From the New York Times, Aug. 5, 1951

Vance Archive | Trotskyist Writers Index | ETOL Main Page

Permanent War Economy

From New International, Vol. XVII No. 4, July–August 1951, pp. 232–248.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

It is precisely in its international aspects that the new stage of capitalism, which we have termed the Permanent War Economy, reveals most clearly its true character as well as its inability to solve any of the fundamental problems of mankind. This is not due to any failure on the part of the American state to recognize the decisive importance of foreign economic policy, as witness both the Gray and Rockefeller reports within the past year, but rather to the historical impasse in which capitalism finds itself.

The capitalist world is not what it was in 1919 or in 1929. Even the depression-shrunk capitalist market of 1939 was relatively larger, and offered greater opportunities for profitable investment of American surplus capital, than the crisis-ridden world of today, confronted as it is with the unrelenting pressure exerted by Stalinist imperialism. Just as the domestic economy is increasingly dominated by the impact of war outlays, both direct and indirect, even more so is foreign policy in every ramification subordinated to military (euphoniously termed “security”) considerations.

The tragedy of the situation, from the point of view of American imperialism, as we have previously pointed out (see especially After Korea – What? in the November–December 1950 issue of The New International) and as the more far-sighted representatives of the bourgeoisie perceive, is that American imperialism cannot hope to defeat Stalinist imperialism by other than military means; and yet a military victory, even if it be achieved, threatens to destroy the very foundations upon which capitalism now rests. Not only would the military defeat of Stalinist imperialism remove the entire political base upon which the Permanent War Economy depends for justification of huge war outlays, without which the economy would collapse, but the very process of achieving a military solution of the mortal threat posed by the existence of an aggressive Stalinist imperialism is guaranteed to complete the political isolation of American imperialism undermine its economic foundations and unleash socialist revolution on a world scale.

THE ARENA OF STRUGGLE between American and Stalinist imperialism is truly global, but it necessarily centers on Europe and Asia. There are sound economic reasons for increasing American preoccupation with these areas; aside from their obvious political importance as actual or potential foci of Third Campism. As Defense Mobilizer Charles E. Wilson graphically points out in his second quarterly report (New York Times, July 5, 1951):

Potentially, the United States is the most powerful country in the world but we cannot undertake to resist world communism without our allies. Neither we nor any other free nation can stand alone long without, inviting encirclement and subjugation.

If either of the two critical areas on the border of the communist world – Western Europe or Asia – were to be overrun by communism, the rest of the free world would be immensely weakened, not only in the morale that grows out of the solidarity of free countries but also in the economic and military strength that would be required to resist further aggression. Western Europe, for instance, has the greatest industrial concentration in the world outside of the United States. Its strategic location and military potential are key factors in the free world’s defense against Soviet aggression.

If Western Europe fell, the Soviet Union would gain control of almost 300 million people, including the largest pool of skilled manpower in the world. Its steel production would be increased by 55 million tons a year to 94 million tons, a total almost equal to our own production. Its coal production would jump to 950 million tons, compared to our 550 million. Electric energy in areas of Soviet domination would be increased from 130 to 350 billion kilowatt-hours, or almost up to our 400 billion.

Raw materials from other areas of the free world are the lifeblood of industry in the United States and Western Europe. If the Kremlin overran Asia, it would boost its share of the world’s oil reserves from 6 per cent to over half ... and it would control virtually all of the world’s natural rubber supply and vast quantities of other materials vital to rearmament.

And in manpower, in the long run apt to be the final arbiter, should Stalinism conquer Europe and Asia, American imperialism would be outnumbered by a ratio of at least four to one!

In the words of the Gray Report to the President on Foreign Economic Policies (New York Times, Nov. 13, 1950):

We have now entered a new phase of foreign economic relations. The necessity for rapidly building defensive strength now confronts this nation and other free nations as well. This requires a shift in the use of our economic resources. It imposes new burdens on the gradually reviving economies of other nations. Our foreign economic policies must be adjusted to these new burdens ... Our own rearmament program will require us to import strategic raw materials in greater quantities than before.

Wilson, in his report previously cited, hints at the dependence of the American war economy on the minerals and raw materials of the “underdeveloped” areas:

“For most of these metals [cobalt, columbium, molybdenum, nickel and tungsten and other alloying metals] we are dependent primarily on foreign sources, and defense requirements of other nations are also increasing.”

It remains, however, for the Rockefeller report (Advisory Board on International Development, summarized in The New York Times, March 12, 1951) to place the problem of raw materials in proper perspective, and at the same time to reveal the weaknesses that have accumulated in the structure of American imperialism. The section is worth quoting in full:

With raw material shortages developing rapidly, an immediate step-up in the production of key minerals is vital if we are to be able to meet the growing military demands without harsh civilian curtailments.

Two billion dollars energetically and strategically invested over the next few years could swell the outflow of vital materials from the underdeveloped regions by $1,000,000,000 a year.

This increased production can best be carried out under private auspices and wherever possible local capital within the country should be encouraged to enter into partnership with United States investors in these projects.

Both immediate and longer-range peace needs warn of grave consequences unless such a development program is undertaken promptly. Although the United States accounts for more than half of the world’s heavy industry production, it mines only about a third of the world’s annual output of the fifteen basic minerals.

Soviet shipments to the United States of chrome and manganese, so essential for steel-making, have already been choked back. The advisory board hopes that the people in the Soviet-controlled areas will be able to regain their freedom. However, today their trade is tightly controlled.

In the manganese and tungsten deposits of Latin America, Africa and Asia, the chrome production of Turkey and the Philippines, the timber stands of Brazil and Chile, the pulpwood of Labrador lie resources for developing substitute sources for materials which come from areas now dominated by the Soviets or most vulnerable to aggression.

