation, and the politics of the union officials, not an objective lack of power.

What of Neil’s second claim regarding the growth of precarious conditions? Generalised claims about insecurity and “atypical contracts” are not helpful; we need to drill down and see what this means. For example, Table 3 gives a breakdown of part-time and temporary workers. The vast majority of those in this category are part-time workers (84 percent), and women comprise 74 percent of all part-time workers. For women part-time work is often a “choice”; only 13.5 percent cited not being able to find full-time employment as their reason for being in part-time jobs. The almost complete absence of affordable childcare for working class women means that, while women want or need to work, full-time employment is simply not an option. By contrast 32.9 percent of men cited not being able to find full-time employment as the main reason for being in part-time employment. But in both cases, part-time work is often permanent and has long-term job tenure.

|

Table 3: Part-time and temporary working (000s) in 2013 |

|||

|

|

Part-time work |

Women in |

Temporary work |

|

All |

7,980 |

5,939 |

1,553 |

|

Managers and senior officials |

573 |

388 |

81 |

|

Professional occupations |

787 |

576 |

293 |

|

Associated professional and technical |

1,023 |

785 |

202 |

|

Administrative and secretarial |

1,143 |

1,025 |

189 |

|

Skilled trades |

324 |

114 |

65 |

|

Personal services |

1,138 |

1,014 |

195 |

|

Sales and customer services |

1,197 |

894 |

113 |

|

Process, plant and machine operators |

212 |

60 |

93 |

|

Elementary occupations |

1,574 |

1,074 |

325 |

The scale of temporary employment is much smaller and between March and May 2013 accounted for 6.6 percent of the total workforce. The fact that 39.4 percent of these workers cited not being able to find a permanent job as the reason for being in temporary works shows that for a large number of workers these contracts were not a choice. However, overall the data on Table 3 does not support the notion of large-scale insecurity.

The increased use of zero hours contracts, in the private and public sector, has been given a high profile recently. These abusive contracts rob workers of security and access to pensions and sick pay; few people would choose to be employed on such conditions. However, they are not a new phenomenon, rather a rebranding of the insecure access to work that has always existed under advanced capitalism for a small layer of workers. Table 4 shows significant fluctuations in the use of these contracts from 2000 to 2012, but with a sharp increase from 2011 to 2012.

The ONS figures in Table 4 show that over the whole period from 2000 to 2012 the increase in the number of people on zero hours contracts is 11 percent, but that in 2012 these contracts accounted for less than 1 percent of employment. Research by the Chartered Institute for Personnel and Development (CIPD) [28] estimates that the figure might be as high as 4 percent of workers – equating to around 1 million people (although their methodology is no more or less sound than that of the ONS).

|

Table 4: Number and proportion of people in employment |

|||

|

Year |

In employment on zero |

Percent in employment |

Percentage change year on |

|

2000 |

225 |

0.81 |

– |

|

2001 |

176 |

0.63 |

−21.7 |

|

2002 |

156 |

0.55 |

−11.4 |

|

2003 |

124 |

0.44 |

−20.5 |

|

2004 |

108 |

0.38 |

−12.9 |

|

2005 |

119 |

0.41 |

+10.2 |

|

2006 |

147 |

0.51 |

+23.5 |

|

2007 |

165 |

0.56 |

+12.2 |

|

2008 |

143 |

0.49 |

−13.3 |

|

2009 |

190 |

0.65 |

+32.8 |

|

2010 |

168 |

0.57 |

−11.6 |

|

2011 |

189 |

0.65 |

+12.5 |

|

2012 |

250 |

0.84 |

+32.2 |

But this remains a small section of the total labour force. Hotels and restaurants, renowned for seasonal work, minimum wages and low union density were the most likely to use zero hours contracts (19 percent of their workers were on such contracts in 2004). The most shocking fact to emerge is the widespread use of these contracts in the public sector (health 13 percent and education 10 percent). The most stark figure is that 61 percent of domiciliary care workers and 30 percent of adult care workers were on zero hours contracts. [29]

Conflating all non-full-time and non-permanent contracts to create a category of “precarious work” can feed into pessimism and hopelessness, diminishing our understanding of how we can fight. For example, the issue of affordable childcare (almost completely absent from current agendas) is central to giving women a genuine choice between part-time and full-time work. Campaigns and action against the use of temporary and zero hours contracts require action by workers on all types of contract, particularly in public sector workplaces with relatively high union densities.

