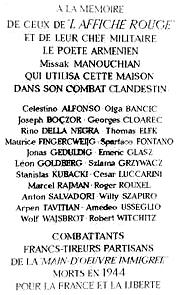

Heroes and Martyrs of the Resistance

On the afternoon of February 21, 1944, 23 members of a Communist Resistance movement, the Francs Tireurs et Partisans - Main - d'oeuvre immigrée (FTP-MOI), were executed at Mont Valerian. The one-day trial of these men and women, who were to become known as the Manouchian Group (after the leader of the Parisian section of the organization, the Armenian activist and poet Missak Manouchian), had been the subject of a huge publicity campaign in the collaborationist press. The reason for the campaign was simple: of the 23, 20 were foreigners, and of them, 11 were Jews. The goal of the publicity campaign was to use the Manouchian Group to paint the Resistance as a Communist, foreign and (more specifically), a Jewish affair. The daily France-Soir headlined its coverage of the trial with: “The trial of the 24 Judeo-Communist terrorists/The Jew Rayman and Alfonso, accomplices of Missak Manouchian, tell judges the story of the murder of Dr. Ritter.”

The campaign reached its height (and attained immortality) through the publication and posting throughout France, in the days before the execution of l'Affiche Rouge: The Red Poster. The poster asked: “Liberators?” And, below photos of derailed trains, a bullet-riddled body, and an arms cache, answered: “Liberation! By the army of crime.” More importantly, and more to the Nazi’s point, were the ten photos placed within circles identifying members of the group and their “crimes.” “Alfonso — Spanish Red — 7 attacks” “Grzywacz — Polish Jew — 2 Attacks,” “Rayman — Polish Jew — 13 Attacks.” At the apex of the inverted triangle of photos, pointed to by an arrow, were the words: “Manouchian — Armenian — Chief of the Group — 56 Attacks 150 dead 800 Wounded.”

Instead of condemning them, this poster was to live on and serve as the Manouchian Group’s memorial.

The Group fought the Germans as part of the FTP-MOI, a part of the larger Francs Tireurs et Partisans (FTP), and the continuation of the French Communist Party’s (PCF) pre-war organization for immigrant workers, Main d'oeuvre immigrée. Their actions at the beginning of the occupation consisted of carrying out sabotage of factories working for the Germans, and of aiding in the return of immigrant Communists to their occupied homelands to join the Resistance.

By summer 1941 (and the invasion of the Soviet Union) the PCF’s occasionally ambiguous positions on resistance changed, and along with propaganda work among the occupation troops, armed struggle became the order of the day. The FTP-MOI was at the heart of it in Paris.

Arson at factories producing for the Germans; derailing of trains; attacks on German soldiers, all were carried out by these soldiers of the army of the shadows. Bomb factories were set up, false papers were manufactured; clandestine presses operated in Yiddish, Italian, Spanish, Hungarian, Armenian, Romanian...

The Parisian branch of the FTP-MOI, under the direction of Missak Manouchian, earned a reputation for daring through such large-scale actions as the attempt to kill von Schaumburg, Commander of German troops of Paris, and the successful execution on September 28, 1944 of SS General Ritter, head of the hated Service du Travail Obligatoire, the German forced labor service. An idea of the extent their activities can be gathered from just one day’s activities, those of September 8, 1943 (just weeks before the group’s capture): Derailing of a train on the Paris- Reims line; the execution of two feldengendarmes in Argenteuil; two soldiers killed at the Porte d'Ivry; a sergeant killed on the rue de la Harpe; two other Germans shot at an undisclosed location.

But by the summer of 1943 the group was in trouble. It was beginning to appear that the Germans and their French auxiliaries were hot on their trail. The PCF removed most of the non-immigrant resistance, the FTP, from Paris, but left the FTP-MOI behind. By this time the entire armed Resistance in Paris consisted of several tens of immigrants (during the months from August to October 1943, they averaged 60 members, of whom 37 were combatants), one of whose leaders had cracked under torture and given the authorities the information they needed to track and capture the Manouchian Group. By November, all of its members had been captured and were interrogated and tortured in the months between their imprisonment and their trial in February 1944.

This was to be the cause of a political scandal 40 years after the war’s end, with the publication of several books on the Manouchian Group and the release of the film “Des Terroristes en Retraite.” Did the PCF knowingly abandon these foreigners to their fate? Should they have been removed from the line of fire? Or did the benefits outweigh the risks, and was it reasonable to hope that these men and women would continue to find a way to escape their pursuers?

The PCF had political reasons to keep the Manouchian Group in Paris. It was becoming clear that the Allies would eventually win the war, they needed to have their fighters in Paris, and their most effective fighters in Paris; the FTP-MOI. As proof: in the last months before the capture of the FTP-MOI, Courtois, Peschanski and Rayski, in their book Le Sang de l'Etranger, cite 40 actions in Paris and its surrounding region. Abraham Lissner, a member of the FTP-MOI, lists in his memoirs several hundred actions and articles of military material destroyed. After the capture of the Manouchian group, there was no further activity.

The argument will probably never be settled, but one thing is certain: there is no other example in the annals of the anti-Nazi resistance of such wide internationalist participation and sacrifice in a country’s resistance movement. It is in recognition of this that every year a gathering is held in their memory at the burial place of most of their members, the Parisian Cemetery of Ivry. And on their graves figure the words: “Mort pout la France.” Died for France.

The members of the group were:

Celestino Alfonso — Spaniard

Olga Bancic — Roumanian

Joseph Boczov — Romanian

Georges Cloarec — French

Rina Dell Negra — Italian

Thomas Elek — Hungarian

Maurice Fingerczwajg — Polish

Spartaco Fontano — Italian

Imre Glaz — Hungarian

Joans Geduldig — Polish

Leon Goldberg — Polish

Szlama Grzywacz — Polish

Stanislas Kubacki — Polish

Arpen Tavitian — Armenian

Cesare Luccarini — Italian

Missak Manouchian — Armenian

Marcel Rayman — Polish

Roger Rouxel — French

Antonio Salvadori — Italian

Willy Szapiro — Polish

Amadeo Usseglio — Italian

Wolf Wajsbrot — Polish

Robert Wichitz — French