Continued dependence of the free nations upon imports and markets of Soviet controlled areas weakens them in enforcing measures of economic defense.

Peace, free institutions and human well-being can be assured only within the framework of an expanding world economy.

With an expanding productive base it will become possible to increase individual productivity, raise living levels, increase international trade, meet the needs of the growing populations in the underdeveloped areas and perhaps even resettle peoples from the industrial areas under growing population pressure.

Our objective should not be to “mine and get out” but to strive for a balanced economic development which will lay an enduring base for continued economic progress. Workers should receive a full share in the benefits as quickly as possible.

Improving the standard of living of the people of the underdeveloped areas is a definite strategic objective of the United States foreign policy.

The advisory board recommends the continued encouragement of the free labor unions in the underdeveloped areas.

And that the International Labor Organization’s recommendations as to fair labor standards be used as a guide for minimum labor standards in the underdeveloped areas. (Italics mine – T.N.V.)

Actually, coincident with the outbreak of the Korean war, American imperialism was aware of its vulnerability in strategic materials in the event of continuing “hot” and “cold” war with Stalinist imperialism and sought to remedy the situation. As Paul P. Kennedy puts it in The New York Times of August 5, 1951:

The shift in emphasis from purely economic to economic-military aid within the foreign assistance program began to take vague shape as early as July 1950. At that time Mr. Foster, in something of a surprise move, advocated the diversion, in some countries, of ECA matching funds toward military production facilities.

The Administration has requested $8.5 billion for fiscal 1952, of which $6.3 billion would be in military aid and $2.2 billion for continued economic aid. Economic assistance is now defined as “providing resources necessary for the support of adequate defense efforts and for the maintenance, during defense mobilization, of the country’s general economic stability.” In view of the strong outburst by that staunch defender of democracy and the Democratic Party, Senator Connally of Texas, that “the United States can’t support the whole free world and remain solvent,” it may be wondered why there should be any bourgeois opposition to a program geared exclusively to serving the military-economic needs of American imperialism. The answer lies in two facets of the program that have not been as well publicized as the immediate request for $8.5 billion.

It now appears that the $8.5 billion is intended as only part of a three-year $25 billion program. Mr. Kennedy, in the same article previously cited, states:

“Both Secretary of State Dean Acheson and Secretary of Defense George C. Marshall have estimated that there is little possibility of building up the free world’s fighting force on less than the $8.5 billion the first year, which would be the first installment of $25 billion over a three-year spread.” (Italics mine – T.N.V.)

This is approximately twice as large as forecasts made earlier in the year by Administration spokesmen. Admittedly a large portion of Military Assistance funds will go to Asia and the Pacific area.

Again quoting Mr. Kennedy:

“The ECA answer to Senator Connally’s charge that the United States is, spreading itself too thin by going into Asia and the Pacific area is that; production of materials is the greatest present problem. To get the materials available in Asia, the United States must give in exchange technical and economic assistance, the agency contends.” (Italics mine – T.N.V.)

THE INCREASING DEPENDENCE of American imperialism on foreign sources, chiefly present or former colonial areas, of key raw materials is attributable to many causes. Rapid exhaustion of natural resources, particularly iron ore and petroleum, within the United States, in response to the almost insatiable appetite of the Permanent War Economy for means of destruction and the ability to transport and operate them, is clearly a factor of considerable importance. Along with this has gone the sizable increase in production, coupled with tremendous accumulations of capital, analyzed in previous articles in this series. Historically, however, the decisive factor has been the utter failure of American imperialism to operate in the traditional finance capital manner.

This failure has not been due to any lack of desire on the part of American imperialism to export a sizable portion of its accumulations of private capital, thereby acquiring both markets and sources of primary materials in sufficient quantities to maintain the domestic level of profit and simultaneously to assure a steady flow of those raw materials essential to industry in war or peace. In part, this development has been due to the fateful consequences of the Permanent War Economy. The state, as demonstrated in the May–June 1951 issue of The New International, guarantees profits for all practical purposes. The market incentives to export 10 per cent or more of both production and accumulated capital, traditional in the first three decades of the twentieth century, in order to maintain the profitability of industry as a whole, have atrophied to a surprising extent. The state now consumes the largest portion of accumulated capital. The state likewise undertakes by far the major responsibility for capital exports in the form of government loans and grants. The nature of state capital exports is such, with political considerations predominant, that markets and raw materials tend to be reduced in importance.

In largest part, however, the failure of American imperialism to perform according to the early textbooks is traceable to steady dwindling of the world capitalist market. How can American capitalists invest in Chinese tungsten mines, when China has come within the orbit of Stalinism and American capital has been forcefully driven out of China? Such examples of forcible exclusions of American imperialism from important sources of strategic materials could be multiplied many times since the advance of Stalinist imperialism in the post-World War II period.

Even more significant, however, is the fact that in the non-Stalinist world the climate for American investments has not been exactly favorable. Nationalization, confiscation, the threat of expropriation, and a host of other factors have combined to make private American capitalists extremely cautious about investing surplus capital in any foreign enterprise. This was not the case in the 1920’s, when American net foreign investments increased about 100 per cent during the decade ending in 1931, at which time they reached a peak variously estimated at between $15 billion and $18 billion.