There is indeed plenty of evidence that points in a different direction to that assumed by Neil. Far from the world of work becoming one of increasing instability, the number of people working for the same employer for over ten years has grown over much of the neoliberal period across large swathes of Europe and North America. This is true of the US and Canada between 1983 and 2002 and for the EU states from 1992 to 2002. [30] The predominance of relatively stable employment in the UK is partly the result of the struggle of workers, but it is also rooted in the interests of employers in retaining the skilled labour that they need.

Kevin Doogan points out in his book New Capitalism? that the labour market, rather than being the perfect conductor of changes from the wider capitalist system, is in fact a powerful insulator; it can also absorb and slow down changes. [31] This explains why the crisis and recession of 2008 had a proportionately smaller impact on employment than on output. Rather than lose the so-called “human capital” in which they had invested, bosses tried to cut costs in other ways, by raising the level of exploitation, cutting overtime and holding down wages. This is evident in the deteriorating experience of workers in the workplace that we look at in the next section.

Beyond discussions about the structure of the working class we need to understand what has happened in the workplace in terms of what some people have referred to as the “lived experience” of workers.

The savage shakeout of the 1979–82 recession brought about a doubling of unemployment. This, coupled with successive assaults on trade unions and workplace organisation, put the conditions in place to ratchet up the degree of exploitation, evident in the growth of productivity from 1982 to 1990 (4.9 percent compared to 1.9 percent between 1973 and 79). This intensification of work has continued. According to the Skills and Employment Survey (2012), in 1997 about 23 percent of workers reported working at very high speeds three quarters of the time; by 2001 the proportion had risen to 38 percent; by 2012 it stood at 40 percent. [32] The public sector has experienced the highest reported work intensity. In 1992 about three in ten workers strongly agreed that their jobs required them to work very hard. By 2012 the proportion had risen to over half in the public sector (53 percent) and around two fifths in the private sector. Within the public sector, it was in healthcare that the increase was particularly sharp between 2006 and 2012.

Richard Hyman notes that “human resource management” was always directed at “securing and obscuring” the commodity status of labour power and behind the rhetoric there was always the imperative of extracting more surplus value through cost minimisation, flexibility and downsizing. [33] The past two decades have seen capitalists apply particularly brutal tactics to try to increase their profits. As Phil Taylor documents, this includes performance management, which identifies an arbitrary percentage of underperformers according to targets such as customer satisfaction or behavioural norms, with the aim of “managing” people out of their jobs. Taylor also points to the way in which the management of sick leave over the past two decades has become more draconian with short-term illnesses penalised through the “Bradford factor” [34], the use of return to work interviews and discipline and dismissal triggered by particular levels of absence. The effect of this in the workplace has been to institutionalise bullying as layers of managers are forced to “cascade” pressure to workers below them to meet targets.

There has been much talk of the private sector experiencing a shift from Taylorism (the methods of “scientific management” and the division of labour pioneered by Frederick Taylor in the late 19th century) or Fordism (combining Taylorism with mass production based on assembly lines), towards a more worker-friendly Toyotism (based on techniques supposedly employed by Toyota in Japan), also known as lean production. Supposedly this involves teams of workers participating in shaping the job, who are “upskilled” and “empowered” in order to perform a broader range of roles. This account rests on a number of myths. For one thing, the Fordist model of production was never universal across the private sector. [35] For another, the kinds of technique developed by Toyota were never applicable to a large range of manufacturing or service sector jobs. [36]

Often the introduction of new techniques involved not so much workers developing a richer set of skills or a wider variety of jobs, but an intensification of work, greater managerial control and workers having to undertake a range of semi-skilled or unskilled tasks in addition to their central role – even if, in some cases, this took place under the guise of worker-friendly “team-working”. Fieldwork at “Choc-Co”, which sought to introduce the new techniques from the 1980s, showed that the impact on a traditional food processing workplace based on fairly routine work simply added to the workload and dissatisfaction of many workers. One of the increasingly exasperated “team leaders” told researchers: “They don’t see us as team leaders; they see us as mushrooms: ‘Keep ‘em in the dark and feed ‘em shit’.” [37] Similar results came out of an extensive survey of Japanese firms based in South Wales – the main improvements in productivity came through the intensification of managerial pressure to work harder and faster. Managers’ success in this area was premised on the prior breaking of union organisation in the area. [38]

