thereby that it is better to spring a surprise attack on the enemy than to let him get his blow in first.

thereby that it is better to spring a surprise attack on the enemy than to let him get his blow in first.Frederick the Great once clothed his foreign policy in a garb of bad Latin. Prevenire, non preveniri, he said, meaning to imply  thereby that it is better to spring a surprise attack on the enemy than to let him get his blow in first.

thereby that it is better to spring a surprise attack on the enemy than to let him get his blow in first.

Pilsudski acted on this maxim in the spring of 1920. Dr. Vaclav Lipinski, for many years Polish ambassador in Berlin, avows this more or less unashamedly in an article entitled “The Great Marshal,” which appeared as a preface to the German translation of Pilsudski’s Memoirs. In this he wrote:

“The new year of 1920 was to bring about a radical change in the existing war situation. The Bolshevists made strenuous preparations for a surprise attack on Poland after they had defeated the armies of Kolchak, Denikin and Yudenich that opposed the Revolution. The essential objective of this surprise attack was evident; they intended to destroy Poland in order to join hands with Germany, still shaken by revolutionary fermentation, and thus light the fire of communist revolution throughout Europe. Joseph Pilsudski, who was in supreme command of the Polish forces, decided to anticipate the enemy’s onslaught by an offensive of his own, since attack is the most effective form of defence.

“Since the first information he received reported a concentration of Russian forces in the Ukraine, he resolved to deal his blow in the same direction and combine this plan with political operations far-reaching in their purpose. In order to weaken Russia and strengthen the forces of her foes, Pilsudski therefore signed on April 22, 1920, a military agreement with Petliura, the military and political leader of the Ukrainian independence movement; four days later he launched severe attacks which enabled him to destroy two Russian armies and enter Kiev on May 7.”

Lipinski’s assertion that Soviet Russia was making ‘strenuous preparations’ for war against Poland in the spring of 1920 is refuted by the fact that only very weak Russian forces were stationed on the line of her Polish frontier. On April 25, 40,000 men (Polish regulars and Petliura’s formations) advanced into the Ukraine, but the Poles had already occupied the two frontier towns of Mosyr and Rechnize on March 6.

After their occupation the Revolutionary Council of War of the Soviet Republic ordered Budyonny’s cavalry army, then in the Caucasus, to proceed to the Ukraine. But these forces were still on the march when Pilsudski launched his great offensive.

Only the scanty troops of the 12th Red Army, amounting in all to 12,000 men, were then in the

Ukraine. Further southward, in the vicinity of the Bessarabian frontier, the 14th Red Army was already involved in a series of engagements with Petliura’s troops and ‘wild’ Rumanian formations. The 12th Army was thrown back across the Dnieper, and the Poles took Kiev, which then changed its form of government for the fifteenth time since the Revolution.

The Soviet authorities did not despatch any large forces to the Polish frontier until Pilsudski opened hostilities. At the beginning of 1920 they had even offered the Poles peace terms far more favourable than those envisaged by the Entente. But Pilsudski dreamed of the ‘pre-1722’ frontiers (i.e. those obtaining before the First Partition of Poland), which would have given him a part of the Ukraine, all East Prussia, Lithuania, and White Russia, and half of Latvia for the Greater Poland on which his aspirations were bent.

As Trotsky has made clear in his work On Military Doctrine, the fact that Soviet Russia was obviously on the defensive “contributed in very large measure to the work of rallying to our side the public opinion of numerous bourgeois intellectuals as well as that of the workers and peasants.”