Considering the increases that have occurred in production, accumulation of capital, and the price level, a comparable figure for today would be in the neighborhood of $50 billion! Yet, despite the absence of data, it is clear that American net foreign investments today are lower than they were in 1931. What the precise figure is we cannot say, as recently the first such census since before the war was undertaken by the Department of Commerce and the results will not be available for another year. Nevertheless, according to The New York Times of May 31, 1951, which reported the news of the new census, “Sample data collected by the Department of Commerce in recent years indicate that the new census will show a value of more than $13,000,000,000.” This figure represents direct investments as distinct from portfolio investments, but it is most unlikely that portfolio investments will be more than a few billion dollars, as bonds of foreign governments have not proved very attractive to American investors after the sad experiences of widespread defaults in the 1920’s and 1930’s.

The fact of the matter is that, from the point of view of American imperialism, American net foreign investments should be at least three times their present level. But this is a manifest impossibility, both politically and economically. Neither the capital nor the market is available, even if all the necessary incentives were present, which is obviously not the case.

It may be easier to grasp the magnitude of the problem that confronts American imperialism today if we first look at the figures representing the heyday of American imperialism and then compare them with the present situation. The following tabulation portrays the movement of American foreign investments, both gross and net, from 1924 to 1930.

|

UNITED STATES PRIVATE LONG-TERM FOREIGN INVESTMENTS 1924–1930 |

||

|

Year |

Total of Net New |

New Long-Term |

|

1924 |

$1,005 |

$ 680 |

|

1925 |

1,092 |

550 |

|

1926 |

1,272 |

821 |

|

1927 |

1,465 |

987 |

|

1928 |

1,577 |

1,310 |

|

1929 |

1,017 |

636 |

|

1930 |

1,069 |

364 |

|

Average |

1,214 |

764 |

|

*Includes new foreign loans plus new net direct foreign investment. |

||

The data are based on The United Slates in the World Economy (US Department of Commerce, 1943) and taken from a paper, Foreign Investment and American Employment, delivered by Randall Hinshaw of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System before the 1946 annual meeting of the American Economics Association. During this seven-year period, gross foreign investment was never less than $1 billion in any one year, and averaged over $1.2 billion annually. The large proportion of portfolio investments that existed resulted in heavy amortization payments which, together with net sales by American investors of outstanding foreign securities, reduced the net foreign investment during this period to an average of $764 million. The sizable difference between gross and net foreign investment in 1930 is due to the onset of the world crisis and the large-scale liquidation by Americans of foreign investments which, in turn, aggravated the world crisis.

During the 1930’s, the world-wide depression, plus the acts and threats of Nazi imperialism, caused a shrinkage of American foreign investments of about $4 billion. The Department of Commerce thus estimates total American foreign investments at the end of 1939 at $11,365,000,000. It is apparent that there was a further decline during the war and, beginning in 1946, a relatively modest increase. While the estimates of American foreign investments in the postwar period are undoubtedly quite crude, we summarize below the movement of United States private long-term capital (from the June 1951 issue of Survey of Current Business) as indicative of the pitifully low levels to which traditional American imperialism has sunk:

|

OUTFLOW OF UNITED STATES PRIVATE |

||

|

Year |

Total Outflow |

Net Outflow |

|

1948 |

$1,557 |

$ 748 |

|

1949 |

1,566 |

796 |

|

1950 |

2,184 |

1,168 |

|

Average |

1,769 |

904 |

|

*Includes total of direct foreign investments plus other investments, |

||

While an average net foreign investment of $904 million appears to be significantly higher than the $764 million shown for the period 1924–1930, such a conclusion would be totally misleading. In the first place, the higher figure for 1950 is due entirely to a sharp bulge in the third quarter, amounting to $698 million, which is mostly in the form of portfolio investments, obviously a result of a sharp flight of capital from the dollar following the outbreak of the Korean war. That this was a temporary phenomenon, not possibly to be confused with any resurgence of traditional American imperialism, is shown by the sharp drop in the fourth quarter of 1950 to a mere $60 million of net foreign investment. Moreover, the preliminary figure for the first quarter of 1951 is only $212 million.

In other words, in dollar terms, net foreign investments of American capital are currently at the same level as twenty years ago. While this amount was consistent with the requirements of an expanding American imperialism at that time, today it is nothing but a source of frustration to the policy-makers among the bourgeoisie. For, these exports of private capital are taking place today when gross private domestic investment is averaging about $40 billion annually or more, and when net private capital formation runs from $25–30 billion a year. Net foreign investments at present should actually be at least four times their current level in order merely to match the performance of two decades ago. Another way of expressing the same thought is to equate the present volume of net foreign investments to about $200 million annually to permit direct comparison with the pre-depression period. It is therefore hardly surprising that American imperialism is having difficulties in obtaining adequate supplies of the key raw materials required to keep the economy operating at capacity.

Without doubt, exact information on the changing character and composition of American foreign investments, particularly direct investments, would throw even more light on the raw materials shortage. Unfortunately, it is not even possible to guess at the profound changes that must have taken place during and since the war. We would expect the trend that manifested itself prior to the war, when between 1929 and 1939 American investments in the Western Hemisphere increased from 59 per cent of the total to 70 per cent, to have continued. To be sure, the Western Hemisphere is not exactly barren of raw materials, but aside from a relatively few projects, in such countries as Venezuela and Bolivia, the emphasis has not been on the mining of strategic minerals. Thus, the disparity between the needs of the Permanent War Economy and the ability of American imperialists to deliver the necessary raw materials may be even greater than the dollar figures on foreign investments would indicate.