The various initiatives to intensify work began in the private sector, but they soon spread to the public sector in the form of the “New Public Sector Management” developed in the post-Thatcher period of the 1990s. These methods were ratcheted up by New Labour – first in the civil service and more recently in schools, colleges and universities. While these spheres do not produce surplus value for capital, public sector managers nonetheless have the same interest in intensifying work to increase the amount of work squeezed out of each worker and reduce costs. In other words, these workers face an economic oppression that is equivalent to that faced by workers in the private sector. [39] It should be no surprise that methods new and old, developed in the private sector, have been, and are increasingly being, imported into the public sector. Often, given the difficulty of measuring the output of workers in the public sector in monetary or physical terms, this involves the imposition of seemingly arbitrary “targets” and “metrics”.

The teaching workforce has been remodelled by removing less skilled tasks from teachers and introducing teaching assistants so that the “core” job of teachers is more easily monitored through standardised tests, performance targets and the national curriculum. The fragmentation of the job has created discrete roles making the measurement, standardisation and control of work more transparent, and deepening and broadening managerial control. [40]

Higher education has been subject to a parallel battery of metrics. The performance of departments and individuals is reduced to the production of output published in a narrow and prescribed set of academic journals. Students are “consumers” whose satisfaction is measured by some form of student feedback questionnaire. Even if the response rate is low and unrepresentative, those lecturers deemed to be underperforming will be subject to capability measures and disciplinary action. Massive resources are marshalled towards achieving a high institutional score in the National Student Survey, according to which universities are rated in national league tables. In the institution of one of the authors, lecturers were issued with and instructed to wear “Here to Help Badges” (remarkable similar to those worn in a leading supermarket). Further, the almost complete removal of grant funding and financing of higher education by the exorbitant student fees, as well as an increased reliance on universities generating other income generating activities, means that it is debatable whether universities can be classified as public institutions at all. [41]

The impact on workers is obvious in terms of increasing illness and stress. [42] The most recent Skills and Employment Survey (2012) reports an increase in fear at work. [43] Fear of job loss has increased sharply especially over the period of the recession of 2008–9 with 24 percent of people afraid of losing their job (28 percent in the public sector). In 2012 just under one third of employees (31 percent) were anxious about unfair treatment at work. Just over half of employees (52 percent) reported anxiety about loss of work status. [44] In the public sector there were high levels of anxiety about loss of job status; in relation to “less say” (39 percent), “less skill” (28 percent), “less pay” (43 percent) and “less interesting work” (26 percent). [45] In the past, fear of job loss and fear of unfair treatment were far more common in the private sector than the public sector, but that has now reversed, with public sector workers more anxious.

If the main trend has been the intensification of work, can we explain this in terms of neoliberalism? It is the case that the drive for “flexibility” by reducing the rights of workers and anti trade union legislation reflects neoliberal thinking on competitive labour markets. But the direction of causation is tremendously important. It is not the case that “neoliberalism” has transformed the workplace in such a manner that it becomes impossible for workers to resist the encroachment of capital through traditional means of organisation and struggle. Explanations for the intensification of work are more complex than this. It comes from a combination of bosses ratcheting up exploitation as competition intensifies, the use of technology, in part, providing the means to do so, and the creation of new sites of production with little trade union presence. Importantly, it comes from the defeats suffered by workers in general and specifically their inability to resist new forms of working. But it is not the case that the new forms of work in themselves have eradicated workers’ organisation or the potential to organise.

One consequence of the changes is that people feel far more precarious. As Doogan writes, noting the contrast between the reality of relative job stability and people’s perceptions: “It is therefore important to consider the extent to which job insecurity is suggestive of a shift towards new capitalist employment arrangements or, more prosaically, a deterioration of working conditions, a loss of employment protection and work intensification.” [46] He concludes:

It would be a remarkable own goal if the left championed a cause in such a way as to amplify any feeling of insecurity. A left-wing mindset that sees only temporariness and contingency in new employment patterns is blind to the basic proposition that capital needs labour. Despite all the rhetoric of foreign competition and threats to relocate and outsource, employers generally prioritise the recruitment and retention of labour. Otherwise it would be difficult to explain the international evidence of job stability and rising long-term employment. [47]

Shaking the perceptions of precariousness will take both argument and, crucially, victories by workers that help to give them a sense of their own continued power and capacity to organise.

