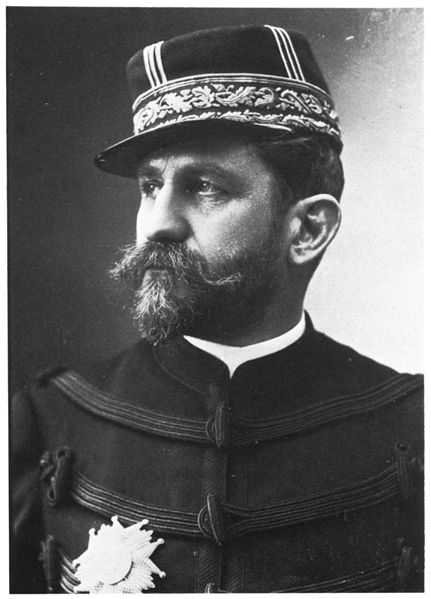

On September 30, 1891 a distraught Frenchman, Georges Boulanger, a former general in the French army and a fugitive from French justice, committed suicide at the gravesite of his late mistress in the cemetery in Ixelles, Belgium. With this act the epic of Boulangism, the movement inspired by Boulanger that had quickly grown and quickly died, which had swept France and had nearly resulted in the death of the Third Republic and the establishment of a dictatorship, had come to an end.

The movement that had grown around Boulanger’s name was perhaps the first of its kind, a combination of royalists, Bonapartists, Republicans, socialists, and Blanquists. If it resembles any movement in this strange mix of followers it is Peronism, which was also able to attract followers from all ends of the political spectrum around the figure of a general. And like Peronism, Boulangism was able to do this because it can justly be said of the man at the heart of it that, like Gertrude Stein’s Oakland, there was no there there.

It was able to do this, people of all political stripes were able to see Boulanger as one of their own, because the program of General Boulanger, published as a broadsheet in 1888 was full of empty phrases: “Boulanger is work,” “Boulanger is honesty,” “Boulanger is the people” ... He called for a revision of the constitution, yet never said in what that revision would consist. His slogan of “dissolution, revision, a constituent assembly” repeated slogans that had been in the air for years. And yet, the vast movement that rallied around him and attracted followers from all classes, all professions, and all political beliefs nearly put an end to the republic.

But more significantly, in the words of the historian Zeev Sternhell in his “La Droite Révolutionnaire” (The Revolutionary Right), “Boulangism... was, in France, the place where and a certain form of non-Marxist, anti-Marxist, or already even a post-Marxist socialism were stitched together.” But for Sternhell Boulangism goes even farther: The synthesis of the various currents that united behind the general included Blanquism, “which rose up against the bourgeois order , [and] the nationalists [who rose up] against the political order that is its expression.” This amalgamation was to result in something far more grave: “After the war this synthesis would bear the name fascism.”

And so we must ask, who was Georges Boulanger and what precisely was Boulangism?

Georges Boulanger himself was a career military man who, in 1870, participated in the defense of Paris against the Prussians and who fought against the Commune. But he was wounded in the fighting and did not participate in the massacres of ten of thousands of workers during the Bloody Week that ended the Commune. This fortuitous wound would allow him to obtain working class support that otherwise would have been denied him.

In January 1886, at the recommendation of his high school classmate (and future political foe) Georges Clemenceau, Boulanger was named Minister of War in the Freycinet government, quickly moving to implement laws and regulations that earned him popular support. Forestalling any possibility of a coup, he transferred a group of royalist officers to posts distant from each other, and members of royal houses were expelled from the army. He also implemented seemingly minor reforms that earned him even greater popularity, authorizing the wearing of beards, modifying uniforms, and replacing straw mattresses with spring mattresses. In a presage of what was to come, and in what was to serve as a stage on his road to power, he re-established the Bastille Day review, and of greater importance still, he refused to send troops to crush a strike in the town of Decazeville.

At the first of the reviews, that of July 14, 1886, Boulanger received more applause than the president, Jules Grévy, and in another foreshadowing of what was to come, his presence at the review inspired the writing of a popular tune: “En r’venant d’la r’vue” (“While Goin’ Home From the Review”) At the height of his popularity the writing of songs about the man and the mass production of his image were hugely profitable industries.

Boulanger firmed up his nationalist credentials by his role in the Schnaebelé Affair, in which a French spy, Gustave Schnaebelé was seized by German authorities on French soil. The spy had been put to work by Boulanger as Minister of War without consulting with his colleagues, which caused disquiet in government circles. But the spy ring had been established with an eye to recapturing the provinces lost in the Franco-Prussian war, which earned Boulanger the admiration of the revanchist right.