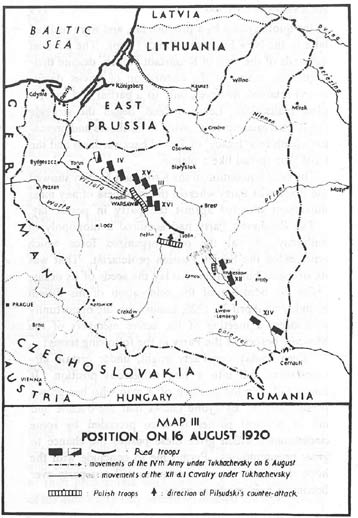

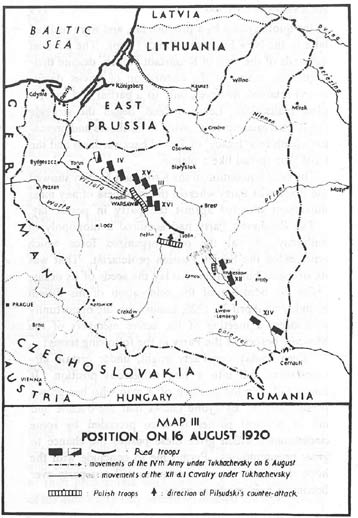

The Revolutionary Council of War decided to form two army groups for the offensive planned for the Polish campaign. One was to be employed on the ‘western front’ and to advance on Warsaw from White Russia along a route enabling it to cover its flank by the Lithuanian and East Prussian frontiers, while the other was to form the ‘south-western front,’ and march on Lublin after recapturing Kiev. The operations on this south-western front were to be co-ordinated with those on the western front.

Tuchachevsky was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the western front; Smilga accompanied him as member of the Revolutionary Council of War, with Mukievitch as Staff Commissar. The component forces of the western front included the 4th Army (commanded by Sergeyev), the 15th Army (commanded by Kork, with Lashevitch as member of the Revolutionary Council of War), the 3rd Army (Yakir) and the 16thArmy (Pyatakov as member of the Revolutionary Council of War).

The Commander-in-Chief on the south-western from. was Yegorov, who also led the 12th Army. Stalin was the member of the Revolutionary Council of War on this front, which included, in addition to the 12th Army, the 1st Calvary Army (commanded by Budyonny, with Voroshilov as Commissar) and the 14th Army (Uborevitch), which operated on the Bessarabian frontier.

In order to co-ordinate the military operations of both army groups, the Revolutionary Council of War decided that the south-western forces (with the exception of the 14th Army) should be subordinated to the Commander-in-Chief of the western front as soon as the latter had advanced as far as the meridian of BrestLitovsk. This arrangement was a compromise, for Tuchachevsky had requested the immediate subordination of both armies of the south-western front to his command, in order to ensure unity of action. But S. S. Kamenev, who was then the supreme commander of all the armed forces of the Soviet Union, decided upon this temporary solution of the difficulty, because considerable friction had existed between Tuchachevsky and the commanders of the south-western front (Yegorov, Stalin and Voroshilov) ever since the Czechoslovak Insurrection in the summer of 1918.

The Revolutionary Council of War ordered troops from almost all parts of Russia to the Polish front as soon as Pilsudski opened hostilities. Until April 1920 practically no forces had been sent to this area.

From December 1919 to April 1920 the region destined to become the western front was occupied only by three infantry divisions and three brigades; on the south-western front, i.e. in the sector where Pilsudski claimed to have noticed such large concentrations of forces that he deemed his preven ire to bean indispensable measure of national defence, there was, in January 1920, only a single infantry division. In subsequent months the following formations were sent to the future Polish theatre of war from the former northern front, the Ural military district, the Tula military circuit, the eastern, Caucasus and southern fronts:

To the western front two infantry divisions and two infantry brigades in April, five infantry divisions and two infantry brigades in May, three infantry divisions and three cavalry brigades in June, making a total of ten infantry divisions, five infantry brigades and three cavalry brigades.

To the south-western front five cavalry divisions in April (Budyonny), and three infantry divisions in May and June.

These figures are the best refutation of any assertion that the Soviet Republic cherished offensive intentions against Poland before Pilsudski began hostilities.

Tuchachevsky has given us the following sketch of Soviet Russia’s situation at this time in his work The Advance beyond the Vistula, which is an abbreviated version of the series of lectures he delivered at the War Academy from February 7-10:

“Kolchak had been finished off in the east and Denikin in the Caucasus. Wrangel’s base ‘of operations in the Crimea was the only territory still occupied by the Whites. All operations in the north and west were terminated, with the exception of those on the Polish front. A peace treaty had already been concluded with Latvia. Poland’s action therefore came at a time that was comparatively favourable to us.”

Although the greater number of Tuchachevsky’s forces were still on the way to him on May 20, he launched an attack on Smolensk on that day. Pilsudski maintains in his book The Year 1920, written as a reply to Tuchachevsky’s work above-mentioned, that in this May offensive “Tuchachevsky’s principal mistake (which doomed his great plans to failure in advance), was based on his erroneous estimate of his own and his opponent’s forces, which he made without taking any account of his opposite number who commanded the troops on the other side.”