Neil presents a rather brief argument to the effect that neoliberalism involves the devolution of power to the “lowest elected administrative levels” in order to pass the buck for imposing attacks and cuts to them. [48] This, for Neil, means that the revolutionary party must complement its centralisation with “far greater sensitivity to local situations, not simply in the devolved nations, but at regional and city level, where a variety of different responses and initiatives will be required”, meaning that “general perspectives conceived at a national level ... must be creatively adapted and applied to specific situations which arise at the local level”. [49]

But when was it ever true that revolutionary parties developed a perspective that was applied cookie-cutter style to localities, regardless of the conditions on the ground? As Chris Harman wrote in 1978:

Democratic centralism is essential, not just as an abstract national principle, but as the germ of party activity in each locality or factory ... Does there then have to be blind obedience by the membership to every call from the leadership? There are all sorts of incidents in the class struggle which are not of a vital nature, which a centralised national leadership certainly cannot provide detailed guidance about. Here the unit of decision making is the branch, the workplace organisation of the party, or even the individual militant. The leadership has to try to coordinate these decisions by developing an overall theoretical and political perspective among the membership. [50]

Lenin’s own conception of the party developed in a multinational empire characterised by the fusion of quite different levels of economic development in a complex amalgam. Compared to this, or to the conditions faced by the early Third International that sought to apply Lenin’s methods of organisation to Western Europe and elsewhere, the situation in Britain is one of the relative centralisation and far greater scale of the state, and relatively homogenous conditions for working class people.

Local struggles against hospital closures, academy schools and the bedroom tax, for example, are the outcome of national policies. How these manifest themselves in Lewisham and Liverpool will be different, as will the balance of forces in terms of the numbers of and nature of local activists and tactics used. The role of a revolutionary party is to learn from local victories and defeats, and also to try to generalise these struggles into bigger forces that can defeat specific ruling class initiatives (the poll tax for example), bring down governments and ultimately overthrow capitalism. Of course, we need local and regional sensitivity, but if this involves a substantive departure from our current practice, Neil should say what it is.

Neil is right to point to the weakening of the Labour Party’s roots in the working class. But we shouldn’t telescope this process. Nor should we overstate tendencies. When he says that the membership of the Labour Party is dominated by the middle class, what he actually demonstrates, based on Gerassimos Moschonas’s research, is that its membership increasingly consists of public sector employees, which Neil bizarrely dismisses as the “salaried public-sector middle class”. [51]

Aside from this quibble, there are two problems with Neil’s analysis of reformism. The first is that it can lead us to ignore the emergence of left reformist organisations with roots in the working class – Syriza, Front de Gauche, or even the much more modest revival of the Labour left here, exemplified by the pivotal role currently played by figures such as Unite general secretary Len McCluskey or writer Owen Jones in the movement. In many ways, organisations such as Syriza, as they begin to take root in the working class, are increasingly looking like traditional social democratic organisations, albeit with more left rhetoric than we are accustomed to in recent years. [52]

Second, Neil’s tendency to overstate the decline of traditional reformism leads him to rather ultra-left conclusions. He writes not simply that reforms would now involve a far greater confrontation with capital than in earlier times but that “the possibility of reform” has been “removed” in the recent period. [53] In this context, he says that we have to identify the “form of electoral alternative we think is necessary ... to unify those sections of the class which have broken with or simply been abandoned by Labour”. [54] This sounds rather like the kind of approach to left unity advocated by the likes of the Socialist Party, which believes that simply planting a red flag in the ground will allow it to occupy the whole terrain to the left of Labourism and consequently draw working class people to a “new workers’ party”. As repeated attempts to run candidates across Britain in council and other elections on this basis show, displacing traditional reformist organisation is easier said than done. Simply producing propaganda supporting a particular model does not solve the problem of creating a left alternative to Labour with a real social base.

Neil suggests that there is an overreliance on public sector workers in our strategy. He implies that those who look to the struggles of public sector workers have “a strategy which assumes that the nation will be brought to a standstill by working parents having to stay at home during any future national action by the teachers’ unions”. [55] However, the reality is that a national teachers’ strike does cause massive disruption, to the tune of £2.5 billion per day, according to the government. Other groups of public sector workers have a more direct power to disrupt capitalism – for instance those involved in waste removal, as evidenced by the recent bin workers’ strike in Brighton.