THE VACUUM CAUSED BY the paucity of private exports of capital has had to be filled by the state. That is the primary significance of the Marshall Plan and all other state foreign aid programs. The amounts have been quite sizable, averaging about $5 billion annually since the end of World War II, even according to the admittedly conservative figures of the Department of Commerce (as reported in the March 1951 Survey of Current Business). The data, by country, are shown in the tabulation below.

|

FOREIGN AID BY COUNTRY |

|||

|

Country |

Net |

Net |

Net |

|

Belgium-Luxembourg |

$ 509 |

$ 174 |

$ 683 |

|

Britain |

1,523 |

4,487 |

6,010 |

|

France |

1,873 |

2,037 |

3,910 |

|

Germany |

3,026 |

67 |

3,093 |

|

Greece |

1,100 |

98 |

1,198 |

|

Italy |

1,689 |

357 |

2,046 |

|

Netherlands |

549 |

381 |

930 |

|

Turkey |

166 |

82 |

248 |

|

Other ERP Countries |

1,837 |

327 |

2,164 |

|

ERP SUB-TOTAL |

12,272 |

8,010 |

20,282 |

|

Other Europe |

1,088 |

451 |

1,539 |

|

American Republics |

135 |

219 |

354 |

|

China-Formosa |

1,567 |

116 |

1,683 |

|

Japan |

1,706 |

14 |

1,720 |

|

Korea |

333 |

21 |

354 |

|

Philippines |

655 |

100 |

755 |

|

All Other Countries |

851 |

265 |

1,116 |

|

GRAND TOTAL |

$18,607 |

$9,196 |

$27,803 |

|

*Assistance that takes the form of an outright gift for which no payment is |

|||

Gross foreign aid by the American government during this period totaled about $30.2 billion, but reverse grants and returns on grants plus principal collected on credits equaled $2.4 billion, bringing the net total to $27.8 billion. How much of the $9.2 billion of credits will be returned and how, much will ultimately assume the: status of outright gifts remains to be seen. It is interesting to note, however, that as of December 31, 1950, according to the Department of Commerce,

“World War I indebtedness [owing to the United States government] amounted to $16,276 million, of which $4,842 million represented interest which was due and unpaid.”

It is also pertinent to observe that preliminary figures for the first quarter of 1951 indicate that net foreign aid exceeded $1.1 billion, amounting at an annual rate to about $4.5 billion for the year. The probability is that the actual figure will exceed $5 billion, as the transition from economic to military aid is well under way.

With two-thirds of net grants and almost 90 per cent of net credits having gone to Marshall Plan countries, the result has been that these major allies being sought by American imperialism have received almost three-fourths of total net foreign aid extended since the end of World War II. Clearly, there is room for expansion of aid in many directions to hoped-for and deserving allies, actual or potential. Nor will, the fact that almost one-half of total net foreign aid has been awarded to Britain, France and Germany escape the attention of those who appreciate the full significance of American military-economic strategy.

The policy of purchasing allies with government grants and credits in order better to contain expanding Stalinist imperialism did not originate with the Marshall Plan, which began operations in April 1948. As a matter of record, more than one-half of total net foreign aid ($14.5 billion out of the $27.8 billion total) was disbursed prior to the launching of the Marshall Plan. The Marshall Plan merely continued an already established policy by changing somewhat the form of aid and creating a new agency to administer it.

Some of the major categories that received forcing aid (on a gross basis) prior to April 1948 are:

|

|

(Millions |

|

Special British loan |

$ 3,760 |

|

UNRRA, post-UNRRA, and interim aid |

3,172 |

|

Civilian supplies |

2,360 |

|

Export-Import Bank loans |

2,087 |

|

Lend-Lease |

1,968 |

|

Surplus property (incl. merchant ships) |

1,234 |

|

TOTAL |

$14,571 |

Thus, these six categories accounted for the overwhelming bulk of foreign aid prior to the ECA program. They reveal quite clearly the unique rôle of “relief and rehabilitation” under the Permanent War Economy. It will be recalled that from 1946–1950 (see Basic Characteristics of the Permanent War Economy in January–February 1951 issue of The New International) indirect war outlays played a crucial role in maintaining the ratio of war outlays to total output at the 10 per cent level. Virtually equal in magnitude to direct war outlays, indirect war outlays were indispensable in maintaining the Permanent War Economy at a successful rate. And expenditures for relief and rehabilitation averaged about one-third of total indirect war outlays during this period. As a matter of fact, there is good evidence to believe that if proper valuation were given to Army-administered supplies, especially in Germany, and Japan, the role of relief and rehabilitation would be even greater than the figures indicate.

Naturally, a large portion of the billions of dollars spent for relief and rehabilitation fulfilled humanitarian purposes. Nor is it possible or necessary to assess the motives that animated Washington at this time. The decisive fact is that relief and rehabilitation expenditures, accomplished what private export of capital could not. The state began to acquire a major interest in foreign economic programs, as well as to relieve any pressure that might develop due to the rapid accumulation of capital. If, in the process, recipients of state foreign aid were “persuaded” to grant American imperialism military bases and to pursue various political and economic policies desired by Washington, so much the better. The quid pro quo generally present in American foreign aid programs became even more obvious with the launching of the Marshall Plan. Objectively, therefore, state foreign aid has served to fill the void left by the failure of private capital to function in a traditional imperialist manner and has served to bolster the political program of American imperialism.