This criticism shows that Pilsudski mistook the objectives Tuchachevsky set before him when he made his advance in the Smolensk area. He did not desire to force a decision there, and indeed could not have done so, since he had only received half the troops assigned to his command. His real aim was to relieve the pressure on the south-western front in order to permit the recapture of Kiev and the advance of the 12th and Budyonny’s armies on Lublin, so that the forces of the south-west would not be too far from his left flank when he began his impending western front offensive.

Tuchachevsky achieved this minor result with his May offensive, for while he was fighting heavy rearguard actions in the north, Yegorov counter-attacked on June 5. Budyonny’s cavalry broke through the enemy’s lines, and the 12th and 14th Armies followed in his wake. The Polish forces beat a precipitate retreat; on June 8 Budyonny took Zhitomir. Kiev was recaptured on June 12; on June 25 Brody was occupied. But meanwhile the situation on the south-western front had grown somewhat critical, for Wrangel had started a victorious northward advance from the Crimea on June 6 and was thus diverting reinforcements from the south-western front since they had to be sent to deal with him.

By the beginning of July Tuchachevsky had concentrated sufficient forces to take the offensive. The 48,837 infantry and 3,456 cavalry at his disposal when he made his first advance in May, had now reached totals of 80,942 and 10,521 respectively, distributed as follows:

The 4th Army comprised about 14,000 infantry and cavalry, the 15th about 26,000, the 3rd about 20,000, and the 16th about 25,000. There was also the 57th infantry division, composed of some 6,000 infantry and cavalry, which was a ‘special division’ operating independently on the left flank of the south-western front. This was afterwards known as the Mosyrz Group, because of its advance in the direction of Mosyrz.

The total artillery armament of the south-western front consisted of 395 guns.

Tuchachevsky stated that his forces also included 68,725 men for whom no arms were available, so that he could employ them only as replacements for front wastage.

Pilsudski estimated the enemy forces opposing him in White Russia at the higher figure of about 200,000 men. The statistics of the equipment and commissariat departments of the General Staff of the Soviet Union give a total of 795,645 men and 150,572 horses employed on the western front during the Polish campaign, and Pilsudski assumes that the Red Higher Command were able to send rather more than 25 per cent of the total man-power of this front into action. It must be noted, however, that he reckoned the percentage of men in the Polish Army that could go into action as only from 12 to 15, “on account of their inferior discipline and Polish weakness and cowardice.”

Pilsudski estimates the forces commanded by General Szepycky on the same sector as Tuchachevsky at not more than 100,000 to 120,000 men. He also believes that he had between 120,000 and 180,000 under his own command when he started his counter-offensive in August, this great latitude in his estimate being explicable, as he complainingly asserts, “by the great confusion prevailing at the time.” But undoubtedly it would be wise to treat all the statistics of both belligerents with the greatest reserve.

In June Pilsudski wanted to “liquidate Budyonny quickly,” because Tuchachevsky’s reverse in May led him to believe that he need not anticipate an immediate Russian offensive in the north. He therefore transferred considerable forces to the south.

“I did not attach any great importance to Budyonny’s cavalry,” he wrote, “and thought their victories in previous Soviet theatres of war were due rather to internal disintegration of their opponents’ forces than to any real value in their fighting methods.” Consequently Pilsudski did not devote his attention to his northern front again until after all his efforts to defeat Budyonny had failed, i.e., shortly before the opening of Tuchachevsky’s offensive. He then left the operations against Budyonny in charge of Rydz-Smigly, “who, like almost everyone else at that time, did not take the enemy’s cavalry seriously.”

On July 4 Tuchachevsky launched an attack in the sector between the Beresina and the northern Dvina. He massed the 4th, 15th and 3rd Armies on his right wing, thus obtaining an enormous numerical superiority at the point he had chosen for the centre of his operations. Attacking 30,000 Poles with 50,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry (the 2nd Cavalry Army, commanded by Gay), he broke through the Polish front, and the Soviet troops then advanced westwards in the direction of Warsaw.

Vilna was taken on July 14; on the 19th the ancient fortress of Grodno fell; on the 27th the Russians were in Ossovetz. Pilsudski then thought to deliver a counter-stroke against Tuchachevsky’s left flank from the Brest-Litovsk area; on July 30, General Sikorski, who commanded the forces defending the fortress, informed him that he could hold out for ten days. But Brest-Litovsk fell on August 1, two days later, and Bialystok was taken the same day.