But the importance of public sector workers is not simply their power to cause disruption. The point is that the coordinated public sector strike action that took place in 2011 could, if it had continued and been prolonged beyond one-day strikes, have defeated the government over their attacks on pensions. That was why the containment of their struggle by the union bureaucracy, in conditions where the majority did not have the confidence to fight without the support of their officials, was such a tragedy. [56] One important facet of rebuilding union organisation more broadly is for the better organised groups of workers to win and thus to give others the confidence to fight. We desperately need victories, and a dismissive attitude to the public sector unions does not help us. Neil is therefore wrong to bemoan the fact that in 2011 public sector unions were “decisively important to us”. [57] In 2011 they were of decisive importance to the working class – potentially they remain so.

It is undeniable that union density is significantly lower in the private sector. Even within the public sector high densities of membership are no grounds for complacency. In terms of membership there is much work to do in terms of recruitment, especially in unions with aging memberships, and building branches. In particular, in some workplaces such as in higher education, organising the vast army of workers on fixed-term, hourly paid contracts or zero hours contracts is a priority. In 2012 65 percent of staff in higher education were on full-time contracts and 35 percent on temporary contracts; 63.8 percent of staff were on open ended contracts and 36.2 percent were on fixed term contracts. [58] The fight against casualisation has been an important focus for the UCU Left and indeed the UCU itself. [59]

Further, many public sector workers have a fight on their hands to stop themselves becoming private sector workers. This includes preventing the outsourcing of services to private firms, and campaigns against academies, and for-profit providers on university campuses. Finally, as we have noted, in terms of industrial muscle sustained action by some sections of public sector workers would have a huge social and economic impact on the economy and be capable of provoking a political crisis.

Of course, revolutionaries should attempt to unionise private sector workplaces where the opportunity to do so arises. But here an examination of more recent and real experiences of union activists might be more helpful than a rather vague appeal to the experience in the American automobile or British aerospace industries of the 1930s. [60]

Unfortunately the revolutionary left in Britain is not sufficiently large to substitute for serious recruitment initiatives from the trade unions. That is not to say that there hasn’t been some modest success in this field. Recent migrant workers from the New Member States of central and eastern Europe have been concentrated in the private sector and often in areas without strong trade unions – construction, food processing, logistics and the for-profit care sector, for example. These workers have not always waited to be unionised and have in some cases initiated workplace struggles and organisation on their own account. But since 2004 British trade unions have a reasonably good record of trying, with some success, to recruit and organise migrant workers and “vulnerable” workers in general. However, the resources needed are substantial and sustaining initiatives is often difficult. [61] We need to draw a distinction between actively supporting private sector workers in struggle, building union branches from these struggles, and building solidarity and undertaking routine recruitment with far fewer resources than those of large trade unions. But even more critical than the efforts of the official trade union movement to any real expansion and retention of union members will be struggle – an experience of victories by sections of the class that can build up organisation and present an example for other groups. This element seems to be strangely absent from Neil’s account.

A recent piece co-authored by Neil ended by saying, rightly, that small groups of revolutionaries cannot, in fact, turn round the state of struggle. It concluded by advocating a number of measures including to: “(1) Encourage branches and districts [of the SWP] to work with contacts to produce and distribute workplace bulletins and leaflets. This would improve interventions, force members to find out what was happening in the workplaces, and encourage concrete debate about what to say. (2) Systematically build industrial contact lists in each area and industry. (3) Hold meetings and dayschools to sharpen and develop our rank and file politics and to train activists to organise.” [62] There seems to be amnesia about the interventions the SWP makes on a day to day basis. Even a cursory glance at our weekly bulletin, Party Notes, and the industrial pages of Socialist Worker demonstrates the importance we place on intervening in all struggles of organised and unorganised workers, however small. There is no room for smugness or complacency on our part – we make mistakes and could do better – but intervening and building solidarity is in the DNA of our organisation.

Seeing changes in the structure of the working class as resulting in a decline in collective consciousness and a reduced capacity for organisation and resistance has a long lineage in the post-war period in Britain, both from academics and some on the left. The dynamic nature of capitalism and its continual reorganisation, driven by the law of value, constantly shape and reshape how, where and what goods and services are produced, and in so doing change the structure of the working class. There is no sense at all in which we are denying these changes; rather the opposite is true. In this article we have looked at some of the evidence for precariousness and insecurity and the changing shape of the British working class. Neither do the points argued here exhaust the challenges facing union organisation in Britain. We will need far more debate and discussion of both the problems and opportunities facing us in the period ahead. But, in doing so, we have to avoid the search for magic bullets that can overcome the problems arising, above all, from a long period of low levels of struggle, and we have to avoid echoing the rhetoric of precariousness and impotence, now common to both the left and the right, which can only undermine attempts to raise the confidence and combativity of the working class.