Populism, nationalism, defense of the rights of workers; everything was in place for the birth of the movement that would bear the general’s name.

Boulanger’s popularity had become so bothersome to those in power that he was not only removed from his ministry in May 1887, but the Rouvier government decided that the time had come to send him far from the Parisian crowds that so adored him. But when on July 8, 1887 he climbed aboard the train that was to take him to his new posting in Clermont-Ferrand, a crowd assaulted the train and tried to prevent the general’s departure.

And already, without having formally presented himself as a candidate, at the call of the propagandist Henri Rochefort, Boulanger had received 100,000 votes in partial elections in the district of the Seine.

Early in 1888 Boulanger’s political base widened when he met in secret with Prince Bonaparte, as a result of which he was officially presented as the Bonapartist candidate in seven departments. The ironies and contradictions already abound: Boulanger the Bonapartist candidate is loudly supported by Rochefort, whose opposition to Louis Bonaparte had led to his exile.

The contradictions and ironies were to only increase when Boulanger had his military functions lifted because of his electoral activities and he was elected to the Chamber of Deputies in 1888 after running in two departments.

Boulanger, with his growing support, was now viewed by all those who opposed the republic as the man of the hour. Monarchists gave him their support as the person most likely to destroy the bourgeois republic they so hated; the extreme left gave him their support as the man most likely to bring down the bourgeois republic they so hated. The most vocal of nationalists, Paul Déroulède and his League of Patriots, and Maurice Barrès, the literary voice of the right, were active supporters. The Boulanger machine was in full motion.

From 1888-1889 Boulanger went from victory to victory, winning elections in seven different districts. Blanquists, the most intransigent of revolutionaries (but who were not immune to the temptations of nationalism and anti-Semitism) , were to say that with Boulanger “the revolution has begun,” and that Boulangism is “a labor of clearing away, of disorganizing the bourgeois parties.” So close were the ties between the extreme left and Boulangism that the police were convinced that secret accords had been drawn up between the two forces. And though the official Blanquist bodies were split as to how far they’d go in following Boulanger, it is a fact that the Boulangist movement’s strongest electoral showing was in the Blanquist strongholds in Paris. Indeed, throughout France, it was in working class centers that Boulanger garnered his greatest successes.

We can multiply the number of quotations from those on the left who either supported Boulangism or refused to openly or uncompromisingly oppose it. Paul Lafargue, the great socialist leader and theoretician, who in 1887 wrote a bitingly mocking article on Boulangism, also wrote to Engels that “Boulangism is a popular movement that is in many ways justifiable.” The followers of the other great Marxist if the generation, Jules Guesde, wrote that “the Ferryist danger being as much to be feared as the Boulangist peril, revolutionaries should favor neither the one nor the other, and shouldn’t play the bourgeoisie’s game by helping it combat the man who at present is its most redoubtable adversary.”

But not everyone on the left was willing to go along with or refuse to block the Boulangist juggernaut. Jean Jaurès wrote that Boulangism is “a great movement of socialism gone astray,” and the Communard and historian of the Commune P-O Lissagaray was a motive force behind the Société des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen, which was formed to combat Boulangism and defend democracy, uniting in the group socialists, republicans, students and Freemasons.

It was only later, with the publications of works by members of the Boulangist inner circle, that the close ties between Boulanger and monarchists and bankers were to be confirmed and become widely known.

And yet, the moment and movement were to end quickly and ignominiously. Standing as a candidate in Paris in January 1889, Boulanger won the election by 80,000 votes of the 400,000 cast.

A huge crowd gathered to acclaim him as he celebrated his victory at the Café Durand and pressed him to finally seize power. He refused to do so, and the government launched a legal attack on the man and the movement. Warned he would be arrested, accompanied by his mistress, Mme Bonnemains, Boulanger fled to Belgium. The movement immediately collapsed, and Boulanger and two of his closest lieutenants, Rochefort and Count Dillon, were tired and condemned in absentia for plotting against internal security.

In July 1891 Boulanger’s mistress died, and on September 30 of the same year the defeated, disconsolate Boulanger, ended his own life.

Within a few years the toxic Boulangist mix of nationalism and socialism, now leavened with overt anti-Semitism (Boulanger’s propagandist and co-defendant Henri Rochefort led the way in this regard) was to find its cause in anti-Dreyfusism; decades later variants of Boulangist national socialism were to make an even more somber appearance.