Pilsudski has given us the following description of the advance of the Red Armies and the impression they made on the Polish forces and the entire Polish Republic:

“Tuchachevsky’s troops advanced continuously as soon as the way was clear for the 4th Army and the cavalry. One day they were only about 20 kilometres away from Warsaw and its environs, i.e., only a normal day’s march. This unceasing, wormllke advance of a huge enemy horde, which went on for weeks, with spasmodic interruptions here and there, gave us the impression of something irresistible rolling up like some terrible thunderclouds that brooked no opposition. The pressure of this approaching thunderstorm broke the joints of the machinery of state, weakened all our characters and took the heart out of our soldiers. By this march on Warsaw, which originated undoubtedly in his will and energy, Tuchachevsky gave proof that he had developed into a general far above the average commonplace commander.”

Pilsudski “then came to a decision contrary to all logic and the sound principles of warfare.” He withdrew a number of formations from the Polish southern front, leaving only two-and-a-half infantry divisions to oppose the 12th Red Army and Budyonny’s cavalry. He planned his counter-offensive on the theoretical assumption that these Soviet forces did not exist.

In this fashion he concentrated over twenty divisions against the Russians of the western front, fifteen of which were destined to play the passive role of defenders of Warsaw. His task was rendered possible and lightened by the fact that, despite the boycott initiated by the German workers, considerable artillery material had reached him from France.

Pilsudski denies to the French any part in his victory over the Soviet forces, and ascribes all his successes to the energy and skill displayed by himself and his Polish co-operators. “It was owing to the extraordinary energy evinced by General Sosnovski in the Warsaw area that the artillery came into the picture in a strength hitherto unknown in our war. It approximated closely to the ideal evolved by the experiences of the World War. With this artillery we were able to develop a proper drum-fire.”

When the French artillery served by French officers under the command of General Sosnovski had relieved Pilsudski of the greater part of his anxiety for Warsaw, he concentrated five and a half divisions in the Deblin-Lublin area, with the intention of despatching them against Tuchachevksy’s unguarded left flank in the direction of Brest-Litovsk.

Despite their continuous advance, the Russians on the western front were in a critical position. Both wings of the main mass were left in the air. The 4th Army, which operated on the right flank in conjunction with Gay’s strong cavalry forces and on August 5 had received orders to turn off southwards and advance in the Medlin-Warsaw direction, continued its march in a north-westerly direction towards the Polish Corridor, thereby losing touch with the Higher Command. In his book Pilsudski quotes the witticism of a French officer, who said that “instead of reaching Warsaw, the 4th Russian Army fought against the Treaty of Versailles rather than against Poland.”

At dawn on August 16 Pilsudski launched his counter-offensive from the Deblin-Lublin area. “This illogical operation which ran counter to all sane principles of warfare” led to complete success because the forces of the Red south-western armies failed to come into action. Pilsudski found his attacking forces opposed only by a few thousands of men belonging to the ‘Mosyrz Group,’ which was broken up into very small units forming a broad but very loose cordon against Deblin-Lublin. These retired in disorder when the Polish divisions fell upon them.

Pilsudski’s troops met with practically no resistance for the first three days of their offensive. The marshal, who took personal charge of operations, “suspected traps everywhere,” “thought he was in some enchanted fairyland” and “saw mysteries and riddles everywhere.”

On August 18 Pilsudski was back in Warsaw, where he gave orders for a general advance along the whole line. On the same day Tuchachevsky ordered a general retreat, but “the commander of the 4th Red Army disobeyed orders and began a further advance in the direction of East Prussia.” The remaining Red Army formations streamed back in disorder to their original positions between the Beresina and the northern Dvina, while the 2nd Cavalry Army and parts of the 4th Army that had advanced too far westwards were forced on to East Prussian soil and interned in Germany until the end of hostilities.

An armistice came into force on October 12, when the Soviet forces were in occupation of the line that now forms the frontier between the two countries, and on March 18, 1921, a peace treaty between Poland and Soviet Russia was signed at Tallinn.