1. Davidson, 2013.

2. Davidson, 2013, pp. 176–177.

3. Harman, 2008, p. 88.

4. Profit rates have not subsequently been restored in a sustained way to the kinds of level they reached during the great post-war boom. Neil seems to think that he is saying something profound when he points out that profit rates had also been falling during the great boom, and not just in the post-1973 period (Davidson, 2013, p. 200). But this is hardly the point-a sustained period of low profitability has completely different consequences for the system compared to one during which they are gradually declining from an exceptionally high level. Neil writes that the “decisive issue is ... whether the rate of profit is sufficiently high for [capitalists] to continue to invest in production and be confident of an acceptable return, and between 1982 and 2007 this was largely the case” (Davidson, 2013, p. 200). Who argues that investment did not take place in this period? But if this is the decisive issue, one might expect Neil to consider the level of investment, and not simply assert that some took place. For more on these issues, see Choonara, 2011, 2012, for a critique of David McNally’s economic writing, on whose work Neil largely seems to rely for his assertions.

5. Davidson, 2013, pp. 178–179.

6. Harman, 2009, pp. 255–257.

7. Aglietta, 1979.

8. There is a huge literature on this. It was initially associated with Hall and Soskice, 2001.

9. Davidson, 2008, p. 36 (our emphasis).

10. See Chang, 2002, for an analysis of the impossible notion of a free market.

11. Hardt and Negri, 2000, p. 297.

12. Harvey, 2005, pp. 169–170, quoted in Harman, 2008, p. 109.

13. Hardy, 2013.

14. Harman, 2007, p. 96.

15. Harvey, 2005.

16. Mirowski and Plehwe, 2009.

17. Marx, 1973, p. 539.

18. Braverman, 1974, pp. 366–367, our emphasis.

19. Healy, 1992. For an earlier account of changes to the British economy, see Hardy, 2005.

20. Additional groups, in declining order of size, are: “construction”, “transport and communication”, “other services” (each around 5 to 8 percent) and, finally, “agriculture and fishing” and “energy and water” (at 1 or 2 percent each). See Begum, 2004, p. 228. Again, the various fairly arbitrary ways of categorising workers mean that these categories are not particularly precisely demarcated. For instance, the category “banking, finance, insurance, etc.” is not quite the same as “finance and business services”.

21. Davidson, 2013, pp. 201–202.

22. Žižek, 2012.

23. Generally across Europe there has been a shift towards mass public sector strikes in recent years. See Choonara, 2013, pp. 64–65.

24. By 2010 about 8 percent of the labour force were classified as being engaged in manufacturing, compared to 79 percent in “service providing” sectors, according to data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

25. Dunn, 2011, p. 67.

26. Tesco Annual Report, 2013.

27. Sewill, 2009.

28. Chartered Institute for Personnel and Development, 2013.

29. House of Commons, 2013.

30. Doogan, 2009, pp. 169–193.

31. Doogan, 2009, pp. 88–113.

32. Felstead et al., 2013, see also Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 1999.

33. Hyman, 1987, cited in Taylor, 2012.

34. This is a formula that gives a numerical value to patterns of absence; the lower the score the better the record-but short-term absences are weighted much more heavily. It is usually used as a disciplinary tool for sickness absence and has led to people being sacked or otherwise discriminated against. See UCU, 2012.

35. See Brenner and Glick, 1991, for a critique of the notion of Fordism.

36. See Bradley, Erickson, Stephenson and Williams, 2000, pp. 31–50, for a demolition of the notions of lean working and Toyotism.

37. Cited in Antunes, 2013, p. 68.

38. Danford, 1998.

39. Carchedi, 1991, p. 30.

40. Carter and Stevenson, 2012.

41. See McGettigan, 2013, for a discussion on the changes in governance and finance in higher education.

42. Green et al., 2013.

43. Gallie et al., 2013.

44. Gallie et al., 2013.

45. Gallie et al., 2013.

46. Doogan, 2009, p. 194.

47. Doogan, 2009, p. 206.

48. Davidson, 2013, p. 210.

49. Davidson, 2013, pp. 210–211.

50. Harman, 1978.

51. Davidson, 2013, p. 212. All Moschonas actually claims is that of Labour’s members “two thirds work, directly or indirectly, in the public sector”. Moschonas considers “the working class in the broad sense” to consist of “workers, foremen and technicians”, who he contrasts to “senior managers, teachers and liberal professions”, who form a “privileged and educated strata”. Whatever else this is, it is not a Marxist account of class. See Moschonas, 2002, p. 121.