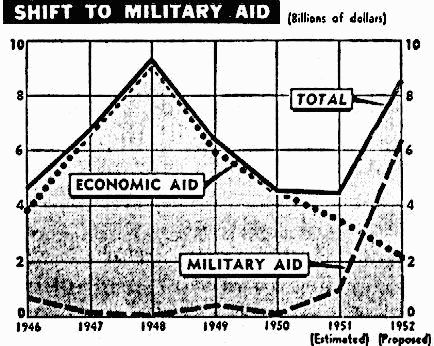

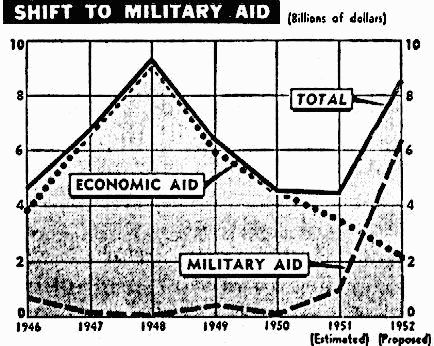

ADMITTED MILITARY AID is now rapidly supplanting economic aid. In reality, of course, the entire foreign aid program directly or indirectly contributes to the grand strategy of American military policy. In this respect, state intervention in the foreign economic field parallels, and even leads, state intervention in the domestic economy, as increasingly a higher proportion of state expenditures are for “defense” purposes. While it is true that the program officially labeled “Mutual Defense Assistance Program,” apparently to be called by Congress “Mutual Security Program,” spent the $516 million included in the total foreign aid analyzed above in the year 1950, it would be a mistake to conclude that admitted military aid occurred only during the past year. For example, there is the so-called Greek-Turkish aid program, which by the end of 1950 had disbursed some $656 million. Of this amount, $165 million was spent prior to the launching of the Marshall Plan, $258 million during the last nine months of 1948, $172 million in 1949, and $61 million in 1950. That this program has been overwhelmingly military in character can hardly be denied. Other programs, such as China, smaller in monetary cost, could be mentioned. As the chart shows, even on the official definition, there has always been some military aid since the end of World War II. Through the first quarter of 1951, military foreign aid has admittedly reached $2 billion. In reality, of course, the figure has been much higher, and now openly exceeds so-called foreign economic aid.

|

|

From the New York Times, Aug. 5, 1951 |

By 1952, admitted military foreign aid is expected to account for three-fourths of total foreign aid. This is without half a billion dollars which overseas bases, included in the military construction program. Officially labeled economic foreign aid, which reached a peak exceeding $8 billion in. 1948, and has been averaging about $5 billion annually, will decline; to an estimated $2 billion. On this basis, even a recalcitrant Congress may be expected to continue to vote for these sizable outlays without too much difficulty. The possibilities of further increasing state foreign aid through pouring dollars into the bottomless pit of “mutual security” are clearly almost without limit. Increasing war outlays have no lack of justifications from the apologists for. and representatives of the bourgeoisie. For sheer brazenness, however, we doubt that the reasons attributed to ECA administrator Foster as justifying the shift from economic to military aid can be equaled.

The arguments forwarded by the administrator at that time [July 1950, as reported by Mr. Kennedy in the aforementioned dispatch to the New York Times] have become more elaborate in proportion to increasing international tension, but basically they are the same arguments now being posed. These are:

(1) Most of the Marshall Plan participating countries are now far enough advanced economically to direct their attention from internal problems to those of possible aggression.

(2) An economy that has been restored must progress in the assurance of protective strength. (Italics mine – T.N.V.)

While comment would be entirely superfluous, under this line of reasoning economic aid would necessarily have to be a prelude to military aid. American imperialism has no choice, nor does it grant any choice to its satellites. The slogan, publicly and privately, becomes: “Join our military camp, or no aid.” While Washington is unduly sensitive to the term, here is a classic expression of imperialist coercion, albeit with new motives and new methods, but with the same tragic results of war, misery and starvation for the masses of humanity.

As we have previously observed, the Permanent War Economy becomes increasingly international in scope, bringing within the orbit of American imperialism every industry and population as yet outside of the orbit of Stalinist imperialism. A detailed analysis of the increase in the ratio of war outlays to total production in England, France and the rest of the non-Stalinist world is unnecessary, nor does space permit. It suffices to point out the rapid rate of increase in the “defense” budgets of the North Atlantic Treaty powers in 1951 as compared with 1950. These increases, according to the New York Times of May 27, 1951, are: Norway, 117 per cent; Denmark, 67 per cent; United Kingdom, 53 per cent; Italy, 53 per cent; France, 45 per cent; and the Benelux countries, 39 per cent. Nor are the bases from which these increasing military expenditures start entirely negligible in terms of the proportion of total output already devoted to means of destruction. The Wilson report, for example, states:

“Our European allies have increased their planned rate of defense expenditures from approximately $4.5 billion a year prior to the Korean conflict to almost $8 billion in 1951. Higher spending rates are projected for subsequent periods.”

It is no wonder, therefore, that Western European capitalism, operating on such an unstable foundation compared with the United States, has already experienced an inflation exceeding the American during the past year. The social consequences in every country, particularly Britain, are profound, but outside the scope of our analysis. Moreover, because of the dominant position of America in the world’s markets, especially in the present scramble for critical raw materials, the economies of every non-Stalinist country, even those with considerable nationalization and far-reaching state controls, are at the mercy of every whim and vagary of Washington, planned, or capricious. Under the circumstances, the low state of American popularity throughout the non-Stalinist world should not be a surprise to the American bourgeoisie.

THE IMPACT OF THIS NEW PHASE OF American imperialism is far broader in its foreign implications than would appear merely from an analysis of the increase in armaments budgets throughout the world, or from the changes in national economies resulting from inflation and steadily increasing state intervention. Precisely because the new method of sustaining American imperialism is geared to the needs of American military strategy, the ultimate consequences may be so far-reaching as to destroy the remaining foundations of capitalism. To combat a Stalinist imperialism operating from the base of bureaucratic collectivism, with its ability to subordinate all its satellite economies to the demands of Moscow and to standardize military equipment, procurement and transportation, requires a more or less comparable “internationalization of war preparations” on the part of American imperialism and its more indispensable allies in Western Europe.