Tuchachevsky attributes the collapse of the Russian offensive to the fact that the forces of the south-western front in general and the 1st Cavalry Army in particular were induced by Stalin and Voroshilov to disobey the Commander-in-Chief’s orders. Instead of acting on his instructions to concentrate in the Samosz-Hrubezov area, in readiness for an advance on Lublin, they continued their march on Lwow. He sums up the situation at the opening of the Polish offensive as follows:

“The Poles effected a daring but sound regrouping of their forces; leaving Galicia to take its chance, they concentrated all their strength for their main attack on the decisive western front. At that critical moment our troops were dispersed and moving in various directions. Our left wing, i.e. the groups composing our southwestern front, was a continual source of anxiety to the western front in this respect. Anticipating that the Cavalry Army would be at the disposal of the western front at any moment and that we would be able to effect a junction with it, we planned the formation of a strong group, which was to march on Lublin while we concentrated the main forces of the 12th Army and 1st Cavalry Army there. If this had been done in good time, our army group there would have threatened danger to the Poles, in which case they would not have dared to risk an attack from the Deblin-Lublin area, because they would then have been in a very critical position. Even if the advance of the Cavalry Army had been to some extent delayed, the Polish forces would still have been exposed to the danger of complete and inevitable defeat, because our victorious cavalry forces would have taken them in the rear.”

In amplification of Tuchachevsky’s statement we must add that according to Pilsudski there were only 16,000 Polish troops to bar the way of the 35,000 men composing the 12th Army and the Cavalry Army, if they had advanced on Lublin. But after the fall of Brody on June 25 Stalin and Voroshilov gave orders for the cavalry to turn off in the direction of Lwow. “Worst of all,” observes Tuchachevsky, “our victorious Cavalry Army became involved in severe fighting at Lwow in those days, wasting time and frittering away its strength in engagements with infantry strongly entrenched in front of the town and supported by cavalry and strong air squadrons.”

Budyonny even continued his senseless attacks on the Lwow fortifications for five days after the opening of Pilsudskj’s offensive. He did not order his weakened forces to march on Lublin ‘until it was too late.’

Pilsudski, who was Tuchachevsky’s great opposite number and conqueror in the Polish theatre of war, makes the following criticism of his opponent’s strictures on the commanders of the south-western front:

“If Tuchachevsky counted on co-operation with the Russian forces in the south, he ought to have awaited the development of their operations there and supported them when necessary. But as soon as he made up his mind to advance to the Vistula without reckoning on support from the south, he had no right to complain later on of lack of that same support.”

Herein Pilsudski overlooks the fact that Tuchachevsky was not in supreme command of all the Soviet forces, and was thus unable to direct the movements of the armies of the south-western front in accordance with his own desires. By virtue of the agreement reached between him and S. Kamenev, the forces on the south-western front were to be subordinated to him after the capture of Brest-Litovsk; although his troops took this fortress on August 1, it was not until August 11 that Kamenev instructed their commanders “to regroup their formations and despatch the Cavalry Army to Zamosc-Hrubeszov at once.” Yegorov’s 12th Army was placed under Tuchachevsky’s command on August 13, but, like the Cavalry Army, it was induced by Stalin and Voroshilov to disobey these orders.

Apart from the above reservations, Pilsudski is of opinion that a concentration of the cavalry in the Zamosc-Hrubeszov area would have brought his whole plan of operations to naught. “The elimination of the strong battle force that the enemy possessed in Budyonny’s cavalry was a basic condition for the successful execution of my plan,” he writes. “Our south-western front had to be abandoned to its fate. I did not deem it impossible for the cavalry forces which had done us so much damage to resume their forward movement. Their correct line of march was the one which would have brought them nearer to the Russian main armies commanded by Tuchachevsky, and this would also have threatened the greatest danger to us. Everything seemed black and hopeless to me, the only bright spots on the horizon being the failure of Budyonny’s cavalry to attack my rear and the weakness displayed by the 12th Red Army.”

Pilsudski began his offensive with only these “bright spots on the horizon.” But he admitted in advance that he “realized that the weakened forces of the southern front would not be in a position to hold the enemy opposing them, and therefore instructed the 6th Army to retreat slowly on Lwow in the event of any pressure from the Russians. But in the event of Budyonny turning northward, I ordered our cavalry to co-operate with the best infantry division in those parts in pursuing him and to delay his advance at any cost.”

Even Tuchachevsky did not lay such strong emphasis on the decisive importance of an attack by the Russian cavalry on the flank of the Polish shock troops. Pusudski planned to entice Budyonny still further into the environs of Lwow by the retreat of his own troops, but he also gave them strict orders to delay the Russian cavalry leader’s northward advance at any cost.

Pilsudski goes still further, however. In view of the danger threatening him, he resorts to “an extremely daring action.” “By withdrawing the 1st and 3rd Legionary Divisions from the southern front,” he writes, “I opened the way for Budyonny’s cavalry to attack us.”