52. On Syriza’s role, a powerful example is the way it helped to contain a potential teachers’ strike earlier this year – see Garganas, 2013. See Blackledge, 2013, for a general account of left reformism.

53. Davidson, 2013, p. 195.

54. Davidson, 2013, p. 214.

55. Davidson, 2013, p. 217.

56. Choonara, 2013, pp. 74–75.

57. Davidson, 2013, p. 217.

58. HESA statistics.

59. University and Colleges Union. The UCU Left is a grouping of activists within the union. See Renton et al., 2012, about how UCU Left is campaigning against such contracts.

60. Davidson, 2013, pp. 216–217.

61. Fitzgerald and Hardy, 2010, and Hardy, Eldring and Schulten, 2012.

62. Allinson, et al., 2013.

Aglietta, Michel, 1979, A Theory of Capitalist Regulation: The US Experience (New Left Books).

Allinson, Ian, et al., 2013, Notes on the Working Class, the Balance of Class Forces, the Union Bureaucracy and the Rank and File, available from www.ianallinson.co.uk.

Antunes, Ricardo, 2013, The Meanings of Work: Essay on the Affirmation and Negation of Work (Brill).

Begum, Natasha, 2004, Employment by Industry and Occupation, Labour Market Trends (June 2004).

Blackledge, Paul, 2013, Left Reformism, the State and the Problem of Socialist Politics Today, International Socialism 139 (summer 2013), www.isj.org.uk/?id=903.

Bradley, Harriet, Mark Ericson, Carol Stephenson and Steve Williams, 2000, Myths at Work (Polity).

Braverman, Harry, 1974, Labor and Monopoly Capitalism: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century (Monthly Review).

Brenner, Robert, and Mark Glick, 1991, The Regulation Approach: Theory and History, New Left Review, I/188 (July-August).

Carchedi, Guglielmo, 1991, Frontiers of Political Economy (Verso).

Carter, Bob, and Howard Stevenson, 2012, Teachers, Workforce Remodelling and the Challenge to Labour Process Analysis, Work, Employment and Society, volume 26, number 3.

Chang, Ha-Joon, 2002, Breaking the Mould: an Institutionalist Political Economy Alternative to the Neo-liberal Theory of the Market and the State, Cambridge Journal of Economics, volume 26, number 5.

Choonara, Joseph, 2011, Once More (with Feeling) on Marxist Accounts of the Crisis, International Socialism 132 (autumn 2011), www.isj.org.uk/?id=762.

Choonara, Joseph, 2012, A reply to David McNally, International Socialism 135 (summer 2012), www.isj.org.uk/?id=829.

Choonara, Joseph, 2013, The Class Struggles in Europe, International Socialism 138 (spring 2013), www.isj.org.uk/?id=883.

CIPD (Chartered Institute for Personnel and Development), 2013, Zero Hours Contracts more Widespread than Thought – but Only Minority of Zero Hours Workers Want to Work more Hours, 5 August, www.cipd.co.uk/pm/peoplemanagement/b/weblog/archive/2013/08/05/one-million-workers-on-zero-hours-contracts-finds-cipd-study.asp.

Danford, Andy, 1998, Worker Organisation Inside Japanese Firms in South Wales: A Break from Taylorism?, in Paul Thompson and Chris Warhurst (eds.), Workplaces of the Future (Macmillan).

Davidson, Neil, 2008, Nationalism and Neoliberalism, Variant 32 (summer 2008), www.variant.org.uk/pdfs/issue32/davidson32.pdf.

Davidson, Neil, 2013, The Neoliberal Era in Britain: Historical Developments and Current Perspectives, International Socialism 139 (summer 2013), www.isj.org.uk/?id=908.

Doogan, Kevin, 2009, New Capitalism?: the Transformation of Work (Polity).

Dunn, Bill, 2011, The New Economy and Labour’s Decline: Questioning Their Association, in Melisa Serrano, Edlira Xhafa and Michael Fichter (eds.), Trade Unions and the Global Crisis (ILO).