It may still be possible in some circles to question the relative superiority of a nationalized economy over competitive capitalism in ordinary matters of production and distribution, but in the conduct of modern war, and therefore of war preparations, even a bureaucratic, brutal and horribly inefficient Stalinism is incomparably more successful in achieving the necessary coordination and integration of its war-making potential, due to its collectivist base, than the most highly developed capitalist nations could ever hope to achieve without vast structural changes. Under the impact of common financing, centralized administration cutting across national boundaries, standardization of armaments, and pooling of production resources – all of which are indispensable if American imperialism has any hopes of defending Western Europe against Stalinism – national sovereignty must be subordinated to the superior power, economic and military, and wisdom emanating from Washington and its representatives, especially Eisenhower.

A remarkable article on this entire problem, by its chief European economic reporter, Michael L. Hoffman, appeared in the New York Times of Aug. 5, 1951. Its analytical portion is worth reproducing in full:

Nobody can foresee with anything like exactness just how this [a common military budget and a common military procurement administration] would affect the economy of Europe. But European and United States economists have considered the matter fairly carefully already, and the following are some of the consequences that can now be predicted with some degree of confidence.

For practical purposes, national parliaments would lose control of from one-third to nearly half of their own national budgets. They could complain, or refuse to vote taxes, or make all kinds of other trouble, but once in the European army a government would pretty much have to accept its defense burden as given.

It would be quite inconceivable that this degree of rigidity could be introduced into national government budgets without bringing in its train a far greater degree of coordination in budgeting generally than exists now.

Every participating country would acquire suddenly an entirely new kind of interest in its neighbors’ prosperity. It is true now, but not very deeply burned into the consciousness of most people, that Germany cannot thrive without France, France without Italy, and so on. This would become obvious if the taxpayers saw their burdens mounting because some other country could not support a larger share.

Discussions of trade and monetary policy would take place in an entirely new atmosphere, in which everybody would be forced to keep an eye on Europe as a whole.

It could be expected, at the very least, that the duplication and misdirection of investment caused by uncoordinated national armament programs would be reduced greatly. The range of industry affected by military procurement under modern conditions is so great that a unified procurement service for a European army would become the outstanding market for a large number of European industries.

It has been Europe’s experience for ages that the growth of armed forces under the control of governments with sovereignty over larger and larger territorial units generally has been followed by the establishment of currencies, commercial law and other social institutions on a larger and larger territorial basis. There is nothing inevitable about this progression, but those European and United States leaders and officials who have been convinced of the necessity for getting rid of national barriers to economic expansion in Western Europe like to believe that the “law” will work once again. (Italics mine – T.N.V.)

In reality, of course, such integration and coordination as may be achieved in Western Europe can only occur under the stimulus, organization and direction of American imperialism. European capitalism is long since incapable of saving itself. Were it not for the aid and support received from the American bourgeoisie, the European bourgeoisie would have abdicated or been overthrown. Farfetched and alarming as it may seem, the Kautskyian theory of “ultra-imperialism” may yet see its realization, in the event the Third Camp fails to intervene actively in the course of history before it is too late, in the form of world hegemony being achieved by either American or Stalinist imperialism.

The role of military aid in the new phase of American imperialist development will be even more pervasive and all-embracing than the role of relief and rehabilitation. With overriding priority over materials, production facilities and manpower, military aid appears to be the vehicle that will permit American imperialism to complete its task of subjugating the economies of the lesser capitalist imperialist powers, of controlling their basic international policies, of influencing their domestic policies, and, above all, of dominating their colonial markets and trade. Naturally, there will be struggles, intense social conflicts, in many countries where the ability and will to resist subordination of legitimate class and national interests to Washington remains. Stalinism will naturally seek to exploit these contradictions wherever they appear. What the outcome of these complex stresses and strains will be may well determine the course of history for decades. Of one thing, however, we may be absolutely certain: the restoration of traditional American finance capital imperialism to sound health is excluded.

THE NEW POLICY OF AMERICAN imperialism, judging by its most eminent official and private spokesmen, is heartily in favor of the bloodless conquest of Europe and its empires, yet it seeks to accomplish this strategic aim by emphasizing the old, traditional methods, while paying lip-service to the new methods imposed by the exigencies of the times. The objective of European political union, with implied American control, has been voiced by innumerable leaders of the American bourgeoisie. Notable among these has been Mr. R.C. Leffingwell, head of the House of Morgan, who in an article in Foreign Affairs for January 1950, entitled Devaluation and European Recovery, states:

“Monetary union without political union is impossible. There cannot be a common currency without common sovereignty and a common parliament and common taxes and common expenditures.”

Or, in the more oblique language of the Gray report (recommendation 21):

“The United States should help to strengthen appropriate international and regional organizations and to increase the scope of their activities. It should be prepared, in so far as practicable, to support their activities us the best method of achieving the economic and security objectives which it shares with other free nations.”

In the area of investment policy, the key to imperialist activity and perspectives, the language of publicly enunciated foreign economic policy more clearly parallels that of private sources. Leffingwell, for example, in the article cited above, comments on the fundamental contradiction of American imperialism as a creditor nation with a large favorable balance of trade, as follows:

As a creditor nation, our tariffs should be for revenue only, except where needed to protect industries essential for the national defense ... What we need to do is to increase our imports more than we increase our exports ... Private American foreign investment would help. Indeed, the fundamental trade disequilibrium is so great that the international accounts can scarcely be balanced without great American investment overseas, both public and private ... If American foreign investment is to be encouraged, our government and foreign governments must reverse their policies and give firm assurance to American investors that their investments will be respected and protected, and that they may hope to profit by them, and collect their profits.