This was, in fact, the “illogical” element in Pilsudski’s plan of attack “which ran counter to all sane principles of warfare.” But on August 15 he was able to note with triumph that “Budyonny’s Cavalry Army developed activities in the south, and our 6th Army began to fall back on Lwow under the pressure he exercised.” These operations guaranteed him more or less against the risk of the Red Cavalry falling upon his flank and rear, so that he was able to begin his offensive on August 16 with an easier conscience.

What are the arguments with which the commanders of the Russian south-western front—Stalin, Voroshilov and Yegorev—defend their action?

At first they made no attempt to defend it. It was not until Stalin was involved in his struggle with Trotsky some years later that he asserted that the whole plan of campaign drawn up by Tuchachevsky and Trotsky was utterly wrong in its conception and that “it was based on a purely military point of view which ignored the political aspect.” His complaint was that this plan of campaign, based on an encircling of Warsaw initiated

from the north, involved a march through agricultural areas, whereas the great industrial districts lay in the line of an advance through the territory to the south and south-west of Warsaw.

But Stalin’s theory is not exactly strengthened by the fact that Lwow put up a stiff resistance to the advance of the Red Armies of the south-west, despite its large proletarian population. Moreover, any Red Army advancing on Lodz across territory south of Warsaw would have been in danger of flank attacks from north and south, i.e. from strongly fortified Warsaw and from the fortress of Cracow, which would have gripped it as if between pincers and crushed it.

Tuchachevsky’s plan was based on the idea that the wide sweep of his right wing would enable it to derive support from a friendly Lithuania and a Germany containing a strong working-class movement. But in any case a subordinate commander cannot permit a whole plan of campaign to fail merely because he does not approve of it and prefers to wage a war of his own.

In reality neither Stalin nor Voroshilov were motivated by their desire to apply “scientific revolutionary theories” in the year 1920. The real reason for their actions was the old feud and rivalry between Tuchachevsky and the commanders of the south-western forces, to which we may add the old guerilla elements in their blood. Their plan to capture Lwow was not evolved until after the fall of Brody. “Lwow is so near—barely a hundred kilometres off our route,” they said. “Come on! Let’s take it!”

Tuchachevsky, in his book, draws a comparison between the conduct of the chiefs of the south-western front and the behaviour of General Rennenkampif at the battle of Tannenberg in 1914. He amplified this comparison in greater detail in his lectures to the War Academy and accused those leaders of deliberate treachery. At that time, however, Voroshilov was only an insignificant commander of a military district in the Caucasus.

There are, indeed, certain resemblances between General Rennenkampif’s behaviour in 1914 and the conduct of the chiefs of the south-western front, who are today the heads of the Soviet Government and army. In August 1914 the Russians invaded East Prussia with two armies, with a northern one under Rennenkampif’s command, which entered German territory from the east, while Samsonov led the forces attacking from the south. The German Higher Command decided to denude the front opposed to Rennenkampif of practically all its troops, in order to try for a decisive victory over Samsonov in the south. General Max Hoffmann, who played a leading part in the battle, gives the following description of the critical situation of the German forces and Rennenkampif’s conduct, which made the German victory possible, in his book: The War of Neglected Opportunities:

“No one, however ignorant of the art of war, could fail to see that it was impossible to transfer two army corps from the northern to the southern front; no one could assume that General Rennenkampif would remain inactive when he received news of the German retreat on the morning of the 21st. Hindenburg’s predecessor, Prittwitz, could not have stood the strain on his nerves caused during the next few days by that vital question: ‘Will Rennenkampif attack or not?’

“General Samsonov sent Rennenkampif order after order to pursue the Germans, but Rennenkampif’s army persisted in its incomprehensible immobility. The German commanders therefore despatched two more army corps to the southern front, in order to use them for the decisive battle against Samsonov.

“The question naturally arises why Rennenkampif refused to attack despite the repeated orders Samsonov sent him by wireless. The slightest advance on his part would have prevented the Tannenberg catastrophe.

“I should therefore like to mention the rumour that Rennenkampif refused his assistance on the grounds of personal enmity for Samsonov. That such a personal enmity did exist between the two men I know for a fact; it dated from the battle of Liao-Yang in the Russo-Japanese War, when Samsonov undertook the defence of the Yentai coal-mines with his Siberian Cossack division, but was compelled to evacuate them because Rennenkampif’s detachment on the Russian left wing remained inactive despite repeated orders. Witnesses have told me of the hot words that passed between the two leaders at Mukden railway-station after the battle.”

