Revolutionary France |

The French Revolution began in the domain of philosophy and social theory. French materialist philosophy, social theory and socialist ideas were significant influences on the development of Communism and major contributors to Marx’s ideas. The following writers of Pre-Revolutionary France are significant:

- The Rationalist philosopher and mathematician Rene Descartes (1596-1650), materialist philosopher Pierre Gassendi (1592-1655);

- The sociologist and political philosopher Charles Montesquieu (1689-1755)

- founder of the "Physiocrat" School of political economy François Quesnay (1694-1774);

- sensationalist and political theorist François Voltaire (1694-1778);

- social critic, founder of linguistics and educational theorist Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), whose ideas the French Revolution tried to put into practice;

- leader of the Encyclopaedists and materialist Denis Diderot (1713-1784), sensationalist Etiènne Condillac (1715-1780), mathematician and sensationalist Jean le Rond d'Alembert (1717-1783), Physiocrat Jean Condorcet (1743-1794);

- The mathematician and determinist Pierre Simon de Laplace (1749-1827), proponent of social roots of character Claude Helvétius (1715-1771), materialist philosopher Paul Holbach (1723-1789), and

- The socialist Claude-Henri Saint-Simon (1760-1825) was among the first to outline the ideas of socialism.

Marx gives the following analysis of the history of French Materialism & Communism in The Holy Family, 1845

In his Lectures on the History of Philosophy, Hegel presents the following summary of French Philosophy, 1830.

The French Revolution of 1789

The Great French Revolution of 1789 not only overthrew the monarchy in France, but ultimately led to the destruction of the Old Order across Europe. (See Babeuf and the Conspiracy of Equals). Analysis of the French Revolution and the numerous upheavals which followed it, were a central concern of all the nineteenth century Marxists.

In A Short History of the French Revolution for Socialists, Belfort Bax presents the analysis that Marxists made of the French Revolution in 1890, also

Jean-Paul Marat. The People's Friend, Bax 1900.

Babeuf and the Conspiracy of the Equals, Bax 1911.

Socialist History of the French Revolution, Jean Jaurès 1901.

Interpretations of the French Revolution, George Rudé 1961.

See the French Revolution History Archive.

The earliest utopian socialists were French:

Morelly was an early Utopian socialist, about whom little is known.

François Charles Fourier (1772-1837) was a French socialist much admired by Marx.

Étienne Cabet (1788-1856) inspired Utopian socialist settlements in America.

Positivism, on the other hand, was the dominant current of bourgeois philosophy after the Revolution. The founder of positivism was Auguste Comte (1798-1857). The economist Léon Walras (1834-1910) was one of the founders of modern economic science (as opposed to “political economy”) by applying the ideas of the ‘second positivism’ to economy, and the positivist mathematician and physicist Henri Poincaré (1854-1912) was one of the first to deal with the problems of epistemology being thrown up by modern physics (the subject of Lenin’s Materialism and Empirio-criticism).

Foremost among the opponents of positivism was Louis-Auguste Blanqui (1805-1881), the founder of Communism.

See also the archive of another revolutionary of this period: Armand Barbès.

In left-wing of French political economy was Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1803-1865), the founder of anarchism.

See the Anarchism Subject Archive, including James Guillaume, Ravachol, Mikhail Bakunin (though Russian, did much of his work in France).

Marx-Engels Letters on France.

Writings of Marx & Engels on France.

The First International in France

When the First International was founded in 1864, its contacts in France were Proudhonists, who wanted to confine the International to study groups reading the works of Proudhon. Later the French section expanded and was a participant in the Commune.

See First International History Archive.

After the fall of the Paris Commune, France became the centre of opposition to Marx within the International from Anarchists.

See The Conflict with Bakunin.

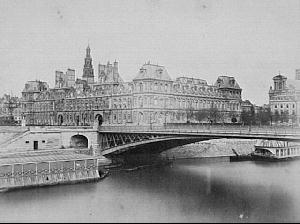

The Paris Commune of 1871

When the workers of Paris seized power in 1871, this was the first working class revolution in history to succeed in gaining power, albeit for only a few weeks. See The Paris Commune History Archive, including:

- Timeline of Events in the M.I.A. History Archive;

- Overview of the Commune in the M.I.A. Encyclopedia;

The Civil War in France, includes Marx's major writings on these events.

History of the Paris Commune of 1871 was written by Henri Lissagaray, a participant in the Commune and translated by Eleanor Marx.

Escape from Post-Commune France, is a personal account of her experiences by Jenny Marx.