Almost as forthright is the Gray report:

Private investment should be considered as the most desirable means of providing’ capital and its scope should be widened as far as possible ... Further study should be given to the desirability and possibility of promoting private investment through tax incentives, in areas where economic development will promote mutual interests, but where political uncertainty now handicaps United States private investment.

Two specific steps are advocated for immediate action to stimulate private investment:

“(a) The negotiations of investment treaties to encourage private investment should be expedited; (b) The bill to authorize government guaranties of private investment against the risks of non-convertibility and expropriation should be enacted as a worthwhile experiment.”

Since all this encouragement of private investment may be expected to remain confined to paper, the Gray report also places “heavy reliance” on public lending, and seeks to “make sure that our own house is in order – that we have eliminated unnecessary barriers to imports, and that our policies in such fields as agriculture and shipping are so adjusted that they do not impose undue burdens on world trade.”

Here, again, the public spokesman must be more circumspect than the private. Says the Gray report:

“With respect to our own agricultural policies we should, over the long-run, attempt to modify our price support system, and our methods of surplus disposal and accumulation of stocks, in ways which, while consistent with domestic objectives, will be helpful to our foreign relations.”

Such double talk, together with the limitation proposed for shipping subsidies, is, of course, aimed at achieving the same objective as Leffingwell: abandonment of the American farmer so that industry may resume its customary exports of commodities and private capital.

EVER SINCE 1917, WHEN THE UNITED States became a creditor nation, the basic contradiction inherent in a finance capital imperialist nation exporting private capital while simultaneously maintaining a substantial export surplus in commodities and services has become more acute. The essence of the problem is clearly the necessity to make it possible for recipients of American private capital to pay the carrying charges, to remit the profits, and ultimately to repay the loans and investments. In the 1920s the problem was solved through large-scale remittances abroad of recent immigrants to the United States, coupled with ultimate repudiation of a substantial portion of American-held foreign securities. In the long run, however, if American imperialism is to function in the traditional manner, the United States must import more than it exports; i.e., it must acquire an unfavorable balance of trade sufficient to cover the tribute exacted by American capital. To be sure, remittances of gold temporarily help to achieve the necessary balance, but the United States has long since acquired the overwhelming portion of the world’s gold supply. Foreign countries, fundamentally, can only earn the dollars they need by carrying the majority of trade in their own ships, by inducing American tourists to spend a sizable amount of dollars abroad, and by exporting more commodities to the United States than they import from the United States. Since, with relatively few exceptions, foreign countries cannot compete with American manufacturers, they are reduced to exporting to the United States raw materials, minerals and farm products.

When England was confronted with a similar problem in 1847, she repealed the “Corn Laws,” permitting foreign wheat and other agricultural commodities to be imported into England without tariffs. The result was the abandonment of British agriculture, accompanied by a gigantic increase in industrial output. Perhaps, if the Farm Bloc were not so strong, American imperialism might have been able to achieve a classic solution of its crucial imperialist contradiction. It is, however, politically impossible and historically too late to solve the problem in this manner. The experience of the last few years indicates the only way in which American imperialism ran hope to continue to maintain an export level between five and ten per cent of total output, as the following data (from the June, 1951, Survey of Current Business) show.

|

AMERICAN EXPORTS AND MEANS OF FINANCING, 1948–1950 |

|||

|

Item |

1948 |

1949 |

1950 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

$16,967 |

$15,974 |

$14,425 |

|

Means of Financing |

|

||

|

Foreign sources: |

|||

|

United States imports of goods and services |

10,268 |

9,603 |

12,128 |

|

Liquidation of gold and dollar assets |

780 |

–60 |

–3,645 |

|

Dollar disbursements (net) by: |

|||

|

International Monetary Fund |

203 |

99 |

–20 |

|

International Bank |

176 |

38 |

37 |

|

United States Government: |

|||

|

Grants and other unilateral transfers (net) |

4,157 |

5,321 |

4,120 |

|

Long and short-term loans (net) |

886 |

647 |

164 |

|

United States private sources: |

|||

|

Remittances (net) |

678 |

522 |

481 |

|

Long and short-term capital (net) |

856 |

589 |

1,316 |

|

Errors and omissions |

−1,037 |

−785 |

−156 |

American exports of almost $17 billion in 1948, almost $10 billion in 1949, and more than $14.4 billion in 1950 amounted to 7 per cent, 6.8 per cent, and 5.6 per cent, respectively, of net national product. This is relatively less than the ratio that “normally” prevails with the exception of years of deep depression. Its importance cannot be measured simply by reference to the absolute amounts involved. For many industries and, by and large, for the economy as a whole, the profitability of the remaining 90–95 per cent of output that is sold on the domestic market depends on maintenance of these exports. It is not only that exports make possible indispensable imports, but that surplus value is created at every stage in the process of production. Elimination of all exports, aside from certain obviously serious political and economic consequences, would not merely reduce profits of certain industries, possibly sending them into bankruptcy, but would immediately lower drastically the rate and mass of profit for all industry, and with cumulative effects.

Even though imports have been at the $10 billion level, the visible surplus in the balance of payments for commodities and services was $6.7 billion in 1948, almost $6.4 billion in 1949, and $2.3 billion in 1950. The narrowing of the gap in 1950 is due more to the rise in imports as the scramble for raw materials developed after the outbreak of the Korean war than to the fall in exports. It was more than offset, however, by the flight of gold and dollars from America as “hot” money sought the greater safety of haven in Uruguay and other places.