The resemblances between the behaviour of Rennenkampif, which caused the utter annihilation of a Russian army, and the conduct of the chiefs of the southwestern front, which led to the loss of an entire campaign are certainly most startling. But the factors which finally made Pilsudski’s victory possible may be traced to a source which lies deep below all military considerations.

The plan of the Russian advance on Warsaw was based upon the fundamental idea of revolutionary fraternization with the Polish workers and the excitation of revolutionary conflicts in Germany. Tuchachevsky put the question : “Could Europe back up this socialist movement, which the march on Warsaw constituted with a revolution in the west?”

He gave the following answer:

“Events say ‘Yes.’ The German workers manifested open opposition to the Entente. They sent back the railway-wagons filled with arms and food which France had sent to Poland’s aid; they refused to unload the French and British ships sent to Danzig with arms and munitions; they caused accidents on the railways, etc. From East Prussia came hundreds and thousands of volunteers, who formed a German rifle brigade under the banner of the Red Army. In England the working classes were also in the grip of a very active revolutionary movement.

“After a war has been lost it is naturally easy to discover political mistakes and blunders. But a ‘revolution from without’ was a possibility. Capitalist Europe was profoundly shaken, and perhaps the Polish War might have acted as a connecting link between the October Revolution and a revolution in western Europe, if our strategic blunders and our defeat on the battlefield had not made it impossible.

“Our task was difficult, daring and complicated; but the solution of world problems is never an easy task. There is no doubt that the revolution of the Polish workers would have become a reality if we had succeeded in depriving the Polish bourgeoisie of its bourgeois army. The conflagration caused by such a revolution would not have stopped at the Polish frontiers; it would have spread all over Europe like the waters of a wild mountain torrent.

“The Red Army will never forget this experience of ‘revolution from without.’ If ever Europe’s bourgeoisie challenges us to another war, the Red Army will succeed in destroying it. In such a case the Red Army will support and spread the revolution in Europe.”

The error in Tuchachevsky’s calculations is to be found in his over-optimistic view of the revolutionary situation in Poland, or, to put it better, his underestimate of the national antagonism between the Polish race and the Great Russians, who had been their national oppressors for more than a century. This error does honour to Tuchachevsky, for it arises from his revolutionary zeal.

E. N. Sergeyev, who commanded the 4th Red Army, was definitely sceptical in his judgement of the revolutionary sentiments of the Polish workers. In his book From Dvina to Vistula he wrote:

“The occupants of political chanceries a long way from the front were the only people who seriously believed in the possibility of a Polish Revolution. We in the army had little faith in it, and obviously our attempt to form a Polish Red Army in Bialystok is proof enough of the fact that our sources of information gave us too optimistic a view of the situation in Poland.”

The ‘political chanceries’ must include Lenin’s own ‘chancery’ and the Comintern, which he and Zinoviev then directed.

Pilsudski gives detailed attention in his book to the question of ‘Revolution from Without’ as expounded by Tuchachevsky.

“Poland,” he writes, “was overwhelmed for a hundred and twenty years by the blessings of alien rule, which it hated passionately because it was maintained by the power of alien bayonets. When Tuchachevsky stretched out his hand to grasp the centre of our national life, Warsaw, our capital; when his bayonets had done their work, the only abiding-place for the Soviet Revolution was on their points, for within Poland it had no value. Yet all the calculations of Tuchachevsky and his country were based on the idea that the bayonets need only give the word, and then there would be a chance for the Soviet Revolution to develop its power in the land it had invaded.”

The truth, in any case, must lie somewhere between the views formed on the one hand by the Bolshevists, including Tuchachevsky, and by Pilsudski on the other. Undoubtedly the majority of the Polish peasants, almost all the urban lower middle classes, and even a part of the working classes of Poland sympathized with the nationalistic ideas of the Polish bourgeoisie. Trotsky, who knew Polish history and the mentality of the Polish proletariat well enough to foresee this outcome, opposed the idea of extending the invasion beyond the ethnographical frontiers of Poland, but he was the only member of the Bolshevist Central Committee to champion this point of view. In his work On Military Doctrine he goes into some detail on this problem of ‘Revolution from Without,’ as exemplified by the Polish campaign:

“We over-estimated the revolutionary character of the Polish internal situation. This over-estimate found expression in the extraordinary aggressiveness—or, more correctly, in the failure of that aggressiveness we might have displayed—of our military operations. We just pushed on all too carelessly, and everyone knows the consequences: we were beaten back. In the great class war now taking place, military intervention from without can play but a concomitant, co-operative, secondary part. Military intervention may hasten the denouement and make the victory easier, but only when both the political consciousness and the social conditions are ripe for revolution. Military intervention has the same effect as a doctor’s forceps; if used at the right moment, it can shorten the pangs of birth, but if employed prematurely, it will merely cause an abortion.”[1]

The march on Warsaw was unable to bring about a revolution in Central Europe because the fact that centuries of oppression at the hands of the Great Russians had left the Polish proletariat not yet sufficiently mature for revolution, coincided with the military blunders associated with the names of Stalin, Voroshilov and Yegorov.

