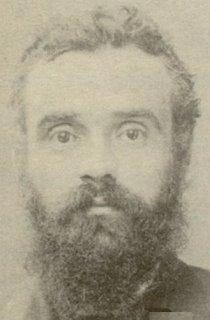

Georges Darien 1890

Source: Biribi, Paris, Albert Savine, 1890;

Translated: for marxists.org by Mitchell Abidor;

CopyLeft: Creative Commons (Attribute & ShareAlike) marxists.org 2010.

A comrade in the disciplinary battalion, the “Biribi” of the title of Darien’s masterpiece, dies in a hospital, and is buried in two crates nailed together. The narrator, Froissard, gives vent to a cry of rage typical of late nineteenth century French anarchism.

Oh poor little soldier. You who died calling out for your mother; you who, in your delirium, saw before you the vision of your hut. You will sleep there at age twenty-three, eaten by the worms of the land where you so suffered; where you died, alone, abandoned by all, with no one to calm your final fears, with no other hand to close your eyes than that of a nurse who screamed at you during the night when your desperate cries troubled his sleep. I know full well why your illness became incurable. I know better than the doctor who dried out your wasted body why you are laying in the grave. And I pity you with all my heart, poor victim, just as I pity your mother who perhaps is waiting for you, counting the days, and who will receive a dry and gloomy death notification.

But then again, no: I don’t feel for you, corpse! But then again, no: I don’t feel for you, mother! I don’t feel for you, do you hear me! No more than I feel for the sons who kill the bloodthirsty, no more than I pity the mothers who cry over those they sent to their death. Oh you mad women who give birth in suffering only to hand the fruit of your womb over to the Minotaur who eats them. Don’t you know that female wolves allow themselves to be massacred rather than abandon their cubs, and that there are animals who die when their little ones are taken from them? Don’t you understand that if you didn’t have the luck to be sterile you would have been better off tearing your sons apart with your own hands than to raise them to age twenty one and then cast them into the claws of those who turn them into cannon fodder? Don’t you have nails at the tips of your fingers to defend your sons? Don’t you have teeth to bite the hands of the cursed killers who steal them from you? You allow this to be done to you; you don’t resist. And then on the dark day of the tragedy you want us to have pity for you when your child’s bones, fallen in a distant land, are gnawed at by hyenas and whiten under the sun of abandoned cemeteries. You want us to pity you and venerate your tears? Sorry, but I won’t commiserate with you for your sufferings, and your sobs will leave me cold. For I know that you won’t soften with your tears the idol who demands your sons’ blood; for I know that you will suffer in fear as long as you won’t have torn down with your own hands, as long as you won’t have torn off the gaudy mask behind which his hideous face is hidden. And if you don’t believe me, mother who the corpse lying there cried out for for three nights, come here. Speak softly to him and hear how he answers your heart, if your heart is capable of understanding him. And you’ll see if he doesn’t tell it that he owes his death to you, and that it is to what killed him that here at his grave was delivered, like an ironically macabre slap in the face to your weakness, the panegyric of an idiot.

That evening I meet Lecreux. In the middle of a circle of fifteen or twenty men who listen with their mouths hanging open, he reads and rereads his eulogy. The applause rains down.

“That was terrific!”

“You should have heard it at the cemetery. What an effect it had.”

One of them sees me and asks me:

“That was really good, right Froissard?

“Shit!”