It is clear that American government funds have been decisive in maintaining exports. Obviously, without state foreign aid, exports would have been some four or five billion dollars less, which in turn would have had a severely depressing effect on both the American and world economies. It is equally evident that if you give the purchaser the means with which to buy what you have to sell, you can continue to do business as long as you are able to maintain your customer’s purchasing power. This is equivalent to a perpetual subsidy in the present case by the American state on the order of $5 billion annually. How long American imperialism can maintain foreign subsidies of this magnitude, now to be increased to a level of $8 billion as foreign aid shifts from predominantly economic to military commodities, is uncertain, but there is a limit and there will be a day of reckoning.

An increase of American foreign investments “from the present $1,000,000,000 a year to a minimum of $2,000,000,000 a year,” as called for by the Rockefeller report would not begin to solve the problem of the dollar gap. Moreover, as American foreign investments accumulated over the years,. assuming that any such recrudescence of traditional American imperialism was possible, the interest and dividend bill would likewise increase, and foreign countries would eventually be even shorter of dollars than at present. Let us not forget that the returns of capital invested abroad historically are much greater than the domestic rate of profit. That is one of the chief attractions of finance capital imperialism. An example of current profitability is provided by the report “that the Prince of the Kuwait Sheikdom has rejected a new offer of the Anglo-American-owned Kuwait Oil Co. to boost his oil royalties ... The offer of the company was to up the royalties from four and a half shillings to 25 shillings (63 cents to $3.50 a ton).” (World Telegram and Sun, Aug. 6, 1951.) In other words, to forestall any desire to emulate the nationalization action of Iran, the Kuwait Oil Co. is able to offer an increase of 450 per cent in the royalty paid. The Prince of Kuwait is said to have rejected this offer and to be holding out for a 50-50 split of profits!

Barring a sharp rise in privately-financed imports, which is virtually impossible, American imperialism is forced to place its main reliance in achieving practically every objective of foreign economic policy on continued state aid. Private foreign trade and investments, as in the case of domestic profits, are in effect guaranteed by the state, and the state itself must make good the failure of private investment through permanent gifts and loans.

IN PROMULGATING THE POINT FOUR program on Sept. 8, 1950, Truman declared:

“Communist propaganda holds that the free nations are incapable of providing a decent standard of living for the millions of people in the underdeveloped areas of the earth. The Point Four program will be one of our principal ways of demonstrating the complete falsity of that charge.”

The mountain has labored and brought forth a mouse. Thirty-four and a half million dollars was appropriated for the first year. The appropriation for the second year will be considerably less than the $500,000,000 recommended by the Gray and Rockefeller reports. Inasmuch as the Gray report was devoted to foreign economic policy as a whole, while the Rockefeller report concentrates on development, it is to the Rockefeller report that we must turn for an authoritative statement of American hopes and policies in this field.

“The people who live in what have been termed the underdeveloped areas of Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, Asia and Oceania need our help and we need theirs,” states the Rockefeller report. Point Four is thus not entirely a one-sided and exclusively humanitarian venture.

“Considered from the point of view of the strategic dependence of the United States on these regions, it must be emphasized that we get from them 73 per cent of the strategic and critical materials we import – tin, tungsten, chrome, manganese, lead, zinc, copper – without which many of our most vital industries could not operate.” (Italics mine – T.N.V.)

The major recommendation is, consequently, an expansion of Point Four:

A balanced program of economic development calls for simultaneous progress in three broad fields of economic endeavor. Along with the production of goods – which is a job for private enterprise – must go public works, such as roads, railways, harbors and irrigation works; also improvement in the basic services, like public health and sanitation, and training people in basic skills. The financing of both the public works and these basic services are largely governmental functions.

The Gray Report on United States foreign economic policy, submitted to the president last year, recommended that United States economic assistance to the underdeveloped areas be increased “up to about 500 million dollars a year for several years, apart from emergency requirements arising from military action.” The advisory board believes that the expenditure of $500,000,000 in these areas is justified. (Italics mine – T.N.V.)

How an expenditure of 50 cents per person annually can have any material effect in raising living standards in the colonial areas is carefully avoided, as there is opposition within the bourgeoisie even to this pathetically small amount. Consider the following from the August 1951 Monthly Letter of the National City Bank:

“The difficulty with development is not lack of money, but such factors as lack of skills to use modern machinery, political instability, prejudice against foreigners, onerous taxation and arbitrary limits on business profits. It is doubtful if the American taxpayer should venture, through the Export-Import Bank, where neither the private capitalist nor the World Bank has dared to tread.”

Earlier, we pointed out that the Rockefeller report, like the Gray report, places its main reliance on stimulating private investment. While “a full kit of financial tools” is recommended, as usual it is the matter of lax incentives that is most revealing:

Adoption of the principle that income from business establishments located abroad be taxed only in the country where the income is earned and should therefore be wholly free of United States tax.

To avoid any drop in tax revenue during the emergency we recommend that only new investment abroad be freed of United States tax during the present emergency. As soon as the emergency is lifted the exemption should be extended to future income from investment abroad regardless of when the investment was made.

This would apply to corporations. Individuals would receive only partial exemption.

It may be anticipated that such tax concessions will not be very popular. Together, however, with the guaranties offered in the Gray report, it is clear that the bourgeoisie is desperately seeking every expedient to restore its former position. The sentiments underlying the humanitarian side of Point Four should not be minimized. They correspond to a vast yearning by the majority of the human race for emancipation from misery, starvation and exploitation. A socialist America could make real strides in helping the underdeveloped areas rapidly to overcome the backwardness imposed by centuries of feudal and imperialist exploitation. But a capitalist America can do little more than produce reports and a pittance of genuine aid.

|

August 1951 |

Permanent War Economy

Vance Archive | Trotskyist Writers Index | ETOL Main Page

Last updated: 16 August 2019