At the moment when the troops of the Red Army crossed the Vistula, the revolutionary centre of gravity was not on that river, but on the Spree and in the Ruhr; it had leapt from Warsaw to Berlin. The internal hypotheses required for a decisive revolutionary conflict between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie had matured in the Germany of 1920. Field-Marshal von Blomberg reviews the situation then existing in Germany in his preface to the German translation of Pilsudski’s Memoirs [Memoirs of a Polish Revolutionary and Soldier.] in the following words:

“The Russo-Polish War is not merely a matter of interest to soldiers. Its result has a universal historical significance. Its importance for Germany can hardly be over-estimated, for in this war something more than Polish national liberty and the continued existence of the Polish Republic was at stake. In its final aspect it was a question whether the Bolshevist Revolution should penetrate further into Europe and thus impose its rule on Germany as well as other countries. In the Germany of 1920 many of the preliminary conditions essential for such a revolution existed. Poland after a hard struggle hurled Bolshevism back to the land of its birth and erected a strong barrier against its further westward advance. Thus Poland saved all Europe, including Germany, from collapse.”

Lenin was in favour of the military offensive because the march on Warsaw might have hastened the collapse of capitalist Europe and made easier the victories of the German and other European proletariats. After the defeat of the Soviet forces before Warsaw he gave the following explanation in an address delivered on October 2, 1920, at the celebration of the Trade Union Day of the leather industry workers:

“The Versailles Peace Treaty and the whole international system resulting from the Entente’s victory over Germany, would have been convulsed if Poland had become a Soviet State and the Warsaw workers had received from Soviet Russia the help they awaited. That is the reason why the advance of the Red Armies on Warsaw developed into an international crisis. It was only a question of a few more days of victorious advance for us, and then we should not have merely captured Warsaw; we should also have shaken the Versailles Peace Treaty to its foundations. That is the international significance of our war with Poland.”

[1] In his Official History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Pepov gives the following exposition of Trotsky’s standpoint:

“Trotsky would now have us believe that he opposed the march on Warsaw because he foresaw its disastrous consequences. He even presumes to draw a parallel between Brest-Litovsk (the Peace Treaty of 1918) and Warsaw (1920), alleging that Lenin warned the Party of the danger in 1918 and he (Trotsky) did the same in 1919. In reality Trotsky was not opposed to the march on Warsaw on the ground that he considered our forces inadequate, but because his social democratic prejudices made him averse to the idea of imposing ‘revolution from without’ on any country. In July 1920, the Central Committee rejected Trotsky’s anti-Bolshevist, Kautskyist proposals in the most definite fashion.”

But today Stalin advocates that very point of view which Pepov attributes to Trotsky. We may remember his conversation on March 3, 1936, with Howard, the president of the American press syndicate known as the Scrips-Howard newspapers, from which I quote the following:

“HOWARD: Are you not of opinion that there may be wellgrounded fears in the capitalist countries that the Soviet Union might decide upon a forcible conversion of other nations to its political theories?

“STALIN: There is no reason for such fears. You are greatly mistaken if you think the men of the Soviet would ever want to change the state of any other country by any means, let alone by force.

“HOWARD: Does this declaration of yours imply that the Soviet Union has in any way renounced its plans and intentions to bring about a world revolution?

“STALIN: We never had any such plans or intentions.

“HOWARD: It would seem to me, Mr. Stalin, that quite a different impression has been current in the world for a long time. “STALIN: That is the result of a misunderstanding.

“HOWARD: A tragic misunderstanding?

“STALIN: No a comic one. Or perhaps a tragi-comic one. It is nonsense to try to make revolution an article of export. If a country wants a revolution, it wants to make it for itself; and if it doesn’t want one, there can be no revolution. To state that we want to bring about revolution in other countries by meddling in their manner of life is to assert something which is not true and which we have never put forward.”