Marx's French sons-in-law

Despite Marx's personal dislike of Frenchmen, all three of his daughters fell in love with French men: Jenny Marx married Charles Longuet, Laura Marx married Paul Lafargue and at age 16, Eleanor fell in love with Henri Lissagaray but was forbidden by Marx to marry him, later marrying the Englishman Edward Aveling.

See the Paul Lafargue Archive.

Anarchism in France

Anarchism can be said to have originated in France (though Spain would have a claim as well). See the following:

- Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1803-1865), the founder of Anarchism;

- Mikhail Bakunin Archive (1817-1876), the Russian nobleman who was won to anarchism while in exile in France;

- James Guillaume (1844-1916), student of Bakunin, anarcho-syndicalist;

- Ravachol Archive (1859-1892), violent anarchist executed for murder and grave-robbing;

- Emile Henry (1872-1894), anarchist terrorist;

- Zo d'Axa (1864-1930), artist and writer;

- Pierre Monatte (1881-1960), revolutionary syndicalist;

Eugene Lanti (1879-1947) was a French Communist who developed radical ideas about “a-nationalism.”

The PCF

In 1920, the French Socialist Party decided to affiliate to the Comintern and the French Communist Party was established. The PCF remains to this day a significant force in French politics.

See PCF History Archive.

The 1960s

One of the most traumatic events to shake post-war France was the Algerian Revolution of 1959 which triggered a crisis in France.

See Algeria and the defeat of French Humanism

The Algerian crisis had a significant effect on how the student uprising and General Strike of Paris May 1968 and the political developments in France after 1968.

See France – the struggle goes on, Tony Cliff August 1968;

New Passions and New Forces, Raya Dunyevskaya 1973;

Interview with Simone de Beauvoir, 1976;

The Turn in the World Situation (1968 onwards), Pierre Frank 1969.

Trotskyism in France

Trotsky wrote important articles on the situation in France during the period when the Comintern policy was for “Popular Front”:

- A Program of Action for France (1934).

- Romain Rolland Executes an Assignment (1935).

- Whither France? (1936).

During the Second World War, the Trotskyist movement played an important role in the Resistance, despite being caught between the Stalinists on one side and the Nazis on the other. See With the Masses, Against the Stream: French Trotskyism in the Second World War by Ian Birchall.

See also the archives for: Pierre Broué, Pierre Frank and Michel Pablo.

See The Manouchian Group – an archive about a group of mainly foreign communists, remembered as martyrs and heroes of the French Resistance.

Other Marxists in Post-War France

French Marxists (though some do not really warrant the name) were among the first to outline the views which became known as “post-modernism”. These include the structuralist Louis Althusser (1918-1980), the cultural critic Guy Debord, and post-modern theorist Jean-François Lyotard. Pierre Bourdieu, the most eminent of recent French Marxists, died in 2001.

The French Marxist and Nobel-prize-winning microbiologist Jacques Monod (1910-1976) was one of the first to raise problems of ethics in Marxism in the post-1960s period.

French Marxists contributed to the development of Marx's ideas in the domain of cognitive psychology, and made contacts with Soviet scientists such as Luria and Leontyev. See:

- Georges Politzer's Critique of the Foundations of Psychology (1928);

- The work of Henri Wallon (1879-1962);

- Lucian Sève's Man in Marxist Theory (1968);

French Philosophy

French philosophy has continued to be a vital current of radical ideas. It's principal figures in the twentieth century were:

- The French-Swiss structural linguist Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) who has been so influential in 20th century French philosophy;

- The sociologist Emile Durkheim (1858-1917) is the main non-Marxist source for modern sociology;

- The structural anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss (b. 1908) regarded himself as a Marxist;

- The Russian/French interpreter of Hegel Alexander Kojève (1902-1968) first introduced the idea of a “struggle for recognition”, and the Hegelian psychologist Jean Hyppolite founded “French Hegelianism”, one of the fore-runners of postmodern theory;

- The Phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961), Existentialist and radical critic of Marxism Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980), founder of modern women's movement Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986), the first theorist of the National Liberation Movement, the French-Algerian Frantz Fanon, were all strongly influenced by Marxist ideas;

- The psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan (1901-1981), literary critic Roland Barthes (1915-1980), post-structuralist Michel Foucault (1926-1984), postmodern Hegelian philosopher Jacques Derrida (b. 1930) represent a dominant anti-Marxist stream of French philosophy.

The writings of other French Marxists, not here available in English, may be found in the French Section of the M.I.A..