Felstead, Alan, Duncan Galie, Francis Green and Hande Inanc, 2013, Work Intensification in Britain: First Findings from the Skills and Employment Survey 2012.

Fitzgerald, Ian, and Jane Hardy, 2010, ‘Thinking Outside the Box?’ Trade Union Organising Strategies and Polish Migrant Workers in the UK, British Journal of Industrial Relations, volume 48, number 1.

Gallie, Duncan, Alan Felstead, France Green and Hande Inanc, 2013, Fear at Work in Britain: First Findings from the Skills and Employment Survey 2012.

Garganas, Panos, 2013, Retreat on Greek Teachers’ Strike is an Outrage to Trade Union Democracy, Socialist Worker, 21 May 2013.

Green, Peter, 1987, British Capitalism and the Thatcher Years, International Socialism 35 (summer 1987).

Green, Francis, Alan Felstead, Duncan Galie and Hande Inanc, 2013, Job Related Well-being in Britain: First Findings from the Skills and Employment Survey 2012.

Hall, Peter A., and David Soskice, 2001 (eds.), Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage (Oxford University).

Hardy, Jane, 2005, The Changing Structure of the British Economy, International Socialism 106 (spring 2005), www.isj.org.uk/?id=92.

Hardy, Jane, 2013, New Divisions of Labour in the Global Economy, International Socialism 137 (winter 2013), www.isj.org.uk/?id=868.

Hardy, Jane, Line Eldring and Thorsten Schulten, 2012, Trade Union Responses to Migrant Workers from the ‘New Europe’: A Three Sector Comparison in Norway, Germany and the UK, European Journal of Industrial Relations, volume 18, number 4.

Hardt, Michael and Antonio Negri, 2000, Empire (Harvard University).

Harman, Chris, 1978, For Democratic Centralism, Socialist Review 4 (July–August 1978), www.marxists.org/archive/harman/1978/07/democent.htm.

Harman, Chris, 2007, Theorising Neoliberalism, International Socialism 117 (winter 2008), www.isj.org.uk/?id=399.

Harman, Chris, 2009, Zombie Capitalism: Global Crisis and the Relevance of Marx (Bookmarks).

Harvey, David, 2005, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (Oxford University Press).

Harvie, David, 2006, Value Production and Struggle in the Classroom: Teachers Within, Against and Beyond Capital, Capital and Class 88 (spring 2006).

Healey, Nigel, 1992, The Thatcher Supply Side ‘Miracle’: Myth or Reality, The American Economist, volume 36, number 1.

House of Commons, 2013, Zero Hours Contracts, www.parliament.uk/briefing-papers/SN06553.

Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 1999, Job Insecurity and work intensification, www.jrf.org.uk/sites/files/jrf/F849.pdf.

Martin, Ron, 2011, Regional Economic Resilience, Hysteresis and Recessionary Shocks, Journal of Economic Geography, http://joeg.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2011/09/07/jeg.lbr019.full.

Marx, Karl, 1973, Grundrisse (Penguin).

McGettigan, Andrew, 2013, The Great University Gamble (Pluto Press).

Mirowski, Philip, and Dieter Plehwe, 2009, The Road from Mont Pelerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective (Harvard University).

Moschonas, Gerassios, 2002, In the Name of Social Democracy: The Great Transformation – 1945 to the Present (Verso).

Renton, Dave, Malcolm Povey and Sean Wallis, 2012, Fighting for the Rights of Casualised Workers, Another Education is Possible, number 3 (Winter 2012).

Sewill, Brendon, 2009, Airport Jobs, False Hopes, Cruel Hoax, report for the Aviation Environment Federation, www.aef.org.uk/downloads/Airport_jobs_false_hopes_cruel_hoax_March2009_AEF.pdf.

Taylor, Philip, 2012, Performance Management and the New Workplace Tyranny, Report for the Scottish Trades Union Congress, available from www.stuc.org.uk.

Tesco, 2013, Annual Report, www.tescoplc.com/index.asp?pageid=30.

UCU, 2012, Sickness Absence – the Bradford Factor, factsheet, http://www.ucu.org.uk/media/pdf/a/s/Sickness_Absence_-_The_Bradford_Factor_Factsheet.pdf.

Žižek, Slavoj, 2012, The Revolt of the Salaried Bourgeoisie, London Review of Books, volume 34, number 2./p>

Joseph Choonara Archive | ETOL Main Page

Last updated: 29 April 2022